Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Katrina d’Autremont (CM 2011) and Jamey Stillings (CM 2012)

Photolucida is a Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to providing platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the national and international photography community. Critical Mass, Photolucida’s annual online program, is designed to foster meaningful connections in the photography world. Open to photographers at all levels, anywhere in the world, participants submit a portfolio of 10 images. Following an initial pre-screening, 200 finalists are selected to have their work reviewed and voted on by up to 200 distinguished international photography professionals. From this process, the Top 50 are chosen, and a range of awards is presented. Submissions open each June.

In 2025, we celebrate the twentieth year of announcing the Critical Mass Top 50 finalists! We are honored to partner with Lenscratch to reflect on this history through a special series highlighting two artists from two different years in each post. Each featured artist offers a window into the diversity of projects and voices that make up Critical Mass—from documentary and narrative photography to conceptual, photo-based practices. These Q&As share the history, intention, and trajectory of the artists, pairing their Critical Mass portfolios with newer work.

For Critical Mass 2025, we received submissions from artists across 26 countries, tackling subjects in countless styles—from black-and-white and digital photography to chemigrams, cyanotypes, photographic sculpture, and textiles. Our esteemed jurors, representing a wide range of global perspectives, dedicate their expertise and thoughtful consideration to this process, often leaving feedback and encouragement for the artists.

Critical Mass continues to elevate emerging photographers, providing a platform that amplifies their voices to broader audiences and to the industry professionals who help shape careers. We are deeply grateful to everyone who makes this possible.

Katrina d’Autremont 2011

In Si Dios Quiere, photographer Katrina d’Autremont turns her lens toward the intimate spaces of her family history, exploring how memory, place, and generational ties shape our understanding of belonging. A 2011 Critical Mass Top 50 selection, the series unfolds within her mother’s childhood apartment in Argentina—a space layered with personal memory and cultural identity. d’Autremont’s work moves between closeness and distance, familiarity and estrangement, capturing the ways family can both anchor and unsettle us. In this conversation, she reflects on the origins of Si Dios Quiere, her ongoing exploration of family and landscape in The Other Mountain, and the role Critical Mass played in shaping her path as an artist.

Katrina d’Autremont is a fine art and lifestyle photographer based in Montana and Arizona.

Her work has received various awards including the PDN 30, the Silver Eye Fellowship for Photography, and Photolucida’s Critical Mass. Her work has been published in Real Simple, the American Photography 25, Ojo de Pez, and has been exhibited nationally and internationally.

She is often on the road traveling and photographing, most frequently in South America and the American West and is available for national and international assignments.

Instagram: @katrina_dautremont

Q: How did you first learn about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to submit your work?

KD: After graduate school I worked for a photography consultant, and I spent a lot of time researching competitions, grants, and events. At the time I had completed my series Si Dios Quiere, and when I learned about Critical Mass it felt like an ideal opportunity to share my work with a wider audience. So I applied.

Q: Your 2011 Critical Mass Top 50 series Si Dios Quiere explores how both physical proximity and emotional distance shape family relationships. How did photographing in your mother’s childhood home—layered with both memory and generational history—inform your understanding of closeness and separation?

KD: My mother is Argentine and my father is American, but I mostly grew up in the U.S. Every few years we would return to Argentina, and the apartment featured in Si Dios Quiere was always the place we stayed. It came to embody the idea of “home” in Argentina and connected me to that side of my family.

So many of my memories with cousins and grandparents are tied to that space. When I revisited it through photography, the apartment functioned almost like a stage and a character at once—holding both intimacy and distance.

At the same time, I felt a sense of “otherness.” I didn’t grow up in Argentina, and the apartment—with its old-world style—embodied that separation. It felt less like a current, modern space and more like a space of memory.

Q: In Si Dios Quiere, you describe family as a connective idea that extends beyond blood ties. How did your photographic process reveal the ways people become “family”—or resist that identity through distance, whether physical or emotional?

KD: I don’t know if the project answers that directly. What I showed was one family, but it serves as a stand-in for the broader idea of family. Everyone’s family looks different, but the layers of generations come through.

Family can be complicated—we may resemble one another, but nothing guarantees closeness. In some ways, it’s a choice. I think the images carry a psychological undercurrent: as a viewer you can’t always tell if there’s resistance or acceptance of the bonds of family.

Sometimes there are small visual cues of comfort—like when a subject is barefoot. That detail suggests ease both within the space and with each other.

Q: The title Si Dios Quiere conveys both hope and resignation. How did that duality—between acceptance and unpredictability—shape the mood, staging, or unplanned moments within the series?

KD: The title came after the images were made. It’s from a saying my mother and grandfather would repeat before bed: nos vemos mañana, si Dios quiere—“we’ll see each other tomorrow, God willing.”

I chose it because it carries both the intimate memory of that nightly routine and the idea that we don’t control everything about family—it holds an element of chance.

I don’t do much staging. My process is more about inviting people into a space, asking to photograph them, and letting things unfold naturally. Honestly, my family wasn’t always thrilled about being photographed—many people are uncomfortable in front of the camera. But because I was family, they were willing to go along with it, even if they didn’t fully understand what I was trying to do.

Q: Some photographs in the project feel carefully composed, while others unfold more spontaneously. How do you decide when to orchestrate a scene versus when to trust what emerges, and were there moments that surprised you and shifted the direction of the work?

KD: I mostly trust what emerges. I’m not the type of photographer who pre-visualizes or sets up elaborate compositions. Once I look through the lens, I see the composition in real time.

When I think about moments that shifted the work, I remember the photograph of my grandfather and his friend sitting on opposite ends of the sofa. Symbolically it suggests separation, but in reality it was a moment of connection. We were about to go out to dinner, which was something I often did with him—bringing along my great aunt Dorita or our family friend Marie Esther. Looking back now, especially as I watch my own parents age, I think of those dinners with 80-year-olds when I was in my twenties as a very special form of connection.

Q: In The Other Mountain, you juxtapose intimate family interiors with sweeping landscapes. How do you see the tension between domestic space and vast natural landscapes shaping the emotional tone of that series?

KD: I’m drawn to intimacy whether indoors or outdoors. I spend as much time as I can in nature, and even in wide open spaces, there’s a kind of intimacy.

The Other Mountain is less about domestic interiors, but I’ve always loved photographing interior spaces shaped by daily life. They hold a layering of detail that I could never stage myself.

Q: Many of the images carry a quiet stillness yet also suggest an undercurrent of absence. How do you approach photographing what isn’t there—the unseen histories and silences woven into your family’s story?

KD: I’m not sure I approach it directly. The absence is more implied, caught in symbolism rather than filled in.

People can act as stand-ins for others, and certain moments can echo other times. Often I photograph whatever strikes me, but it’s in the editing that the story and tone emerge.

I remember after my grandfather passed away, my family looked through a small book I had made of Si Dios Quiere. Everyone realized then that the space would never be the same without him. Looking back at those images now, I feel both presence and loss. Photography, for me, is often an attempt to hold onto fleeting moments.

Q: Your work often blurs the line between personal memory and broader cultural narrative. In what ways does The Other Mountain reflect not only your family’s experience but also larger ideas of belonging and displacement?

KD: Just as we choose how to relate to our families, we also choose where we live. My parents moved to Montana after they married, hoping to settle into ranch life in a remote area. My mom had just left Argentina to start a new life with my father.

As an adult living in Philadelphia, I returned to Montana during the summers. The project began as a way of documenting that early period of my parents’ lives, but over time it became more about my own relationship to the landscape—and about the myth of the West compared to its lived reality.

Q: The series conveys a quiet, almost cinematic sense of staging while remaining grounded in documentary. How do you balance intuition with intentional construction when composing these images?

KD: Living in a remote part of Montana, intentionality often means simply making the effort to leave the ranch to photograph people. Once I’m behind the camera, though, the scenes tend to unfold on their own.

I don’t think of myself as a documentary photographer searching for “truth.” I’m more interested in storytelling. The people I photograph are real—friends, neighbors, family—but within the image they also become characters. I rely on the viewer to fill in the gaps.

I feel fortunate that people invite me into their lives and allow me to photograph these intimate spaces.

Q: Finally, what impact did being named a Critical Mass Top 50 artist have on your career—whether in terms of immediate opportunities or in shaping your longer-term path as an artist?

KD: It was an important moment of exposure early in my career. Being part of that group gave me visibility and, I’m sure, led to further opportunities by helping my work reach a wider audience.

Jamey Stillings (2012)

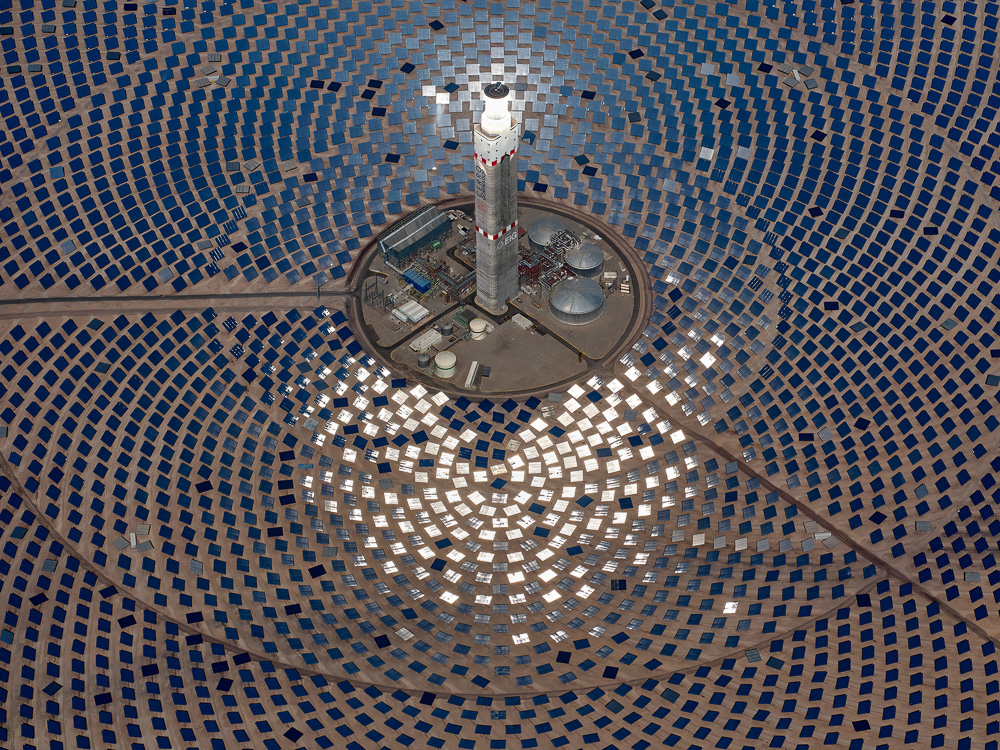

Jamey Stillings has spent more than a decade turning his camera skyward, documenting the vast intersections between human ambition and fragile landscapes. From the construction of the Hoover Dam Bridge to the sweeping solar fields of California’s Mojave Desert and Chile’s Atacama, his aerial photographs reveal the scale, beauty, and complexity of renewable energy development. Recognized as a Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50 artist, Stillings continues to explore how infrastructure reshapes land—and how photography can expand the conversation around our environmental future.

Born in 1955 in Oregon,Jamey Stillings incorporates documentary, artistic and commissioned projects in his photography. He has exhibited internationally and his work is held in the collections of the United States Library of Congress, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Nevada Museum of Art. With his book The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar (Steidl, 2015), Stillings won the International Photography Awards Professional Book Photographer of the Year in 2016.

Instagram: @jameystillingsphoto

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

JS: I attended my first Photolucida in 2011, where I shared work from The Bridge at Hoover Dam project. It was only my second chance to present work to such a diverse group of reviewers, and it was there that I first learned about Critical Mass. I saw it as a unique opportunity to place my work in front of a wide range of photo professionals—and it has indeed proven to be just that.

Q: Your CM 2012 Top 50 project, The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar, is such a fascinating series. Can you share the origins of this project? Did it begin as a personal exploration or a commissioned assignment?

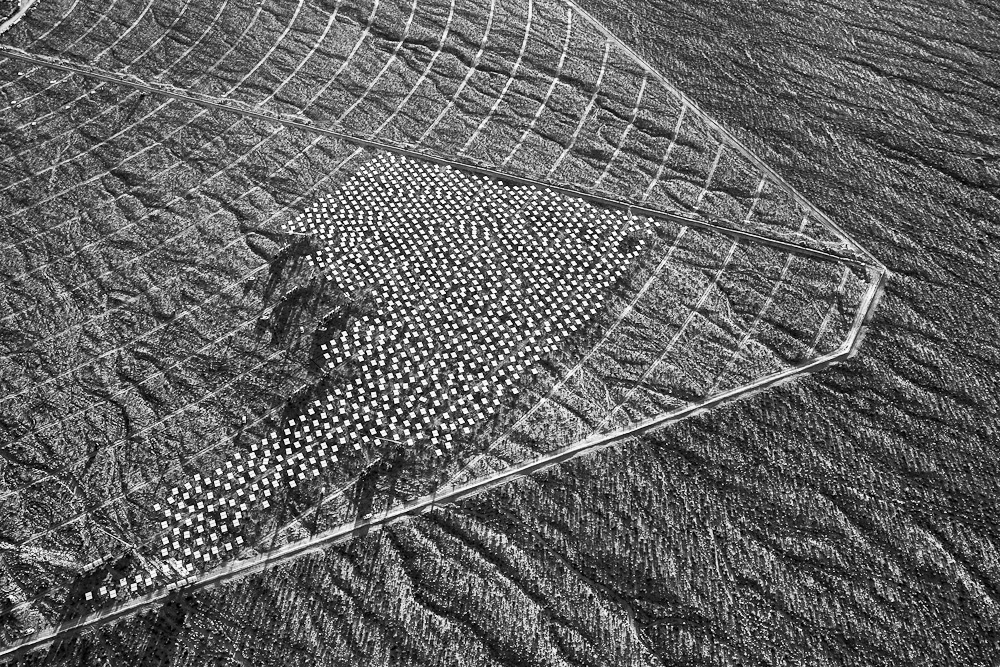

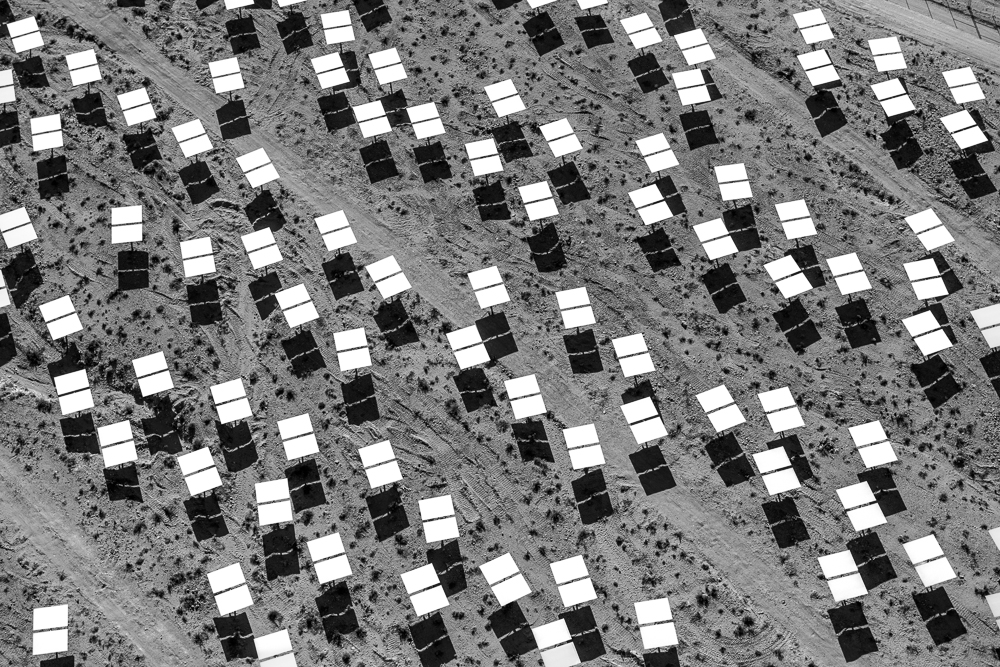

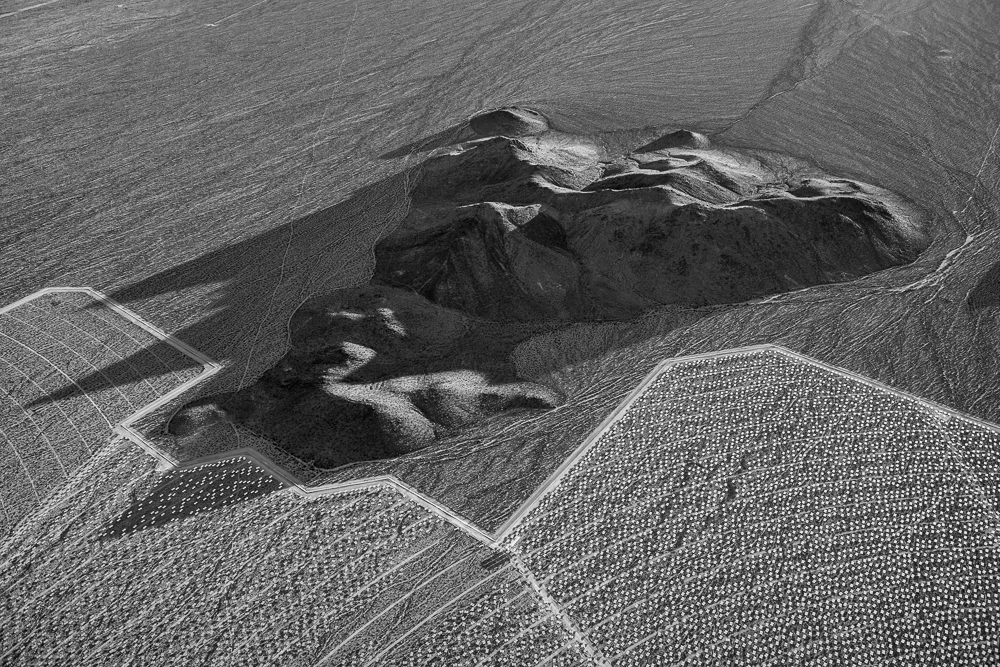

JS: It began as a personal project and, much like , it was a creative gamble. In 2010, as I was finishing the Bridge series, I started looking for new ideas that would merge my fascination with human-altered landscapes and my environmental concerns. Renewable energy had long been of interest to me, and several large-scale projects were underway in the American West. The most ambitious was the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in California’s Mojave Desert—the world’s largest concentrated solar thermal power plant at the time.

I sensed it would be a compelling project, combining groundbreaking renewable energy development with pressing questions about land and resource use. Between 2010 and 2014, I flew over Ivanpah nineteen times in a small helicopter. In 2015, Steidl published The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar, and the following year the book was honored with the International Photography Awards, including Professional Book Photographer of the Year.

Q: Much of your work explores human-altered landscapes. What in your background first sparked this interest and propelled you toward this theme?

JS: Honestly, I think it’s in my DNA. I’ve always been fascinated by the tension at the intersection of nature and human activity. As a species, we constantly reshape the environment to serve human needs—sometimes with foresight, often with only short-term utility in mind. Ivanpah allowed me to merge my aesthetic interests with my environmental concerns. Projects like this operate almost like land art on a monumental scale; from the air, they evoke the same sense of intrigue as ancient interventions like the Nazca Lines in Peru.

Q: With The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar, specifically, what were you hoping to accomplish by putting these images into the world? Do you find that all your projects share similar goals, or does each carry a unique intention?

JS: I once read that 90% of climate change–related imagery focuses on the problems, while only 10% highlights solutions. My goal is to dedicate my creative energy to documenting and amplifying efforts toward solutions. When Ivanpah was conceived, it was hailed as the “Hoover Dam” of its era. Although shifts in renewable energy technology and economics altered its trajectory, the project gave me a chance to document history in the making—from pre-construction to full power generation.

Over four years and nineteen flights, I came to know those fourteen square kilometers of desert intimately. The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar enabled me to fuse art and environmental storytelling, and the work was eventually published worldwide. Each of my projects is unique, yet all fall under the larger umbrella I call Changing Perspectives: Renewable Energy and the Shifting Human Landscape.

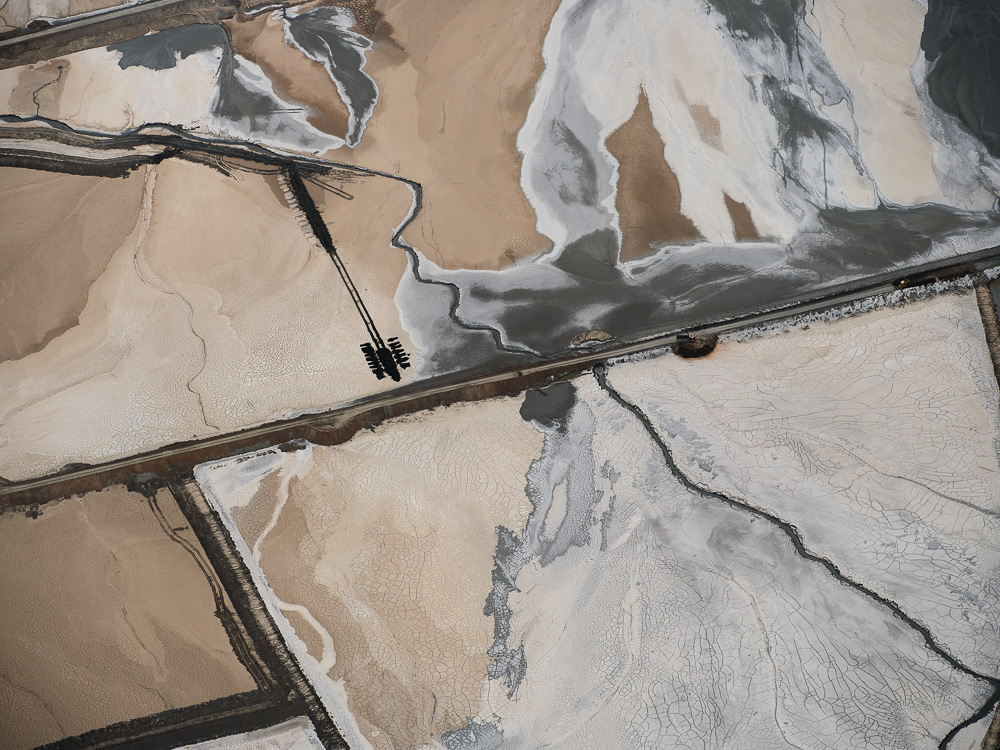

Q: You’ve also photographed renewable energy landscapes in Chile’s Atacama Desert. How did your interest in that region and its energy initiatives develop?

JS: After documenting renewable energy projects across the American West between 2010 and 2015, I wanted to expand Changing Perspectives into a global project. The Atacama Desert was an obvious next step. Not only is it one of the starkest and most visually striking landscapes on Earth, it’s also central to global energy and resource debates.

Chile produces one-third of the world’s copper and is the second-largest producer of lithium—both industries based largely in the Atacama. At the same time, the region holds some of the highest solar and wind potential on the planet. When renewable energy costs fell below fossil fuel production nearly a decade ago, mining operations became natural customers. That nexus—between renewable energy and resource extraction—was both visually and thematically compelling, and photographing the Atacama from the air was unforgettable.

Q: You’ve worked with helicopters, planes, and drones to capture aerial photographs. When did you start using drones, and how did that change your process compared to working from an aircraft?

JS: The majority of my work is still created from helicopters and airplanes, usually at altitudes between 1,000 and 5,000 feet. At those heights, drones simply aren’t practical without special permissions. Helicopters and planes also allow me to cover vast territory quickly.

That said, nothing compares to the fluidity of photographing from a helicopter. With the right pilot, it feels more like street photography in the sky—you can experiment, improvise, and respond to what unfolds. While I haven’t yet created what I consider “art” with drones, many of my colleagues are producing remarkable work. As technology improves and costs come down, I expect drones will play a greater role in my practice.

Q: Funding large-scale environmental projects can be a challenge. How do you typically finance your work, and what percentage of your projects are self-funded?

JS:For many years, my commercial photography funded my documentary and fine art projects. Between 2009 and 2016, this model allowed most of my projects to break even through book sales, licensing, and fine art prints. The Atacama project, however, required significant financial support from my commercial practice. Now, as I transition away from assignments to focus on long-term projects, the funding model has become more difficult. Breaking even is harder, but the drive to keep pursuing this work remains strong.

Q: Would you describe yourself primarily as a fine art photographer or a commercial photographer? Why?

JS: I’m simply a photographer—an artist. My foundation is in fine art and documentary photography, with a BA in Art/Art History from Willamette University and an MFA in Photography from RIT. Commercial work sustained me for decades and supported my personal projects, but the turning point came during the Great Recession, when I began the Bridge project in 2009. Since then, my focus has shifted toward long-term projects that align with my vision. While I wouldn’t turn down a compelling commercial assignment, my priority now is devoting my creative energy fully to personal work.

Q: Do you have a sense of the impact your images have had on environmental discourse or public conversations about renewable energy and land use?

JS: It’s difficult to measure impact directly. Over the past fifteen years, my work has been widely published and exhibited, and I’ve had the privilege of presenting at TEDx and TED Countdown, universities, museums, and festivals. I see myself as one voice in a larger conversation—part of a matrix of artists, activists, and scientists raising awareness and inspiring change. My hope is simply that the work contributes to the willpower we need, individually and collectively, to create a livable future.

Q: Finally, did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist open any new opportunities for you—either immediately afterward or in the long run?

JS: Absolutely. I’ve always valued Critical Mass as an accessible and vital way to share my work with a broad community of jurors, peers, and colleagues. While I can’t point to one specific opportunity that came directly from being in the Top 50, the visibility it provided has been invaluable.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Amy Friend (2019) and Andrew Feiler (2020)September 29th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Jennifer McClure (2017) and JP Terlizzi (2018)September 28th, 2025