Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz Cohen

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Mehrdad Mirzaie and Liz Cohen are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

This conversation took place in the summer of 2025 and centers on Liz Cohen’s intertwined roles as an artist and educator. The discussion unfolds in two parts: the first focuses on Cohen’s artistic practice, exploring how she constructs long-term, durational projects that move between photography, performance, fabrication, and social engagement — and the second, a closer look at her pedagogy, which mirrors her studio work in its embrace of complexity, contradiction, and radical individuality. The text begins with a short essay introducing the contexts and ideas that shape Cohen’s work before moving into a conversation that traces the connections between her artmaking and teaching.

When Liz Cohen speaks about Phoenix, it becomes clear how deeply her environment influences her practice. She describes the city as “vast, disjointed, and under the radar,” a place with fewer rules and less pedigree, defined by its contradictions — desert and highways, transplants and shifting identities. For her, this isn’t just a backdrop but a strategic vantage point: a space where she can engage expansively with the politics of land, movement, and identity from a distinctly Southwestern perspective. It’s personal — she grew up here — and being in Phoenix allows her to reflect on the past while creating work rooted in the landscapes that formed her. Listening to her, one realizes she is not simply fabricating ideas in the studio; she is living what she is creating. This way of inhabiting a place becomes an important window into her work — evidence of the precise vision she brings to shaping the complexities that run through her discourse and artistic practice.

Cohen’s work operates at the intersection of artistic practice and pedagogy — two realms that are deeply intertwined in her career. As a multidisciplinary artist and educator, she has spent decades navigating themes of identity, performance, representation, labor, and cultural archetypes. Her projects move fluidly between personal narrative and broader social systems, whether transforming herself into a car builder and bikini model, abstracting poetic narratives, or engaging with histories and subcultures through automotive and performative installations. Across her body of work, she consistently challenges fixed notions of gender, culture, history, and power, creating space for nuance, fluidity, and agency. Central to her method is the use of the “thought experiment,” not as a purely theoretical device but as a lived, embodied inquiry — testing the limits of identity, technology, and history through durational, often physically demanding processes. Many of her works unfold over years, dissolving the boundary between artmaking, relationship-building, and cultural immersion.

Her own background — a Spanish-speaking childhood in Phoenix shaped by Colombian and Syrian Jewish influences — infuses her work with an intuitive understanding of fluidity, contradiction, and the labor of coherence within complexity. She examines systems that categorize or exclude while also finding ways to occupy spaces that might initially seem closed. This pursuit of belonging without erasure runs through her projects, from the Trabantimino — a mash-up of an East German Trabant and an American El Camino — to GAZ COFFEE, a Soviet military vehicle transformed into a platform for hospitality and dialogue.

Cohen’s pedagogy mirrors her artistic practice in its resistance to fixed meanings and its embrace of complexity, contradiction, and radical individuality. She cultivates what she calls an “uninhibited, experimental” classroom — spaces where students have the “freedom to change their minds, freedom to provoke, freedom to feel deeply,” and to pursue work that is fluid rather than static. For her, critique is not about judgment but about “peeling back layers,” asking questions, holding each other accountable, and identifying threads to explore. She encourages students to “question everything,” especially reductive cultural narratives and virtue signaling, making space for nuance and what she describes as “thoughtful audacity.”

In guiding students to develop their artistic personas, Cohen frames identity as a kind of mythology — “what kind of vessel are you forging for others to live vicariously through” — balancing visceral and conceptual approaches. She sees radical individuality not as isolation but as “a precursor for authentic group membership,” an approach that fosters both freedom and collective belonging. This philosophy challenges her students to think expansively about their own work and to understand artmaking as a process of engaging with shifting meanings, layered histories, and the politics of representation.

MM: I’d like to start by thanking you for this conversation and for sharing your time with me. I’d also like to open with a quote from your project Body/Magic:

“There is a distance between how I saw myself in 2002 and how I saw myself in 2020. There is a distance between how I see myself and how others see me. I cannot gauge the distance. I think a lot about aging.”

Would you please tell me more about this idea of “distance”?

LC: The way I view belonging and critique has changed over time. From 2002 to 2008, I was deeply immersed in building the Trabantimino. I was doing very little teaching. I was trying to prove that breaking into what appeared to be closed systems was possible. I was committed to radical individuality and freakiness as a path to belonging – the idea that remaining true to oneself is integral to genuine group membership. This condition does not have to be a paradox. I worked tirelessly at fabrication and visiting lowrider shows. Ultimately, I became a fringe member of a culture I deeply admire. During that process, I was adamant that the work was not a critique of shop spaces or car culture. I was conducting a thought experiment concerning the possibility of belonging. There are many ways to share experience and find connections. I am allergic to the idea that there is a playbook.

I didn’t expect the outcome of the Trabantimino to be optimistic, but ultimately it is. The work is about finding a way in. I started asking friends if they had ever encountered someone with a lot to offer, experiencing deep rejection. That led me to a poet, Eric, who self-described as a eunuch.Eric had written poetry that had brought him into circles with Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. They had taught writing in schools and in prison. They had also run for a local governmental position. Their relationship to gender was the catalyst for dismissal from his teaching jobs and sensational reporting during a run for office.

The work with Eric led me back to Dazza del Rio, whom I had met in Fresno in 2003 at a Lowrider show. She is an icon who modeled alongside cars and appeared as a covergirl and in the magazines. We are both around the same age, and when I reached out, she hadn’t done any lowrider shows or modeling in over a decade. We were both going through the transition to menopause. My body has been young, pregnant, birthed, and gone through menopause.

MM: How do you see yourself now—as an artist and educator—compared to when you first began your career?

Halfway through the Trabantimino project, I started teaching full time as Artist-in-Residence/Head of Photography at Cranbrook Academy of Art. It was exciting to teach at an institution that provided so much freedom and trust to artist mentors and students. Every discipline was led by one mentor who acted as a guide to fifteen students. Each of the Artists-in-Residence provided their own pedagogical model. I developed a program steeped in field, literary, and studio research. Each student was responsible for designing a research process appropriate to their ambitions. As a group, we embarked on the branches of research together, taking field trips every week, sharing readings, and discussing artistic output. The hope was that each student artist could practice a radical self-expression that reflected being in the world.

©Liz Cohen, Beatriz Cohen, and Rafi Cohen-Foltyn at the Him exhibition at the Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, 2015 Credit: Brian FoltynLiz Cohen, Beatriz Cohen, and Rafi Cohen-Foltyn at the Him exhibition at the Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, 2015 Credit: Brian Foltyn

After ten years of working in the small, cloistered environment at Cranbrook, I came to ASU – which is almost the opposite. At ASU, I teach both undergraduate and graduate students. Most of the people I have the opportunity to interact with are studying for their BFA in studio art. It’s a very dynamic environment. Most of my students work 30 hours a week in addition to their studies, which in many cases has them deeply immersed in more than one institution. They have a lot to say, and I hope to provide an art historical framework (from a practitioner’s perspective) and a platform for producing work that empowers each student. Many of the MFA students I work with at ASU are working at a high level. With them, my hope is to cultivate camaraderie and a framework for talking about art that is generative to their work. I toggle between intimate one-on-one studio discussions and group situations where I provide prompts for framing our discussions around each other’s work.

MM: Some context about your early life would be very helpful—could you share more about your family and where you come from? How do you see your background as essential to the work you make?

LC: I grew up in Phoenix in a Spanish-speaking home shaped by my parents’ layered identities (inherited and chosen): Colombian, Syrian Jewish, Catholic, secular, immigrant. My father grew up in an Orthodox Jewish household listening to his parents speak Arabic. My mother grew up on the Caribbean Colombian coast in a loosely Catholic environment. My parents’ relationship embodied a defiance of sectarian boundaries. That defiance shaped me. I grew up navigating multiple linguistic, cultural, and spiritual systems that did not always align. The discomfort and joy experienced in the in-between is fundamental to my practice.

MM: In what ways do these inherited complexities show up in your artistic decisions, whether consciously or unconsciously?

LC: In my work, I often examine systems that categorize or exclude based on national borders, gender roles, or aesthetic hierarchies.

MM: Please share a bit about your own educational trajectory? Do you see a connection between your academic path and your current position as both a contemporary artist and a university professor?

LC: I am fortunate to have studied with people who modeled lives built around the commitment to producing art and education. Bill Burke and Larry Sultan were foundational figures for me – not just as artists, but as mentors whose teaching was itself a practice. Stephen Goldstine, who directed the MFA program I attended, was also a significant influence: a great intellect, generous, deeply invested in people and inquiry. They shaped me. There were also tremendous gaps. There was no roadmap for me to face the challenges young women face when they leave their lives as students. There is a kind of invisibility that I think is common to feel after graduate school. For my generation, I think that was magnified for young women. I had to find my way. That experience has marked my professional life. My work as an artist and professor is deeply intertwined – in both areas, I try to create spaces of agency and freedom within and without subjugation.

MM: You’ve lived and worked in many cities, and now you’re based in Phoenix. How has working in those places influenced your practice—and how do you feel about working in Phoenix today?

LC: Everywhere I’ve lived has complicated, sharpened, and expanded my relationship to ideas, material, and process. San Francisco is a dense urban environment with rich street culture, activism, and artist-run communities. The connection between art, politics, and community was palpable. Detroit gave me a sense of materiality, intentional community, and creative survival. It taught me to think about labor, industry, and resilience in very real terms.

Phoenix is different. It is vast, disjointed, and under the radar. There is a kind of freedom in that there are fewer rules and less pedigree. It’s a city of transplants and contradictions – desert and highways.

MM: “They taught me about performance,” you told Hyperallergic.

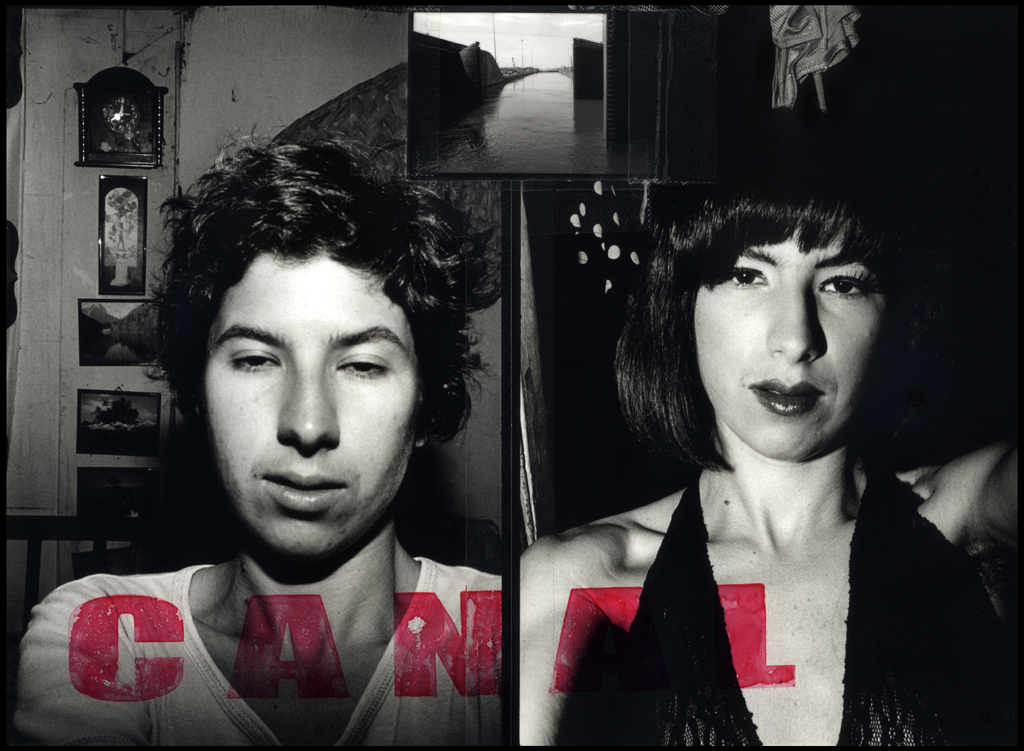

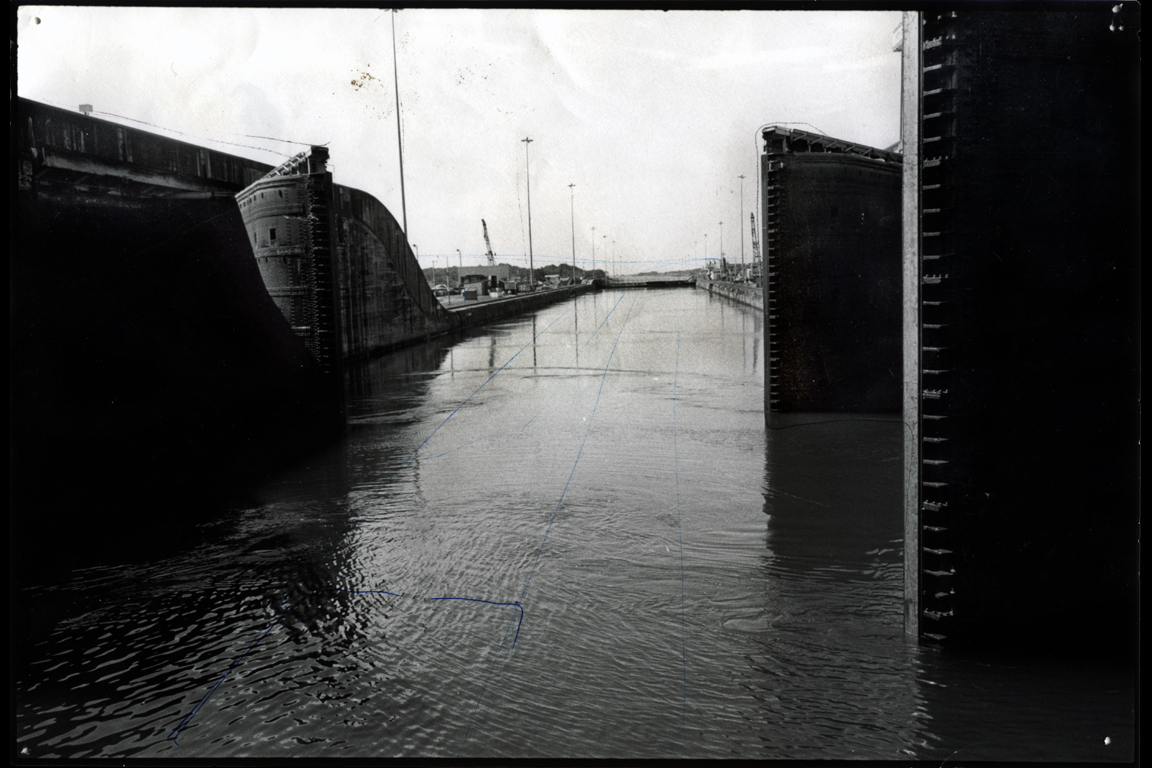

I’d like to focus on the Canal project. This was a four-year street photography series, but evolved into something much more participatory and performative.. How did that transition happen, and how did Canal influence the performative elements that became central to your later works?

LC: CANAL began with street photography, but organically, it became much more. Linette, whom I had photographed extensively, proposed to dress me up and invited me to stand on the street with her dressed as she does rather than with my camera. The intensity of the experience opened up new avenues for me. My work became immersive and reciprocal. My body’s presence in the work was important. I was functioning as part witness, part subject, part participant.

MM: Each of your projects since then reflects performance in different and extraordinary ways—how do you see that connection unfolding across your practice?

LC: Performance gave me a way to use my body to collapse the distance between artist, laborer, object, and image. It allowed me to simultaneously be analytic and exercise shared agency over archetypal images of woman, labor, and cultures.

CANAL led me to understand that through deep immersion.

Installation view of work from CANAL in Liz Cohen: La Avenida de los Mártires at Diablo Rosso, Panama City, Panama, 2024, Credit: Raphael Salazar

MM: About the car: in your project description, you wrote, “A series of events led me to purchase an East German Trabant in Berlin in 2002.” Can you tell me more about that sequence of events? What led you down that path? What were the personal or political motivations at that moment?

LC: I was in Germany in 2002 for a residency with Akademie Schloss Solitude. I became fascinated with the Trabant which was in the process of becoming a Cold War relic. It was a failed utopian object. Fabricating a mash-up between an East German Trabant and an American El Camino, another failed utopian object, seemed like a good way to bring history, fantasy, labor, and identity into friction.

Buying the Trabant was not impulsive – it was symbolic. The Trabant stood in for displaced people, failed ideologies, and my attempt to reconcile seemingly contradictory parts of myself.

MM: You’ve called both the Trabant and the El Camino “failed utopian vehicles.” What drew you to this idea of utopia through machinery—and how do you see it connected to identity?

LC: The Trabant and El Camino were both born from a beautiful optimism that ultimately cracked under the weight of their failures. As I see it, their histories are emblematic of scarcity, dysfunction, and abandonment.

The mash-up of the cars reflects the challenge of assimilation. Hybrid identities don’t fit into neat, dominant narratives. The friction between ideals, archetypes, and reality can generate barriers to fully realizing ourselves. This tension motivates my work. I’m interested in the poetry of malfunction leading to invention – a freedom to exist without needing to conform.

MM: I’m really interested in how you connect abstraction and reality in your practice. I’d love to talk about this in the context of the Him series. How do you navigate the space between poetic abstraction and lived experience in your work?

LC: Him came from a place of sadness. It’s about being thrown out when you have something to offer. It’s about loneliness and being unrecognizably different. Him is a portrait that never provides a likeness. I was struggling to avoid being reductive.

MM: Also, you move away from narrative-driven work toward something more atmospheric and open-ended. What motivated this shift toward abstraction and poetic form?

LC: Him is quieter and more open-ended than the previous work. It highlights the act of projection. The biography is cloaked, like Eric, the poet.

MM: When working across media—from weaving to collage to photography—what tells you that a certain idea or emotion needs to take a particular form?

LC: Photography for me is usually narrative. It grounds the work in reality – real people with real challenges. The textiles are a space for developing iconographies. History, ideology, and narrative sequence can collapse. Fabricated objects are artifacts.

MM: Several of your works, including ZWICKAU ROUTINE and GAZ COFFEE, touch on Soviet and Communist iconography. What draws you to those histories, and how does Soviet and Communist ideology appear in your practice?

LC: I was raised with an intense awareness of global politics. Growing up in the 80s, the Cold War was palpable. My parents were from Colombia, and the Cold War played out very differently there. I grew up observing clashes in ideologies and economic systems that lead to threatened and actual violence.

Living in the United States and traveling with my parents to Colombia, the Soviet Union, and China, I observed various aesthetics for communicating political narratives, aspiration, and power. I am interested in the ambition and hope delivered by Trotsky or Ford, and at the same time, I am aware of the gravity of their failures.

Mashing up iconographies functions to connect the past, present, and future across geographies.

MM: You draw unlikely connections—Soviet influence in Latin America, lowrider hydraulics and Cold War history. Do you see your practice as a form of counter-archiving or political archaeology?

LC: Yes, those descriptors could work in the sense that I look at what’s excluded, hidden, or flattened by dominant narratives. I grew up navigating seemingly contradictory identities – secular, atheist, Jewish, Latina, Spanish-speaking, with the last name Cohen. The stories projected onto me never quite fit. That distance between how I see myself and how others see me was often unsettling. I’ve spent a lot of my time trying to understand that tension.

I’m interested in the gap between categories. That interest leads me to the connections between Cold War ideologies and Latin American resistance movements and the connections between East German engineering and Lowrider culture. I’m building meaning out of these complicated intersections.

The connections aren’t random. I am responding to the urge to belong without erasure. I sift through objects, images, and ideologies to propose counter-narratives that challenge exclusion and offer space for those who don’t or can’t conform.

MM: You once said, “I just realized that World War II is a landmark moment in the history of lowriding.” How do you think about World War II in your work? What kinds of forgotten histories are important to you, and where does that interest come from?

LA: World War II created a rupture – a before and an after. The end of the war brought tremendous change to the landscape of global power, migrations, racial hierarchies, and aesthetics. Lowrider technologies have deep roots in World War II and its aftermath. Mechanics learned about hydraulics while working on war planes. For Latinx Americans there were new avenues and barriers to belonging and class mobility.

I come from a background of various diasporas. I am interested in how ideologies, culture, and objects travel across geographies and how their meanings change. The World Wars and the Cold War are not distant histories. They are ongoing conditions.

MM: With GAZ COFFEE, you’re again working with vehicles—but now creating spaces for social interaction. What inspired this move from performance to hospitality, from transformation of self to transformation of public space?

LC: GAZ COFFEE emerged from a desire to shift the focus from the labor of belonging and the urban workplace to the shared labor of the field and the family. All labor is, in essence, a service, but as I’ve moved through communities, the distance between labor and consumer has grown. Sex workers touch their clients. A coffee farmer will not meet most of the people who drink their coffee. I’m interested in bridging the distance.

GAZ COFFEE is still a performance, but the emphasis is on hosting, creating opportunities for unexpected encounters, and generating solidarity. The GAZ COFFEE vehicle is a modified 1968 Soviet Gaz 69A. The GAZ is equipped to serve coffee. It is an ambulant platform for hospitality and dialogue.

The project has also been a way to think about returning to Colombia, literally and imaginatively.

Installation view of work from BODY MAGIC in There Are Other Skies at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, Arizona, 2025, Credit: Claire A. Warden

MM: In other interviews, You describe your artworks as “thought experiments” shaped by analytic philosophy. How do you balance that intellectual structure with the emotional or bodily dimensions of your practice?

LC: Art is a safe place for dangerous ideas. It is a place for generative ideas. An artwork is a proposition. What if we saw the world like this? What if the story were framed like this? What if this kind of behavior or style were celebrated rather than demonized? I guess it is a space to play out anxieties. The hope is that the thoughts lead us somewhere else.

MM: Your work often engages with “otherness.” You’ve created several series that focus on the lives and identities of others, yet the storytelling always feels deeply personal. How do you define your relationship to your subjects? What responsibilities or tensions do you navigate when representing someone else’s experience through your art?

LC: I’m drawn to radical individuals who are fearless, dignified, and full of contradictions. They refuse to shrink. They are usually exhibitionists. I would rather photograph people who want to be seen and insist on being seen fully. Their pain or deviance does not inhibit them.

I primarily work on long-form projects. The process unfolds over time, and I build genuine relationships. There has to be trust. Everyone involved is taking the risk of being misunderstood on record.

There is always going to be some level of tension. My goal isn’t to speak for someone. I can’t see someone the way they see themselves. I hope that the distance in perception isn’t too vast and that the process of depiction is generative. I hope the image is a layered space where our identities coexist and offer something else.

Installation view of work from Conchita’s Secret in Flow States – LA TRIENAL 2024 at El Museo del Barrio, New York. Photograph by Matthew Sherman/Courtesy of El Museo del Barrio, New York.

MM: What drew you to teaching, and how do you see your role as an educator in relation to your practice as an artist?

LC: My mom was a teacher, and my mentors were teachers. I saw them as people who viewed teaching as a generative and political act. I like to think of education as a space of empowerment rather than policing, where fluidity and dissent are welcomed, not shut down. Art education doesn’t work very well when students feel inhibited.

I try to approach teaching the way I approach making art—proceeding with propositions rather than judgments. I hope to create a space where my students and I can resist fixed ideas. Teaching and my practice are in sync when they succeed in creating spaces of critical freedom—spaces for thought experiments. Teaching and making art are both part of the same impulse: to imagine new ways of being together.

MM: How do you encourage your students to embrace complexity and contradiction in their work, especially when their identities don’t easily fit dominant art world narratives?

LC: It’s important to identify when a story is disingenuous or reductive. The self is a good place to start: How do we belong? Who do we feel affinity with? How can we make space for more? And make space for history and idiosyncratic layering.

MM: How do you sustain your practice in environments that may not always be supportive of identity-based work?

LC: Keep working!

I can’t change who I am or the challenges that come with it. I did not set out to make identity-based work, but the story I have to tell has fit that political narrative. I believe it can fit into others as well. Again, it’s about not being reductive—figuring out how things can fit rather than rejecting them.

MM: Your work often challenges fixed cultural notions and archetypes. How do you explore these ideas in your artistic practice?

LC: Time – I don’t decide what things mean. Time allows me to see what other people think it means and to react to that. To react to changing cultural moments.

MM: Is there space in your philosophical framework for shifting or unstable meaning? How does that affect how you make and teach art?

LC: Definitely. I would be worried if there weren’t space for that. We are receiving information that is new to us all the time. We need space to react to it. We need space to ask the what ifs. To make propositions. To think through things together. The paradox of radical individuality as a precursor for authentic group membership.

Installation view of work from the BODY MAGIC series in Transfeminisms at Mimosa House, London, England, 2024, Credit: Josef Konczak

MM: Across your various series, there seems to be a thread of optimism or hope in how you tell stories—especially those centered on others. How do you see the role of hope in your work?

LC: I want to be optimistic. I choose people that are fascinating to me – fearless, authentic, exhibitionist. I am also suspicious of optimism. People experience darkness and rejection. I just don’t want to be the person that delivers that. If my work is a proposition, the proposition might be what would the world look like if we thought of this person or these behaviors like this.

MM: Please tell me a little about engaging students in conversations about fixed cultural narratives and assumptions? What role should students play in challenging or responding to these ideas in the classroom?

LC: Ideally art provides a space for questioning everything. It is very important right now with the culture of signaling. What is transactional? What is virtuous? Is there another way to think? Making space for nuance. Thoughtful audacity. Space for stories that aren’t soundbites. Virtue signals and soundbites can be dangerous. They might not be good for the process of making art.

Liz Cohen (United States, 1973) is a photographer, performance artist, and object maker whose decades-long career focuses largely on the intersection of immigration, industry, labor, and women’s representation in popular media.

Cohen is perhaps best known for her BODYWORK project, in which she simultaneously transformed an East German Trabant into an American El Camino lowrider while inhabiting a new identity herself as a car customizer and bikini model. Through this immersive series, Cohen produced a body of work that challenges American cultural norms as they pertain to the eroticization of the automobile industry as well as the challenging role of women’s bodies in that space. Cohen’s series, BODY MAGIC (2020), sees the artist further explore similar themes. In black and white photographs, Cohen poses with the iconic lowrider model Dazza del Rio in images that refer to Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of the bodybuilder Lisa Lyon.

The artist’s work has been recently included in the survey exhibition, Flow States – LA TRIENAL 2024 at El Museo del Barrio, New York (NY), and the landmark exhibition, Xican-a.o.x. Body at the Perez Art Museum, Miami (FL) in 2024, both with an accompanying catalogue. In early 2021, Cohen was the subject of a survey retrospective, Body/Magic, at the Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe (AZ)

Recent group exhibitions include transfeminisms at Mimosa House, London (UK) in 2024; Desert Rider: Dreaming in Motion at Denver Art Museum, Denver (CO) in 2023; Stories of Abstraction: Contemporary Latin American Art in the Global Context at the Phoenix Art Museum (AZ) in 2020; and Shapeshifters: Transformations in Contemporary Art at the Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills (MI) in 2020.

In 2020, Cohen received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Past awards also include the Fountainhead Residency (2024), Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Biennial Award (2019); the Creative Capital Foundation Project Grant (2005), and a MacDowell Colony Fellowship (2001).

Liz Cohen lives and works in Phoenix, AZ.

Cohen’s work is interdisciplinary, bringing together inquiry in women’s studies, literature, poetry, and auto mechanics as well as expertise in documentary photography, performance, video, installation, and sculpture.

Instagram: @lizcohenstudio

Mehrdad Mirzaie is an Iranian multidisciplinary artist, curator, and educator currently based in Phoenix, Arizona. His practice centers on the afterlives of images, the politics of memory, and historical Image, particularly in regions marked by censorship, state violence, and historical erasure. Working primarily with photography, archives, and alternative image-making processes, he explores how visual histories are preserved, reinterpreted, or lost, emphasizing the interplay between bygone eras and contemporary contexts.

Mirzaie’s research extends to the history and philosophy of photography, where he examines the role of images as conduits for historical narratives and storytelling. He is serving as a curatorial assistant and collection assistant at Northlight Gallery, where he continues to deepen his curatorial and research experience. He received his MFA in Photography from Arizona State University in 2025 and is currently pursuing an MA in Art History at ASU, with a focus on image-based art in Iran and the broader Global South.

He is also the founder of the Tasvir Archive Project (established in December 2022), a research initiative focused on the history of Iranian image-based art and the archiving of photographic practices in Iran.

Instagram: @mrdadmirzaie

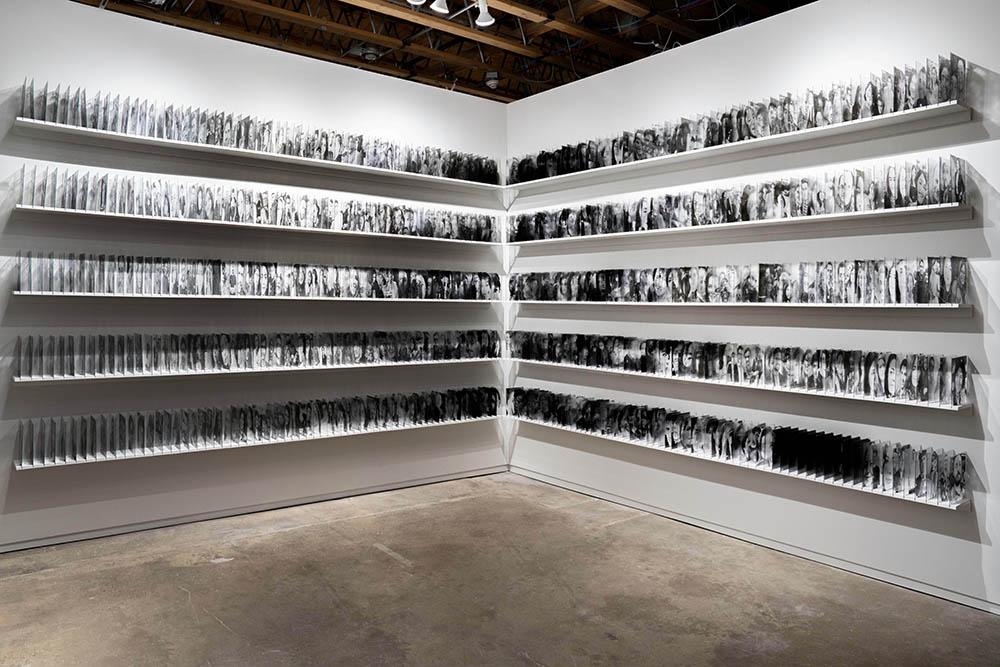

©Mehrdad Mirzaie, Room No.2: Archive Room,1000 Transferred Images on Glass, From Garden Series, 2025

©Mehrdad Mirzaie, Room No.2: Archive Room,1000 Transferred Images on Glass, From Garden Series, 2025

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025