Astrophotography: Molly Wakeling

©Molly Wakeling, Wakeling, 2017 : High dynamic range image of the Sun’s corona during the August 2017 solar eclipse, from Casper, Wyoming.

Molly Wakeling’s astrophotography ranges from peaceful nightscapes to the drama of lunar and solar eclipses, to exquisite images of deep space objects not seen with the naked eye. Her images capture the awe and wonder in the universe in which we all live.

Wakeling got into astrophotography in July 2015 after receiving her first telescope as a gift. Much trial and error later, she now has five astrophotography rigs set up in her backyard in Albuquerque, NM, including one dedicated to variable star observations. She is a Contributing Editor at Astronomy Magazine, writing the monthly “Observing Basics” column, as well as a member of the Board of Directors for the American Association of Variable Star Observers.Wakeling is actively involved in STEM outreach, sharing views through the telescope and presenting to astronomy clubs, classrooms, and star parties across the country, both in-person and online. She is also a host and broadcaster on “The Astro Imaging Channel” YouTube show.Wakeling recently earned her PhD in Nuclear Engineering.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/astronomolly_images

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/astronomolly

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@astronomolly_images

Gallery: https://app.astrobin.com/u/mollycule#gallery

An interview with the artist follows.

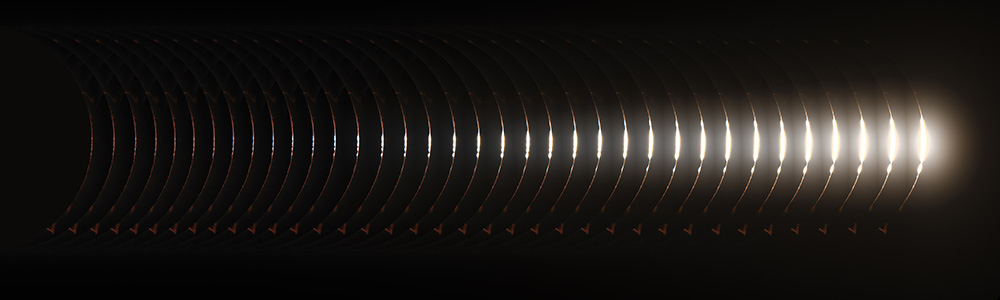

©Molly Wakeling, The Sun reappearing from behind the Moon during the April 2024 lunar eclipse, showing a phenomenon called Bailey’s Beads.

Statement

For over a decade, I have been exploring the cosmos through astrophotography, fueled by a lifelong fascination with astronomy. My work captures the breathtaking beauty of nebulae, galaxies, planets, comets, and more, revealing the universe’s vastness and wonder. What began with an unforgettable glimpse of Saturn through my first telescope quickly evolved into a passionate pursuit, and then an obsession. I strive to share the awe I feel when capturing these celestial objects, proving that the wonders of the universe are accessible and not confined to the realm of professional observatories. With patience, dedication, and comparatively humble equipment, I bring these distant galaxies and swirling nebulae into focus, hoping to inspire a sense of connection to something larger than ourselves and a renewed appreciation for the universe we inhabit. I want people to see what’s out there and feel the immense scale of the universe compared to our tiny world.

Marsha Wilcox: Tell us about your photographic journey.

Molly Wakeling: When I was 8, I saved up my allowance and bought a Crayola 110 film camera. I was taking pictures of anything and everything. Later, I had a fully plastic manual-wind 35mm camera that my mom gave me. When I was in 7th grade, we got our first digital camera, a Kodak EasyShare point-and-shoot. I took a picture of our cat and you could see individual cat hairs – the resolution was mind-blowing. I went to town with that. I took one of my favorite pictures with it, a cherry blossom. I focused in on the blossom; the background was blurred. I have taken many cherry blossom photos since then on much nicer cameras, but none have been as good as this one from 7th grade with a cheap camera.

I had been able to use a DSLR when I was in ROTC in college. I saw how much better the image quality was.

You carried a camera with you all the time. What kinds of things did you photograph?

I started college with about 20,000 pictures – and had 80,000 before I graduated. I wouldn’t say I was dedicated to doing photography. I was recording things that I did. I also loved taking pictures in nature. I would go on a hike just to get pictures of like leaves and flowers and nice vistas. After college, I began to try to make artistic photographs to represent beautiful things in nature. I worked on depth of field so it wasn’t just a single flat image.

In 2015 I got my first telescope as a gift.

Had you done any night photography or Milky Way landscapes?

No. I always wanted a telescope. I’ve loved the sky as long as I can remember. Astronomy was my favorite science. Growing up I watched a lot of NOVA and read a lot of books about astronomy. I liked the feeling of the bigness when I imagined the universe and all the things going on in it.

In college, I majored in physics on the astrophysics track and was able to take a lot of astronomy classes. We learned the winter sky, the winter hexagon, and constellation lore. I had my first view of Jupiter through a large telescope at a star party. It was amazing.

I took my new telescope out to the state park with friends. We followed the directions in the manual. I focused on a bright object in the sky – it happened to be Saturn. I was bowled over at how beautiful it was – it didn’t look real. My next thought was, “How can I get a picture of this so I can post it on Facebook and show it to all my friends?” I got an attachment that let me connect the DSLR to the telescope and turn it into a 2,000mm camera lens. I took some single frames of Saturn that were shaky, but I got pictures and that was a beginning. I started to take longer exposures of nebulae and galaxies, then I learned to stack multiple images together to get a better final image.

My uncle gave me his old 11-inch telescope. I started taking much better pictures because I could track using longer exposures. I also added a guide scope, a second telescope with a second camera, to better track the sky and take even longer images. I got a dedicated monochrome astrophotography camera and filters. I was getting better at photographing deep sky objects. In 2017, I won 2nd place in an Astronomical League astrophotography contest for my image of the Rosette nebula using my DSLR on a telescope.

The same uncle sold me his Takahashi FSQ-106N, which is the Ferrari of telescopes. I had a backyard for the first time and learned how to automate astroimaging, which allowed me to control the telescope from inside; I could sit where it was warm and not get bitten by mosquitoes.

Soon, I was able to photograph through two telescopes at the same time. I upgraded the mount and added a third scope to the mix. I started to become involved with the American Association of Variable Star Observers, and one of the members gave me a scientific-grade astronomy camera. I contributed to citizen science taking variable star observations with an 8-inch telescope and the CCD camera.

Tell us about your astroimaging.

Astrophotography is mind-blowing. There are so many incredible things space you can photograph from equipment you can put in the back of your car. You don’t need the Hubble Space Telescope to take good images of objects in space. It feels more real when you know the person who is taking the pictures and have seen their telescope and have heard about their escapades out imaging at 2 o’clock in the morning.

I get a lot of joy and satisfaction when the final image comes out of the stacking process. I’m bowled over by what I managed to catch. There’s celestial dust in the background that I didn’t know was there, integrated flux nebula – the collective light of the galaxy reflecting off interstellar dust, which is so incredible.

There are still a lot of things for me to learn about processing astroimages -, and they require a lot of care. I enjoy taking an image from the initial output to the finished product with color and background dust – and things that I didn’t even know were there. You zoom in and see galaxies in the background– I have some images I took with my backyard telescope that have galaxies that are over a billion lightyears away. You can’t beat that.

Astrophotography is a beautiful blend of art and science. I’m a problem solver and a troubleshooter, and I love to make things work — and then to finally see the jaw dropping result from the process and feel incredible about the beautiful things you create.

In the first couple of years I’d spend four or five hours on a target (subject) mainly because I had to pack up all my gear and go out to the observatory and set it up. I’d have to tear it all down to go home. I could image two or three nights a month that way. But once I had a permanent backyard setup, it wasn’t such a rush to try and finish an image. I started making deeper (longer) images and doing narrowband imaging. I think my longest exposure is somewhere between 50 and 60 hours.

Now that I’m in New Mexico, I have five of my own telescopes set up in the backyard. I also have a telescope at a remote observatory in Texas. I recently acquired land in Arizona with a friend. We go out there a couple of times each year to observe and do astrophotography under dark skies.

Tell us about your audiences – what they see, and what you would like them to see in your work.

I like to take the unique position as somebody who does both the art and the science. I do astrophotography and as well as astronomy. I have a degree in physics, and in two degrees in nuclear engineering. All this helps me to describe what is going on in the image.

©Molly Wakeling M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, located 31 million lightyears behind the constellation Canes Venatici.

Take the Whirlpool galaxy, for example. There is the main part of galaxy and a little companion galaxy next door. It looks for all the world like M51 (the big galaxy) is swallowing up little NGC 5195. But that’s not what’s happening. The two have passed through each other a couple of times and will do so again. This galaxy pair is about 75,000 lightyears across and 30 million lightyears away. Incredible.

©Molly Wakeling, Nebula region NGC 6559, with the Lagoon Nebula right next door, in the constellation Sagittarius.

Can you define your photographic style?

For regular broadband RGB images, I like to have as true a representation of the color as possible. I use a combination of the scientific basis and astrophotographers’ consensus about what the color is.

Galaxies can be tricky because it’s tempting to enhance colors that might be artifacts or change the hue so that it covers a wider color range and looks more artistic. In reality, some galaxies come out very gray. I try to find the balance between having representative color and make an image that is interesting.

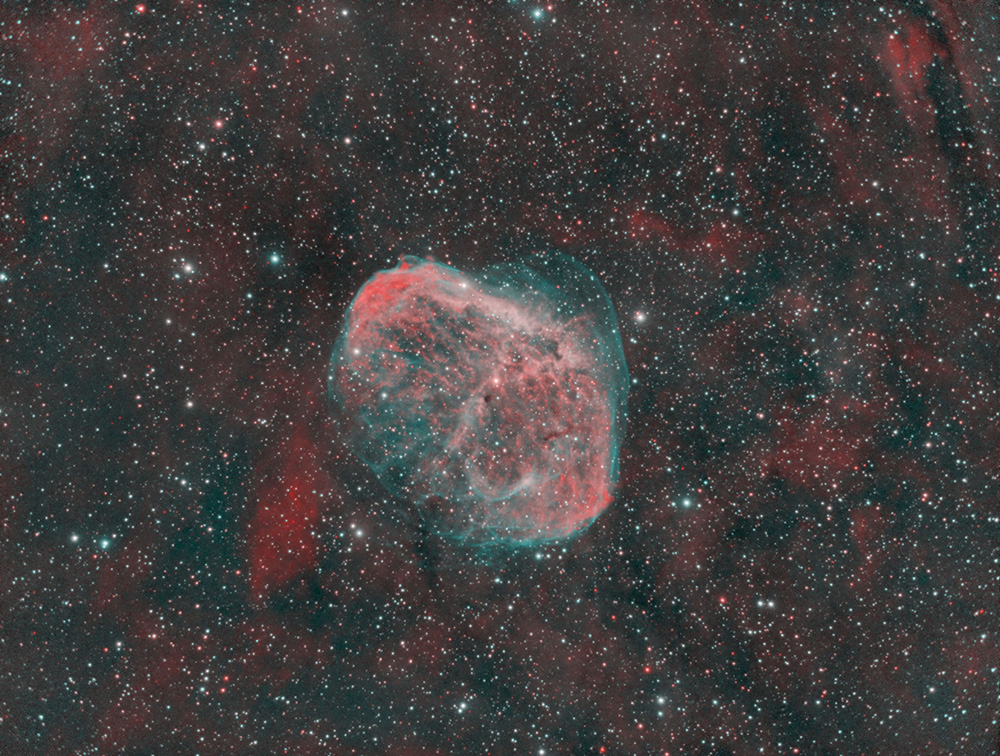

I approach color a little differently for narrowband images. These images are photographed with specific filters for each of three gasses. I often use the Hubble palette, which maps sulfur to red, hydrogen to green, and oxygen to blue. The reality is that hydrogen is by far the dominant gas. This method allows me to see each of the gasses separately.

©Molly Wakeling, Nebula region Rho Ophiuchi, in the constellation Ophiuchus, just off the western edge of the Milky Way.

©Molly Wakeling, The Rosette Nebula in false color, a stellar nursery located in the constellation Monoceros.

The Rosette Nebula is a good example. It’s got some darker regions and brighter regions that fade into each other in a gradient of color. When I’m adjusting the colors, I’ll make the darker areas a darker shade of red, with the lighter areas being a slightly different shade of red with a little more green, to have the colors flow nicely.

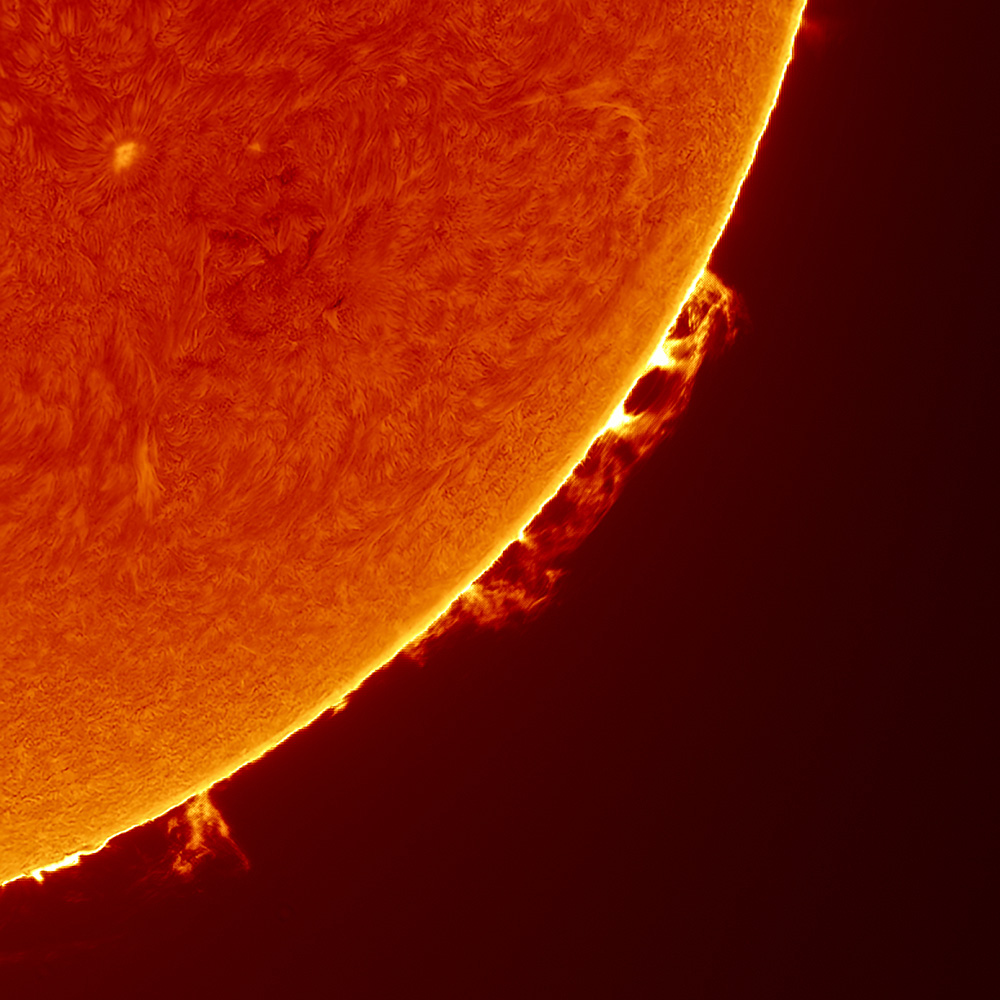

©Molly Wakeling, The Sun’s surface and prominences in false color, captured with a special solar telescope on July 22, 2023.

What’s next for you?

I’ve been working on photographing the Milky Way and nightscape images. I got an astro-modified DSLR which has made a world of difference on the quality of my Milky Way images. I’m looking forward to making more YouTube videos about astroimage processing and equipment.

I’d also like to find more places to share my images. I’d like more people to see how cool space is – particularly in a world with a lot of conflict and differences of opinion and angst. I’d like people like to think about something bigger than themselves, outside daily lives of this planet and pull back the view and look at something else. Remember that every person, everything that you know is just this little speck of dust. That puts all the world’s problems in a totally different context, and you cannot think about them in the same way.

Maj. Molly Wakeling, PhD, writes about astronomy and astrophotography for major publications in feature articles and regular columns, speaking engagements, star parties, YouTube videos and interviews. She is a regular host of The Astro Imaging Channel on YouTube.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Lee Gap-Chul: Conflict and ReactionJanuary 14th, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026