Photography Educator: Lynn Whitney in Conversation with Andrew Hershberger

Fig. 10. ©Lynn Whitney, Casting Yard, Glass City Skyway Project, Toledo, OH, 2004. Veterans Glass City Skyway Project. Gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in. From the Portfolio A Bridge for the 21st Century. Collection of the Toledo Museum of Art, OH.

Photography Educator is a monthly series on Lenscratch. Once a month, we celebrate a dedicated photography teacher by sharing their insights, strategies and excellence in inspiring students of all ages. These educators play a transformative role in student development, acting as mentors and guides who create environments where students feel valued and supported, fostering confidence and resilience.

For the month of November, I’m pleased to feature a guest conversation between educator and photographer Lynn Whitney and educator Andrew Hershberger.

Lynn Whitney: The Camera, A Compass

by Andrew Hershberger

Lynn Whitney earned a BFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt) and an MFA in Photography from Yale University. Soon thereafter in 1987, Lynn began teaching photography at Bowling Green State University (BGSU) in Ohio. After a 34-year teaching career, Lynn recently retired from BGSU in 2021. I first met Lynn in 2001 when I started working with her at BGSU. I arrived as a newly minted Ph.D. photo historian, and I was truly thrilled to teach alongside Lynn since I immediately felt a connection with a contemporary photographer using an 8×10-inch view camera with black-and-white film – like so many of the earlier photographers that I loved and had studied as a student and that I would be teaching in my own BGSU classes. Indeed, thinking of my own photo history teachers at Arizona State University (Van Deren Coke, Diana Hulick, and Bill Jay), and at the University of Arizona (Keith McElroy), and at the University of Chicago (Joel Snyder), and finally at Princeton (Peter Bunnell), all six of them loved photographers who worked with 8×10 cameras. Thus, I think of 8×10 view camera photographs as basically the ultimate in terms of visual interest within the medium. Not surprisingly, the stunning beauty of Lynn’s works immediately resonated with me. I was lucky to work with Lynn for so many years, and I miss working with her now, as the following conversation will show.

AH: Who was your first teacher in photography?

LW: My first teacher taught continuing education classes at MassArt. He was humble, unassuming, and terrific. His name was Ron Morris. Ron was instrumental in so many ways. Most importantly he introduced a foundation to making pictures that remains my core. He believed in what has been called the “straight” picture, exposing film for mid tones and printing without tricks. As well, he taught me to look at the world in a way that fit me. I recall that when he moved back to Louisville, a couple of his students helped him sort and pack up his belongings. For our support, he gave each of us a print of his own work. The print I received is of a lone Texas Longhorn, head and horns turned ever so slightly to the right, made from a distance of no more than a few yards, with an open sky and space, and with a perfect horizon line to meet the dark coat, white underside, and dark legs pinned to the ground beneath. That print still hangs over my desk (Fig. 1). Like Ron and how he saw the world, I saw how this Longhorn mirrored who Ron was. Both are drawn to or inhabit big spaces, both possess an air of resoluteness. And while I did not meet the Longhorn, I suspect that he and Ron shared a mutual kindness with and for their respective worlds. Sadly, Ron passed away in 2021.

Fig. 1. ©Ron Morris (1947-2021), Longhorn, Southwest, undated. Gelatin silver print, ~ 7½ x 9¼ in. Courtesy of Bridwell Art Library, University of Louisville, KY.

AH: In addition to Morris, who else did you study photography with in your own BFA and MFA programs?

LW: Reflecting the time period (and the times still haven’t changed all that much), almost all of my teachers were men: Nicholas Nixon, Baldwin Lee, Tod Papageorge, Richard Benson, and Thomas Roma. The few exceptions were Jo Ann Walters and Sage Sohier. I also took workshops with Joel Sternfeld, Gary Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander. While I was a student, several visiting artists, such as Judith Joy Ross, Nancy Hellebrand, and Nan Goldin supplemented the regular faculty at both MassArt and Yale.

AH: That is an incredible and interesting list. Thinking quickly, I recognize some 8×10 camera photographers in your list of teachers, including Nicholas Nixon, Joel Sternfeld, and Judith Joy Ross. Did those three (or others who used an 8×10) particularly inspire you? Did any specific works by those three photographers (or others who used an 8×10) capture your attention? As an example, easily one of my all-time favorite (and most surprising, especially when I first saw it) photographs has to be Joel Sternfeld’s McLean, Virginia, 1978, from Sternfeld’s wonderful book project, American Prospects, 1987.

LW: Yes, each and every one of the 8×10 people impacted me in different ways. Nancy Hellebrand lent me her 8×10 when I was a graduate student. She is a close friend now and someone whose courage and work I admire deeply. Nick’s unabashed way of handling the camera fluidly, as though it were a handheld camera (this has been said of course), but also his focus on the skin of everything – for me that is one of his consistent themes. His pictures are so much about the description of the skin that wraps or holds us in space, be it people or trees. Nick recognizes the special ability of the 8×10 and its lenses to articulate surfaces. His technical facility was way over my head, but I gravitated to his project-based way of working, and how he paired reading poetry and literature with making pictures in his classes.

As far as Joel goes, like you, Andrew, I fell hook, line, and sinker for the pumpkin shed/burning house picture as a student, believing the “truth” of it: how could that fireman take a pumpkin and not do his job? Joel also taught me about color. I have made just a few color pictures – something I now somewhat regret, given color’s accessibility and popularity. Joel posed the “truth” question in pictures for me, and he brought to my own time period a look at American culture after Robert Frank’s The Americans. My earliest undergraduate degree is in (what was then) American History and Civilization from Boston University. Then, as now, writing alongside strict academics was a challenge. As a way to avoid writing papers, I convinced my advisors to allow me to explore topics using my camera. For context, I had a darkroom at home throughout high school, and I was a yearbook photographer who convinced my old world, wonderful high school art teacher to allow my independent art project to be photographs – though he did not subscribe to the notion that photography could also be art.

Judith Joy Ross does everything I wish for in my own work. Honest portraits, not weighted by technique, always with a layer of her concerns for democracy, and our culture. She’s blunt, though careful not to overstate, and she’s obsessive in her search. She, like the others, fueled and continues to fuel my love of making pictures.

AH: Since I know that you have also used 35mm, 6x7cm, and 4×5-inch cameras earlier in your studies, why did you settle on the 8×10 format?

LW: I loved the 8×10 contact print, and I loved that I could enlarge it too. I loved that my presence in the world was obvious, and – to anyone paying attention to what I was doing – it made them curious and ask questions. I learned that being engaged in the 8×10 way – and being visible – made whatever I thought I was doing more clear to me and to whatever or whomever I was working with. My teaching colleague from 2000 to 2004, and a terrific former student and friend, Kevin Vereecke, helped me to find and to buy (not borrowed) my first 8×10 camera from eBay, in 2000. I’ve upgraded since then and for a long time now I have used a Keith Canham 8×10 camera.

AH: I love how we both know Keith as well, me from my Arizona days and you from owning one of his wonderful cameras. My next questions are: how long did you teach photography at BGSU? What are some of your favorite memories as a teacher?

LW: I taught photography at BGSU for 34 years in total. All my memories circle back to one thing: helping and watching my students build up their own confidence in seeing and thinking critically. My first year, I had a student, an Art History major, Stephen Tomasko, very bright and energetic and full of questions. He took to the darkroom, to the streets, and to photographs, and he changed his major to Studio Art even though he was almost ready to graduate. He was then, and still is, really good. He made wonderful pictures of my wedding in black and white and in color, traveling from here to the East Coast to do it as well. Now, his daughter is getting married to one of my son’s best friends from high school – a crazy coincidence.

Another memory I will share involves a court house project we did as a class. Students were assigned court houses to photograph for eventual display in the District Attorney’s Office in Toledo. We looked at Tod Papageorge’s court house pictures, among others, for guidance. My student and friend today, Lindsay Glass, read To Kill a Mockingbird aloud as part of the class. Her voice and that project stand out as a treasured memory. Lindsay is now Director of Community Engagement and Capacity Building for the Toledo Arts Commission. She was instrumental in helping me secure venues in Toledo to exhibit the photographs of Individuals with Developmental Disabilities from our Wood Lane Community Projects class for the Wood County Board of Developmental Disabilities here in Bowling Green.

And that brings me to the last but incredibly important memory: the Community Projects class. Dianna Lust Temple , a really remarkable student, now Executive Director of Ohio SIBS, came to me to suggest that she and I develop a class for students to explore the complexities and nuanced lives of individuals with developmental disabilities – so often outside the frame, and so often oversimplified by the general media or left unseen. Dianna and her client/friend Mark from Wood Lane are key to the success of our class (Fig. 2). My photography students taught, engaged with, and photographed with their Wood Lane partners. In the first year of the class, we curated a physical exhibition of the work at the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) in its Community Gallery, and we laid out a series for a book. Each subsequent year the class would curate, exhibit, and design a book, and members from the community – Wood Lane, the students, and outside people – all came together to celebrate these connections.

One student in particular, Clara Delgado, who enrolled in the class not once, but for three years, deeply engaged and contributed her energy while encouraging others to widen their lens to really see and to understand. A recent graduate from RISD with an MFA in Photography, Clara’s insight, ambition, plus humility, and her remarkable talent and ethic will, like so many others, make me proud that we found each other. It’s hard to name just a few students, I could go on forever. When I retired, Clara gave me the gift of a compass – an antique. She understood how powerful the camera is in finding one’s way.

Fig. 2. ©Lynn Whitney, Mark, City Park, Bowling Green,OH 2014. Gelatin silver contact print, 8 x 10 in. Artist’s Collection, OH

AH: It is a joy to remember your former students for me as well. For many years now, you’ve worked with a Master Printer. Please tell us how that relationship started and how your collaboration works today.

LW: My printer is a friend from MassArt, David Haas. He has worked for a number of artists including Larry Fink, Judith Joy Ross, and Nancy Hellebrand among others. When I first met David, he was the darkroom assistant for Gus Kayafas, and he worked for Palm Press in Littleton, MA (which moved to Concord, MA, later on). I began by assisting David with jobs and then began printing my own work with him assisting me at Palm Press. Gus had studied with Minor White at MIT, and Gus was the founding director of the MassArt undergraduate and graduate photography programs, and he had a tremendous network of photographers who sought his and David’s printing services. Lee Friedlander printed with Palm Press, and when one of his prints was ready to be examined in the light, Gus asked Lee: “What do you think”? Lee said: “I don’t know. Let’s ask the expert,” meaning, of course, David. Since then, Gus has worked with, among others, Aaron Siskind, Duane Michals, Harry Callahan, Helen Levitt, and Harold Edgerton. As a tagalong, I visited Harold “Doc” Edgerton’s darkroom to deliver some newly made prints. I was even given a print, and I remember being in awe that I was in the space of the man who had made that bullet go through the apple .

AH: Since you mentioned Gus Kayafas, and since I know that Kayafas had studied with Minor White, I’m just curious: Do you remember Gus or others at Palm Press talking about White? Did White’s printmaking techniques ever come up?

LW: Minor White was one of Gus’ influential mentors and teachers at MIT. When I worked at Palm Press, Minor White was brought up quite often. But only in reverence for him and his pictures. As I recall, we never printed any Minor White negatives. In my first days at Palm Press, Aaron Siskind’s negative was in the enlarger. I remember quite clearly how little I knew about making a print, especially one with so much more drama in it than I was accustomed to.

AH: During your career, you have created a number of sustained photography projects, including your recent Lake Erie project and your earlier bridge project in Toledo. Which of your own main photography projects would you like to highlight in this interview?

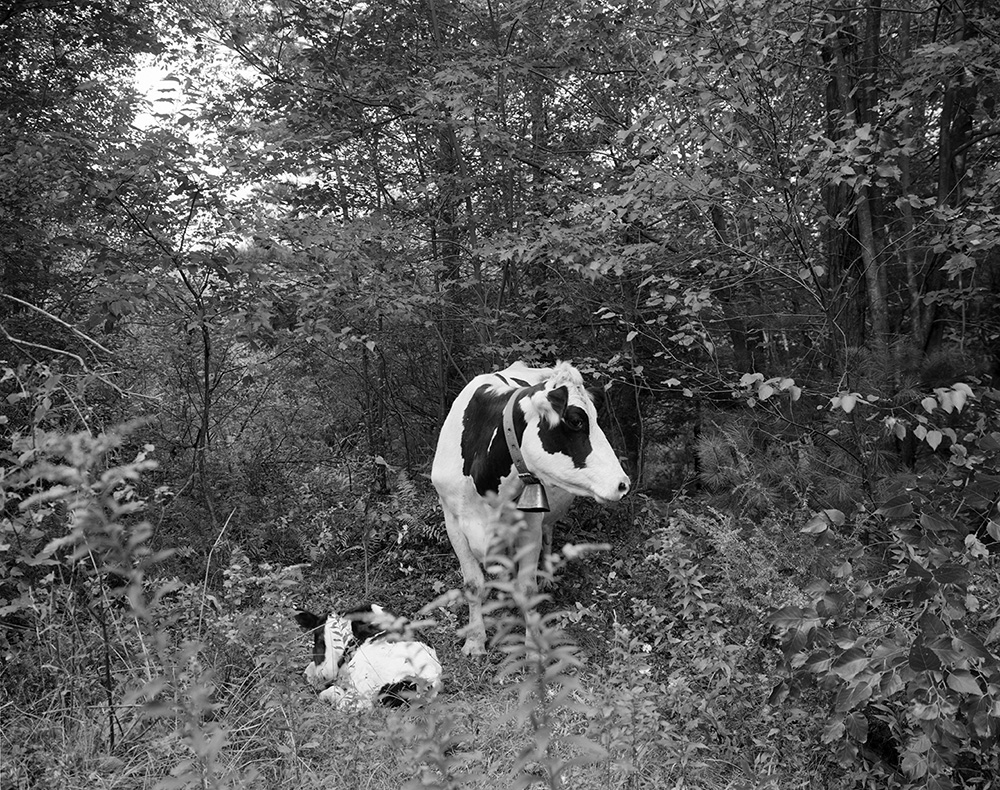

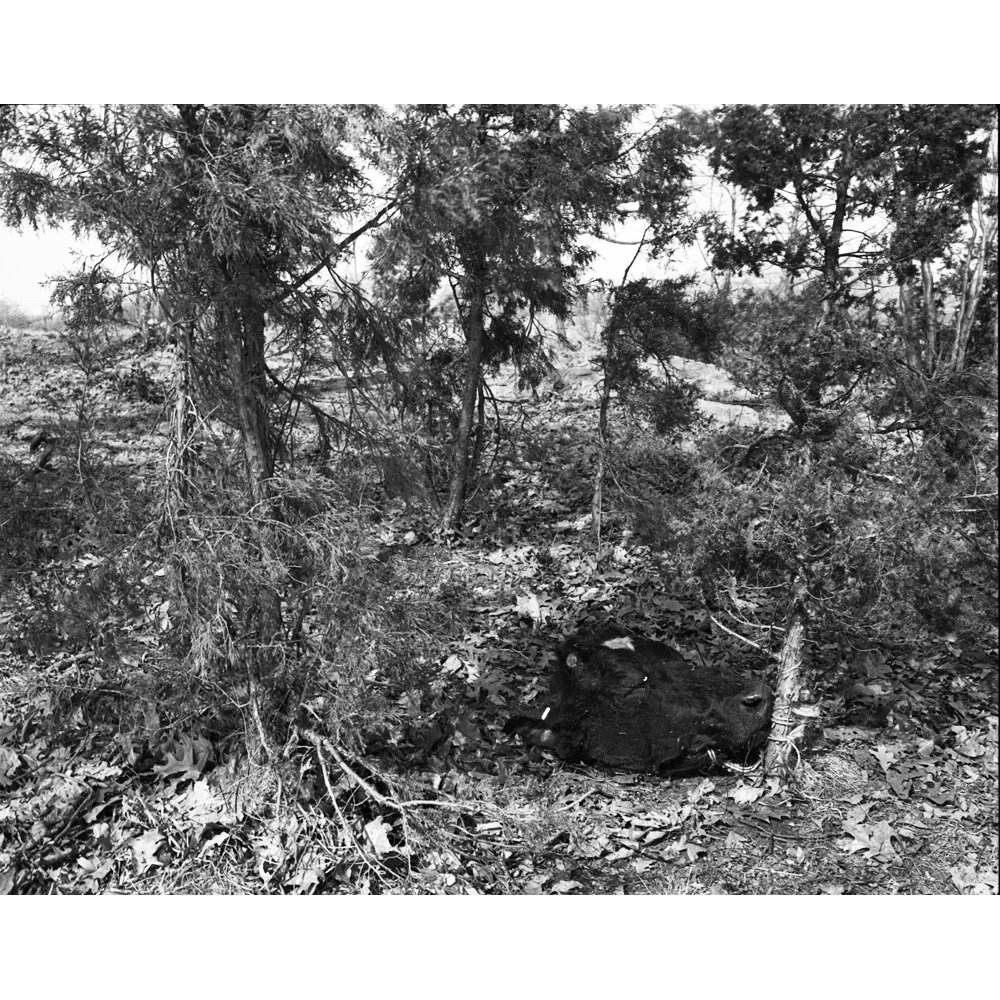

LW: I began making pictures of farm animals with a 4×5 camera. Probably these photographs came about because I wanted to see if I could communicate with the animals, and to see if I could will them into being still for my exposures. Or, maybe it was because my father had wanted to work on a farm, but his father forbade it. Or, it could have been because of my reading of Animal Farm, or maybe it was because I loved animals. In any case, the challenges were real and exciting and most of all magical, but then also alarming. The animal pictures began with such innocence and then they concluded with my eyes wide open to their collective fate (Figs. 3, 4, 5). I noticed, of course, the various landscapes and the manner of camouflage, and their aloneness and togetherness.

Fig. 3. ©Lynn Whitney, Brookside Farm. Belled Mother’s Calf. Westminster, MA, 1982. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 in. Artist’s Collection, OH

Fig. 4. ©Lynn Whitney, Field dress, off road, near Westminster MA, 1982. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 in. Artist’s Collection, OH

Fig. 5. ©Lynn Whitney, Sapling Grove with Cow Head, Upstate Connecticut, 1986. Gelatin silver print. 16 x 20 in. BGSU School of Art Gallery Collection, ex-Collection of Art Historian Dawn Glanz (1946-2013), OH

This aloneness and togetherness idea then led me to photograph women who chose to become Sisters in convents. I narrowed my focus in this project to novices or young nuns (Figs. 6, 7, 8). This work was a way for me to learn about a cloistered life whose sole purpose was one of devotion. Their daily practices were scheduled and their clothing was always the habit. The habit masked an individual’s full identity, delivering faces and gestures that were derived from a profoundly inward space.

Both of those early projects have, at their core, personal questions and searching. I wondered and was in awe of an animal’s instinctive routine and duties, and how they served humans and the land. And I wondered and was in awe of the Sisters’ commitment to their belief system, a system that had been practiced for ages. I made this work in the 1980’s. Things in photography were very different then as opposed to now, meaning access to things was a bit more free.

Fig. 6. ©Lynn Whitney, Sisters, Still River Massachusetts, 1983. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 in. Collection of Aurelia Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

Fig. 7. ©Lynn Whitney, Novitiate and wooded walk. Abbey of Regina Laudis, Bethlehem, CT, 1984. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 in. BGSU School of Art Gallery Collection, ex-Collection of Art Historian Dawn Glanz (1946-2013), OH

Fig. 8. ©Lynn Whitney, Summer Camp, Sisters of the Order of St. Benedict, Bethlehem,CT , 1984. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 in. Collection of Aurelia Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

The bridge project came from a different part of me. In 2003, I was commissioned by the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) to photograph the FIGG designed I-280 bridge construction now known as the Veterans Glass City Skyway (Figs. 9, 10, 11). Here was a chance to honor some of my other heroes from the history of photography: Lewis Hine, Berenice Abbott, and Walker Evans. Using the 8×10, I initially had access to the construction site wearing a hard hat, boots, and a yellow vest. Then there was a terrible accident (not near me) and some workers died and new restrictions were imposed. The new restrictions were a good thing. I was assigned an escort who was great, but, of course, another person that I worried about. I asked myself: Was she okay? And, was what I was doing okay? In the end, the portfolio consisted of 20 x 24-inch gelatin silver prints, 26 in number, and all housed in the TMA’s wonderful collection. The Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art, Jehan Mullin, recently found them and has given them space (three at a time) in one of the galleries, which has made me very happy.

Fig. 9. ©Lynn Whitney, Cantilever from the East, Toledo, 2007. Veterans Glass City Skyway Project. Triptych, gelatin silver prints, 10 x 24 in. overall. From the Portfolio A Bridge for the 21st Century. Collection of the Toledo Museum of Art, OH.

Fig. 11. ©Lynn Whitney, Center Pylon, Glass City Skyway Project, Toledo, OH, 2006. Veterans Glass City Skyway Project. Gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in. From the Portfolio A Bridge for the 21st Century. Collection of the Toledo Museum of Art, OH.

Finally, with my recent Lake Erie project, the threads of my curiosities and themes more or less all come together. This work began as a commission as well. The George Gund Foundation in Cleveland and Mark Schwartz honored me with the opportunity to photograph Lake Erie, in Cuyahoga County, OH. This is/was a big deal because many of my favorite photographers and friends were among those who had been granted an earlier Gund Commission, including Frank Gohlke, Barbara Bosworth, Nick Nixon, Thomas Roma, Lee Friedlander, Andrew Boroweic, Judith Joy Ross, Sage Sohier, Andrea Monica, Lois Connor, and Mark Steinmetz. Lake Erie as a body of work attempts to address a multi-layered set of issues: from its environmental health, to it being central to a long history of “use,” to the lake’s existence both commercially and recreationally (Figs. 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). Lake Erie’s shallow depth produces quick turning weather patterns and emotions, and it harbors a danger somewhat masked by the illusion of vastness. I saw Lake Erie and I related this body of water to the female experience. In the end, this work brought together my thoughts in a way that was both unexpected and complete.

Fig. 12. ©Lynn Whitney, Cellphone, Cahoon Memorial Park, 2009. Gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in. Artist’s Collection, OH

Fig. 13. ©Lynn Whitney, Climate Test, Edgewater Park, 2009. Gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in. Artist’s Collection, OH

Fig. 14. ©Lynn Whitney, “BITCH,” Mentor Headlands, 2013. Gelatin silver contact print, 8 x 10 in. Artist’s Collection, OH

Fig. 15. ©Lynn Whitney, Signal, near Sandusky, 2014. Archival inkjet print, 27 x 34 in. Collection of Roger and Katerina Ruedi Ray, Ottawa Hills, OH

Fig. 16. ©Lynn Whitney, By the Great Lake Erie, Magee Marsh Beach, “Biggest Week,” 2019. Archival inkjet print, 27 x 34 in. Artist’s Collection, OH

AH: In relation to your projects, how do you figure out what you are going to photograph? How do you start a project, or what motivates you at the beginning?

LW: Initially, and probably still today, making pictures has been my way of collecting what I love. I saw a Paul Strand portrait ages ago, the Young Boy, Gondeville, Charente, France, 1951. The beauty there in the boy’s expression of confrontation mixed in with a certain androgyny was astounding, and I felt that this is how I wanted to work. I hoped I would be able to make pictures that contained the beauty as well as the sharp edges with which we must live in this world. This is a much more complicated question for me to answer in sentences, but basically, I ask myself to consider looking at things or places that I don’t know but that I want to find out about, because I love the way these things, people, or places look visually. The more I engage with them, the more I learn about my relationship to those places, people, or things, and my world view opens wider. I don’t start with a point of view or opinion, but in the process of going back again and again it obviously has an impact on how my pictures as a group finally read.

AH: Congratulations on your many recent exhibitions and on your recent Lake Erie book too! Which of your exhibitions would you like to highlight for this interview?

LW: I’d probably choose my April to May, 2025, solo show at the River House Arts Gallery in Toledo. To have been asked to exhibit there was an honor and, to be honest, a surprise too. Paula Baldoni works tirelessly for art and for her gallery. I was thrilled she took me in since I know very well that undramatic black and white photographs are not an easy sell. I was proud to see a selection of Lake Erie pictures in the show. I was really pleased with the expert hanging done by Paula’s Gallery assistant too. Additionally, my husband Claude’s intuitive, intellectual eye for sequence and spacing made the Lake Erie work read as I hoped it would.

AH: You recently attended Paris Photo and signed copies of your Lake Erie book there too. Please tell us about that experience.

LW: Paris Photo was incredible. The week was jammed packed with booth exhibits, art talks, and book signings. Kehrer Verlag was tremendous in featuring my Lake Erie book among all their other top-notch publications. I was honored to meet Todd Hido as well, a native of Ohio who stopped and took a look at my book and said to me something along the lines of: “How come I’ve not heard of you? This is a really nice book.” It was a memorable and unexpected moment for me, and one of the true highlights of being at Paris Photo alongside being in Paris of course.

AH: Next time you go to Paris Photo I’d love to come with you! Thanks so much for doing this interview with me. A few of the ideas you mentioned earlier stick out in my mind. If I remember correctly, I think, for you, making pictures provides you with a compass that gives you confidence in seeing and also allows you to engage more deeply with all that you love. If that’s accurate, please share with us your concluding thoughts about what those ideas mean to you. Thanks again!

LW: I hope I have conveyed some sense of what I mean with the answers to your questions. It is difficult for me not to sound sappy answering why I photograph as a way to engage with all that I love. I hope that my pictures are beautiful visually and also convey complexities. I can’t just make a “pretty picture.” I use the camera as a way to help me find meaning and then to find my own voice. I’m a quiet person, but it’s also been difficult for “women of a certain age” to speak up, and to trust our thoughts. I’m really lucky that I grew up when photography was also finding its place in the art world.

AH: Thanks again so much!

About Lynn

Artist Statement

Making photographs is my means to pose and then, as thoughtfully as possible, to examine the world and our place within it. The landscape figures prominently in all of my pictures and, as it is considered by some to align with the female, these ideas are often seen together, highlighting contemporary issues.

I use large format and medium format film cameras. Providing both a cover and a presence for whatever or whomever I might encounter, the camera’s generosity extends to my content.

My early pictures explored farms, the military, the convent, and family. I was and I am curious about how individual human beings remain as such within those constructions, and how they commit to serve concerns larger than themselves. I wondered and marveled at their courage – through choice or lack of options – to dedicate themselves to a lifelong endeavor.

Two commissions, photographing the construction of the FIGG-designed Skyway Bridge over the Maumee River (in Toledo, Ohio) from the Toledo Museum of Art, and photographing Lake Erie along Cuyahoga County (Cleveland) from the George Gund Foundation, helped both to broaden and to provide depth to my cultural questions and concerns. My most recent work focuses on Lake Erie, and it is tied to my earlier interests and expands them through living, teaching, and aging.

Over thirty years ago, the concerns shared above traveled with me to the Midwest, from my home where Henry David Thoreau lived, and wrote : “A lake is the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is Earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.” Women and water are and have been seen as an endless resource to use, misuse, and abuse. Placed together the pictures speak about fragility, vulnerability, and the seemingly endless capacity to “take it.” The nuances and qualities of the lake and/or the surrounding land mirror what we have done to it, and to each other, and they ask us what the chances for our collective future might be.

Bio.

Lynn Whitney is Associate Professor Emerita in the School of Art at Bowling Green State University in Bowling Green, Ohio. She has served as the School of Art’s Associate Director, 2017–2020, Studio Division Chair, 2006–2017, and Head of Photography, 1987–2020. Lynn earned her BA in American Culture Studies from Boston University, her BFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and her MFA from Yale University’s School of Art. Among her awards, Lynn has received commissions from the Toledo Museum of Art, the George Gund Foundation in Cleveland, and an Individual Artist Grant from the Ohio Arts Council. Her work is in the collections of the Toledo Museum of Art, the George Gund Foundation, Columbia College’s Midwest Photographer’s Project, The Cleveland Clinic, Ohio Humanities Council, the Southeast Center for Photographic Studies, and Yale University.

Website: www.lynnwhitneyphotographs.com

About Andrew

Dr. Andrew E. Hershberger, Professor of Contemporary Art History at Bowling Green State University, received a Ph.D. from Princeton. A specialist in the history of photography, he has held the Ansel Adams Fellowship at the Center for Creative Photography (AZ), the Coleman Dowell Fellowship at NYU, the inaugural John Teti Fellowship at the New Hampshire Institute of Art, a Visiting Fellowship at Oxford (UK), and a CIWAS Resident Fellowship at the Cody Institute for Western American Studies (WY). Most recently, Hershberger was selected to join with an international group of twelve professors at Yale for their Summer Teachers Institute in Technical Art History (STITAH). Hershberger has published multiple peer-reviewed articles in the journal History of Photography, and he has refereed articles in the Art Journal; Early Popular Visual Culture; Analecta Husserliana; the Journal on Excellence in College Teaching; Academe; Materia: Journal of Technical Art History; and Arts of Asia. Hershberger has published a large (86 edited articles) compendium entitled Photographic Theory: An Historical Anthology (Boston and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell). The Society for Photographic Education (SPE) selected Hershberger for an SPE Insight Award.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Lynn Whitney in Conversation with Andrew HershbergerNovember 14th, 2025