Dawn Roe: Super|Natural

“Dawn Roe: Super|Natural” Installation at the Tracey Morgan Gallery November 29th, 2025 – January 10th, 2026. Installation photograph by @Eric William Carrolll (with additional modifications by the artist)

Dawn Roe recently opened a expansive solo exhibition, Super | Natural, at the Tracey Morgan Gallery that runs through January 10th. This marks Roe’s third exhibition with the gallery and brings together works spanning almost five years of activity from the artist’s indefinitely ongoing series, DESCENT ≈ An Atlas of Relation, a collective archive of earth, plant, and animal forms living and dying together across both great and small distances. Occupying the liminal space(s) of water-based worlds permanently re-shaped by extractive actions and colonial forms of “species management,” the many Beings gestating within and along these waters endure ongoing disruptions, forever altering how these spaces have and continue to function as home, and community.

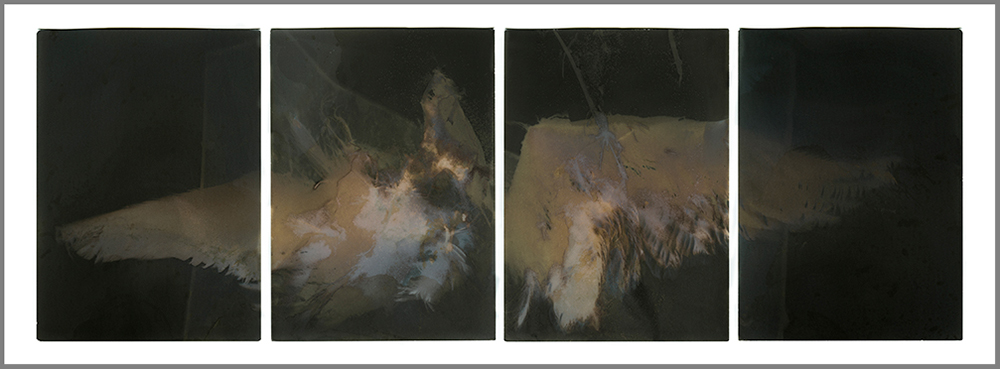

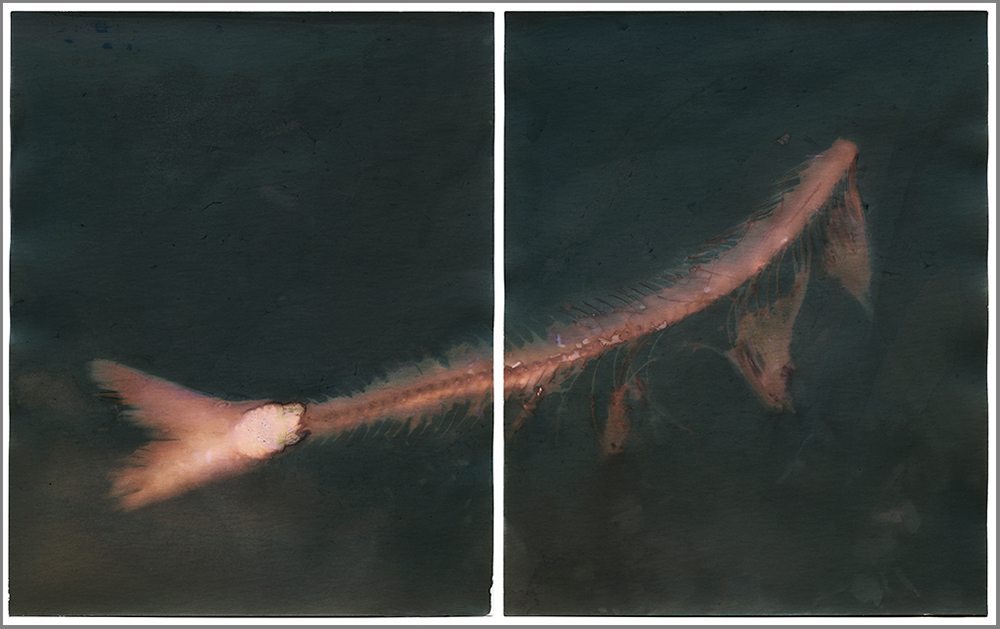

Roe questions our understanding and use of the terms “nature” and “natural,” while embracing spectral associations of the haunted and the ghostly. As with past projects she draws our attention to magical aspects of the elemental, the often hidden, or the overlooked. References to and from feminist theory, literature, and folklore circulate throughout the varied print and video forms. Her ongoing investigations into camera-less methods continue to probe the possibilities of representation for more-than-human voices. Multiple photosensitive materials and processes are deployed including direct animation of riparian vegetation on Super 8 film; derelict fishing gear (also known as ghost net) on X-ray negatives referencing emergent forms within the latent image; and digital still and moving image composites merging temporal and visual scales of fish and fish habitats.

Accompanying the exhibition will be a print-on-demand zine with text contributions by feminist environmental humanities scholar, Dr. Astrida Neimanis. The subtitle for the zine (and title for a related work), we only see by the water in our eyes, comes from a moment on the Multispecies Worldbuilding podcast where curator Sarah Lookofsky spoke with poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña about a beautiful phrase she had written – that “the reason we see is because of the water in our eyes” – such a perfect and sort of haunting notion, leading to thoughts not only of our sight as human being(s)/bodies, but the fascinating eyes of other sighted creatures. In the spirit of reciprocity modeled by contributor Astrida Neimanis, as well as the many other people and organizations Roe has come to know through her ongoing work on this project, 50% of any artist proceeds from works sold will be donated to underfunded land and water advocacy groups throughout Western North Carolina.

An Interview with the artist follows.

©Dawn Roe, The river that connects what were once our grandparent’s homes (for my brother), 2023 Composite pigment print of scanned UV-exposed gelatin silver prints and digital images

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography.

Wow, I think about this a lot actually. And my current work – what I’m fairly certain is simply going to be an indefinitely ongoing, continuous project – is absolutely shaped by this. And I suppose this might be the case for many of us who find ourselves enthralled with photography as a medium we choose to work with as artists, because of how we came to know it as newly forming humans. I fell in love early on with the photographic image as a material record of our existence, as well as a magical manifestation of time and presence. And, I do think there is something to the fact that some of my earliest memories involve sitting on an enormous braided rug covering the cold tiled floor in my grandparent’s house that sat along the St. Marys Rivers in my hometown of what is now called Sault Ste. Marie, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The front room had a huge picture window (what a telling term) that looked out upon the water where massive freighters would slowly pass across my field of vision.

I would sit facing this view, surrounding myself with stacks and stacks of these little red, square plastic books that held a random array of family snapshots, as well as older style photo albums with the black paper and photo corners that archived the earlier generations of ancestors, embalmed in black and white. And I wonder if my young mind noticed something about the precision of those earlier forms of photography, and how the silver helped make the image – the way you could just kind of see that sheen on the surface sometimes. I can’t help but think the bodily memories generated from these embedded perceptual sensations perhaps made me more attuned to the photograph as something special.

©Dawn Roe, someone was calling out to return to the air (bones & fiber), 2024 digitized, gelatin silver x-ray film

Congratulations on the exhibition, how did it come about?

Thank you! Much of what I just ruminated on above has a lot to do with how this exhibition came to be. For various reasons, I had been wanting to make my way back home to see if I might not be able to create work in a place that is somewhat fraught for me as it now harbors quite a bit of personal loss, and is also a tricky place environmentally and culturally. Strangely, the travel restrictions of the pandemic led to circumstances that would allow me to spend extended periods of time with my family in my home region. I mentioned the St. Marys above – this is the anglicized term of the river French Jesuit missionaries named Saint Marie upon their arrival to this place that already had a name. This waterway links the town the French designated as Sault Ste. Marie (for the falls of Saint Marie) to the big, great lakes on either side, and eventually to the sea. These settlers would have been introduced to these waters and this place as Baawaating, the Anishinaabemowin place name that denotes the “place of the rapids” and recognizes how this community came to be, precisely because of the waters, and the fish. It’s a place that is still very special for these reasons – particularly to members of the tribes that make up about 20% of the population in the city and its surrounding townships (substantially more if the families living a river’s crossing away in what has now become Canada are considered).

This is maybe a lot of backstory, but these are the waters that “grew me up” (as I’ve heard hydrofeminist scholar Astrida Neimanis* lovingly say). For a long time I’ve tried to think about what that means, and how I got there – as someone from settler ancestry – and what home means to me, more generally. Not unlike the fish, I have always been a very transitory being, making my home in many places, at different times – but, differently from certain involuntarily displaced fish species, my transitory nature is my own choice, which is quite relevant, as well.

I have photographs from my baptism that I’ve fixated on for years – I’m being placed under water that has been deemed holy, but is most certainly drawn from the St. Marys River – and my godfather is in this image. His name was Maurice (Mo) LeBlanc and I really only ever knew him through these pictures. He was the best friend of my father, who of course is also in the pictures. Both of them are gone now.

©Dawn Roe, DESCENT ≈ An Atlas of Relation (Video Still), 2023 single-channel HD video loop (silent) on monitor over adhesive vinyl

One afternoon several years back I was randomly looking into old newspaper archives from our small town looking for any stories about them. One article from 1973 was quite a shock to me – embarrassingly so, as it recounts a history I should have been aware of. The article details – in derogatory language – the most recent arrest of my godfather, a member of the Bay Mills Tribe, who was repeatedly cited for “illegal fishing.” The article glibly makes note of the fact that Mo claimed to be exercising his treaty fishing rights, which of course he absolutely was. This is not an uncommon story across the Americas, and there are a number of pretty well known court cases re-establishing treaty hunting and fishing rights – including one that originated with the Bay Mills Tribe.

But, that I was unaware of this rich history in my own community has been deeply troubling. So, this is one of the reasons I started thinking with the fish, and gently creating pictures and recording film and video of and with their bodies as I learned of their various plights within these lakes and rivers. I titled the first section of this ongoing project, DESCENT ≈ An Atlas of Relation, alluding to the fish who find themselves living and dying within both familiar and strange waters, and the intertwined nature of biological evolution and ancestral heritage.

©Dawn Roe, with(in) the Bay; adikameg; Coregonus clupeaformis; lake whitefish, 2020/22 Pigment print of scanned UV-exposed gelatin silver prints

I’ve since continued thinking through these ideas in various other “home” spaces as well as a few sites where I’m a more temporary visitor. In each instance I’m working through how to respectfully engage with land and water as an uninvited guest while exploring different ways to visualize interspecies relations. I’m incredibly fortunate to have been given the opportunity to bring these works from the last five years together in this current exhibition.

*Astrida Neimanis very generously provided a text-response the artist’s book that accompanies the exhibition. A free digital version is available HERE.

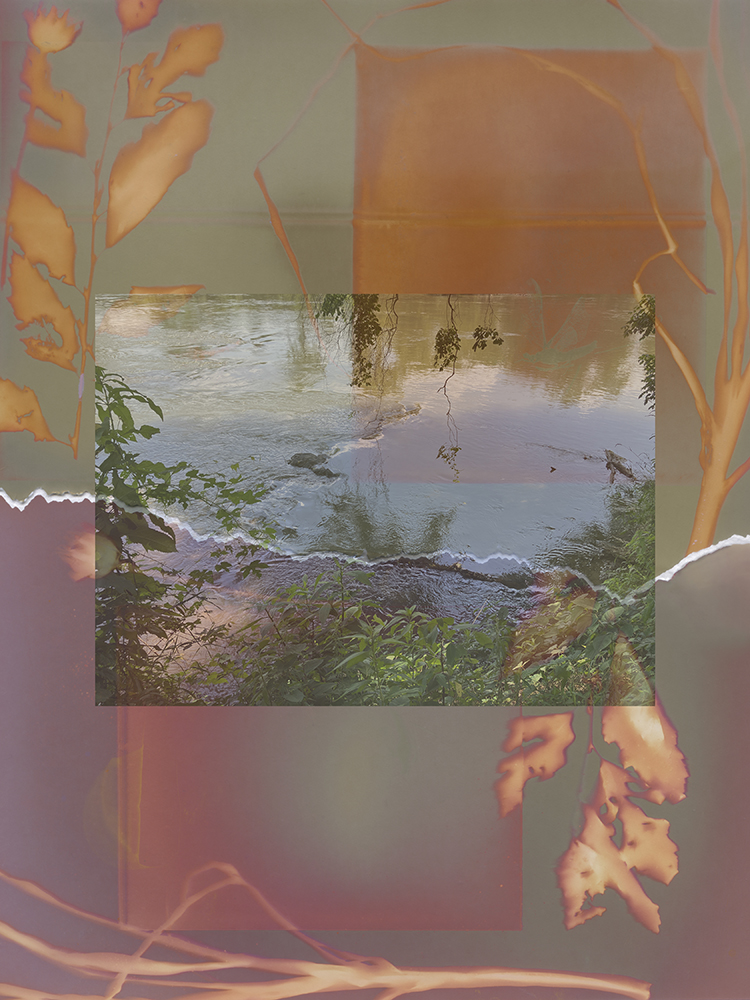

©Dawn Roe, torn river, 2025 composite pigment print of scanned, UV-exposed gelatin silver prints and digital image

Can you share the focus of the work, and the range of processes you’ve used? Your statement about how you work is so fascinating: “Combining a documentary approach with direct intervention, my process incorporates multiple reproductive methods including analog and digital imaging, film, and video. Recording both routine and remarkable encounters, I visualize the cohabitation of species as a collective endeavor”

Following from the project’s origin I described earlier, I can share that one of the reasons I deliberately incorporate the methods listed above has much to do with my continued reckoning with the historic and continued use of the photographic image as a colonial tool and the harm this has brought to people and communities who/that have been surveyed or surveilled. These are some of the earliest uses of the documentary image, and often even photographs made with “best intentions” reiterate myths of ownership or truth that can be hard to shake. So, I guess I try to be very straightforward in acknowledging these aspects of documentary in my own imagery by clearly intervening as means of insinuating my own actions as fabrication and, in the case of the moving image, to incorporate a quasi-performative element where my body becomes part of the record, often visualized along with other living Beings in a sort of perpetual, timeless cycle. This is maybe what I mean by the “cohabitation of species as a collective endeavor.”

And my use of camera-less methods offers another type of archive, one that alludes to the (presumed) stability of the specimen – itself a problematic notion – by marking moments of encounter with the fish and their watery friends in their living and dying forms, while thinking through how different forms of so-called species management and the re-shaping of waterways through extractive processes have impacted their habitats and, by extension, the many other life forms within, under, and along the water and the water’s edge.

These printed forms attempt to honor the life of each creature by holding the time of encounter with the help of tiny crystals of silver that are freed by light energy and time. I enjoy thinking of photography as alchemy – the super natural. I was hesitating about using that word and made a post on Instagram with some images that sort of confirmed my commitment over the summer and I love that my undergraduate photography professor, Rich Rollins, commented – isn’t it all!? And yes, I think that’s true. Both the routine, and the remarkable.

©Dawn Roe, thirty-six images of a dying horse (as alike as intelligence could make them) – after Hollis Frampton (detail), 2025 18, UV-exposed gelatin silver prints on fiber-based paper

Please share the experience of seeing the work on the wall and how you create such creative installations.

I’ve been showing work with Tracey Morgan Gallery for several years now, and am fortunate to have quite a bit of freedom in terms of the type and form of works I bring together in my exhibitions. I’m grateful the gallery allows me to explore installation methods that expand across floors, into corners, and up toward the ceiling. This is how the world reveals itself to us, in a dynamic and non-linear form. For some time now I’ve been working to find ways to most effectively combine the still and moving image and quite often incorporate prints on large-scale wall vinyl to facilitate a visual relation between components. In this instance, the looped videos on basic, commercial monitors live directly alongside the framed, print works placed in orientations that correspond with the background imagery.

Super | Natural, Tracey Morgan Gallery Installation photograph courtesy ©Eric William Carroll (with additional modifications by the artist)

It’s a (challenging) joy to put things together in a way that invites the viewer to have an experience that I hope is both slow, and poetic enough to invite contemplation of what is being seen, and just on the cusp of a producing a slightly frenzied response as a way of heightening awareness, kind of how Ursula Le Guin speaks of her science fiction writing as “a way of trying to describe what is in fact going on, what people actually do and feel, how people relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story. [S]till there are seeds to be gathered, and room in the bag of stars” (Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 1986).

©Dawn Roe, this is a song about a witch (detail), 2025 6, UV-exposed gelatin silver prints on fiber-based paper

What do you hope the viewers will take away from the work?

This is a show about love and care, at its core and – I hope – a recognition of the power of land, water, family (in all of its varied human and more-than-human) forms, and community. There are small and big stories behind all of the works included in the show, but something common to them are the way(s) we deal with and comprehend death and loss while finding ways to hold onto all the life that precedes it.

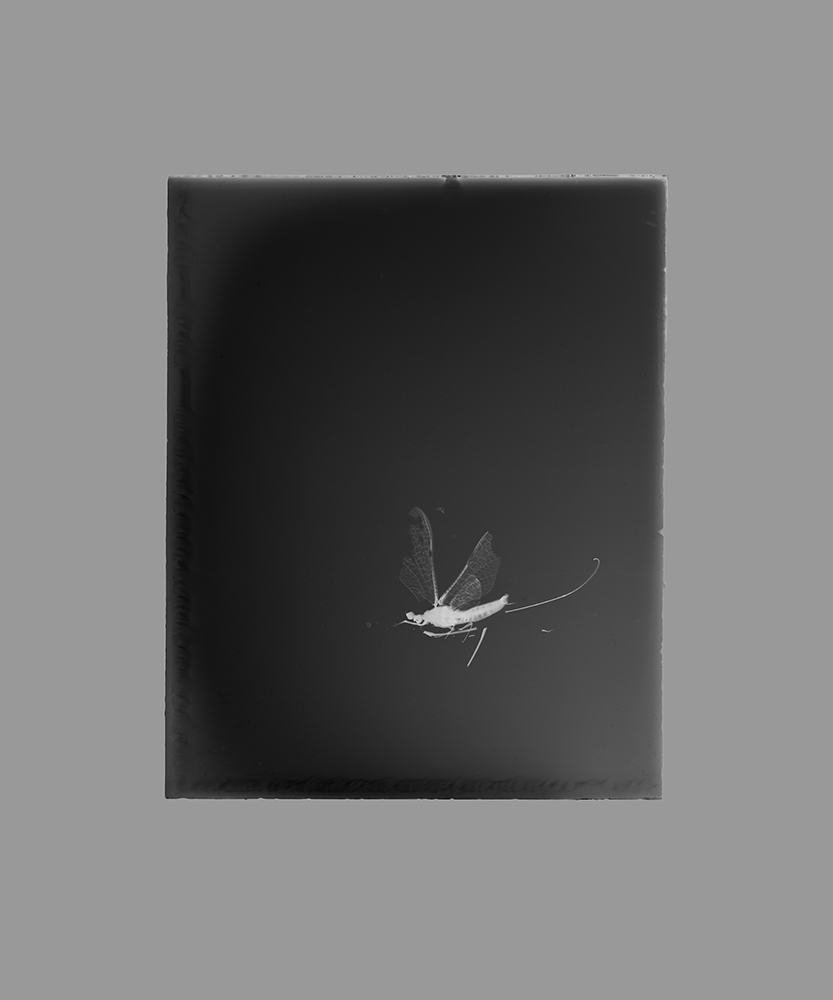

©Dawn Roe, broken mayfly (in memory of a friend on the afternoon of their death), 2024 digitized, UV-exposed glass plate negative

Did the floods in Asheville inform your work?

Quietly, yes. The storm was so painful for all the living Beings in the region, and this very much lingers. I’m hesitant to claim this experience as my own as I was in-between home spaces due to my teaching obligations at the time of the storm, and it was my husband who felt the impact and the aftermath more acutely in his daily interactions within the community. We were incredibly fortunate in that our house sits up on a hill and sustained no damage, but many of our friends and neighbors are still recovering from loss.

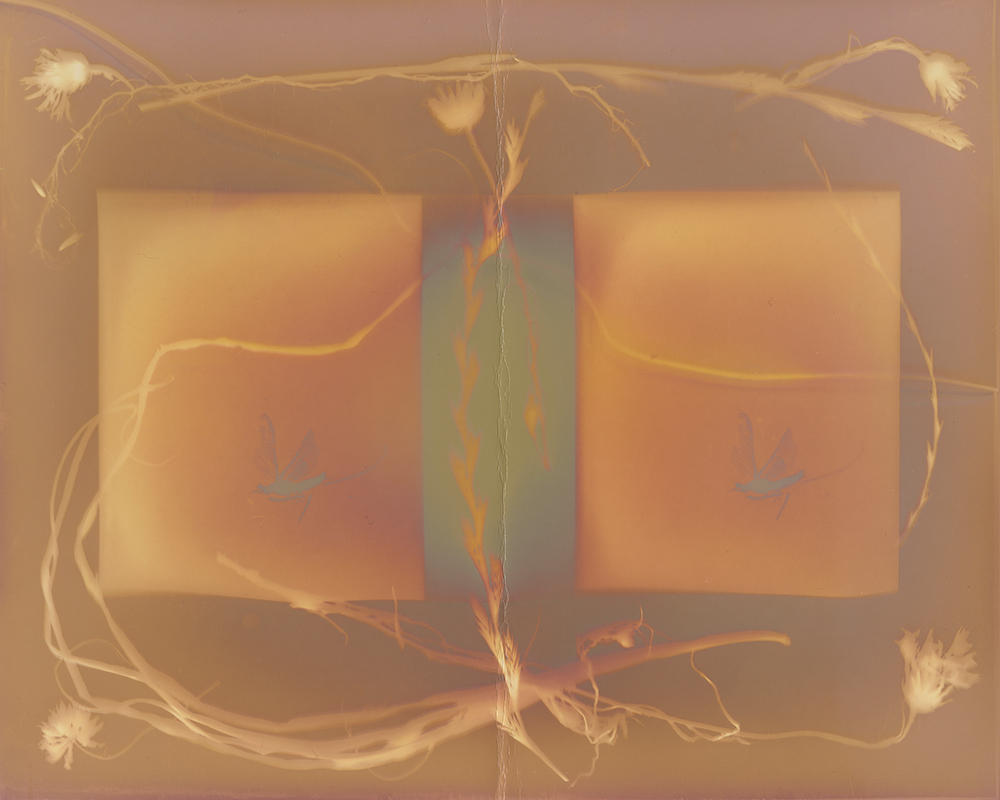

I did, though, process some of this experience by creating images in response. Several of the works in the exhibition were created during repeated visits to small sections of the river currently known as the French Broad not far from our home here. The creation of the two-panel piece, place thinking with an old river before and after the flood (plant remnants; sediment; water; time), spans a timeframe extending prior to and beyond these recent climate events that drastically impacted the watershed. In two instances – on my birthday in early July about three months before the flood, and the winter solstice following the floods about three months after – I placed fallen flowers, twigs, and roots atop delicate glass-plate film situated along the water’s edge, held in place by the compacted sands. As prints, they sit side by side and retain the purple hue of the scanned, unfixed negatives with the petals and woody textures rendered as ethereal forms situated amongst occasional golden flakes of matter.

©Dawn Roe, place thinking with an old river before and after the flood (plant remnants; sediment; water; time), 2024/25 digitized, UV-exposed glass plate x-ray film (unfixed)

The floods brought significant and life changing loss to many and it’s difficult to find words or images that feel correct to share, still. I think of how Donna Haraway describes our response-ability as ethical human actors, and one of the ways I’m attending to this through my own actions is by donating 50% of any artist proceeds from potential sale of my works in the exhibition to underfunded land and water advocacy groups in the region.

What’s next for you?

So much of my work unfolds from unexpected encounters, and the constant cycling of thoughts, sensations, and perceptions. I might have physically created an image or set of recordings weeks, months, or even years before I end up folding them into something else. Happenstance encounters also tend to direct my practice, at times. A recent example of this involves an episode of the Multispecies Worldbuilding podcast, where I heard curator Sarah Lookofsky speak with artist, poet, and gentle/fierce human Cecelia Vicuña about a beautiful phrase she had written – that “the reason we see is because of the water in our eyes” – and I really fixated on this beautifully haunting and visceral notion. I loosely transformed the phrase into, “we only see by the water in our eyes,” which is now the subtitle for the booklet that accompanies the exhibition as well as a title for one of the works.

It’s a perfect echo to the Super | Natural, I think. But I recently wrote and thought more about this while preparing a short talk titled, What if the H(a)unted Could Make Images?, for an anthropology conference panel. There is much more I find myself continuing to ponder as I pull on these threads. Finding time for future collaborations with my anthropology and environmental science and humanities colleagues accompanied by continued visits with our human and more-than-human land and water communities are goals of mine that I will patiently keep working toward.

Dawn Roe (b. 1971, Sault Ste. Marie, MI) was born and raised amidst what are now known as the Great Lakes where she developed a long term interest in land/water relations between human and more-than-human communities. Informed by early studies in experimental filmmaking and darkroom-based photography, her site-responsive practice combines historic and contemporary photographic methods with digital video to examine the role of these media in shaping personal and social understandings of our environment. Roe serves as Professor of Art at Rollins College. Her work is represented by Tracey Morgan Gallery in Asheville, NC.

Instagram: @dawnroe

Statement: Working within and between the still and moving image, my projects explore the role of these media in shaping personal and social understandings of our environment(s). Using photographic methods as observational tools, I respond to sites and situations where human and more-than-human lives entangle, often drawing on grief and despair as generative modes of being. Combining a documentary approach with direct intervention, my process incorporates multiple reproductive methods including analog and digital imaging, film, and video. Recording both routine and remarkable encounters, I visualize the cohabitation of species as a collective endeavor.

Recognizing my response-abilities as a white woman from settler ancestry I approach land and water tentatively, as an uninvited guest. Sensitive to the role of landscape photography in perpetuating colonial mythologies, I made a deliberate decision in recent years to supplement camera-based images with (potentially) less mediated photographic processes including cyanotype prints and other UV-light sensitive techniques. These durational methods require long exposure times relying on direct contact with physical material to produce an imprint, allowing for prolonged engagement. I create these images as one way of seeking a deeper, more embodied connection to the mass of life that surrounds us.

My observations become re-presentations, transformed and replicated as sequential and composite screen and print-based forms, stressing the fragmentary nature of perceptual response. The ephemerality of physical elements made intangible through film and video recording differs from the printed reproduction – a stable frame that persists, suggesting all matter is sound enough to endure inevitable and relentless shifts, however benign or catastrophic. As we struggle to orient ourselves within a shared global space that is rapidly transforming, I find uneasy comfort in visualizing our lived and perceived world as one of repeated disappearance and return. – Dawn Roe

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Landscape ReEnvisioned Exhibition At the Monterey Museum of ArtFebruary 26th, 2026

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026