Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022

“A single photograph may not change the world in one fell swoop, but it can change a person’s mind, which is where change begins.”– Ed Kashi

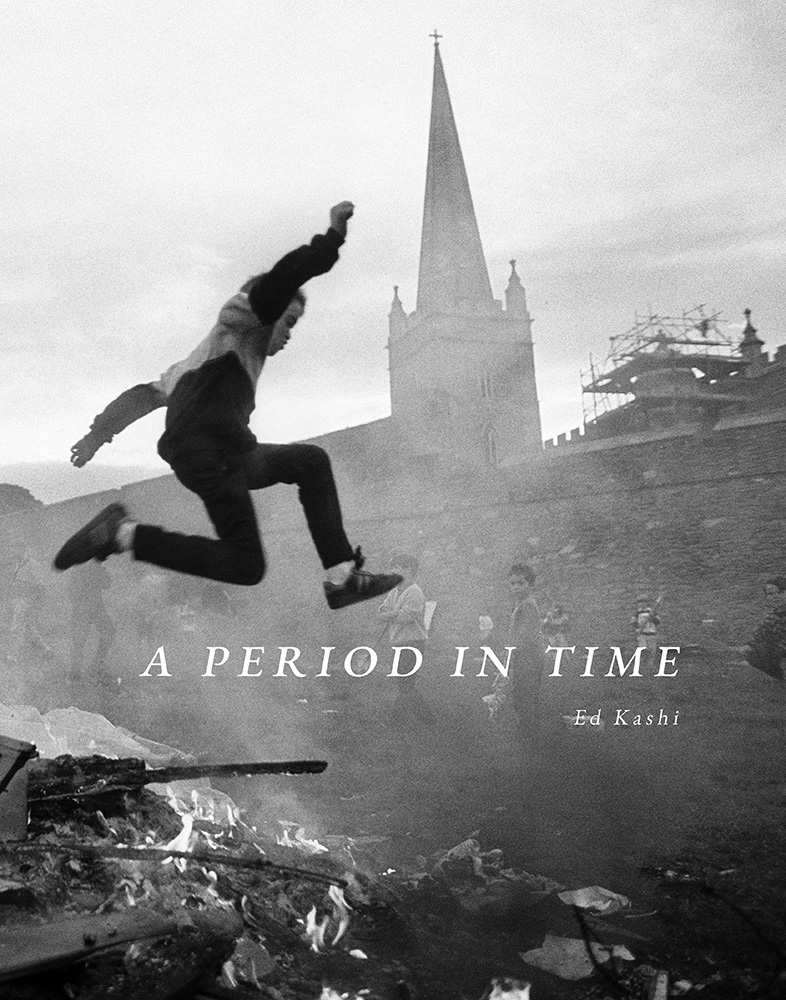

In the image on the cover of photojournalist Ed Kashi’s latest book, A Period In Time: Looking Back While Moving Forward, 1977-2022, a boy soars over a bonfire, seeming to float next to a ghostly church steeple. The image crackles with energy as it toggles between anticipation and anxiety, exuberance and danger.

The photograph was taken in 1989. Kashi was working on his first long-term documentary project, an examination of the violent conflicts in Northern Ireland. But even if you know none of those facts, the image creates a mesmerizing narrative. It is an exceptional photograph because it is timeless and universal.

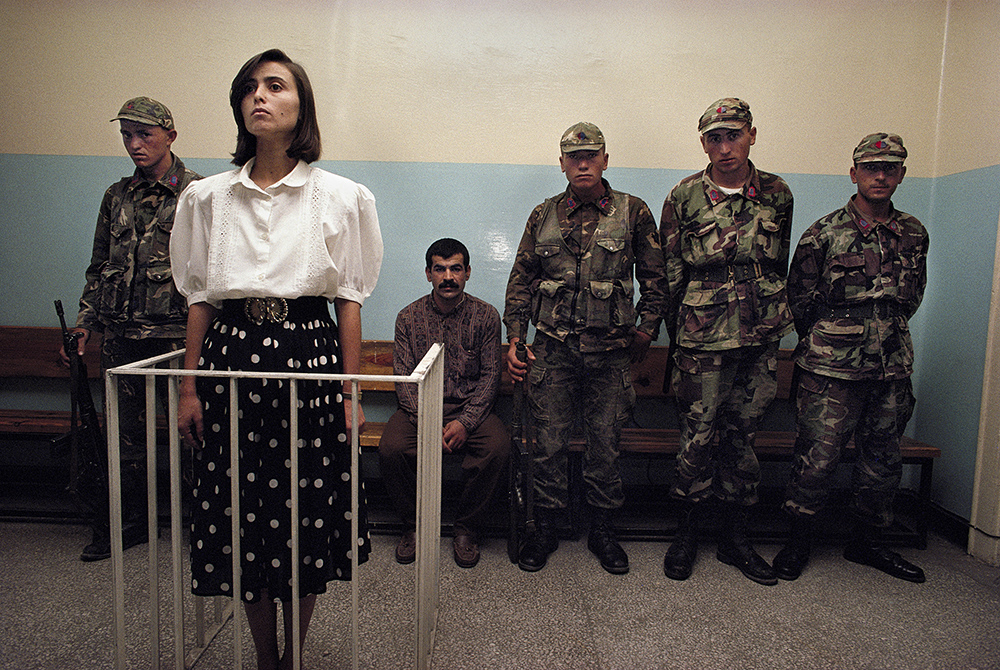

Kashi’s book, a retrospective of his 45-year career, contains more than 200 photographs taken from 1977 – 2022. With sensitivity and courage, Kashi has documented important events around the globe, including the struggles of the Kurds, the economic resurgence of Vietnam, the City of the Dead in Cairo, Arab Christians and the impact of the oil industry in Nigeria. He worked in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and other parts of the Middle East. He says his work in the Middle East opened his eyes to his family’s history. His parents were born in Iraq and immigrated to New York in 1940.

©Ed Kashi, A Kurdish woman stands trial accused of being a member of the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, in Diyarbakir, Turkey, September 16, 1991

Although most of his projects were overseas, he spent 8 years working with his wife and collaborator Julie Winokur on “Aging in America,” a fascinating look at what it means to have a “good old age.” The series includes many affecting photographs, including an image of the 90-year-old Maxine Peters as she lay dying. Family members circle around her, gently touching her and each other. It was beautiful, quiet and respectful.

© Ed Kashi, Maxine Peters died under the best possible circumstances—surrounded by family and friends at home in Gladesville, West Virginia, 2000.

Kashi describes his style as “candid intimacy.” He says his goal is “to disappear, to observe without disturbing the world I am trying to record.” There is no in-your-face sensationalism. The magic is accomplished in more subtle ways.

© Ed Kashi, A one-kilometer bridge being built over the Ganges River in Muratganj, India in 2007 has altered the life of the local people. Local farmers, water buffalo, fishermen, and local boats all exist under this modern, massive bridge that extends over this sacred river.

His images are complex, able to connect emotionally and still give people their privacy. Through creative framing of the scenes, he produces photographs that reinforce moods critical for the narrative – for instance fragility or danger or power. When the U.S. Army occupied the former palace of Uday Hussein, son of former Iraq President Saddam Hussein, and U.S. soldiers jumped into the pool, Kashi’s image was a memorable theatrical tableau that captured both the exhilaration of the soldiers and the weirdness of the whole scene.

© Ed Kashi, Soldiers of the United States Army’s First Armored Brigade occupy a former palace of Uday Hussein and swim in his pool.

Another intriguing image is of a 14-year-old boy in Nigeria carrying a freshly killed goat on his head. The light is gorgeous, but the sky is filled with somewhat ominous dark smoke. The boy’s face is solemn. The goat was roasted by the flames of burning tires. The photograph is part of a two-year project on the harsh economic and environmental costs of oil exploitation in Nigeria.

© Ed Kashi, A fourteen-year-old boy transports the carcass of a freshly killed goat, which has been roasted by the flames of burning tires at Trans Amadi Slaughter in Nigeria, 2006.

In his introduction, Kashi writes that he was “exposed to pain, suffering, violence, and death,” and in later passages – excerpts of emails to his wife – you can see him struggling with his desire to tell the world what is going on and his desire to protect those he is photographing

In a 1997 note to his wife, that he sent from Lahore, Pakistan, he wrote:

It was a tough day for me. I finally had a breakthrough on one aspect of this story I was determined to show – the epidemic of burned women…. Today, the family of one of the victims allowed me to talk with her and she said it was ok to photograph her. It was a harrowing experience. Her husband had thrown acid on her face, leaving an open and bloody sore. I was holding back tears while trying to work. These situations are so damned hard… Knowing I could make an image that will shed light on this important issue is inspiring. But then another part of me feels like shit for putting her through this process when I can see she is in extreme agony. I was able to photograph her in her bed, and while we couldn’t verbally communicate, I felt her permission and desire to have her story told.

When I returned to my hotel room tonight I had to share this with you. I wish we were close right now.

An interview with the artist follows:

© Ed Kashi, Badly burned, a woman awaits plastic surgery at a Lahore hospital after her husband allegedly threw acid on her face,1998.

Ed Kashi is a photojournalist, filmmaker, speaker and educator who has been making images and telling stories for over 40 years. Kashi has produced a number of influential short films and earned recognition by the POYi Awards as 2015’s Multimedia Photographer of the Year. Kashi’s embrace of technology has led to social media projects for clients including National Geographic, The New Yorker, and MSNBC. Along with numerous awards from World Press Photo, POYi, CommArts and American Photography, Kashi’s images have been published and exhibited worldwide. His editorial assignments and personal projects have generated fourteen books. In 2002, Kashi in partnership with his wife, writer + filmmaker Julie Winokur, founded Talking Eyes Media. The non-profit company has produced numerous award-winning short films, exhibits, books, and multimedia pieces that explore significant social issues. Kashi is represented by Monroe Gallery, located in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Instagram: @edkashi

X: @edkashi

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/edkashi/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/edkashiphotography

Threads: @edkashi

Bluesky: @edkashi.bksy.social

Sandy Sugawara: Congratulations on your retrospective book. It’s moving and important on so many levels, so I have several questions.

First, I’d love to know the story behind the cover photograph, the one taken in Northern Ireland.

© Ed Kashi, Children play around an impromptu bonfire in The Fountain, a Loyalist housing estate in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, August 11, 1989.

Ed Kashi: That image was made in what I consider the early days of my journey as a documentarian. I was young, naïve, excited and fully engaged in the process of a long-term, in-depth project. It was my first major personal project. I spent three years documenting the Protestant community of Northern Ireland, immersing myself in their culture, daily lives and traditions. On this night, I was hanging out with protestant youth in the city of Londonderry, or for Catholics, Derry. It was during the summer “marching season” where mainly working-class protestant communities set up bonfire sites and marched in the streets. The scene unfolded quite organically and represents what it means to gain access, acceptance and blend into the background to capture candid moments. This was during my analog days, so using film and a Leica camera. No autowinder or massive multiple frames, just using my judgment, reflexes and timing to capture a moment that was fleeting.

© Ed Kashi, Maxine Peters, 90, on her deathbed surrounded by Arden, her husband of seventy years, along with family, friends, and caregivers, Gladesville, West Virginia, 2000.

SS: I’d also like to know more about Maxine Peters, the 90-year-old woman you photographed as she was dying. I saw the contact sheet and your comments about what unfolded while you were there. Can you describe the scene, and how you came to be there.

EK: This image and the backstory is one of the most important and powerful personal experiences I’ve had. There was no war, guns, conflict, or hyper drama. It was about a deeply intimate, universal and timeless experience. I had spent time with the Peters’ at their rural farmhouse in West Virginia the previous summer, where we got to know them and learn about their situation. Maxine and Arden Peters were 90 and had been married for 70 years. Warren, 76, a friend they made during their daily visits to a local Walmart, had moved in with them to help Arden take care of Maxine. I had returned to be with them during a family reunion, living in the house with them, when on this day it was clear Maxine, who was suffering from end stage Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, was meant to pass. She was clearly a very strong woman, but she needed to allow herself to let go. I’ll never forget this. The folks in the house asked me to tell Arden that it was time for him to go into Maxine’s room and let her know it was ok to release. I don’t know why they chose me, and as you can imagine it was a tremendous honor and sign of trust that I had built with them, but also an overwhelming responsibility. It is a reminder that in this work we sometimes must wear multiple hats. Yes, we are documentarians and need to keep a certain distance, but we are also humans and have a responsibility to respect and honor those who have granted us this sacred entre into their lives. So I went to Arden, on bended knee, and suggested he go to Maxine and speak to her. He did so and two hours later I made this image as she was taking her last breathe. A few days later at her memorial service at their local church they also asked me to speak.

©Ed Kashi, The Stations of the Cross procession for Catholic Easter in the Old City of Jerusalem, 2008. The women holding the cross are Arab Catholic Scouts.

SS: Most of your projects have been overseas. Why is that?

EK: That’s an interesting question. I guess I’m a lifelong learner and while America is crucially important to me and I’ve done one of my major projects in America and am currently working on a long-term book project about America at this moment, I’ve always been drawn to other cultures and places. My parents immigrated from Baghdad in 1946 to NYC and sometimes I think there is an unconscious part of me that is deeply connected to other cultures. There is also the journalist and anthropologist in me that desires to use visual storytelling to learn about the world and report on it. And I love to travel and meet people where they are. Growing up in America has been a privilege and, in some ways, allowed me to feel empowered to use that privilege to explore the world. I also feel impassioned that Americans need to open their eyes to the rest of the world to understand what we have here, however imperfect it is, and the importance of broadening and learning from other cultures.

© Ed Kashi, Young schoolgirls dressed in the traditional Ao Da in Saigon, Vietnam, 1994. Pre-communist fashions have made a big comeback since the late 1980s, when the government began to loosen restrictions on clothing.

SS: In the introduction, you wrote about learning about the world by leafing through Life Magazine. I think that is true for many people of our generation. Is there an equivalent venue or platform today for excellent photojournalism to inform and connect the world? Has the consolidation and shrinking of the media industry impacted the life of photojournalists?

EK: That’s in interesting question. In some ways National Geographic magazine and it’s digital and online iterations serves that purpose, but for me NatGeo was always too wedded to storytelling that was not political enough and now more than ever is more focused on the natural world, which is a great thing! Funnily enough, Instagram and other social media might be filling that role today, which is a frightening thought, given the lack of control and with AI and chatbots, the lack of veracity in so much of what we see on these platforms. While in the days of Life magazine there wasn’t much else to expose you to the world, as TV was in its early days, now we have an overload of global information. This is why we need media literacy to be taught, starting in middle school. As for the life of photojournalists, it’s never been easy but now it’s harder than ever to make a living and to get your work out there. Social media has become incredibly important, for better and worse. In the end of the day, if you have a great idea and execute on it well, you can find a place in our fractured and fragmented media landscape. Making vidoes has also become an essential part of the photojournalists world unless you’re one of a handful of folks who can command the few remaining spots in the editorial landscape.

©Ed Kashi, Settlers perform ritual ablutions in an ancient spring near their village in West Bank occupied territories, 1994. Because this spring was once used by local Palestinians, security is tight.

SS: I was so happy to hear that your archive will be housed at the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. It’s important that key photojournalism collections be preserved because they are an important part of history and they provide critical context. With the faltering finances of media companies, it is sometime unclear what will happen to some important photography archives. Can you tell us how your relationship with Briscoe came about?

EK: I had reached out to Don Carleton, the Founder and Executive Director of the Briscoe Center a few years ago when my last book, Abandoned Moments, came out. He responded by telling me that he only exhibited photographers he collected, so I asked him how one gets collected and he thankfully responded by saying he’d be honored to collect my archives. From there the relationship took off and resulted in my donation last year and now subsequent book, A Period in Time. I felt it was time to think about my legacy and find a permanent place for my archives. While I’m still producing new work, I also was feeling the physical responsibilities of maintaining my archive were becoming an albatross around my neck. I’m honored to be a part of the Briscoe Center and it’s rewarding to realize that all the hard work, investment in staffing and infrastructure over the past 45 years has resulted in this beautiful outcome.

© Ed Kashi, Scenes of refugee youths on a farm in the middle of the desert between the Syrian and Iraqi borders in Ereinbeh, Jordan, 2013. The siblings have been in Jordan since August 2012, having fled to avoid rape of the girls and conscription of the boy into the military.

SS: When you travel overseas, what kind of camera lens and other equipment do you take with you?

EK: In the past during my analog days it was a combination of Canons and Leicas. Now I’m only a Canon user, for both still and video. My favorate lenses are the 50mm 1.2 and the 24-70 zoom. I like to work light so I can be fleet footed and mobile, and also to save my body!

© Ed Kashi, A 67-year-old sugarcane worker in Chichigalpa, Nicaragua, photographed on April 25, 2014. After twenty-five years working in these sugarcane fields, he developed chronic kidney disease of nontraditional causes (CKDnT).

SS: What’s Next? You have talked about the importance of “advocacy” journalism and about the power of still images to change people’s minds. Are there subjects you would like to tackle next? What subjects are ripe for advocacy journalism?

EK: Right now I’m focusing in my personal work and my grant proposals on the impact of heat stress on manual laborers around the world, including America. This issue has grown out of my more than a decade of work on chronic kidney disease globally. I feel it’s an issue that is pressing, that we need to know more about and bring to light and that I am well positioned to speak about.

Book Specs:

A PERIOD IN TIME

Dolph Briscoe Center for

American History

11 x 14 inches, 344 pages, 235 color

and b&w photos

ISBN 978-1-953480-22-4

Upcoming book signing:

Jan 28 – University of Texas at Austin. Co-presented by The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History and Austin Photo Night.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026