Photographers on Photographers: Emily Wiethorn and Morganna Magee

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with Emily Wiethorn‘s interview with Morganna Magee. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

Morganna Magee is one of those people you meet through social media and immediately feel close to in some way. Her work struck me straightaway because of the vulnerability and rawness of her subjects in her body of work Teenage Wildlife. Ego Eimai stayed with me specifically because I also employ my mother as a subject in my work and am always fascinated with photographers that dare to dive deeply into those complicated relationships. The way Morganna has captured her mother with so much honesty, curiosity, and respect is astounding and admirable. Ego Eimai is nuanced, thoughtful, and complex, and I feel so lucky to have had the opportunity to work with her in on this interview.

Morganna Magee is an Australian social documentary photographer and educator based in Melbourne,Victoria. Morganna’s work centres around long term projects in which the relationship between photographer and subject challenge the traditional notion of the impartial gaze of the photographer. To date her personal work has explored the issues and complexities around disability, grief and womanhood. Morganna is a founding member of Lumina Collective. Her images have appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Age, The Big Issue, The Weekend Australian magazine, Art and Australia magazine, Broadly,com, Wooden toy Quarterly, Lostateminor, and Black and White Magazine. She has photographed major commissions for Wintringham Specialist aged care, the shire of Murrundindi, Victoria Police, the Mission for Seafarers, Ronald McDonald House and The Immerse Arts Festival among others. Morganna lectures in Photo Imaging at Swinburne University of Technology.

Morganna Magee is an Australian social documentary photographer and educator based in Melbourne,Victoria. Morganna’s work centres around long term projects in which the relationship between photographer and subject challenge the traditional notion of the impartial gaze of the photographer. To date her personal work has explored the issues and complexities around disability, grief and womanhood. Morganna is a founding member of Lumina Collective. Her images have appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Age, The Big Issue, The Weekend Australian magazine, Art and Australia magazine, Broadly,com, Wooden toy Quarterly, Lostateminor, and Black and White Magazine. She has photographed major commissions for Wintringham Specialist aged care, the shire of Murrundindi, Victoria Police, the Mission for Seafarers, Ronald McDonald House and The Immerse Arts Festival among others. Morganna lectures in Photo Imaging at Swinburne University of Technology.

Emily Wiethorn: Could you introduce yourself a little bit and give us some background on what lead you to making Ego Eimai?

Morganna Magee: I’m a photographer working in Melbourne Australia. After a short but eye opening career in photojournalism, my practice now centres around portraiture and long form storytelling. My way of working always involved photographing strangers. I develop intense friendships with the people I photograph but it always starts with a cold call. I’ve never quite believed the level of intimacy strangers will allow me- I think it’s been a big part of why I worked the same way for so long, that disbelief that I’d be able to continue to do it. I started Ego Eimai while I was photographing for another series and had become bored of what I was making. My relationship with my family has always been strained; I have always felt discomfort around them. The work began with a portrait of my mother; I had wanted to photograph her but had never had the courage to ask. Photographing her was such a different experience to the portraits I usually make- I couldn’t employ any of my usual tricks to make her feel comfortable as she saw straight through them.

EW: What role does memory play in this body of work? Both yours and your mothers.

MM: The inconsistency of memory has become central to this work. Memory shapes our identity but I don’t know that any of us are such reliable witnesses to our own lives. My mother’s memories of Cyprus became my memories as they were passed down to me, as did traumatic moments in my early life that I don’t have clear memories of. When I was 2 I almost died of drowning, a trauma that still haunts my mother and a seminal moment in her life. But I don’t remember it despite it happening to me and I have no fear connected to it. I find it so fascinating we can be both player and spectator in such seminal moments in out lives. For my mother, Cyprus became a defining part of her identity that was mythologised. She left at 4 and has never been back yet those memories have become central to who she is and through her, important to who I am.

EW: As women, our relationship with our mothers is complicated, what has been your mother’s reaction to this series? Have their been any difficult moments? Could you elaborate?

MM: The complicated nature of that relationship is what scared me from making this work for a long time. For documentary photographers the relationships we have with the people we photograph are so important and framed by ethical and moral boundaries. To make work about my mother with whom my relationship was strained seemed a risk. The first image I took of my mother she has told me she hated. That was hard to hear. And I had wanted the work to encapsulate my mothers siblings but enquiring into the family history caused fractures that have not yet been repaired. Strangely though I’ve not thought about stopping photographing – I think the limits usually applied to my work don’t exist here. Maybe having that tension in the past made me more immune to the fear of causing more through making this work, I don’t know that photographing could cause more damage.

EW: How did you approach this work from a photographic standpoint? What visual elements became important to include?

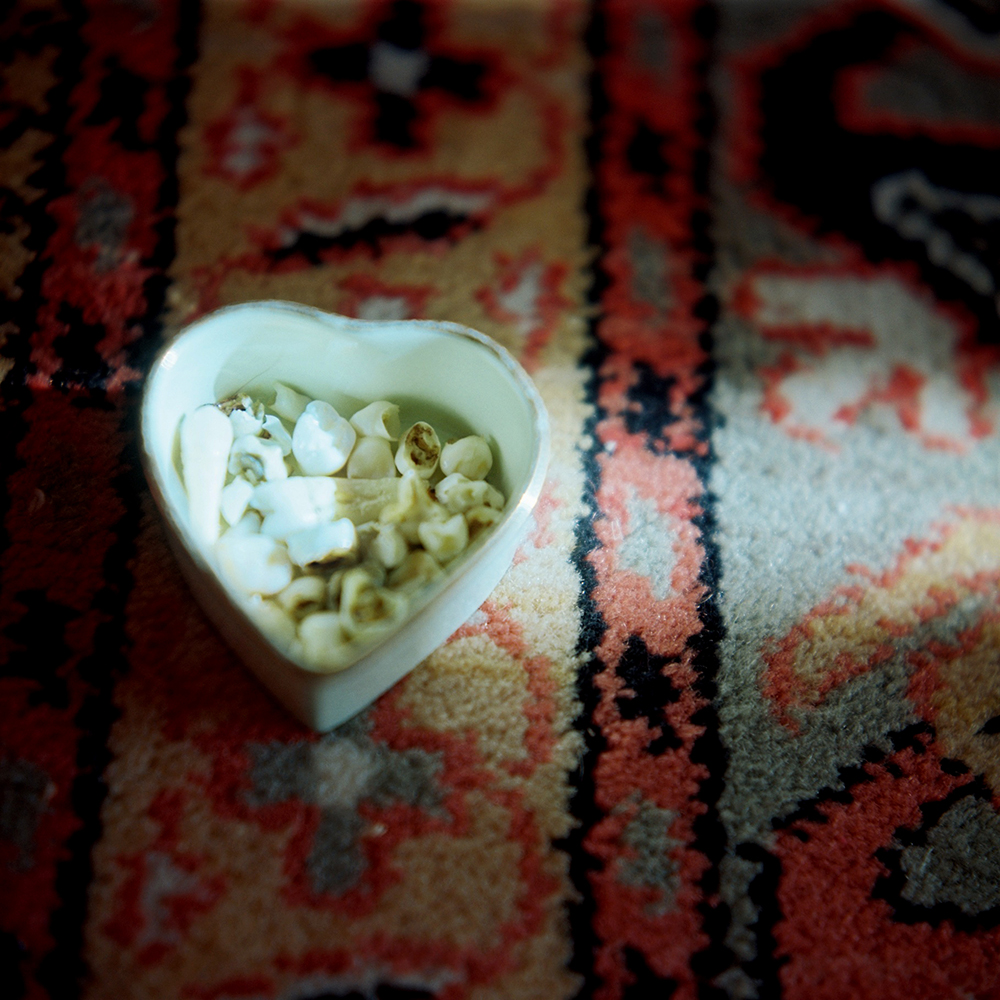

MM: It can be difficult photographing portraits, as so often the sitter feels obliged to give you what they think you want. This is amplified when it’s your parent. I could not catch my mother off guard and gave up trying to early on. Instead I felt like I could treat her like a model, directing her and, depending on the day, collaborating with her to make the images. The still lives were a complete change in the way I work- my supervisor really encouraged me to persist with them and I found that light was so transformative in creating the images that had some sort of resonance.

EW: I was wondering if you could talk about growing up with immigrant parents, how has that affected your identity as an artist/person?

MM: Being a child of immigrants in Australia in the 1980’s was interesting. As my parents were both European I was spared a lot of the racism the kids from Asian parents dealt with however it was made clear to me that I was different. It’s an interesting thing Australia is a country with an uncomfortable relationship with it’s own history and, especially where I grew up, if you weren’t Anglo Saxon it was assumed you were from somewhere else, the ‘other’. I pushed back against this identity for a long time, always facetiously answering questions around my race and “ where I was from”. I have no link to my Cypriot heritage, I don’t speak the language, we were never encouraged to join the community here. And for my Dad who came here at 17, his identity as an Irishman was core as he felt an outsider in this country. I guess that is the inheritance I have taken from being a child of immigrants in Australia, always slightly on the out, having to work just a bit harder to fit in. This has most certainly infiltrated my practice as an artist, I think to do the sort of work we do you need to be a chameleon.

EW: What inspires and motivates you in your daily life?

MM: I teach photography for a living so am extraordinarily lucky to be able to look at images all day long which I think is the best motivation to make work of your own. Part of being a photographer is being sentimental I believe to- we are all trying to hold onto moment’s real or imagined. As I’ve gotten older that compulsion to have images, to collect memories has become stronger.

I am also fortunate to be in a collective with 7 other Australian artists called Lumina who constantly inspire and motivate me to be a better artist. Communities of practice are very important to me, one of the benefits of the socially connected world we live in is the ability to reach out and to see how other artists are working.

EW: How has making this work with your mother impacted your view of her outside of the matrilineal relationship you share together?

MM: I can say with absolute certainty it’s changed our relationship completely. The heaviness of our interactions lifted through the act of photographing which as we know can often be kind of ridiculous. It was during s meeting with my supervisor that I realized the portraits of my mother showed me falling in love with her. To be able to do so at my age when parental mortality becomes an uncomfortable reality is nothing short of amazing.

EW: In your opinion, what artists are making exciting work currently?

MM: The beautiful thing about Instagram is that you can be visually stimulated all day long and be introduced to artists you may never have interacted with before. Emily, you are certainly one of these artists as are Aneta Bartos, Ionna Sakellaraki and Sergey Nazarov to name a few.

In Australia artist Emmaline Zanelli’s work blows my mind as does the work of my supervisor Kelly Hussey-Smith.

EW: Could you elaborate on your artistic practice a bit for us? What does your process look like?

MM: It’s ever changing and I have to say undertaking a formal study program has shifted it a bit. I work super intuitively, the core of what I do is connecting with people but the MA has slowed my process down a little which means I have time to contemplate and research. I also think having time to think. And time to percolate ideas is invaluable to me now, even this work has now evolved to encompass my childhood memories and the unphotographed little moments that are central to identity.

EW: What’s next for you? Is there anything you’re currently working on that you’re excited about?

MM: I’m getting ready to show a series I have been working on for 5 years in my home town of Melbourne. It’s a very different series focusing on teenage girls. I’m also in my final year of my masters and expanding this series to become more about my family as a whole and the way the act of narration forces a reassembly of fact.

Emily Wiethorn is an artist and educator based in Cincinnati, OH. She received her MFA in Studio Art from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and her BFA in Photography from Northern Kentucky University. Recently, Emily was the featured cover artist in PDNedu’s “The Fine Art Issue” (Spring 2018), a 2017 SPE Student Award for Innovations in Imaging winner, and a 2017 Critical Mass finalist. She was a graduate student presenter at the 2018 SPE National Conference in Philadelphia, PA and panelist at the MWSPE Chapter Conference in Lexington, KY. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, as well as featured online by Vogue Italia, PDNedu, Lenscratch, Musee Magazine, and PHOTO–EMPHASIS. Through her work, she explores notions of feminine identity, societal constructs of femininity, and self-discovery. Currently, Emily teaches photography at Northern Kentucky University and the University of Cincinnati.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025