Greece Week: Ioanna Sakellaraki: The Truth is In The Soil

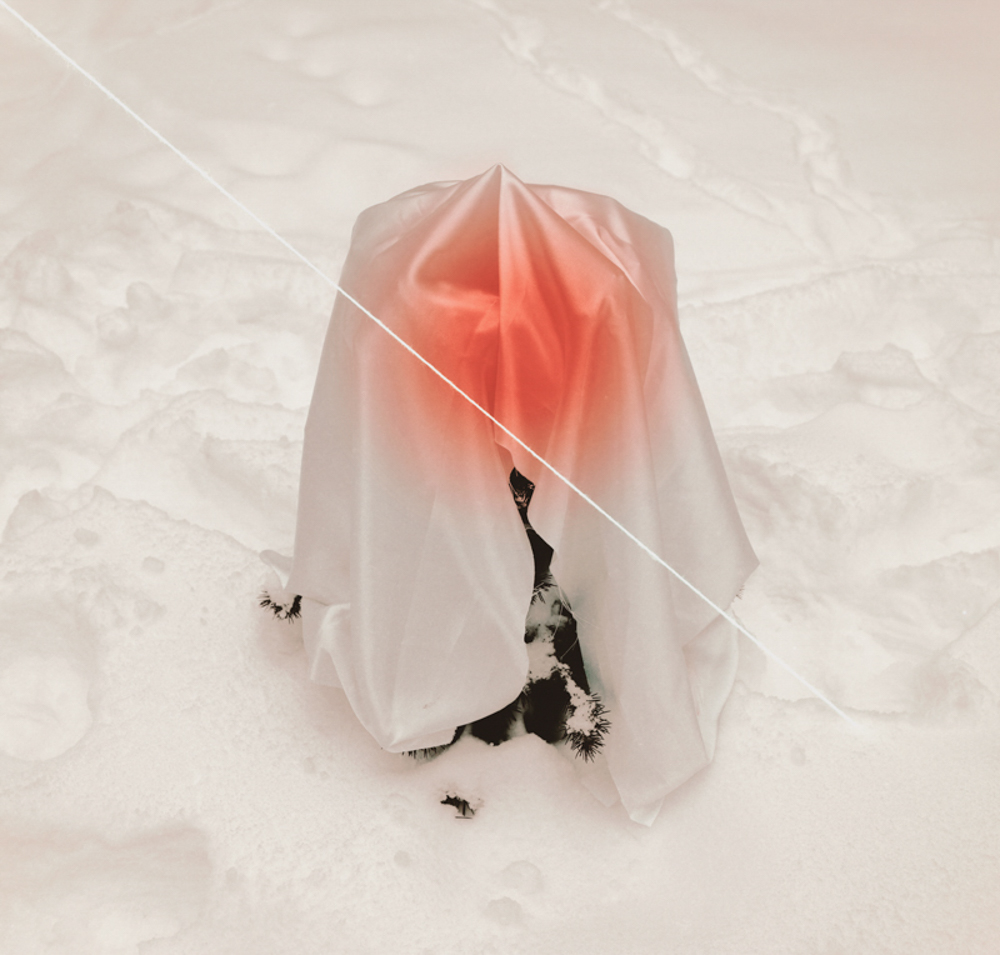

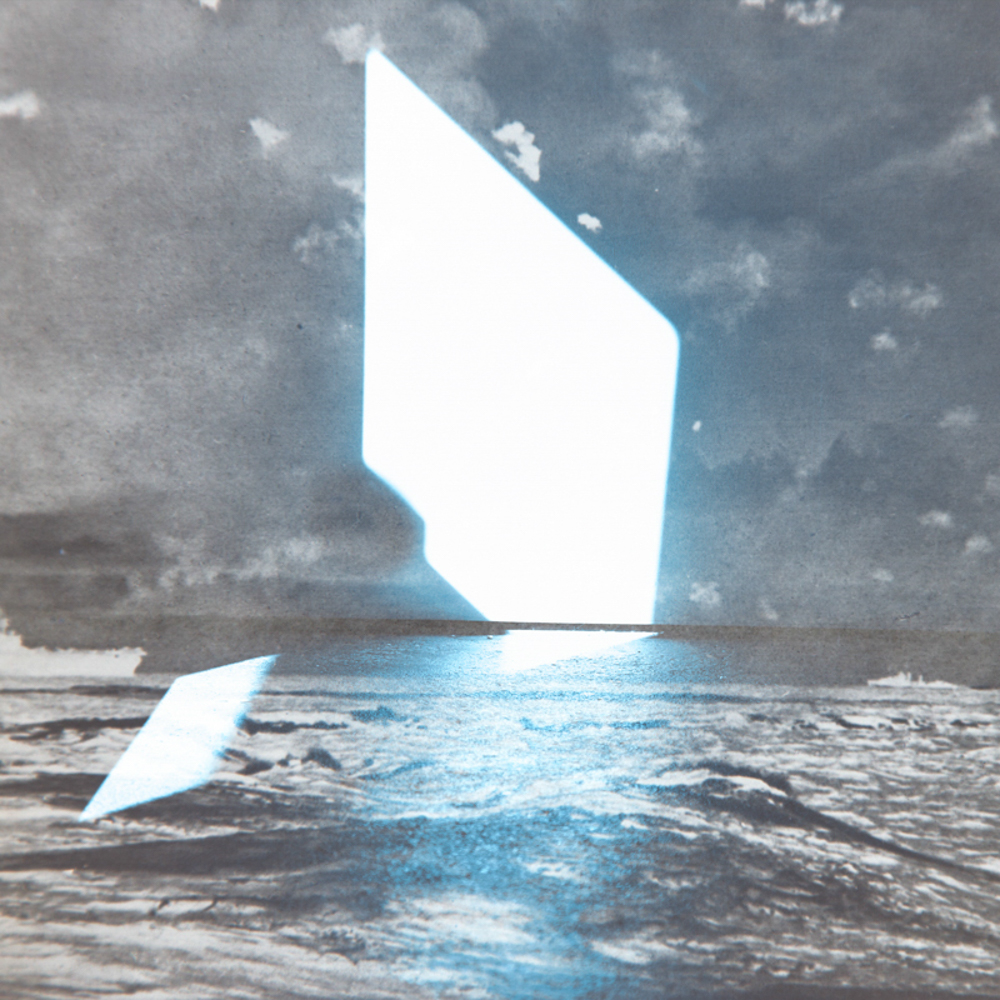

For Ioanna Sakellaraki, The Truth is in the Soil started with the loss of her father. But it in fact explores much wider topics of bereavement such as cultural grief rituals, absence and presence, what is real or not, complying or rejecting societal and familial expectations… For this project she visited the last remaining Greek professional mourners. She photographs with a medium format analog camera, then edits digitally to construct imagery that is both anchored in reality and navigating the unreal. The process in turn allows her to deal with personal tragedy while also examining and discovering her relationship with her family and her culture.

Born in 1989 in Athens, Ioanna Sakellaraki is a graduate of photography, journalism and culture. Her images suggest a constructed space of fantasy and loss within the magical potential of transformation and fiction the camera allows. Her ideas revolve around memory and loss and are strongly connected with her homeland Greece which has an archetypical aura and ambiguous personal importance. Her work was shortlisted for the Prix Levallois 2018 in France and Urbanautica Awards 2018. She was recently awarded with The Royal Photographic Society Postgraduate Bursary Award and nominated for the Inge Morath Award by Magnum Foundation, the Prix Voies Off in Arles and the BMW Art and Culture Residency in Paris. After obtaining an MA in European Urban and Cultural Studies, Ioanna currently completes an MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art in London. Next to her personal projects, she is a contributing photographer for London-based agency Millennium images and she also licenses part of her work to global media such as The Guardian, The Telegraph, Getty Images and others.

The Truth is in the Soil

After my father passed away three years ago, I returned to my homeland Greece and followed my mother’s behaviours as a believer seeking for shelter in the wider system of religious traditions and cultural beliefs in a society functioning on that basis. Photography transformed itself into a question of becoming through loss and made the passageway within a liminal space of absence and presence. As the project advanced and while inspired by the origins of ancient Greek laments, I dwelled within traditional communities of the last female professional mourners inhabiting the Mani peninsula of Greece looking for traces of bereavement and grief. My personal intention for realizing this project has been the impossible mourning of my father that is yet to come while making this body of work contemplating fabrications of grief in my culture and family. In a way, these images work as vehicles to mourn perished ideals of vitality, prosperity and belonging. By connecting my poignant grief with the dramatisations performed by the professional mourners, I look into the subjective spirituality of Greek death rituals. I am interested in how the image affirms things in their disappearance and gives us the power to use things in their absence through fiction. The photographs themselves lay between real and unreal allowing the viewer to believe in the real that is yet to come; another type of reality. – Ioanna Sakellaraki

Was there a photograph or a specific moment in time when you realized that the work you were making was going to be about much more than your own personal mourning? How is this body of work changing your relationship to grief?

I think I had this feeling from the very beginning of the project. It was like making images was becoming a tool at grief’s disposal. To that extend the image itself began to make things appear to me. I couldn’t see how to go through this personal loss as I have been following no religious principles and I was hardly part of my cultural traditions, but I could definitely have a clearer understanding of how my photographic practice was building a passageway through the process. Closer observations within my family and culture, were creating a space for images to emerge. Photographing my family and specifically my mother (during the project Aidos) was something new to me, as new as grief was, so I treated both in the same way. My mother became someone I tried to understand, this mourning figure that to some extend was also myself. The images were pushing me to not only encounter my relationship with my family but also my culture and country itself. Gradually, Greece was becoming that mourning figure, a land of curiosity where death was an encounter through family, religion, mythology and the self. They say death is sometimes the work of truth to the world, sometimes the perpetuity of something that does not tolerate either a beginning or an end. I feel that working around these subjects has made grief an encounter, an open-ended cultural enigma with both subjective and objective interpretations. So from there on, naturally, my perception and approach to my subjects has opened up to the world, like a space where the image finds its condition and disappears into it.

There are mythological references in several of your series, in this work too like with Persephone’s pomegranate – references that I do not have myself. Greek mythology is something I only read about in school books when I was 12 and I have therefore no idea of how much it permeates through every day contemporary culture in Greece. Do you incorporate it in your work because it is an inherent part of who you are as a Greek woman?

I asked a Dutch intern to comment on my selection of artists for this week. Despite the variety of subject matters and styles, her first reaction to the imagery was “They all look so very Greek…”. Do you think there is such a thing as “a photograph being very Greek”, and if so, what would that mean?

I try to go away from Greece while craving to connect with it. It always comes back to you. Greece is a heavy place, no matter how it is seen from the outside. And I think Greek people have it in their blood, they like heavy; the complexity and struggle of it. I mean that’s where tragedy originates from. All of the nation’s history is built on the notion of philosophy translating as the love of wisdom, the continuous reflection on fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. You are educated this way and along the way you are also encouraged to build a character where confrontation and debating are the usual everyday weapons of speech and self-expression. I think this is wonderful, is a fascinating place with so many facets to it but I do believe, and this goes for any nation with heavy ideology and cultural background, it is only when you step out of what you believe you know that you find your real identity. I think there is always place for the individual to build themselves anew, and there is always space for the image to occur, influenced, inspired, connected to an identity, but grown and able to stand outside of it, with the potential to talk to the world. It is like philosophy and history, which are heavily formed and grounded to their own ideals of a certain time and place but capable of carrying their notions through universal spectrums and identities because life, anger, love, death; they all have shared meaning. And to finally respond to the question, I wouldn’t know what a Greek image looks like. I have been told that most of my photographs hardly depict Greece as they look cold, dark and distant. I think it is good when you cannot give an image an identity. The image itself is a paradox between knowing and seeing. My influences vary a lot. It could be that I take inspiration from how in his poetic cinematic space, Sergey Parajanov uses symbols of the origin as his starting point; what is unknown to us but not completely foreign, to speak about death as an image towards inspiration or how writers like Maurice Blanchot use language as an image which operates as a paradoxical force eating away the visible. It is all interlinked building up an inspirational discourse as the image emerges.

You have lived abroad for quite a few years now and have a background in journalism. Several years ago, you shifted from documentary work (sometimes in other countries) to topics that strongly relate to Greek culture and memory, and you do that through more constructed images. Did your expatriation play a role in those changes of both focus and practice?

I have been living abroad for the last decade. I left Greece soon after I turned 18 and lived in about 7 different countries in Europe since then. Most of my choices were based on studies and work. I literally haven’t stopped studying and learning new things which has led to a continuous progression of interests and self-development. While photography was big part of my life, I had already graduated from Journalism and completed an MA on Urban and Cultural Studies and most importantly I had already built a career around that. Photography was never a hobby though, was all I was making time and space for until I made the choice to give more to it and paused all the rest around it. I would say that it needs time and lot of hard work and energy. It is not something that can sustain itself in the sidelines of one’s life, it has to become your life and it will definitely change you. At least it did with me. I have learnt to be more patient and resilient, more curious about the world around me and to be honest a lot more excited about life even if my subjects are in the darker side of it. The shift from documentary work to constructing a world inspired by the reality of it was again a step-by-step process. My photography started with a focus on memory and territory, architectural relics and identity in different parts of the world. It always felt like I was looking for home while being away from it. My series Turtles is built on that longing to inhabit, the distinction between the real and the imaginary and the disturbance between represented space and personality. So the idea of space remained there but started transforming itself into a more personal entity, I name it personal because I construct these spaces. And even in The truth is in the soil, death itself becomes a space, the human figures of the female mourners turn into the landscapes themselves, a space opening onto the outside, perhaps an amorphous entity of innerness obeying to its own laws. To a certain extent, this frees me of the time of here and now and the world as it is. My current work investigates the boundaries of alternate orphic worlds laying between sheltering something from death and establishing with death a relation of freedom. Greece is a constant inspiration and encounter in my projects, but the way is depicted is imagined. Is like this idea of the homeland being this place you know outside of memory. By having been there or going there. A never-ending process with the image as a guardian of becoming.

And finally, what’s next for you?

There are a few shows coming up this autumn. I will be showing The Truth is in the Soil during Les Rencontres de la photographie of Marrakech from 14-20 October, a collaboration with Festival Voices Off in Arles, where the work was shown during this summer. From 18-31 October the series will be exhibited during International Meetings of Photography in Plovdiv, Bulgaria and I am also very honoured to be giving a talk on 19 October at The Royal Photographic Society in Bristol in collaboration with The Martin Parr Foundation during BOP Photobook Festival. I was also happy to be the 20th Grantee of Reminders Photography Stronghold in Tokyo, Japan where the work will be exhibited during 2020, dates to be confirmed. This is my last year of MA Photography at the Royal College of London so I will be working hard towards the Degree Final Show and one of my main goals is to start paving the way for making a photobook out of this work by next year.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 3November 27th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 4November 27th, 2025

-

Nancy E. Rivera: No Present to RememberNovember 22nd, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Molly WakelingNovember 6th, 2025