Politics of the Kitchen: Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman

By Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman

This week we feature a scant spoonful of the vast topic of The Politics of the Kitchen— six days of posts by photographers working with food, followed by a selection of submissions.

Over the decades of our photographic collaboration, we repeatedly return to the topic of food and the kitchen. Wildly high expectations we confront in our practice are framed in John Ruskin’s words:

“Cookery means the knowledge of Medea and of Circe and of Helen and of the Queen of Sheba. It means the knowledge of all herbs and fruits and balms and spices, and all that is healing and sweet in the fields and groves and savory in meats. It means carefulness and inventiveness and willingness and readiness of appliances. It means the economy of your grandmothers and the science of the modern chemist; it means much testing and no wasting; it means English thoroughness and French art and Arabian hospitality; and, in fine, it means that you are to be perfectly and always ladies — loaf givers.”

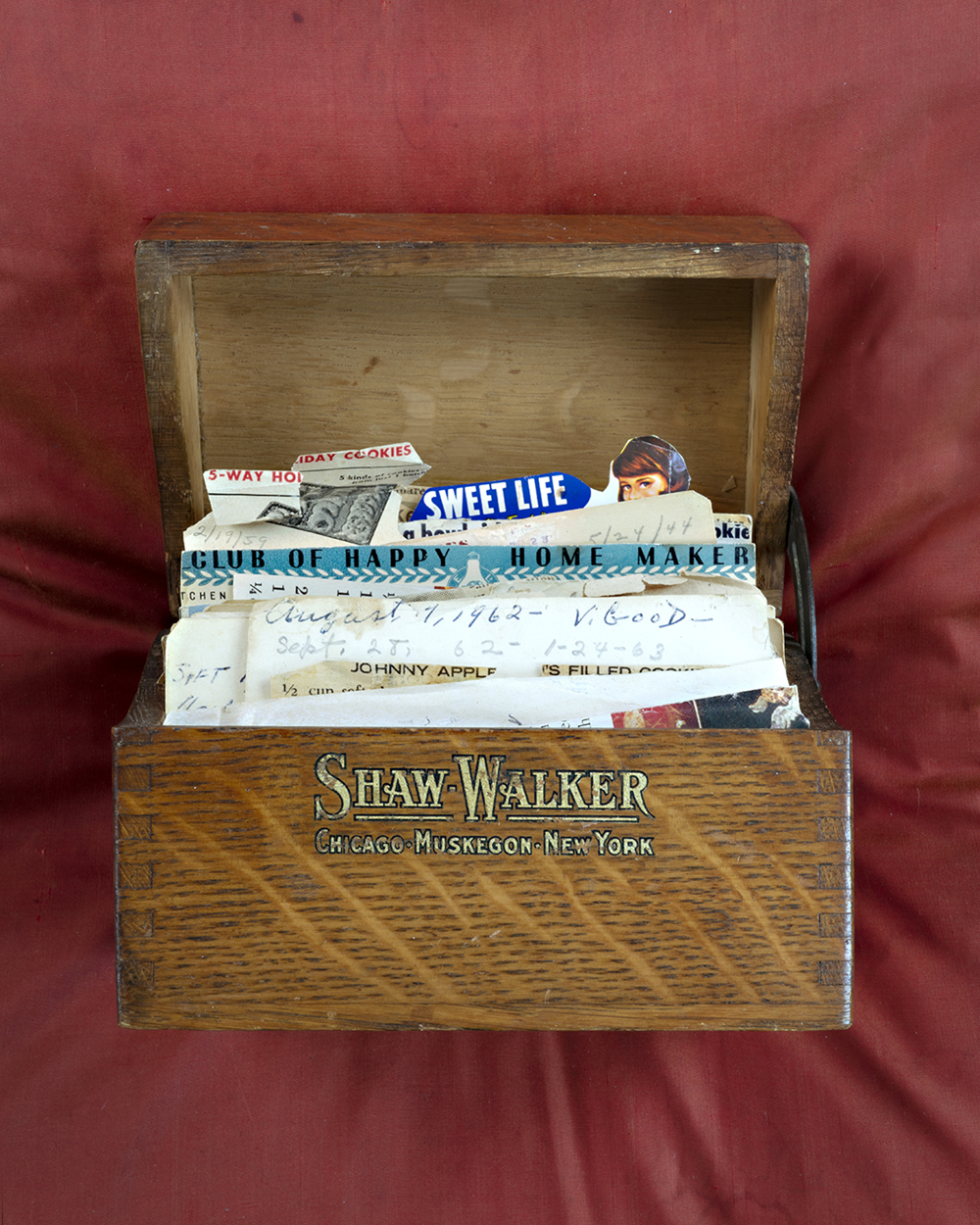

As second-wave feminists, we lived through a changing matrix of feeding and being fed — the acceleration of food marketing, diet fads, sexualized food advertising, the fraught landscapes of feeding our children. We’ve used food in our photographic work to critique domesticity, consumption and the climate crisis while reveling in its transformative potential. We rejected our mother’s recipes boxes and Betty Crocker cookbooks, but have found ourselves back in the kitchen during the pandemic, taking solace in baking sourdough bread.

It is said we are we what eat. In the physical sense of fueling and shaping our bodies, that much is true. When we approach the topic, we also consider if and when we eat, with whom and where, blending in who is doing the cooking. We concoct a cultural, political, sacred and profane stew.

Since its inception, photography has recorded an evolving relationship with food and the kitchen, interpreting sustenance and fueling desire. We recognize the depiction of food as a complex and coded language. The politics of the times are baked in.

As we introduce the week, we share a few morsels that have provided inspiration for our own work:

“In the summer of 1860 Fenton made his most deliberate and exacting photographs to date: a series of still lifes. Although the subject obviously had its roots in painting, his densely packed compositions are far removed from the renditions of everyday life by the Dutch masters. Instead, Fenton extravagantly piled luscious fruits and intricately patterned flowers on top of one another and pushed them to the front of his composition so that they seem almost ready to tumble out of the photograph into the viewer’s space. It is that very immediacy—the precarious composition, the lush sensuousness of the objects, and our knowledge of their imminent decay—that makes these photographs so striking.” —Wikimedia

The Latest Kinks in Canning (US 1917) Paramount – Bray Pictographs:From the George Eastman Museum

“One of the first purposes of the food commission newly appointed by President Wilson is to show the housewives the necessity of conserving. Every bit of food material that is wasted is just that much more food taken from the mouths of not only our men at the front, but of the millions of inhabitants of our allies. With that in mind, the Woman Suffrage Party of New York, as its share of war service is motoring through the farm districts to teach women in the scientific preservation of food; and their methods form a highly interesting and important subject to the seventy-sixth release of Paramount-Bray Pictograph.” – Moving Picture World (July 1917)

Semiotics of the Kitchen, Martha Rosler, 1975. ©2017 Martha Rosler

Rosler has said of the Semiotics of the Kitchen, “I was concerned with something like the notion of ‘language speaking the subject,’ and with the transformation of the woman herself into a sign in a system of signs that represent a system of food production, a system of harnessed subjectivity.”

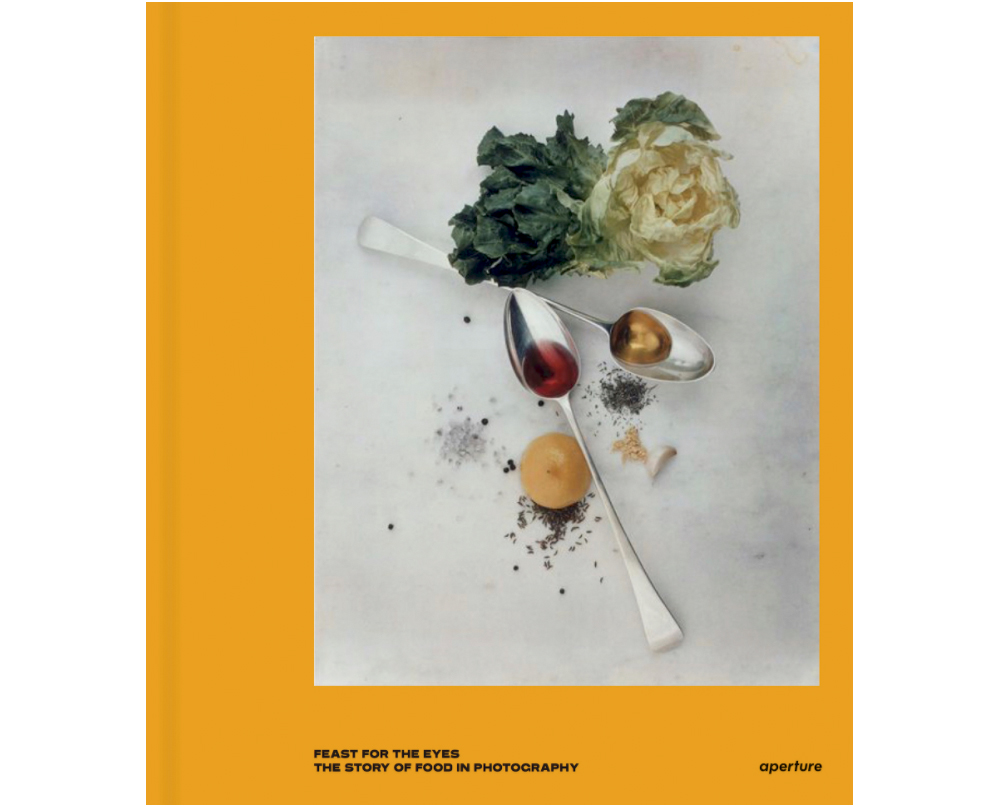

Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography, authored by Susan Bright, published by Aperture, provides an overview from cookbooks to art, fashion and advertising, in vernacular, industrial and editorial contexts. “Susan Bright’s introduction and commentary accompanying the photographs bring insight and intelligence to this spectacular subject, and trace the progression of the genre from photography’s beginnings to present day, featuring artists from all eras—Roger Fenton, Nickolas Muray, Edward Weston, Irving Penn, Stephen Shore, Laura Letinsky, Wolfgang Tillmans, Nobuyoshi Araki, and Martin Parr, to name a few. Through key pictures, Bright explores the important figures and movements of food photography to provide an essential primer.”

Personal favorites for food insights:

The Art of Eating by M.F.K. Fisher. The author says it all: “When I write about hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and warmth, and the love of it…and then the warmth and richness and fine reality of hunger satisfied.”

The Botany of Desire by Michael Pollan. An analysis of how people and domesticated plants have formed a similarly reciprocal relationship over eons.

Jell-O Girls by Allie Rowbottom. A memoir that braids the evolution of one of America’s most iconic branding campaigns with the tales of the women who lived behind its facade — told by the inheritor of their stories.

Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman are photographic collaborators. As an extension of their long-term examination of the domestic realm, their current work addresses climate change, consumption and connection through food.

Website: www.ciurejlochmanphoto.com

Instagram: @barbandlindsaycollaborate

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Hillerbrand+Magsamen: nothing is precious, everything is gameOctober 12th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025

-

Dodeca Meters: Arielle Rebek, Kareem Michael Worrell, and Lindsay BuchmanFebruary 7th, 2025