Photographers on Photographers: Cassandra Klos in Conversation with Linda Connor

Over the next two weeks, we are sharing some of our favorite Photographers on Photographers posts. Enjoy! – Aline Smithson

Like so many of us in the Photographers on Photographers series, I was first introduced to my interviewee, Linda Connor, while studying at school; the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston to be exact. Her name kept reappearing in my critiques, as I was troubleshooting how to shoot star trails with my large format camera, or sequencing my images to make a small book. Many of my mentors — Jim Dow, Bill Burke, and Sandra Stark (to name a few of many) — would show her work in class, example her sensitivity to poetic resonance, and remind me that envisioning our connection to the cosmos is not strictly a scientific endeavor but one steeped in a visual language worth exploring.

Her work has been in my visual memory ever since — what Linda would probably call my “constellation of artists.” A few years ago, I submitted to an exhibition to have my work juried by Linda, and while she did not know me or my work prior, she accepted it with a prize. Sometimes, when you feel like you’re in an artistic rut, or don’t know what to do next, a little encouragement from one of your photo heroes is all you need to keep your momentum going.

When approached by Lenscratch for this interview, I wanted to talk to someone who I not only enjoy their photographs, but someone whose career and trajectory I deeply respect. I am honored to have had the chance to speak with Linda about our overlapping interests in our visual history and culture, but also her career that spans decades, and what it’s like to be a woman who has continued to thrive through this often male-dominated and inequitable field.

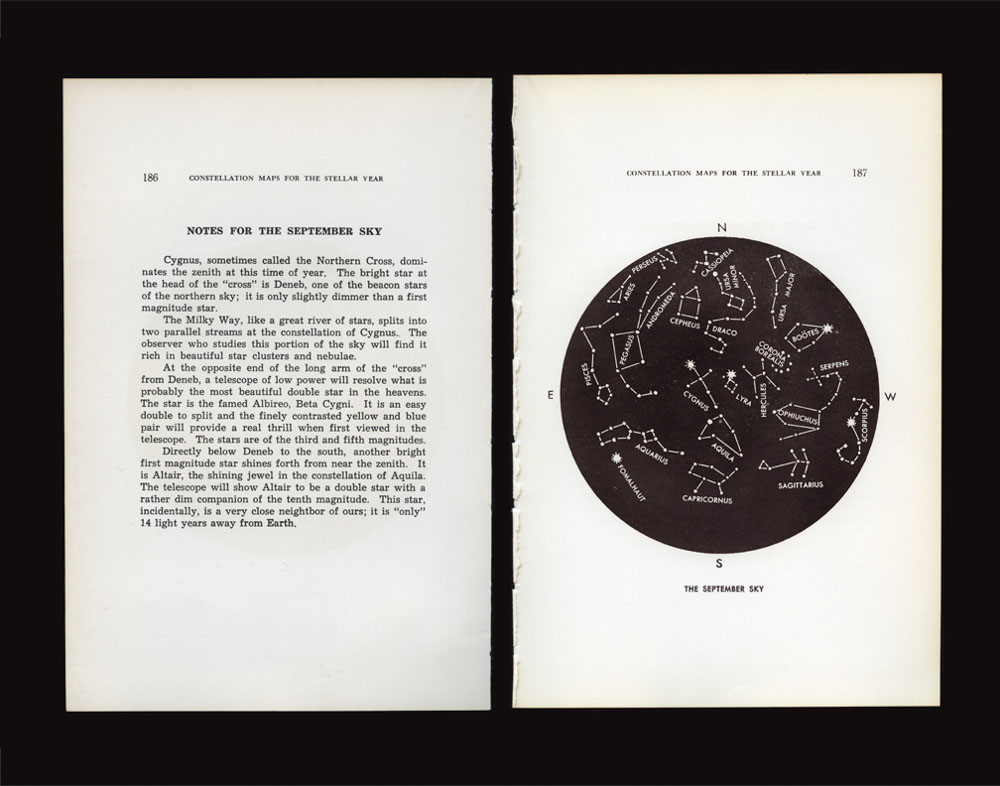

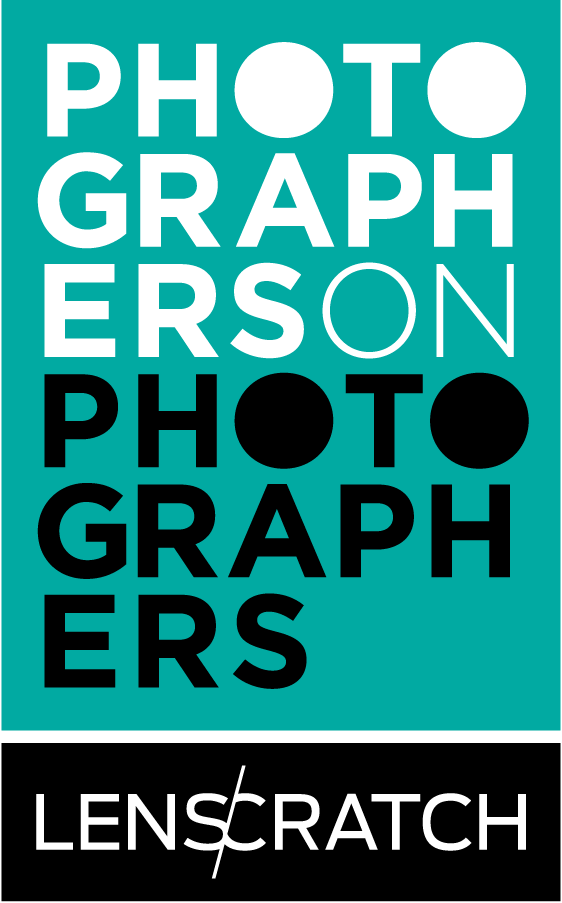

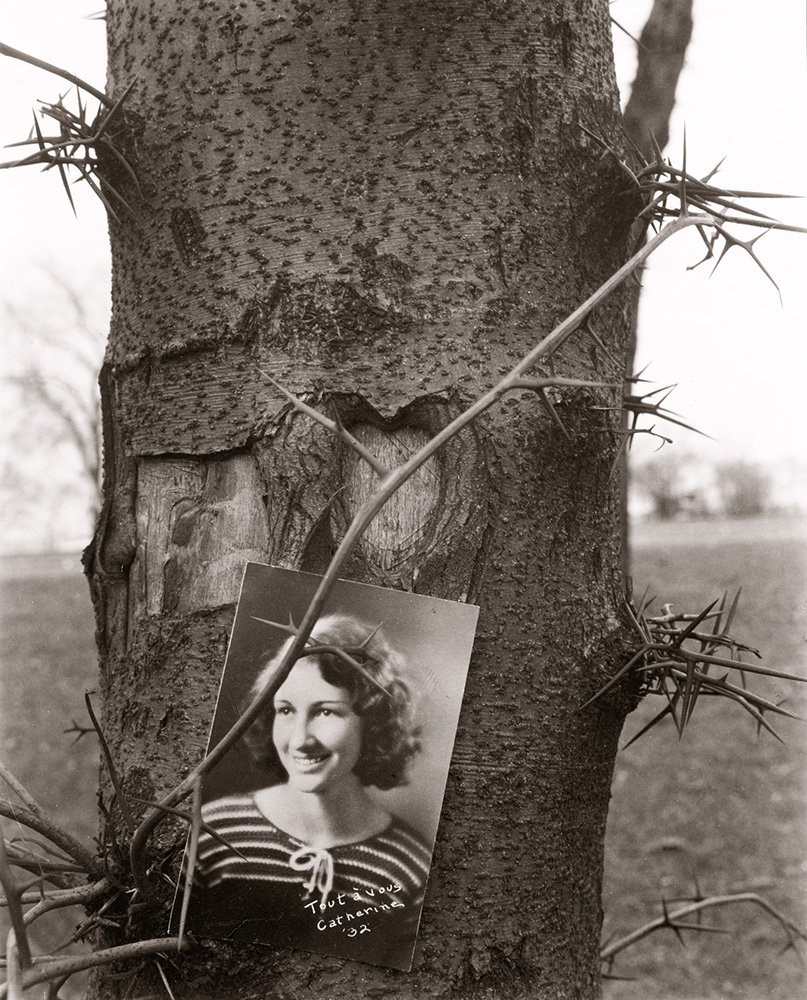

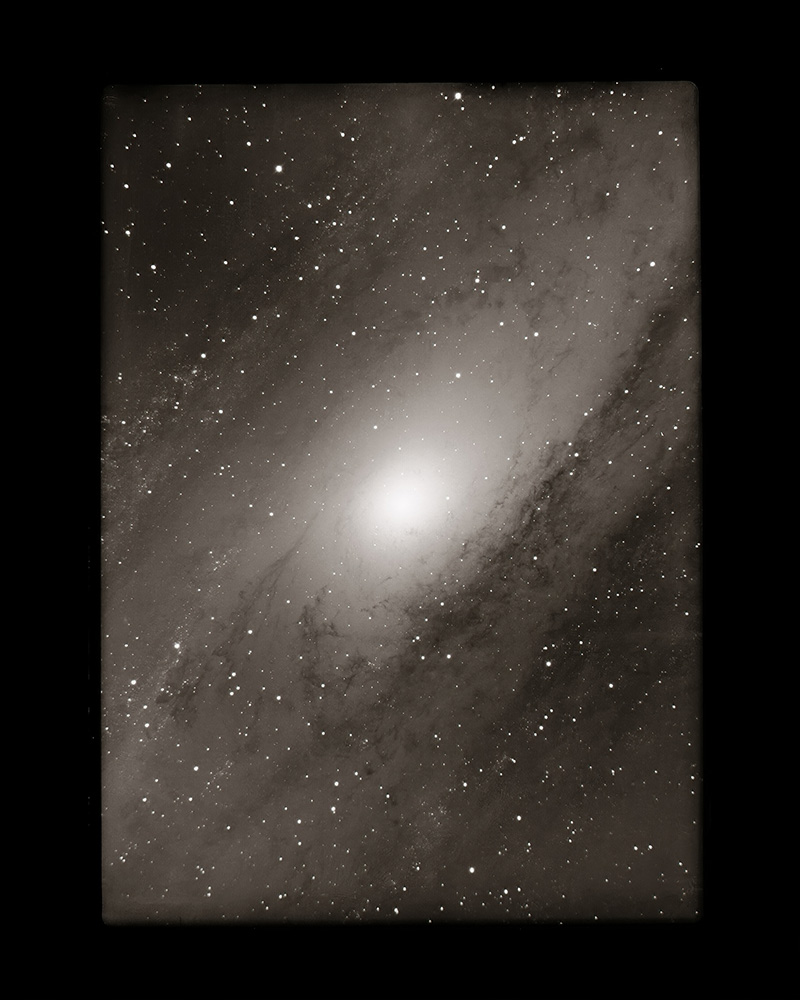

Linda Connor (b. 1944) is a photographer and dedicated educator who, for the last five decades, approaches both roles by enlisting the power of images—the ways in which they communicate, their unique properties, and how they interrelate. Connor embraces a wide range of subject matter, connecting the physical and the spiritual world. Just as sacred art evokes deep meaning without always an explicit understanding, Connor hopes her photographs serve a similar metaphorical function. Her photographs also capture elements of tradition in everyday life; such as the purposeful way people arrange their surroundings or the power of light to transform a space. Amongst her images are prints she has made from nineteenth-century astronomical glass plate negatives from the Lick Observatory archive. These images inspire contemplation of the spiritual and the scientific, culture and nature, and wonderment and knowledge.

She has exhibited nationally and internationally, published a number of monographs, including Odyssey: The Photographs of Linda Connor (2008), and is the recipient of many awards and grants, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and multiple grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, among others. In 2002, Connor founded PhotoAlliance, a driving force in the Bay Area’s photographic community—a community in which she encourages her students to participate. Her latest monograph is entitled Constellations (2021) and published by Datz Press.

Cassandra Klos: I’m curious what your biggest influence was in leaning towards the arts, because we all know it’s an affliction and not necessarily a choice. What drew you to the arts and becoming an artist?

Linda Connor: My two greatest interests were the natural sciences and art. And the nut of all that is that I couldn’t read. I’m dyslexic, but I wasn’t diagnosed as dyslexic until I was 30. I stayed back in the first grade and I couldn’t do math. I couldn’t do anything with systems.

When I finally got a camera when I was about seventeen, and it just sealed everything – that interest in observation, that interest in being out in nature. I didn’t get into the college of my choice, which was a good thing, because I got into RISD [Rhode Island School of Design]. But my dyslexia is still a handicap, there’s not a day that goes by now where I’m not literally swearing at [technology], and I’ve never been a particularly great technician with photography. It took me quite a while to figure out depth of field, because it made no sense to me that the bigger number was a smaller hole. You know, things like that. But the pictures… they’re indelible.

CK: You seem to be interested in a range of photographic approaches, from collage to documentary. How did you find your niche between these forms?

LC: Since I’ve been doing photography for about 60 years, there have been lots of opportunities for different approaches. Collage being one of them, landscape, images of people and ancient places. Though fashion has never been one of them. A great deal of my work has been done while traveling, whether in remote places in the United States, or international travel to places which have a rich ancient history. Later, when organizing the work, I don’t present it as anthropological, but rather, I tend to use the images more poetically. Even though, visually, the images are very true to their source. I have turned out not to be a documentary photographer.

Though, in my last year at RISD, I thought that would be my path. I think the sort of awareness of the deep connection with collage has happened more recently. But my interest in documentary stems from Walker Evans (my hero at the time) and RISD. RISD was a great place for me and the photo department was very strong. Emmitt Gowin was there at the time, and he was a very big, generous influence on everybody in the program. Most of the people who were doing serious work were grad students. I was still an undergrad. It was an all-boys club, but I still was very connected to them.

But Walker Evans was my guiding star, though if I had realized it, there was a constellation of influences that included Gowin, Julia Margaret Cameron, Harry Callahan, and others. What you wouldn’t necessarily get would be documentary, but kind of “altars” which were things that were presented in a kind of formal offering. If you think of an altar, that in a way is a still life of a collage of objects that are in a frame that is formal. Also, the view camera had a kind of intensity of description that I was interested in. It took me a number of years to figure out, but at a certain point your own work takes you there.

CK: I feel like a lot of your work gravitates towards documenting land and cultures which marks human presence – all through distinct use of metaphor. How do you feel like your use of metaphor, or your voice has developed over the years? I’m curious to know if you have felt like this has developed or changes throughout bodies of work?

LC: I was working on my final thesis, with Aaron Siskind in Chicago, and after a year and a half of collage work with collected photographs, I realized that my unconscious motivation was my own adoption, and not having a visual record of my family.

So for me, there was something about pictures and families that had such an unconscious power for me that I was collecting albums. At flea markets, I couldn’t believe that anybody would let go of those beautiful albums. And that realization, that unconsciously my own history was having an effect on my artwork was very powerful. And it was kind of like, “Okay you better learn to accept yourself and it’ll surprise you.”

I don’t find that I try to create metaphors. I find that I’m more apt to recognize them after they become evident in my work. If I’m at Angkor Wat with my 8×10, I’m really concentrating on how to make a good photograph. I’m not analyzing it at the same time, possibly later. It could be used in sequence of photographs where elements of symbolism or metaphor might be an underlying current to the content of the image. I like to think that my work honors what is before it. I rarely photograph out of anger or protest.

CK: Have discoveries about yourself continued to surprise you within your work?

LC: I don’t think of it too much now, in a way I think the work moves me along. But when you have a long career, yeah, you can try new things. But if they’re going to work at all, they really have to make sense for you. Just like in the beginning, you need to try a lot of things to see what fits best – and what other artists you want to be in your constellation. I rely a lot on what the images show me. They can recombine to lead into a new series or sequence, for instance.

CK: Another art form for you is clearly book making. You have such a concrete and strong sense of sequence. How did you feel when you made your first monograph? You’ve said in talks previously that you wanted one image per page, and for each image to speak for itself, and then realized that would never work. Can you talk a little bit about how that informs your process of making books, and how that has resonated with you throughout your career?

LC: Well, I tend to be rather stubborn. I had got into that project [Solos: Photographs by Linda Connor, 1979] thinking blank left, one picture, that’s got to do it. And boy, was I wrong. I had to admit it to myself [that it wouldn’t work] and start cobbling them together. The sequence was most visual, but also emotional. They still can have some unique content, but they’ve got to have at least a couple of elements that allow them to flow together. And that tends to be a formal, maybe a structural element or luminosity that carries through. There are elements of content, form, mode, and metaphor that you want to get a combination of those things working. And most of it is done with intuition.

Visually working with actual small prints that can be easily shuffled and moved around, and sometimes [you can] put into taped accordion sequences so that you can actually turn pages and get a sense of how your sequence is building. And when I’m working with students with issues of editing, I insist that they make card sized prints that they can move around until the images tell them the sequence that they need to be.

CK: Speaking about your new book, “Constellations”, has just been released. Can you talk about the construction of this book compared to your others? What was your draw to create a book that encompassed 50-60 years of work?

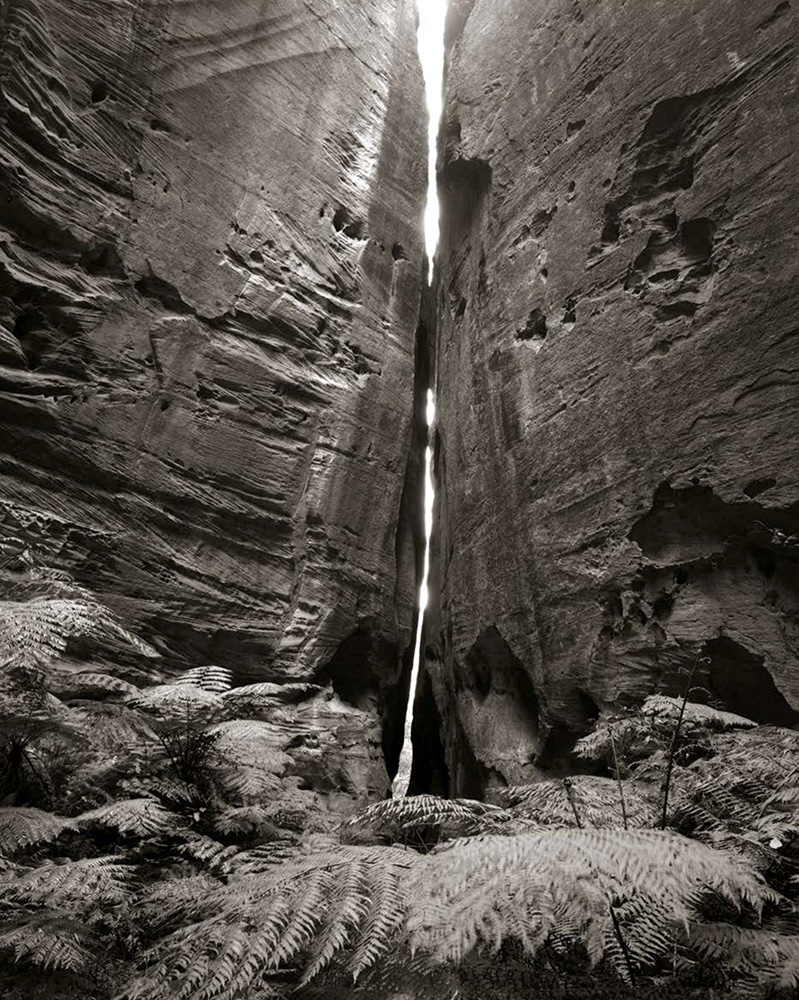

LC: We [Linda and her publisher Datz Press], wanted the Lick Observatory images to be the structure of it [alongside my images]. Sometimes there are obvious references to the sun or moon, or astronomical events. For instance, you have an eclipse with a sun peeking through, or you have this wall that had this crack with this bright light. And one thing I love about it is that there are no words except for a definition from an old dictionary. So you can pick it up anyway, and have a connection or surprise like that. It covers a lot of ground in terms of time periods and subject matter and natural energy. There’s maybe another level of metaphor that comes about in the sequencing process where the formal elements of a photograph will align with another image and in combination they create or reinforce both visually and metaphorically. For example, the final sequence I wanted to bring the closure back to the earth and into a human realm. So there are photographs of the island of Hawai’i growing with it’s molten lava, and landscapes and rock art that bring us home out of the night sky.

I’m really delighted with it. And Sang Yon Joo and Datz Press are such good artists and craftspeople. My sense of design is not as adventuresome and well developed as theirs. But then again, it’s my work and I’m stubborn. *laughs*

It took a long time to come to the final selection, and that was not helped by the travel restrictions of the pandemic and having to do all our editing and picture selection remotely. Until I had the book in hand, it remained somewhat foreign to me.

CK: Tell me about your time at the Lick Observatory?

LC: When I was still in Chicago, Imogen Cunningham had come out as a visiting artist for a week. I lived near campus and had a car, so I was the one who always volunteered to drive the artists around. I told her I was graduating, and I was thinking of either coming to San Francisco or maybe Seattle. I asked her if there anybody I should contact, and she said yes. She introduced me to Jerry Burchard. When [I went to meet him], I showed him some portfolio stuff and collage things I was doing with glass plate negatives. He mentioned that he had printed at the Lick Observatory at one point as a summer job. I registered that, and then I wasn’t finding a job, and months were going by. So I called Jerry back again to see if I could get a Lick Observatory contact. And he said he didn’t know about the Lick anymore, but we have a beginning classes opening up at SFAI. And that’s how I got my foot in the door there.

CK: Oh wow!

LC: But Jerry gave me a print [from the Lick] that they were discarding. He also mentioned a series of large astronomical glass plates of the Milky Way. I never forgot that bit of information. The idea of the Lick Observatory stayed in my imagination for many years. I finally located a contact there and was invited for a visit, at which time I met Tony Misch. He was in charge of the plate vault, which contained glass plate negatives of star fields, eclipses, comets, and other astronomical phenomena. I was in heaven.

During that period of using 8×10, I had been using printing out paper, and my print-exposures were done in sunlight. Since the great majority of the glass plates were 8×10, I travelled with my printing out paper and print frames and was able to do exposures directly outside the door of the archives. When the exposures were complete, I could take them out of the light, put them in a box, and bring them home for toning and fixing. And over about four or five years, I amassed quite a few beautiful prints with their permission, and could publish them with my work. There’s some question about ‘am I appropriating’ and all that kind of stuff, but I think there is a correspondence with [my other work] and sort of a romantic notion that we have our time span and cultures here on Earth, but there’s also this bigger space that we tend to forget.

CK: You seemed very fortunate to have made the connection you have at the Lick, but also throughout your career. What do you tell your students or younger photographers about reaching out to people in this industry where everybody is chronically busy and don’t have enough time?

LC: Nobody believes this anymore but I’m (or was) actually shy, but it’s useless to be shy. So I tell them that, you know, don’t be reckless but put yourself out a little further. You know, be enthusiastic about what you love, because that’s quite contagious!

CK: What advice would you give women photographers for how to maintain a long-term creative practice?

LC: I think you don’t have a choice. I think you could do your art without an audience, if you have to. I mean, I think it’s important that you have some peers, some feedback. But if you’re a musician, you’re a musician. You’re just going to be that. Maybe you have to take on some other work as well or live more simply. Trust yourself and then try to find a good community that loves you and trusts you and will help and support you.

Cassandra Klos (b. 1991) is a fine art photographer and curator based in New England. Exploring the unexplainable through visual investigation, she uses storytelling and photography as a method to breathe life into situations where visible manifestations may not be available. Her interest in science fiction, belief, and historical archives guide her articulation of how images can discern the multifaceted ways in which we unpack traumas, believe in what we cannot see, and examine hope in our culture.

She has exhibited across the United States, including solo exhibitions at the Griffin Museum for Photography and the Boston Public Library, as well as internationally in festivals such as the Bienne Festival of Photography and the Lagos Photo Festival. She is a Critical Mass finalist, the recipient of the Yousuf Karsh Prize in Photography as well as a Traveling Fellowship from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and a Kenan Institute of Ethics Fellowship from Duke University. Her work has been seen in TIME, National Geographic, Wired, The Atlantic, and Smithsonian Magazine, among others. She is a 2020 MFA graduate of Duke University’s Experimental and Documentary Arts program.

Follow Cassandra on Instagram: @cassandraklos_

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Marcia Molnar: The Silence of WinterDecember 24th, 2025

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

![Connor, Linda_Constellations [detail], Datz Press 2021_08](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Connor-Linda_Constellations-detail-Datz-Press-2021_08.jpg)

![Connor, Linda_Constellations [detail, title page], Datz Press 2021_07](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Connor-Linda_Constellations-detail-title-page-Datz-Press-2021_07.jpg)

![Connor, Linda_Constellations [detail, spread], Datz Press 2021_09](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Connor-Linda_Constellations-detail-spread-Datz-Press-2021_09.jpg)

![Connor, Linda_Constellations [detail, back cover], Datz Press 2021_12](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Connor-Linda_Constellations-detail-back-cover-Datz-Press-2021_12.jpg)