Photographers on Photographers: Joel Jimenez Jara in Conversation with Alec Soth

Over the next two weeks, we are sharing some of our favorite Photographers on Photographers posts. Enjoy! – Aline Smithson

I learned about Alec Soth’s work right when I was starting my sophomore year in college when I was studying photography. A professor showed me his work for the first time through a photobook (A small version of Sleeping by the Mississippi contained inside the Gathered Leaves compilation).

I was immediately struck by it. A whole world opened up to me regarding the possibilities of photography and the conceptual threads that hold a project together.

Alec’s work is both about distance and connection, his images have followed me in my practice and have been an inspiration while I find my voice in this medium. Looking at his photographs, I felt an immediate bond with the atmospheric qualities of the spaces and subjects he portrayed.

This dichotomy of solitude/longingness is something that I relate to on a personal level, and in a way, those themes follow my work as well.

This conversation for me is about engaging with someone that shares common interests and is passionate about the same inner struggles that I carry with me. This is about longing for a connection while we navigate the current sea of separation that divides us.

Alec Soth (b. 1969) is a photographer born and based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He has published over twenty-five books including Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), NIAGARA (2006), Broken Manual (2010), Songbook (2015) and I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating (2019). Soth has had over fifty solo exhibitions including survey shows organized by Jeu de Paume in Paris (2008), the Walker Art Center in Minnesota (2010) and Media Space in London (2015). Soth has been the recipient of numerous fellowships and awards, including the Guggenheim Fellowship (2013). In 2008, Soth created Little Brown Mushroom, a multi-media enterprise focused on visual storytelling. Soth is represented by Sean Kelly in New York, Weinstein Hammons Gallery in Minneapolis, Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, Loock Galerie in Berlin, and is a member of Magnum Photos.

Follow on Instagram: @littlebrownmushroom/

Joel Jimenez: How has your relationship with photography changed your perception of ideas related to longing/separation over the development of your practice?

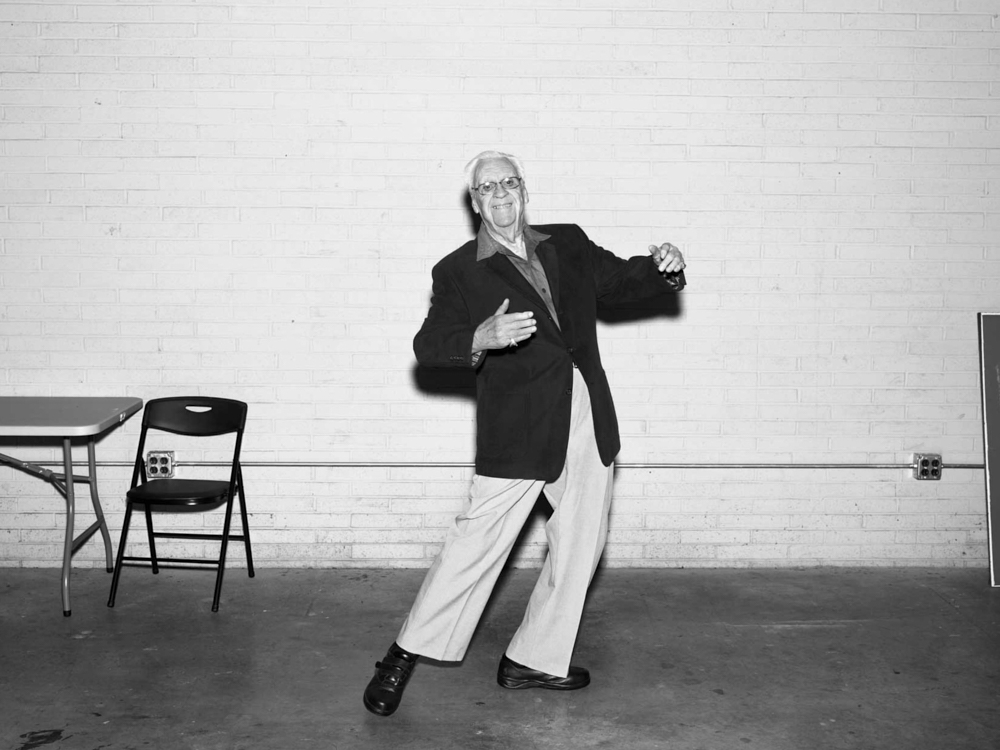

Alec Soth: Yes and no. We might as well start off this interview from the therapy couch. I actually talk about my photography a lot in therapy. It’s impossible for me to untangle my creative work from my psychology. If I’m honest, I think that photography is in itself a form of therapy for me. When I first found photography, the camera gave me an excuse to wander around alone and indulge my emo tendencies. Later it functioned as a tool to engage with other people. What’s interesting to see now is how integral other people are now in my creative process. I’m not just talking about the subjects I photograph, but my collaborators and assistants. The 20-year-old me would never have guessed that I work the way I do now. But underneath all of that process stuff, that emo boy is still there. When I’m alone planning work, or editing, that part of me comes back to the surface. The process and audience for my work might have changed, but there’s a core part of creative self that remains the same.

AS: But let me turn the tables and I’ll play the therapist. Tell me about the psychological need that brought you to photography, Joel.

JJ: I relate a lot to the idea of photography being therapeutical. For me, it works in the sense that by thinking about my own work I uncover a lot of stuff that I wouldn’t have thought of about my past.

Throughout my childhood and teenage years, I spent a lot of time in solitude in my home. That was because my parents were somehow overprotective and after a while, I started to be comfortable with the idea of being alone. (Although I had a lot of emo moments in-between).

When you’re alone that much I think it’s natural to become an overthinker. I dealt with that a long time but it wasn’t until I found photography that I could channel that energy into something creative.

My natural process of working usually balances out between dipping outside my comfort zone and having a safe space to work in. Each project has been a learning process to step even more outside that safe space, especially when producing the work. In the editing, just like you, I go back to my inner way of being just with myself.

In that sense, photography for me is also about connection. Not only a connection to myself but new spaces. Because of my childhood, I am very receptive to the feelings of a place (more so than people), so it came naturally to work around the idea of the environment as a central ground for inner exploration.

JJ: How has your relationship with solitude and connection changed throughout your career?

AS: As I said, I was attracted to photography because it was an excuse to wander around alone. But in and of itself, this is a creative dead end for me. I’ve learned that I’m fundamentally making art in order to connect with others. Sometimes this connection can happen while photographing, but it can also happen in a book, exhibition, lecture, interview, etc. Lately I’ve even been doing live performances. I never would have expected my career would take this turn. I mean, public speaking was my single biggest fear. I had to face this in order make connections with my art.

AS: I’m fascinated by the fact that some artists are content to make work entirely for themselves and have no desire to share it. How important is the sharing of your work?

JJ: I think I’m learning the lessons that you mention as I keep developing my work. As I said, I learned to be seclusive and to not have a lot of interaction with others and my work reflects that in a way. But throughout the years I’ve noticed how the distribution of my work and the immediate connections that follow it have been very nurturing and fruitful.

It is through photography that I’ve found best friends to talk to, and new people to connect with, so I do believe that my work is a channel for me to interact with the world.

Going back to the emo tendencies that you mention, being an overthinker and a loner also drags a lot of insecurities about being misunderstood. Photography has helped me see that the barrier between myself and others may not be that big especially when I allow myself to connect from just the feelings of things and not necessarily from an intellectual level.

JJ: As we continue to live through a life-changing experience in this pandemic, I wonder if personally there has been a defining moment(s) that changed the way that you approach your work? Could you share an experience that did that for you? (besides the pandemic)

AS: One of the key moments of my creative development happened in the months before my first real trip for Sleeping By The Mississippi. I had a full-time job at an art museum. After being awarded a grant, I managed to negotiate a three-month break from my job. It was a big deal. But just as the time came for my trip, my mother-in-law entered hospice. I was extremely close to her and there was no way I could leave. So I stayed with her and my wife as she died for the first six weeks of my time off. When I finally left, everything felt different. Having just watched someone die, I felt totally fearless. I never would have made the work I did along the Mississippi had I not gone through this experience.

AS: You mentioned the pandemic. I’m curious, how this affected your creativity?

JJ: It’s weird what loss does to you sometimes. Right before the start of the pandemic, I was dealing with a break-up that ended up pretty bad and had family involved and that sort of stuff. In-between that event, my grandmother died, and even though I wasn’t close to her, my father was devastated.

I had to leave my feelings behind to take care of my dad while he was going through his process, but that kind of made me contain all the sad feelings about my situation. It all exploded right when the pandemic came and I was alone living in another country with all the uncertainty that we all had at the beginning.

I was able to go back home after a while but in the first half of 2020, I was dealing with a lot of stuff emotionally. I couldn’t think about work and I wasn’t really enjoying anything that I was achieving. When that slow recovery kicked in and I was better, it was like a jump start. I started doing 10 times the things that I was doing before, learning a lot of new things from other mediums while also reconnecting with photography.

While I haven’t produced new work (in the form of a project) I carry those experiences with me with appreciation. I honestly believe that the next thing I work on is going to have that weight of emotions and ideas within the images. I’m grateful, and I think there’s no better feeling than that.

JJ: As you continue to develop your practice after a relatively long time, what are the main differences that you see between the earlier work and the work that you’re motivated to do now? What do you think the earlier you had that you don’t? What do you wish the earlier you knew that you now know?

AS: That’s such an enormous question. One of the biggest differences, I suppose, is the effect of the audience. In the beginning, of course, I had no audience whatsoever. There was a kind of freedom in this, but I don’t want to overromanticize it. Instead of having an audience, however small, I had an imaginary audience in my mind that had no basis in reality. This was strangely paralyzing. It was actually much better to have the small audiences I had when I first had shows in unglamourous venues in Minnesota. I imagine this is the way bands feel when they first start getting gigs in little clubs. There’s a feeling of freedom. As the audience gets larger, things get more complicated. And money comes into the picture, which screws with everything.

But none of this actually answers your questions. So let’s see, the main difference between my earlier work and the work I do now? My earlier work was mainly future driven: imagining the life before me. Now my work is just as likely to look backward. Once you have some history, this becomes an integral part of the work.

There’s an energy to naivete. I can see this in Sleeping by the Mississippi. There are a bunch of things I wouldn’t do now, but I also understand that this is partly what gives that work its energy. There’s no way for me to manufacture naivete now. But I can experiment and do things that make me uncomfortable. That is important.

I don’t have regrets. Sure, it would’ve been nice if I’d been less neurotic when I was younger, but if that were the case, I probably wouldn’t have been making art in the first place.

JJ: Could you share one memory of producing a photograph (the experience of making a photograph) that you’ve held for a long time? What is it about that memory that you hold close to?

AS: There’s a picture in Songbook that I think about a lot. It’s of a couple in a bedroom with their faces obscured. The experience taking it was notable. I was working with my collaborator, the writer Brad Zellar, in Denver. We were waiting outside of a church to talk to someone when the couple walked by. I decided to go with them while Brad went to the church. They ended up inviting me to their apartment and we took the pictures.

A couple of months after sending them a print of the pictures, I got an email from the young woman in the photograph. She told me that the man had fallen down a flight of stairs and died. I printed more pictures for them for the funeral.

Photography is so wrapped up with death. It feels profound when actual death interacts with my experience of the photo.

JJ: Could you tell me about a non-photographic work that has helped you expand the way you think about photography? (if you could give a concrete example)

AS: I find it extremely helpful to read books about creativity from non-photographic artists. I just got back from a road trip in which I listened to Jeff Tweedy read his book, “How To Write One Song.” I have no musical talent and zero interest in doing any songwriting myself, but everything he wrote about was extremely helpful. Then when I listened to his music, it became even better. I’ve always loved Yankee Foxtrot Hotel, but listening to it after hearing Tweedy talk about his creative process made me excited to dig into my own work. That said, poetry is probably the medium I turn to first when looking for inspiration.

AS: What is your non-photographic go-to medium to stoke the creative fire?

JJ: For me it’s movies. I’m actually learning and developing in filmmaking parallel through working on my photo projects. It’s also funny because a lot of my photo motivations carry on to what I like to watch and produce in film.

Sometimes when I overthink about it, I feel that I’m dragging one medium into another and not really getting what “movies” should usually be. But other times, I believe it puts me into a position that I can do work that I love and that has a distinct quality to it. Either way, I’m learning about it as I go.

Regarding movies or directors that I find inspiring, Tarkovsky is something that I always go back to. For me, his book in which he talks about filmmaking and his work pushes me to be better and honest about my feelings when working or editing photography.

I can say I have an almost spiritual experience when watching some movies, at least on the sensorial level. Most recently, I’m trying to watch a lot of Taiwanese and Japanese films. They have an aura that I can connect with, and it makes me want to try new things as well regarding my own work.

JJ: I’ve seen that you’ve had periods where you took a step back from photography to develop in other fields. What draws you back to photography?

AS: I’m not a multilinguist, but I suppose photography is sort of like my creative first tongue. I never feel like I lose this language and it’s always comfortable to come back to.

JJ: What parts of your processes (producing photography) have changed throughout the years and what has stayed the same? What kind of strategies or exercises could you suggest to an artist that feels stagnant with his work?

AS: Since photography is a medium bound up in technology, it inevitably changes vary quickly. For my entire career I’ve had to deal with finding new solutions for printing, scanning, archiving etc. I find this all sort of annoying, but it’s the price I pay for being a photographer rather than a painter.

While this technology has had a big impact on my day-to-day job, it hasn’t had as much of an effect on my creative process. If anything, technology has helped my creativity. The research I’m able to do on the Internet paired with digital mapping tools has actually allowed me to dive deeper into the world.

I have a number of ways of defeating stagnation, but it all comes down to play. In the Jeff Tweedy book I mentioned, he talks about watching his kids on the floor coloring. The kind of informal, non-judgmental absorption kids have while playing vanquishes cynicism and stagnation. We can’t expect to achieve this state all of the time as adults. But it’s important to find time for low stakes play. It can take any number of forms. Years ago I would build little cairns out of rubbish as I traveled and photograph them with my iPhone. I had no intention of doing anything with these images. They existed solely as an excuse for me to play like a child. More recently I created one-of-a-kind zines using pictures from web searches. The goal was nothing more than my own immersion in the process.

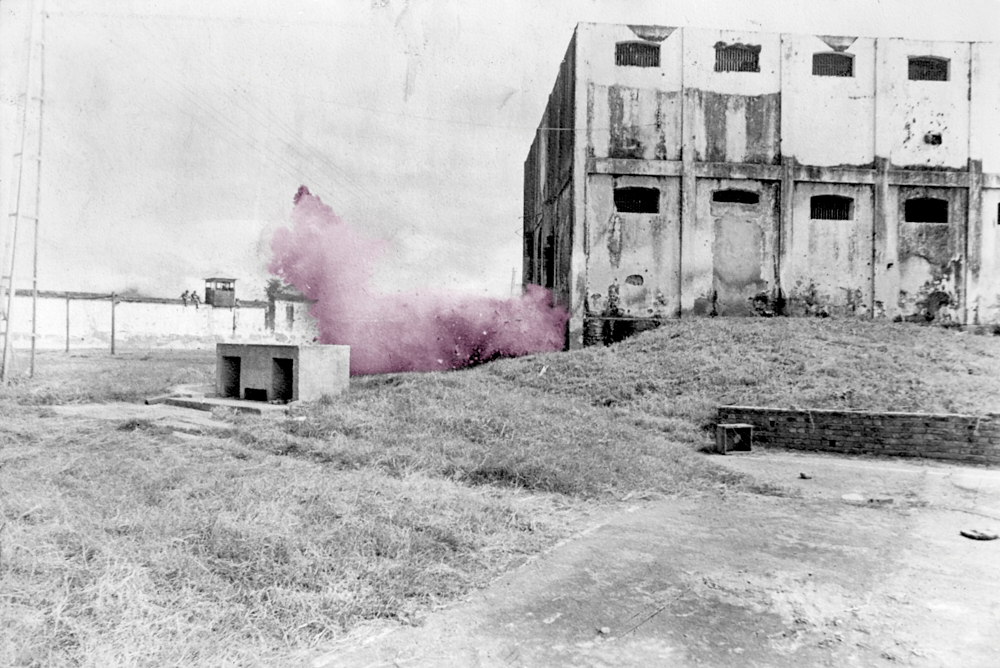

© Alec Soth, Cammy’s View. Salt Lake City from the project I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, 2019

JJ: What do you think are the key factors to sustain a practice in a field such as photography for a long time? (in your experience)

AS: For me the key has been to not have my eggs all in one basket. Along with my own personal projects I do editorial work, teaching, and experimental collaborative projects like my recent work with the musician Dave King. All of these activities keep my on my toes creatively. It also helps economically. When the art world collapsed in 2008, I was able to sustain myself with editorial and teaching gigs. But by not being a full-time commercial photographer or shooter, I haven’t gotten worn down from that kind of work.

AS: Do you do any teaching or editorial work? How do you balance the day-to-day need to make a living with your creative ambition?

JJ: I’m fortunate enough to be studying film at a university with a full scholarship that helps me get through financially. It also gives me a safe space to try things with film without feeling so much of a failure.

But besides that, I try to collaborate with other people in their work or produce new things together. I’m grateful to have a few friends that allow me into their creative process and let me help in editing or general feedback. That has led me to teach informally occasionally, but I’m planning to keep doing it more frequently since I really like it.

This year I’ve also been part of different platforms that connect photographers to interchange photographs, like an image conversation. That has been great, and I’m about to start another one that I’m excited about. These spaces allow me to experiment and to feel the need of being out there, but without the added pressure of developing a big project.

I’m also into curating and exhibition design, I’ve been developing a project about photographers from my country. I believe that providing a channel or a platform for other artists from my region is something that I would like to do in the near future.

JJ: What do you think are the biggest challenges that young artists/photographers have at the moment?

AS: Whether or not you are an artist, social media is screwing with everyone’s head. Nearly everyone I know is anxious. This anxiety strikes me as being incredibly unhelpful to the creative process. But at the same time, it’s clear that artists usually need to engage with social media in order to build a career. Finding this balance is nearly impossible for me. I can only imagine how much harder it is for a young artist.

AS: What is your relationship with social media? Do you feel a significant difference in your relationship to it that people who are younger than you?

JJ: I struggle a lot with the first question because I have a love-hate relationship with social media. On the one hand, it is because of social media that I learned about Lenscratch, so we’re having this conversation because of it.

On the other hand, it adds an immeasurable amount of noise and pressure to my daily life. I’ve been wanting to disconnect and have a break from it for a few months. But I haven’t been able to do it because the idea that I might miss an opportunity to learn about an open call or a platform that might help me grow always makes me go back.

As you said, as an emerging artist that is slowly trying to build an audience and exhibit his work, I have to be attentive to the strategies that would best allow me to have some exposure, and hopefully, that allows me to keep producing new work through funding or other options.

But social media makes me feel like that attention needs to be on 24/7 and that’s exhausting. When I have a break, it’s always on the back of my mind, so I’ve been trying to minimize my consumption and to be selective on what I see on those platforms.

Once I start producing my next work I will probably let it go for at least a month or two, to have a little space in my head to process my thoughts.

Regarding the second question, I think that the main difference between myself and the younger generations is the fact that I do not use short-form video content (like tik-tok or ig stories) to express my thoughts. It seems that younger people rely more on that nowadays.

JJ: What are the biggest challenges that you face in producing new work at the moment?

AS: I would say those very forces I just described are the biggest challenge. I do my best work when I get all of the nagging voices out of my own head. Social media has introduced thousands of new nagging voices.

AS: What is your biggest challenge?

JJ: Overcoming the impostor syndrome.

Learning how to not to have tunnel vision when I’m very passionate about my ideas and be more open to new paths.

Knowing when to start and when to stop.

JJ: As visual arts keep crossing one another, do you think that new generations should approach their thought process regarding photography differently? Do you think that younger generations should explore other fields as a fundamental part of their practices?

AS: When it comes to other artists, I try to avoid the word ‘should.’ What makes art interesting is the variety. Take music as an analogy. I think it’s great that there are musicians that use sampling and all sorts of digital sound modification tools, but I’m also glad there are traditional musicians playing banjos or whatever. There’s plenty of room for both. The same is true in photography.

JJ: As you’ve worked extensively with photobooks, how do you think the visual language of that medium has changed from other periods? What would you like to see regarding newer generations and their approach to photobooks?

AS: Though I’m not the photographic equivalent of a banjo player, I would say that my taste in photographic books leans toward the traditional. So while I’m happy for there to be all sorts of experimentation, it’s generally not what gives me the most satisfaction. It’s the work itself – the pictures and sequencing – that means the most to me.

AS: For a long time, I believed that younger generations would create large-scale projects online and that this might replace the photobook. When I gave talks at universities, I’d often say “One of you is going to make the equivalent of The Americans online.” I no longer believe this. People are of course making photographs for purely online distribution, but it’s done in a fragmentary way that bears no resemblance to photographic books.

What do you see as the future of photographic distribution?

JJ: I also tend to like projects that are presented in more classical distribution methods such as photobooks. The pandemic brought forth a lot of thinking about virtual exhibitions and digital storytelling and I think that’s very interesting.

I personally don’t like virtual exhibitions that imitate a real space because for me there’s no way to replicate the experience of actually being in a space with the work. In the same train of thought, I find that photobooks provide a totally different experience than digital viewing.

There’s something about the tactile properties and the physical experience that I think it’s going to translate to new approaches of distribution with technological advances.

Maybe we will have photobooks or exhibitions in the future that are more immersive that go beyond the bidimensional frame of viewing photography. Maybe 3-D printing is going to be used to exhibit a photographic image but with volume, or a display technology is going to allow us to involve other senses directly in our experience with photography.

For now, I would just like to focus on working on my own inner experience with photography and to understand myself better with it, sharing the process along the way.

Joel Jimenez (b. 1993) is a visual artist, cinematographer, and independent curator who lives and works between Costa Rica and Spain.

His research-driven work explores themes associated with environmental psychology, place-identity, and the role of memory in our conception of history, perception of reality, and understanding of time.

His projects are interested in the in-between states, the emotional climate that emerges from stagnant conditions, and the atmospheric experience of silence, solitude, and nostalgia.

Joel’s work is shown internationally in group and solo exhibitions including PhotoEspaña, Singapore International Photo Festival, and Photo Israel. He was selected as a LensCulture Emerging Talent, Fresh Eyes talent, nominated twice for Prix Levallois, and a participant in portfolio reviews like Emergentes in Encontros da Imagem. His projects have been featured extensively in printed and online publications such as the British Journal of Photography, GUP Magazine, LensCulture, PHmuseum, Der Greif, Revista Balam, among others.

Follow on Instagram:@joelr.jj

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography & Anthropology: Raquel Bravo Iglesias, “Mato Grosso”May 1st, 2024

-

Earth Week: Ian van Coller: Naturalists of the Long NowApril 22nd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Shari Yantra Marcacci: All My Heart is in EclipseApril 14th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024