Julie Hamel: The Known Unknown

Unprecedented levels of interconnection have brought upon us the genesis of new solitudes. Life booms with the startling roar of a high-speed clout chase that waits for no one. Granting ourselves the right to stop has become, among other things, a dreaded nuisance, an economic impossibility, and one of the most restorative acts of self-care and personal resistance. Julie Hamel‘s large-format pinhole photographs remind us that being present requires more than just courage. It requires a sacrifice: to venture into the woods of uncertainty and let go of what was and what could be.

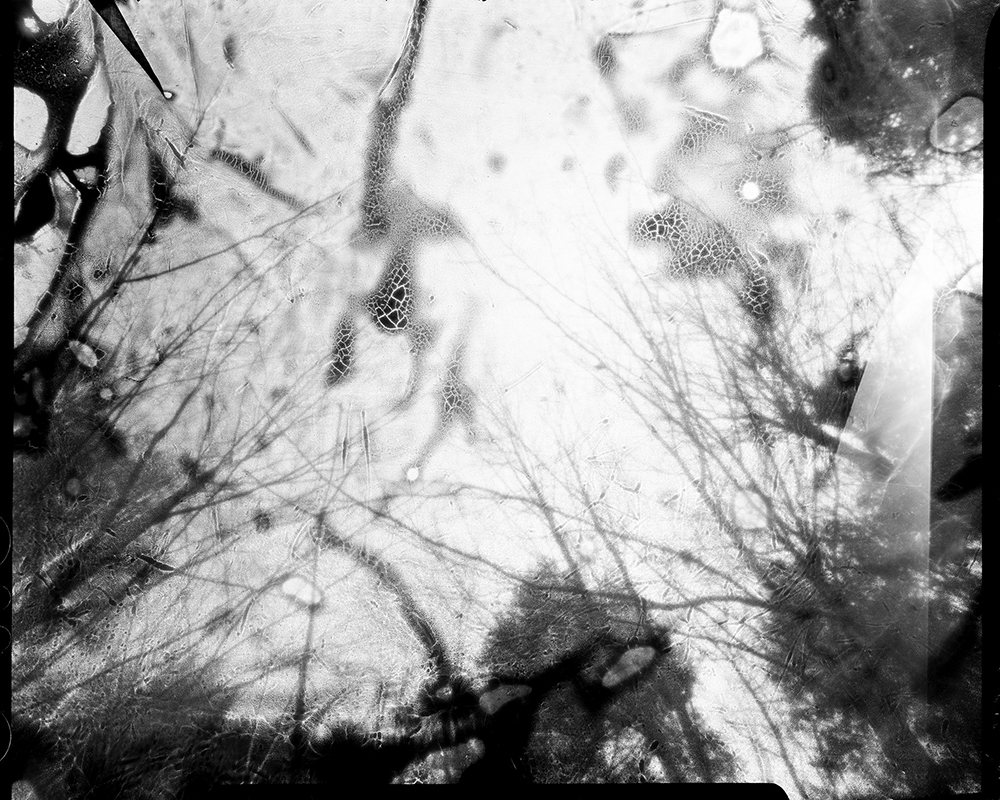

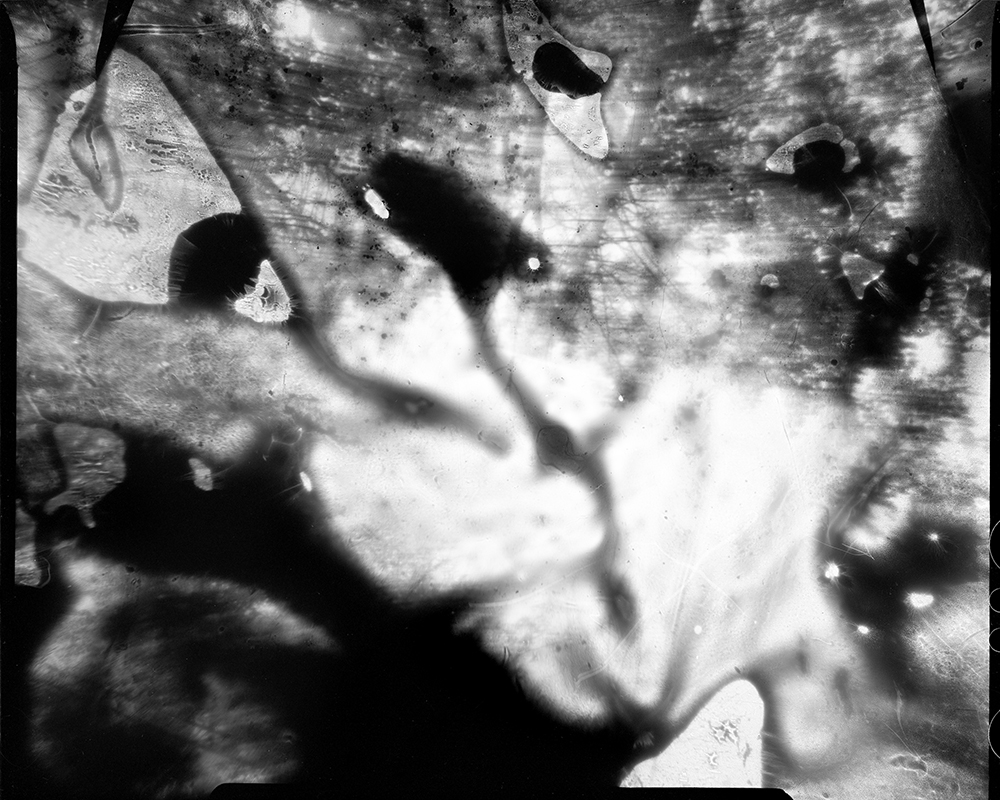

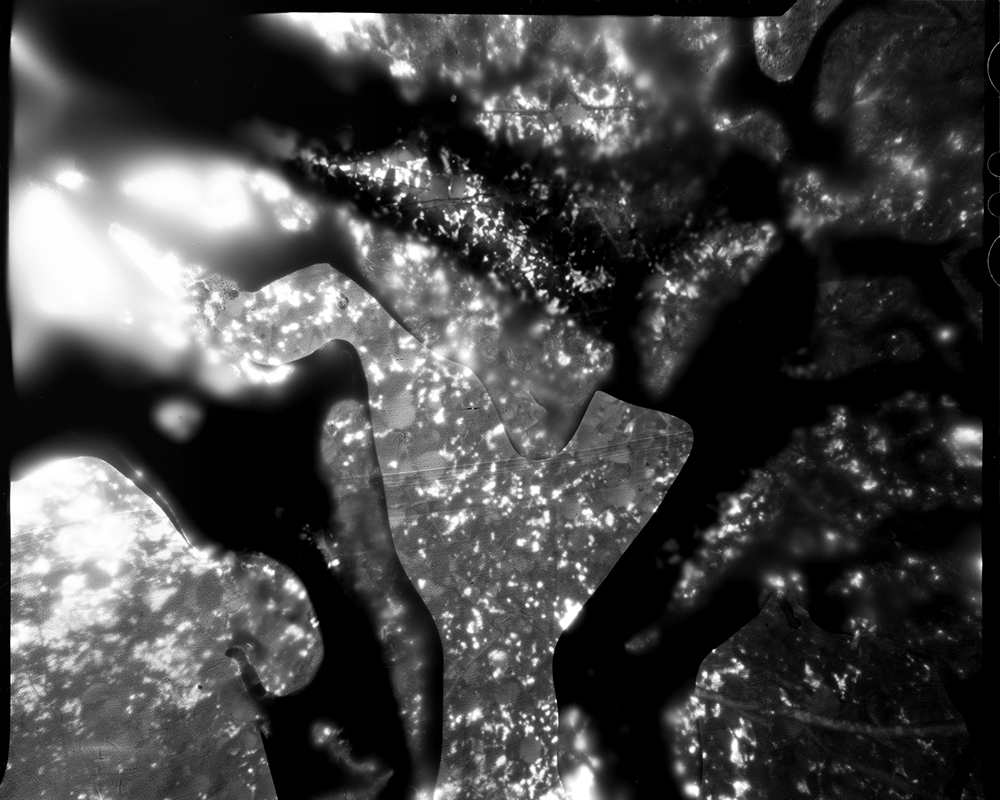

Each 4×5 film in The Known Unknown (2022) was covered in camera with a thin veil of the artist’s blood. The resulting contact prints shimmer like liquid visions that seek to mend the rupture between image and photographer, nature and self. Hamel’s explorations of the New England woods, however, are not merely a melancholy record of our disrupted, if not vanishing, reverence for nature. They are also a reflection of our increasingly precarious position in a cataclysmic world where loss and separation render us interpersonally adrift. “With no real direction or goal other than keeping one’s head up,” the series teems with a multiplicity of affirmations that prove ever more fragile in the contemporary landscape: “I am here, I belong, I matter.” Tenderly rocking the viewer in and out of dreams until full awareness, each photograph pierces the cornea with the disorienting glow of hypnagogic hallucinations. The enigmatic vistas ring strangely familiar: branches, veins, and flowers endlessly unfolding, free and turbulent like the rising sea and our longing for connection.

In this interview for Lenscratch, New Hampshire-based photographer Julie Hamel speaks to Vicente Cayuela about her inspiration to create work addressing care, the emotional toll of separation, and the grounding nature of her process.

The Known Unknown

Each image in The Known Unknown is a consideration of self. In this exploration, only fresh air and footsteps are exchanged with the land, with no real direction or goal other than keeping one’s head up. A thin veil obscur es the landscape and encroaches onto the sky during each long exposure of the 4×5 film, reminding us that we are never truly still even when resting. The simple act of wandering alone in the woods creates a practice of slowing down and claiming a space: I am here, I belong, I matter. Capturing these moments in time allows us to identify how we are connected to the environment, to others in our lives, and most importantly to ourselves. The repetitive and disorienting nature of the work allows the viewer to consider the cycles in our daily lives. Reflecting on the internal conversation, and how this translates into the actions we take to care for ourselves, is an attempt to map the overwhelming unknown.

Julie Hamel is a multidisciplinary maker working with photographic media that speaks of loss and memory. Frequently using what’s found in nature to highlight the distance in human interactions, marking the importance of the connections, and the emotional effects of separation. Julie received her BFA in photography, and a fellowship from the University of New Hampshire in 2010. She received her MFA in Visual Arts from Lesley University College of Art + Design, Cambridge, MA in 2021. Julie has won numerous awards throughout the states, and has shown across the US and overseas including Italy, Budapest, Greece, and England.

Follow Julie Hamel on Instagram: @juliehamel_inprogress

Vicente Cayuela: Julie, thank you so much for joining me. We are both calling in from very rural areas, so I hope our connection is stable enough. [laughs] I am very excited to learn all about the process behind these disorienting and intriguing photographs of nature.

Julie Hamel: Thanks for having me, Vicente. My process(es) have always been an essential part of my practice, so that is a great place to start. The Known Unknown was captured with the use of a large format pinhole camera which allows for a considerable amount of space inside the camera, as opposed to a traditional film back. This is something I’ve been experimenting with for a few years now. I’ve been using small bags of liquid that I slide on top of the large format film. Through this process, I am capturing an image and creating a contact print simultaneously. Once I find a place that feels or looks right, I then place the camera on the ground, a tree, or wherever the spot may be, and I shoot up toward the sky. That shift is when gravity whisks the current moment away. Depending on how long I have been walking or where I’m traveling, I may need to crawl over obstructions, which also changes the amount of agitation within the camera and ultimately the final photograph.

VC: Your mappings of nature interest me because they encompass psychological states, bodily actions, and reactions to land all at once. Why do you choose to deal with these subjects?

JH: My work has always been connected to organics and the outdoors, specifically the changing of seasons. The cyclical nature references relationships for me, how objects come together, how people separate, how things grow or decay, invasive species, and what happens when they are introduced into a landscape. All of these actions really respond to how we as humans communicate with each other. The majority of my work speaks to intimate relationships and how they form, grow, and for me—the most interesting—how they end. [sighs] So much of nature is out of our control.

VC: What does it take to find the right shooting location? Is it an emotional response or a sort of spatial, more bodily awareness?

JH: Both, all at once. That was something really important about this specific series and one of the reasons I fully committed to it. Most of my work involves remnants of nature and collecting materials that always have me looking down. I’m scanning the ground for objects that have dropped or died, things that have scattered, or been left behind. For this series, I really wanted to look up. That commitment shaped how I moved through the world in 2022. It forced me, in a way, to create an almost subconscious physical positivity. Through this act, I would then stumble across an interesting tree or a beautiful opening in the forest, a moment that felt right.

VC: I am intrigued by what prompted you to look up and the consequences of shifting your perspective, both in psychologically and in your art practice.

JH: I believe it was the realization that at some point if you want something, you have to force yourself into that change. When I am searching for remnants, I always look down, but what does that mean for the body and the mind? The act of physically putting your head down, to be almost hunched over, how does that change your body and subconsciously change your mindset? At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter if my stature occurred for an artfully beneficial and positive reason, which was to collect materials for my art. But I think that the pandemic came to a point where I was so isolated and tired that it felt hopeless. [pauses] You have to make these physical changes within yourself if you want anything to happen mentally or emotionally.

While walking the woods, and consistently looking up, it reframed the land. I thought of the connotations of how we navigate life and different geographical locations without a map. There are multiple ways of doing this: watching the directional flow of a river, finding moss on trees, or even the course of vine growth. But for as long as humans have been around, we have looked to the sky. For direction, time of day, and seasons. The sun and stars have been our main guiding forces. Through the act of saying, “I am going to look up wherever I go for a year;” your posture changes, and what you notice shifts in the world. It was important to make that a rule for myself in a way. This series is about the claiming of space, being present, and feeling that one should matter in their present location.

VC: How did this new way of seeing present itself aesthetically and emotionally in your photographs compared to your previous works? Did it bring any challenges?

JH: When you work with a pinhole camera, everything gets flipped upside down and left to right. It is not common practice to put liquid inside of a camera, but if you do, you are going to be fighting gravity. In every photo you capture, you will always have the same orientation of the liquid. In this case, the images would always have black at the top and that’s not how this series was envisioned. It made sense to remove the gravitational aspect and in connection to that, the known spatial awareness of where you or the image stands. By placing the camera on the ground and focusing on the sky, the camera itself is now in a state of rest, lying on its back, comforted by branches or blankets. Doing this allows me to find my own orientation. For each image, there is no preconceived top or bottom—meaning the viewer is unable to identify orientation by a person, building, or sense of weight. The images fall into a realm or spectrum of pure feeling. Once I take the image, develop it, and scan it, I spend time continuously rotating and sitting with it. I enjoy the moment when it looks back and I know, “this is the right orientation.” It feels like a reflection of one’s emotions. [pauses] How you feel about yourself at a given time, you get to choose.

VC: To a certain extent, you ended up losing control of the image during this new process. Do you attempt to regain a sense of agency?

JH: As with any new process, the more you do it, the more you realize what happens. Some of the bags I have kept the entire year, causing the contents to become dry and cracked. If I bring them into the woods, they are more predictable and stable. There are other times when I’ll shake a bag before or I’ll let the camera rest overnight with the liquid in it, and then I’ll carry it that way. However, there’s not a lot of control when you’re working with external forces, and I think that’s also a reflection of us as people and how we respond to the world around us.

VC: Bodily fluids are often stigmatized in society and art, and the use of blood is obscured in this series. Did its use have mainly a personal meaning or did you want to communicate something specific to a wider audience?

JH: That is a great question. I believe a lot of people may have preconceived notions when it comes to the use of blood in art. I find that a lot of my work is a conversation with myself internally and the audience views the final transcript. I felt a great amount of stress when I started this series. It became emotional and a lot of pressure built up inside… until it had nowhere else to go, but outside. I had been working with shooting through organics for a long time with my thesis work and it became a what-if situation.

Without thinking, I brought myself, in person, and in hand, into the landscape. It was a very organic and subconscious process. But the more I was walking with the camera, the more I thought about carrying myself, and what it meant to carry oneself in the landscape, in a person, through relationships. How do we carry ourselves through our daily lives?

In the simplest terms, this allowed each image to look through me. When speaking about photography, you always hear people say, “the eye of the photographer,” but what about the body? What about the essence, or you know, what actually keeps us alive?

It became a personal act, protecting, caring, and a kind of reprise, as in the camera always being at rest during these long exposures, which was really interesting to me. As time went on, I started to consider, Where do the bags end and the “baggage” begin?

VC: I love that you talk about the difference between the eye and the body! This is such an important conversation right now—the idea of land and landscape and the non-neutrality of the landscape genre. That sort of dichotomous thinking sustains the idea that photographers and the places they photograph are two separate entities. In my eyes, putting blood in contact with the film becomes such a strong statement about reclaiming a sense of unity.

JH: Yes! I often think, “what is a camera to a photographer?” It’s something that stands and separates you from the object. Obviously, you can step to the side, but what you’re doing is separating. Within this series, I am inside the camera. There is no separation between myself and a contact print on this film. This indexical moment speaks to physically being there, existing and mattering at that moment in nature and time.

VC: At the peak of the pandemic when I was the most lost and isolated, your photographs helped remind myself that healing comes from changing our perspective. Do you mind if I ask where are you in your healing process and what role has photography played in it?

JH: Art can be a compelling force and often touches us in profound ways. To know someone was moved by a specific piece is truly special, so thank you for sharing. To answer your question, I do not believe that anyone is ever done healing. So like many, I am in the process of doing that. Without a doubt, each day will bring a new situation to heal from. It’s much like nature in a cyclical form where we ebb and flow from our surroundings. I’ve always created art but photography for me is a way that my subconscious can tell me what I may not be paying attention to. A lot of the work revolves around the separation of relationships. Through creating these works, I might not know why at the time, but if I sit with them long enough, it starts to make sense. I can understand why that specific part of the process was important. It’s like when you dream, you often feel caught off guard or confused. Sometimes when you sit long enough you can see how it relates. For me, art is essential to life. It’s needed.

VC: I’ve been fortunate to see the creation of this series since its infancy and now I have the pleasure of interviewing you right at its completion. How did you realize it was finished?

JH: I love that you asked this question after inquiring about healing, I feel they go hand and hand. When thinking about one’s emotions, or a series, what does it mean when you know something’s done? How do you know you’ve healed? How do you know this is the end and you can move on and concentrate on something else? In this case, it was reflective of the cycle of nature. I started the Known Unknown in January 2022, and it made sense to have a full year recorded in these images. It also made sense because of the blood, no one was harmed. Obviously, it was mine, it was menstrual. The act of having a period is a cycle, but it is also about giving life, while at the same time stating that no life was created. The body versus nature is really prevalent in that conversation. It was beneficial to know that I wasn’t going to take a single shot for this series in 2023. This is what it is and that gave me permission to wind down. It was really important to the internal dialog once I presented it in that light. I was able to ask fewer questions and focus on filling in the answers—the gaps.

VC: What’s in store for you? Are you already working on a new project?

JH: I have multiple projects in mind for the future, but mostly I am still reflecting on The Known Unknown. Much like healing, I think there is a lot to unpack once the dust settles. I am still considering the separation of relationships and what that may look like in a very physical form.

This past year we have all gone through a lot of changes, or should I say movements. There is a life outside of creating that does not involve walking through the woods and shooting long exposures that fight gravity. Movement is connected to change and shifting directions, relationships, and perspectives. I find myself and my work to be balancing between a tangible realm and a photographic one. Looking to the future, I am hoping to contemplate this connection between the mind, body, and environment in a more kinetic way. I am interested in uncovering what this new consideration of physical movement will mean both through the process and the final work.

Vicente Cayuela is a multimedia artist working at the intersection of staged photography, sculpture, and installation. His handcrafted photo-based artworks create colorful scenes of graphic overload and tongue-in-cheek cultural commentary inspired by juvenile aesthetics and material culture. His work has been exhibited in New England most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, the St. Botolph Club Foundation, the Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally. In 2022, he was awarded the Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the St. Botolph Club Foundation, in Boston, MA, and was one of the seven winners of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize. Cayuela holds a BA in Studio Arts from Brandeis University, where he received the Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography and the Deborah Josepha Cohen ‘62 Memorial Award in Fine Arts.

Follow Vicente on Instagram: @vicente.cayuela.art

Website: www.vicentecayuela.com

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025

-

Erin Shirreff: Permanent DraftsAugust 24th, 2025