Julieta Christofilakis: Youth, Love and Longing in Buenos Aires Night Life

Julieta Christofilakis used to frequent clubs with her low-tech built-in flash and 35mm half-frame cameras, capturing moments of Buenos Aires nightlife and youth scene that gave life to her early works, “Se lo debo todo al azar” (I Owe Everything to Chance) and “Chapar con mi generación” (Making Out with My Generation).

However, nowadays, the Buenos Aires-based artist doesn’t immerse herself in nightlife in the same way as before. Despite this inevitable change that comes with the passage of time, Christofilakis continues to explore the themes of her generation, albeit with a different focus and atmosphere.

Her latest conceptual work, “Perdí la fiesta” (I Lost the Party), evokes a bittersweet feeling compared to her previous projects. Here, the simplicity, enjoyment, and fleeting nature of parties are replaced by the meticulous recreation of these experiences in the photography studio. Working in collaboration with actors and directing every detail of the scene, Christofilakis attempts to capture the essence of a past lived and enjoyed, now tinged with the melancholy of early adulthood.

During our meeting at a café in Palermo, Buenos Aires, Julieta Christofilakis and I delved into her journey as a photographer. She reflected on themes of youth, longing, and intimacy, and opened up about the challenges of directing and staging these scenes. Additionally, she discussed the conceptual aspects of performance and art direction in her newest work.

Julieta Christofilakis is a photographer and visual artist. She is studying for a Bachelor’s degree in Photography at UNSAM. She is part of TURMA, an educational platform for the production and dissemination of Latin American visual culture. In 2021, she published her first photo book, “Le debo todo al azar,” which won the “Artist’s Books” call (2021) by Museos BA. In 2022, the artist participated with a photographic series “Chapar con mi generación” (2018 – 202) in the 4th edition of the “Beca PAC FOTX” training program by Proyecto PAC (Gachi Prieto Contemporary Latin American Art). This series is the main precursor to her current project, taken at parties with a compact camera with an integrated flash. This production came to a halt due to the mandatory preventive isolation starting in March 2020. It found its end and definitive mutation later on, with the return to “normalcy,” upon realizing that the characters portrayed and the artist herself were at a different stage in their lives, adult, with different interests and fewer shared rituals. In this context, “Perdí la fiesta” emerges, a new stage of homemade image production and research, starting from exercises and certain economic limitations. As a result of this first experimentation, a pre-selection of 17 photos was made, one of which (Untitled. Digital photography. Direct shot in studio. Fine Art. Epson luster paper 260. Black rod frame 2 cm with 3mm glass. 100 x 150 cm, 2022) was chosen to be part of the final collective exhibition “Fábula,” curated by Francisco Medail and Lorena Fernández.

During 2023, the artist continues her training and research on her project in the workshop and group work clinic space “Taller de Prácticas Artísticas,” coordinated by Lorena Fernández. She is currently undertaking the Proyecto Imaginario Latinoamérica, a 17-month-long distance learning cycle for photographers and visual artists, where she received a half scholarship. Since 2015, PI.IMG has been established as an advanced training program for photographers and visual artists. Founded by Martín Estol and María Elena Mendez, with a teaching team that includes various personalities from the contemporary art field such as Eduardo Stupía, Santiago Porter, Mariela Sancari, Diego Guerra, Eugenia Rodeyro, Maria Paula Zacharías, Francisco Medail, among others.

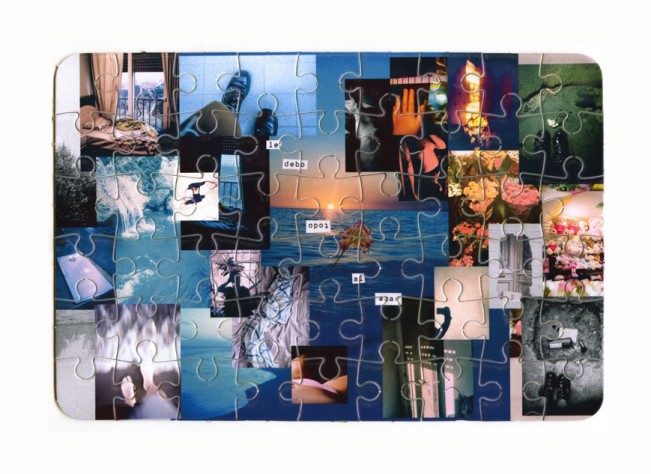

VI: I have in my hands, Se lo debo todo al azar (I Owe Everything to Chance) which is your first book, your only self-published book, and it’s a compilation of this series of photographs you took with a half-frame camera.

JC: I have an obsession with devices in general. So, I did my first work with one camera and then I bought another camera, which is the one I used for this work, and I started doing something else because I changed devices. Like, that happens to me a lot.

VI: So, the device then somewhat governs your process?

JC: Absolutely. Yes, and I work differently depending on which device I use.

VI: And that speaks to your sense of adaptability, also as a photographer.

JC: Of course. So, I bought this camera, which an analog Canon camera with a half-frame where the film or negative is cut in half. So, instead of passing through the entire film frame, it passes through half of the negative and exposes half of each negative of 35 millimeters. So, for each negative of 35 millimeters, it gives you a diptych of two vertical images that it joins in that 35-millimeter negative. So, when you receive the scanned film, you receive all diptychs, you don’t receive individual photos.

VI: And that forces you to think in a specific way, to think in pairs. So, you take some photos and then think about which one will be the companion?

JC: It depends. It depends.

VI: I’m intrigued!

JC: Well, Chance plays a big role there because sometimes you do think about it, and sometimes it goes wrong too because you hadn’t remembered how many photos you took. And the counter doesn’t work properly, like all old analog cameras. So maybe you thought you took a photo of two. Actually, you took the last photo of one pair and the first photo of the next, and there the sequence breaks. But at the same time, there are times when you don’t see two photos, and I don’t, it’s not that by taking one photo, I necessarily look for a pair somewhere automatically. Sometimes I take a photo that I like, a photo as if it were the only one, just from the camera. And I continue living and go back to record it at another moment, until something else catches my attention and leads me to take the camera again. So, sometimes it’s not so linear, and the pairs aren’t put together as thoughtfully as that. Chance, that’s were the title of the project sort of comes from.

VI: How long did you work on this project?

JC: Well, these are photos, if I’m not mistaken, from 2018 or 19. I think it was at the end of 2017, even. I did it for sure until the beginning of 2020 when the pandemic came, and then I stopped taking photos with that camera because the device was no longer suitable for the photos I took of myself at home. It didn’t have a self-timer, it didn’t have anything. So, I stopped using it, and in fact, I never used it again.

VI: Of all the photos you took with this camera, how many made it into the book?

JC: Very few, very few.

VI: The book also has these quotes you can play with.

JC: What I did was look for my diaries after the book, I went to my diaries from ’18 to 2020, from the time of the photos, and I started piecing them together like a puzzle.

VI: Working from your own archive.

JC: Obviously, not all the texts that appear are from my diary. I’ve edited, touched up things, I’ve also invented things. It’s not like it’s all a documentary about these two years of my life, but the texts arise from my writings, from those moments that are years of archives, from others, from my phone, from what I wrote in my chat with myself, from my physical diaries, from everything.

VI: You told me that you started studying photography when you were 15.

JC: I started doing the photography workshop for teenagers in Turma, which is an educational space where I work today. I did that workshop for two years. And then at 17 years old another workshop, one day a week, five hours that was for childhood, youth. I was in the 5th year of high school and wanted to do the program. Many hours of work had to be dedicated to it.

VI: Your projects Se lo debo todo al azar (I owe everything to chance), Chapar con mi generación (Making out with my generation), and Perdí la fiesta (I lost the party) have a lot to do with youth.

JC: Yes, a little, yes. I think I started taking photos of what I knew. When I started taking photos, when I was very young, it was about me, my life, my friends and everything. It is an age that attracts me a lot, adolescence: that moment in which you are old to make many decisions, but at the same time you are too young to make others; that moment when you think you can do everything and then you realize that you were an idiot and that wasn’t the case. Also, independence and not having it completely draws my attention. Many things are still controlled by other people; and at the same time, you think that you are already grown up and that you can decide a lot of things.

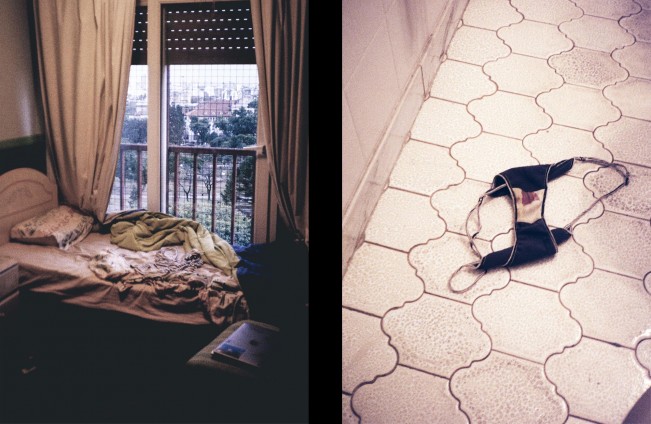

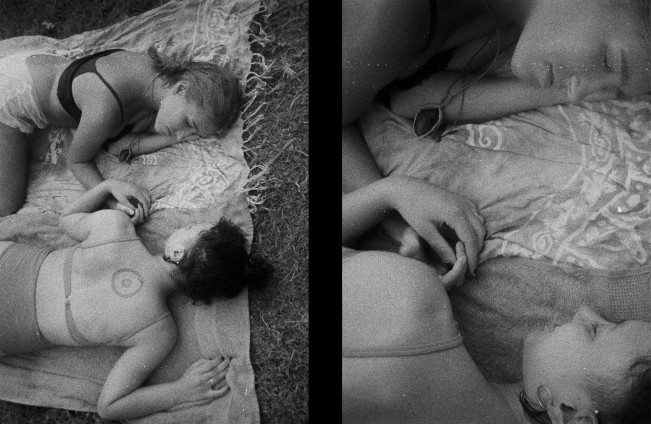

My first two projects, Se lo debo todo al azar (I owe everything to chance), Chapar con mi generación (Making out with my generation), were very focused on the stage of my life. For the latter, the images were taken at parties between 2018 and early 2020 for people in my close circle with a Canon PowerShot camera. The device, which is small and has a built-in flash, allowed me to get closer and record what I wanted to collect: Kisses at parties, conversations in the bathroom, corners where the main light does not reach, the stairs that take you to the terrace, and all those intimate places within the crowd.

VI: A lot of the project was also influenced by love and desire, right?

JC: Yes, I think that adolescence is the time when one discovers oneself and, in some way, also sees oneself reflected in others. There is something about this process that has always fascinated me; my tendency to observe those who love each other, desire each other, care for each other in a way that could be considered romantic and even corny. I have always believed fervently in love, which, I admit, paints my vision of the world and my personal life in idyllic tones. I find myself constantly observing expressions of love and desire, and I consider adolescence to be a period full of these discoveries, which makes it endearing. Seeing teenagers showing affection to each other fills me with tenderness even now. It is not easy to perceive the essence of being a teenager while living, but when observing it from the outside, yes, and I think it is a sensitivity that I have maintained to this day.

I believe that adolescence, seen through my lens as a photographer, is characterized by a constant emotional quest, not devoid of dangers. It is a stage defined by the intense desire to feel, to expose oneself to both positive and negative emotions, in a pursuit of experiencing profound sensations. Adolescents tend to seek refuge among themselves, distancing themselves from the family environment to live experiences they deem extraordinary, driven by the belief that outside of home, away from the parental supervision that inspires fear, they can fully experience life.

This constant search for new experiences leads them to gather together, longing to discover something novel. I find a particular allure in this aspect, especially evident in parties, spaces where it seems that anything is possible, where the unexpected can happen at any moment without certainty of when it will end. Although all parties may appear similar, there is always the expectation that this time will be different, that something incredible is about to occur. It is this blend of illusion and, not necessarily disillusionment, but the sense that anything is possible, akin to a fantasy of disillusionment.

VI: Now you remain interested in these themes but you’re working in a completely different way. In Perdí la fiesta, you mention that “the characters portrayed in Chapar con mi generación and yourself “were at a different stage in their lives, adults, with different interests and fewer shared rituals,” which led you to recreate those moments in a studio set.

JC: What happened is that Chapar con mi generación came to a halt, as we say. I used to go partying with friends and couldn’t capture the photos I used to take before. I no longer inhabit those spaces, I don’t go out as I used to, my friends don’t look at me in the same way. I realized that I had lost the intimacy I had with my friends at that time. The intimacy I have now is different because we have grown up and now we live together and each one has their own things, their own time, and their own parallel lives. At that time, adolescence, friendship was the central focus of our lives.

VI: And how did that play itself out in your creative process?

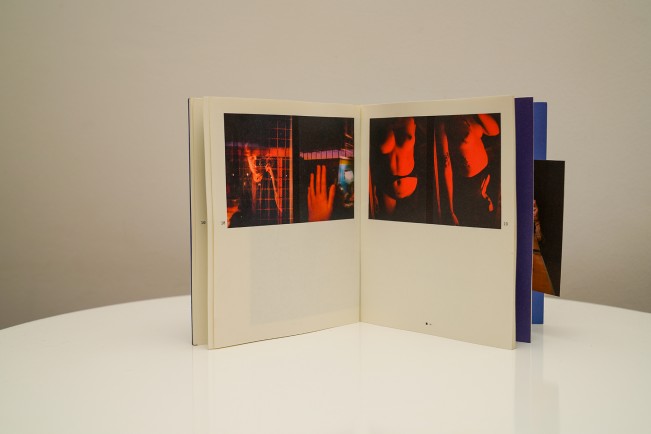

JC: Perdí la fiesta is the most conceptual project I have done, focusing on representation, performance, and art direction, in which I work with friends and actors to recreate these moments. There was an organic evolution from no longer being a teenager immersed in this space to recreating them for the camera in the studio, a bit as evidence that it was no longer possible, that it had become a fabrication. I lost the framework, I lost the context, I lost the party, and I even lost my camera, which was small and had a built-in flash. The party that lasted 6/7 hours once or twice a week turned into an endless white in my house at 5 in the afternoon. There’s no longer a bathroom, stairs, terrace, or dance floor. Two studio flashes, one on each side, gossip, kisses, and dances, all directed. In the project, I’m working in front of a white background with actors who can understand the situation I’m staging and convey the sensations or feelings or situations I want to express. So, more like a directing process in the end, it’s also more like a collaborative process with the people who are recreating these scenes.

VI: Now, what has been a challenge for you? Re-creating all these scenes in a set?

JC: Everything. It is also hard to direct people, finding the right movements, it’s something that I am doing for the first time. I have a lot of mixed feelings about the performance aspect of it because it attracts me a lot and at the same time I am very aware that the performance is meant to be seen in one place and experienced there and then disappear and that’s it, and I’m doing the complete opposite, which is to document these party recreations on a set.

VI: I can’t wait to see where this project takes you and how your process evolves.

Installation view of Untitled. Digital photography. Direct shot in studio. Fine Art. Epson luster paper 260. Black rod frame 2 cm with 3mm glass. 100 x 150 cm, 2022) at the collective exhibition “Fábula,” curated by Francisco Medail and Lorena Fernández.

Installation view of Untitled. Digital photography. Direct shot in studio. Fine Art. Epson luster paper 260. Black rod frame 2 cm with 3mm glass. 100 x 150 cm, 2022) at the collective exhibition “Fábula,” curated by Francisco Medail and Lorena Fernández.

Vicente Isaías is a Chilean multimedia artist working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence. His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him an Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a photography jurying position at the 2023 Alliance for Young Artists & Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region. His work has been exhibited most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications. A cultural worker, he has interviewed renowned artists and curators and directed several multimedia projects across various museum platforms and art publications. He is currently a content editor at Lenscratch Photography Daily and Lead Content Creator at the Griffin Museum of Photography. He holds a BA in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he received a Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and a Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography.

Follow Vicente Cayuela on Instagram: @vicente.isaias.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Lee Gap-Chul: Conflict and ReactionJanuary 14th, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026