Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes Efstathiou

n expanding our celebration of Earth Week, Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers will focus on the work of Eco.Echo Art Collective, a group of international artists deeply concerned with the well-being of our planet beyond human needs. The group’s concerns are climate change and anthropogenic activities’ global impact. Driven by an appreciation for the natural world’s beauty, diversity, and wonder, they believe in the inherent worth of all living beings regardless of their instrumental utility in fulfilling human desires. This week, members of Eco.Echo Art Collective will take time to reflect on each other’s work and how the transformative potential of photography can engage in challenging conversation and affect social change around ideas of humans and our surroundings.

Today, member Josh Hobson will share his discussions with member Kes Efstathiou.

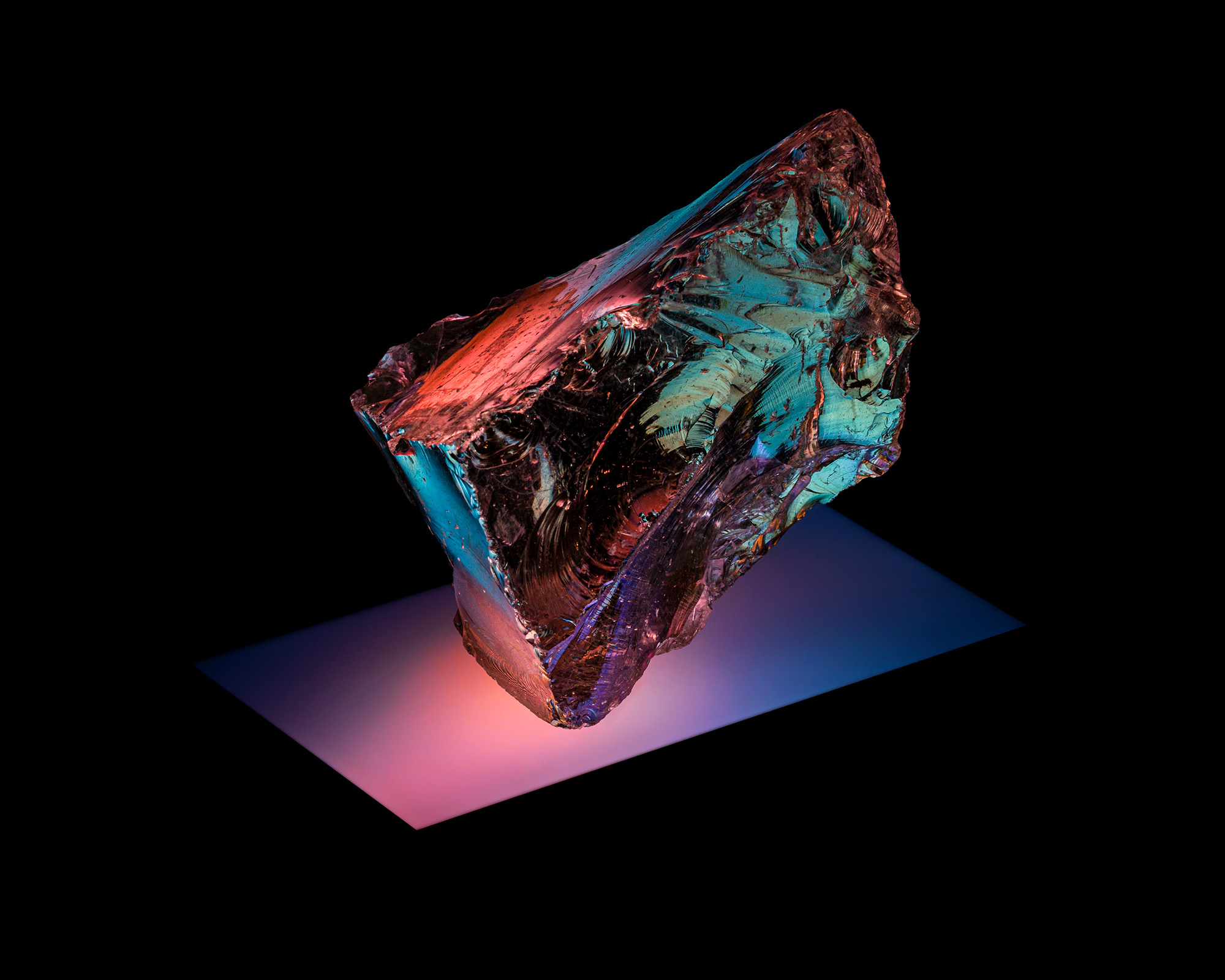

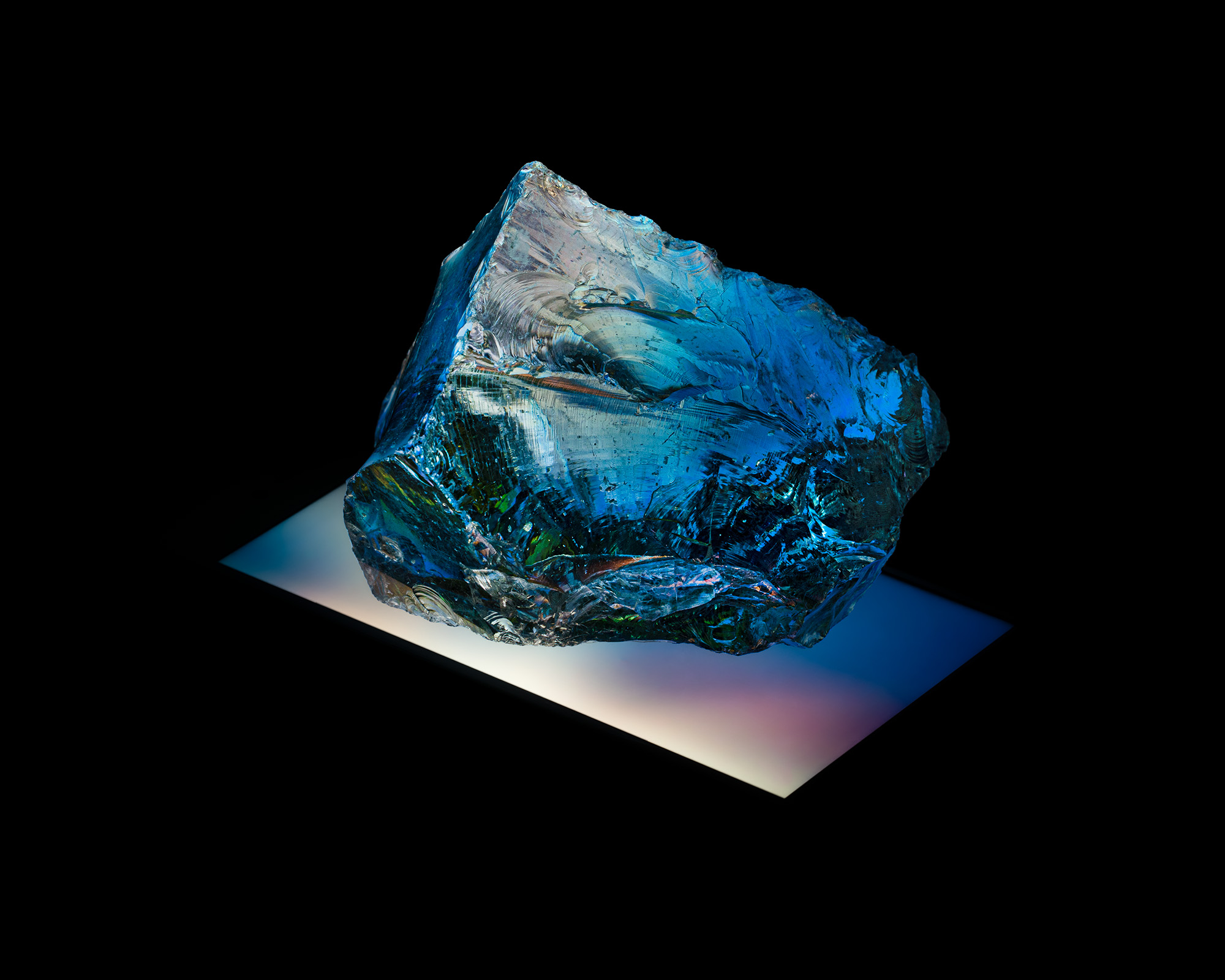

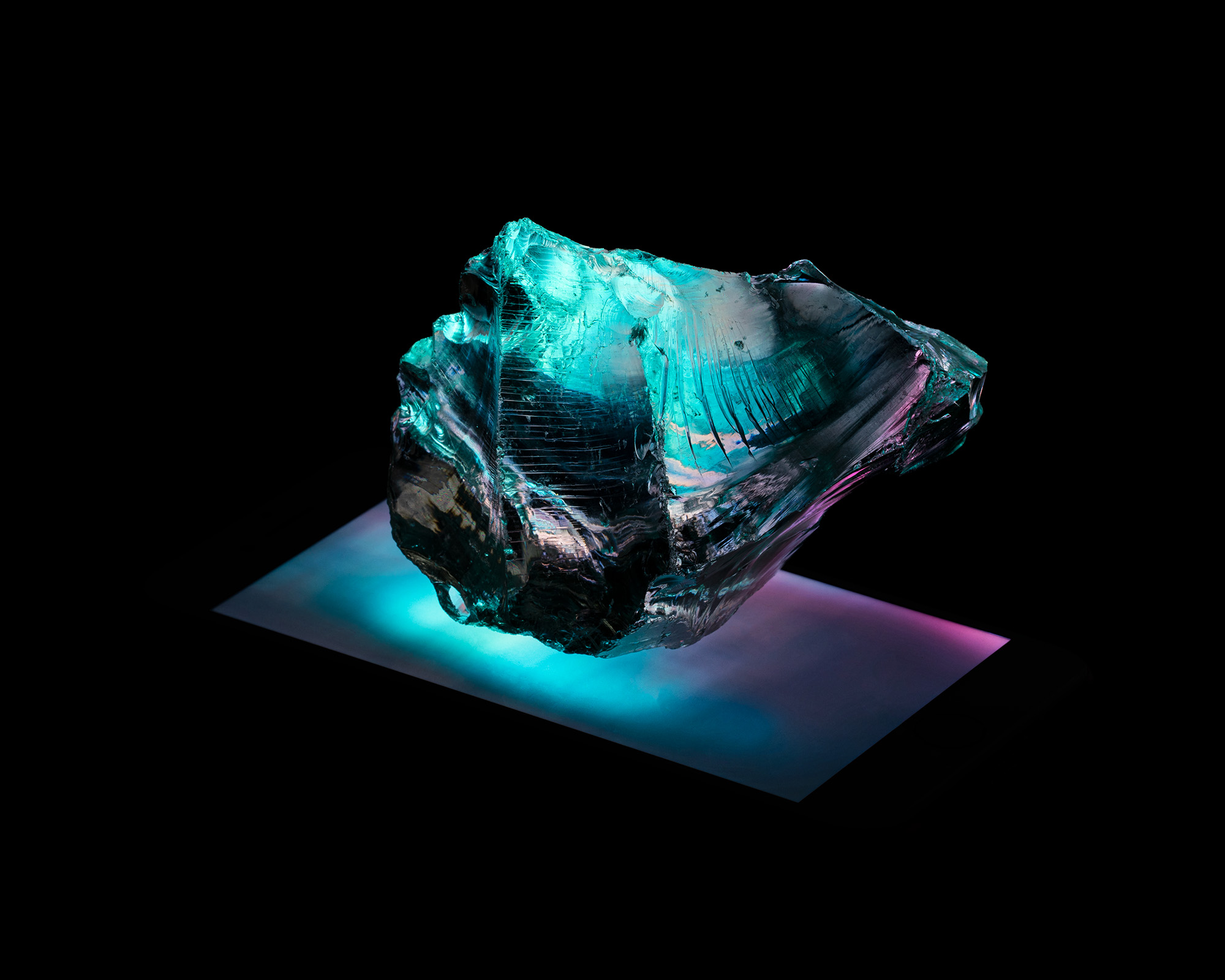

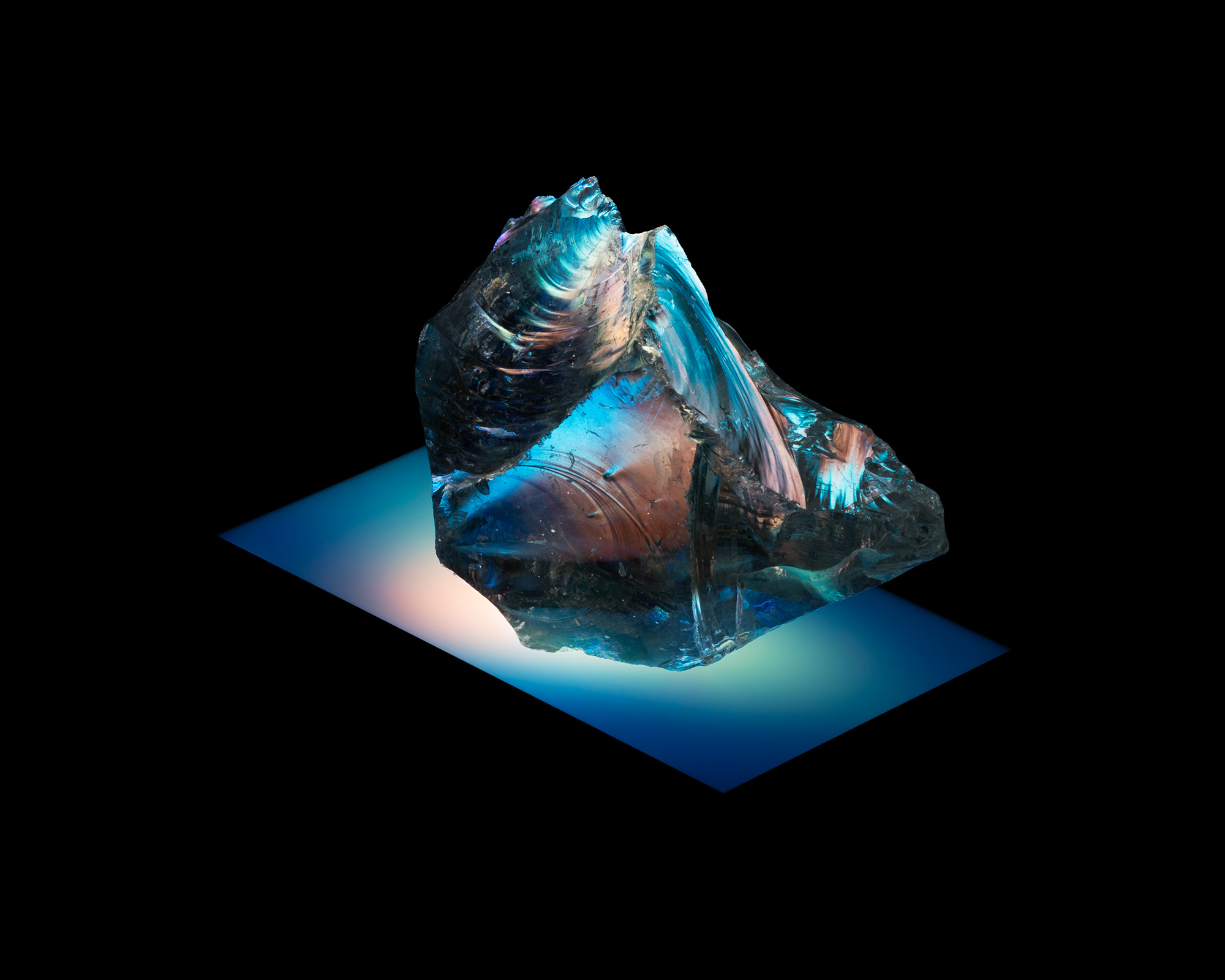

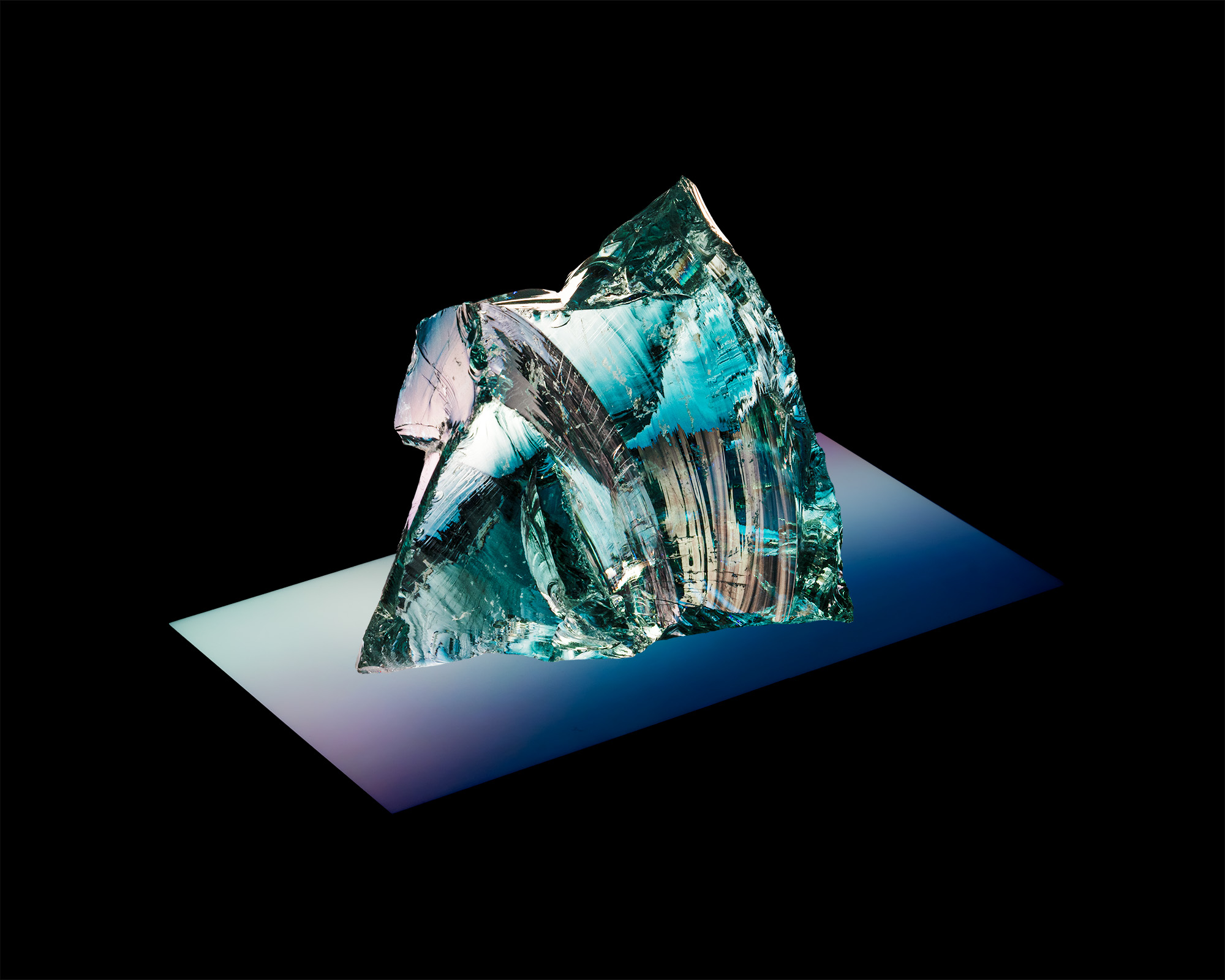

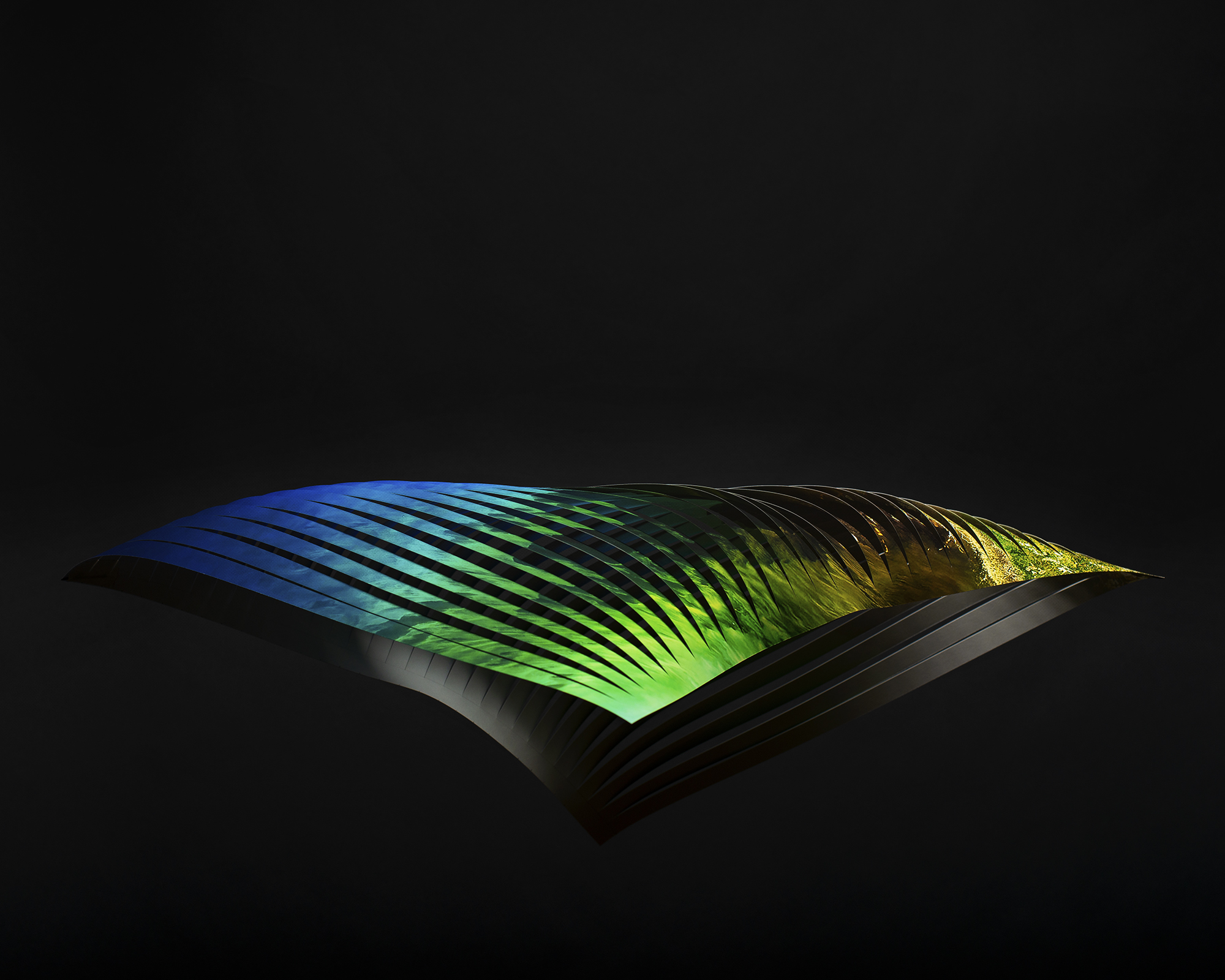

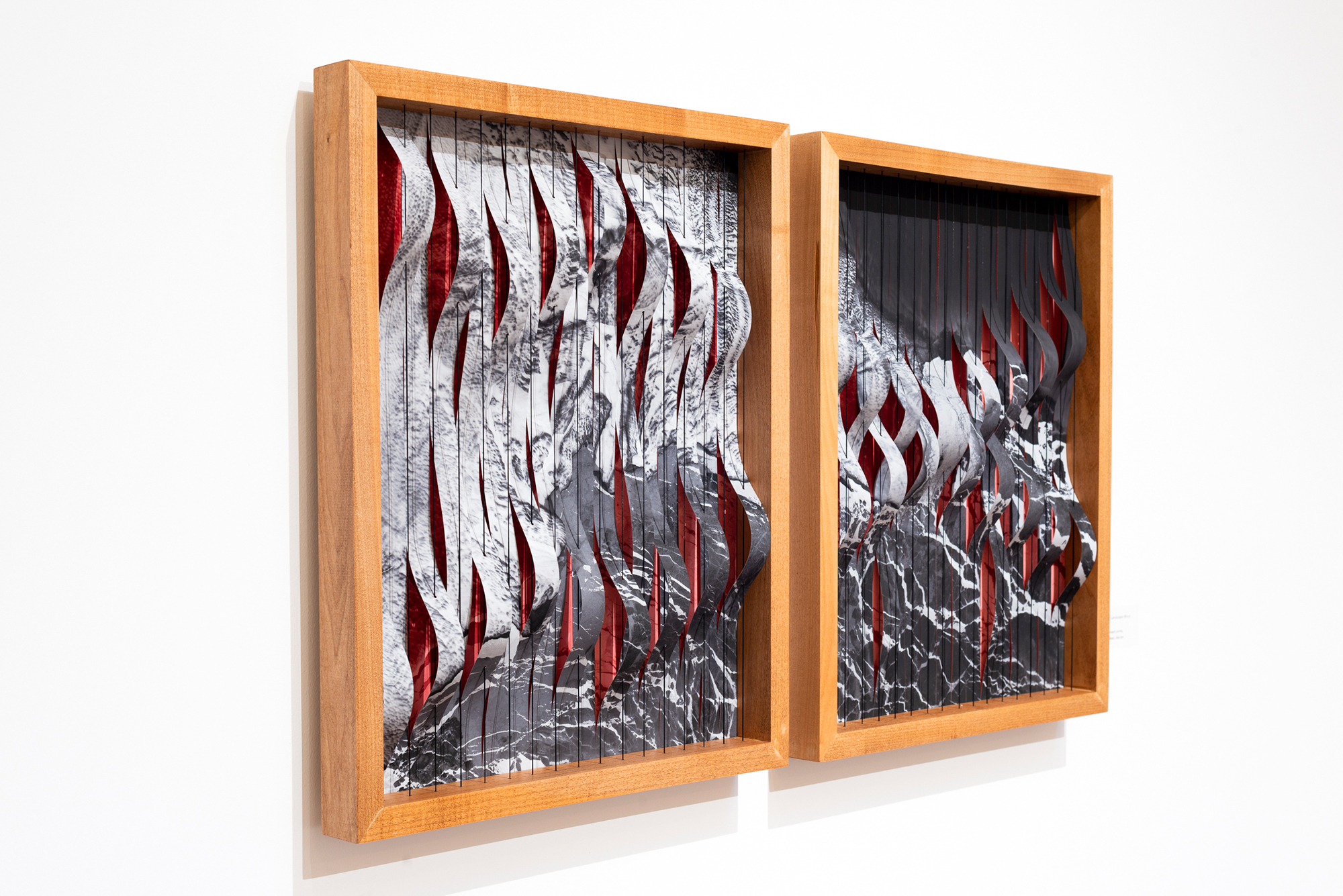

Kes Efstathiou’s new series Ice is a potent work that explores eco anxiety and how a relationship to the environment mediated by technology can both ease and amplify this experience. His studio-based works and resulting installations engages in the tradition of landscape photography through an evocation of the sublime but does so by centering the distance and disconnection inherent in our contemporary relationship to the land.

We are often disconnected from the results of our individual and collective actions. For many, the most dramatic effects of climate change are quite distant but brought close via our devices and highly networked world. Efstathiou seeks to draw attention to the complicated role that technology, and specifically our screens, play in our current understanding and reactions to climate change. Individuals have never had so much information about the state of the world, but with so little agency to effect the dramatic changes that are needed.

This paradox lies at the core of the eco anxiety that many of us grapple with daily. Efstathiou’s work, and especially the series Ice leverages this tension to great effect, creating deeply evocative, impactful, and frankly beautiful work. But behind the polished veneer of impeccable studio lighting and bright, saturated colors lurks an unsettling truth that cannot be ignored.

Josh Hobson: I’d like to start by discussing your series Ice. How did this project develop? How does this work express the theme of ‘eco-anxiety’?

Kes Efstathiou: In 2016, I took a trip to Alaska with my mom. On a boat tour, a guide handed me a softball-sized chunk of glacial ice that she had lifted out of the water. It was very cold, very clear, and very beautiful. Fast forward to 2021, having already established a love for fake nature, I went to Michael’s seeking inspiration from the “plant” section, where I picked up softball-size chunks of clear glass that brought my mind immediately back to this surreal memory in Alaska.

By illuminating the “ice” with the phone screen, I hope to draw attention to the complicated tool that simultaneously informs while causing anxiety. From my personal mental health perspective, being unaware is just as detrimental as being aware; it doesn’t feel like a choice.

JH: This anecdote makes me think about distance and disconnection. Both appear to be themes in your work. Can you speak to this? How are you formally and conceptually utilizing these themes?

KE: I am using “ice” as a symbol of climate change because that is what I grew up with. In the early 2000s, polar bears dying and glaciers melting were the most common concerns. Through the lens of a teenager growing up in East Coast suburbia, the climate crisis seemed disconnected from everyday life, learning about it every few years in a science class or a National Geographic documentary. We didn’t have social media and constant reminders warning us about the bees dying, prevailing forest fires, and the microplastics in the ocean. We had Wall-E (probably the only PIXAR movie that won’t have a sequel), The Bee Movie, and Happy Feet. It was more like, “Hey, turn off the water while brushing your teeth.” Now it’s like, “I am going to remind you every day about a new disaster wreaking havoc on the planet, and I am going to blame corporations but also the individual’s choices.”

The installation animates from positive to negative for several reasons. One reason is that this conversation is nuanced. I don’t have answers for myself or fully resolved feelings. I have been trying to elevate gray areas and indecisive thinking in my work. Leaning into motion has been helpful, as it speaks more to fluidity than a photograph.

JH: In Ice, the digital mediation of the natural world through our devices is conveyed by the inclusion of screens in both the images and installation. For you, what is the role of the internet, and more specifically social media, in our experience of landscape and nature?

KE: I started conceptualizing this work during a longer environmental awareness moment on social media. These posts inundated my brain with guilt and transformed every mundane decision into a hyper-conscious choice. I hit my threshold after seeing the same content endlessly reshared for a few days. The same week, an art news outlet celebrated a photographer traveling to Antarctica to document disappearing glaciers while shaming those who created NFTs for causing a carbon footprint. Through this, I became more interested in how eco-conscious artists, including myself, justify making and managing anxiety. Rather than drawing attention to the climate crisis, I am much more interested in exploring the gray areas that are hard to discuss and the psychological toll of this constant, unfiltered awareness from social media.

JH: This is something that I grapple with a lot in my own work. How do you justify making the type of work that you do? How do you manage the associated anxiety? Are we perhaps framing this in the wrong way?

KE: At times, these concerns have stunted me from making anything, regardless of the conceptual idea. I finally realized my peers, students, and idols continue to make and put work into the world and have success stories. I didn’t want to be left behind anymore, and not creating only made it harder to manage my anxiety. That is why I am interested in examining artists’ anxiety and headspace instead of framing it specifically in the context of climate awareness.

These are my pro tips for managing anxiety: Exercise, limit time on the social media dumpster fire, and go outside. I also started reading books to consume more productive and researched information. I would recommend Ways of Being by James Bridle and Nature’s Best Hope by Douglas W. Tallamy.

JH: Your work is both formally and thematically related to the landscape. How do you articulate your thoughts on the tradition of landscape photography through a studio-based practice?

KE: I am interested in Thomas Albdorf’s book General View, where he guides viewers through a trip to Yosemite from his European studio. I like this idea of something being imaged in such great quantity for such a long time that the proxy becomes potentially more authentic than the “real” experience. Someone may not even need to travel to have the experience of being present in a space. The studio setting allows me to recontextualize traditional approaches to landscape photography that address the contemporary ways we consume images.

I lack patience and love having full control, so although I am a sucker for making beautiful landscape photographs, the studio draws me in. My studio practice came out of necessity. After living in the West for several years and returning to the East Coast’s brown winters, I wasn’t ready to abandon photographing the sublime. In many ways, the studio parallels my experiences outdoors. It is an active space where I continuously learn, and the simulation can be just as fun to explore.

JH: I love that you mentioned that the shift to the studio was not just a conceptual one, but one of necessity and practicality. Parameters and limitations are so important to the practice of many artists. Do you actively consider limitations as features of your practice?

KE: I love this question, but I wish I were better at limiting myself. Photography is so expansive, and I am curious about its endless possibilities and overlapping technologies. My only real parameter is that I will always work digitally, as I prefer to avoid being in the darkroom and scanning negatives. I am interested in embracing my humble photographic beginnings with the GameBoy camera, Pokemon Snap, and screenshots from The Sims.

JH: Your work seems to be leveraging the visual language of advertising and marketing. Is this intentional and strategic?

KE: I started elevating my toolkit with strobes, compositing, video, etc, to become a better professor. I want to demystify technology, open up career opportunities, and help my students become stronger artists; this has been the best gift teaching has given me.

Through this teaching=learning process, I became deeply interested in how advertisements are constructed and function. While thinking constantly about the algorithmic ads that sell me products under the guise of being eco-friendly, I also watch endless videos of folks lighting, compositing, and retouching product images for commercial use. I apply this knowledge to my subject matter, which has been an incredibly enjoyable learning process. I wouldn’t normally state this, but the still “ice” photos are all 3 to 5 images composited, which I learned how to do while watching a video of a YouTube bro demonstrating how to combine different exposures in a perfume ad.

In this work, I am thinking about the promised future conveyed through the 80s neon wave aesthetic. Like marketing’s goal, the promised future was all about control and desire, and maybe I hoped technology would outperform the environment.

JH: You very unapologetically want to make beautiful images. What is the role of beauty in your work? How does beauty function when addressing such distressing topics?

KE: I am only recreating what has naturally occurred in the landscape: glacial caves glow teal, northern lights decorate the sky, and light descends into deep water. People can hold two things at once. Something can be beautiful and distressing simultaneously. Social media can be a tool for problematic misinformation and productive communication. Artists can work with a clear stance while exploring unknown thoughts and feelings.

Kes Efstathiou is a photographer and educator who entered the medium at a young age via GameBoy Camera. Decades later, he weaves the physical and digital together to address the self, technology, and, more broadly, the photographer’s inescapable role in altering our perceptions. Kes’s practice of constructing for the camera is an underlying metaphor for his identity as a trans-man. Kes actively seeks to challenge and expand the institutional expectations of underrepresented artists. He received his MFA from Rochester Institute of Technology and BA from Montana State University—Bozeman. Kes is a Visiting Assistant Professor and freelance photographer based in Fayetteville, AR.

Learn more about Kes’ work on his website, https://www.kesefstathiou.com/ on Instagram: @kes_efs.

Joshua Hobson is a lens-based artist and educator based in Spokane, WA. He studied photography at the University of Florida and received a BFA in Creative Photography in 2007 and an MFA in 2017. Josh regularly exhibits his work including exhibitions at Candela Books, Colorado Center for Photographic Art, Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography, Newspace Center for Photography, Chase Gallery, Saranac Art Projects, Brooklyn Waterfront Arts Coalition Photo Center Northwest and the Center for Fine Art Photography. Josh is currently a lecturer and gallery director at Eastern Washington University. Josh’s work is engaged with an analysis of, and experimentation with the fundamental attributes of the medium. His practice incorporates tabletop studio photography, on-site photography and camera-less concrete processes. Through material engagement and process-oriented actions Josh’s work aims to shed light on the various uses and origins of the photographic image. His work is grounded in material culture, the history of abstraction and an alternative history of lens-based media. His current projects engage with the dire environmental issues facing the planet including both the social and personal effects of climate change, pollution and resource extraction.

Learn more about Josh’s work at https://www.joshhobsonstudio.com/ and follow him on Instgram: @joshhobsonstudio.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026