The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Joseph Ladrón de Guevara

It is with pleasure that the jurors announce the 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner, Joseph Ladrón de Guevara. Ladrón de Guevara was selected for his project, Love Amidst Mortality , and is currently attending the Dirección de Proyectos Visuales y Fotografía – Visual Projects and Photography Direction Centro de la Imagen Lima – Perú. The Honorable Mention Winner receives: $250 Cash Award and a Lenscratch t-shirt and tote.

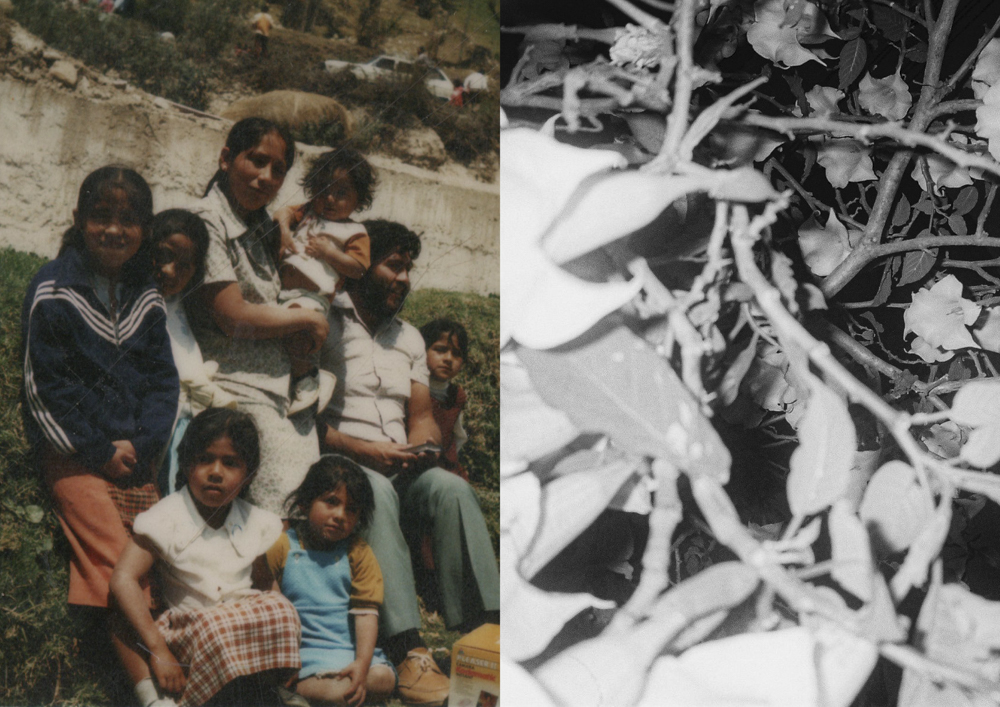

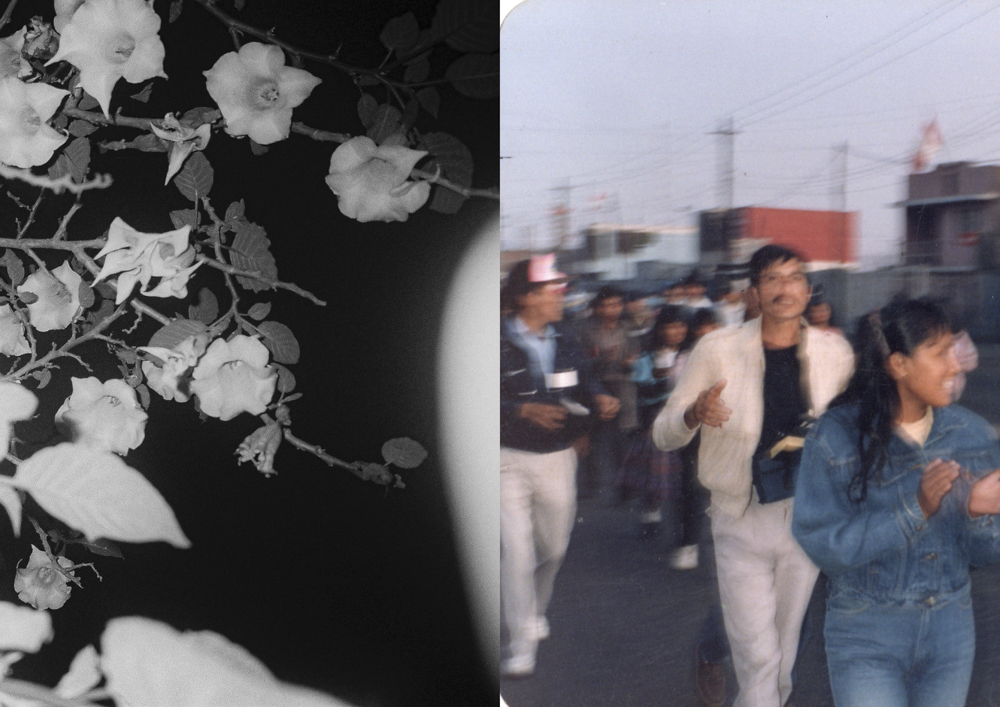

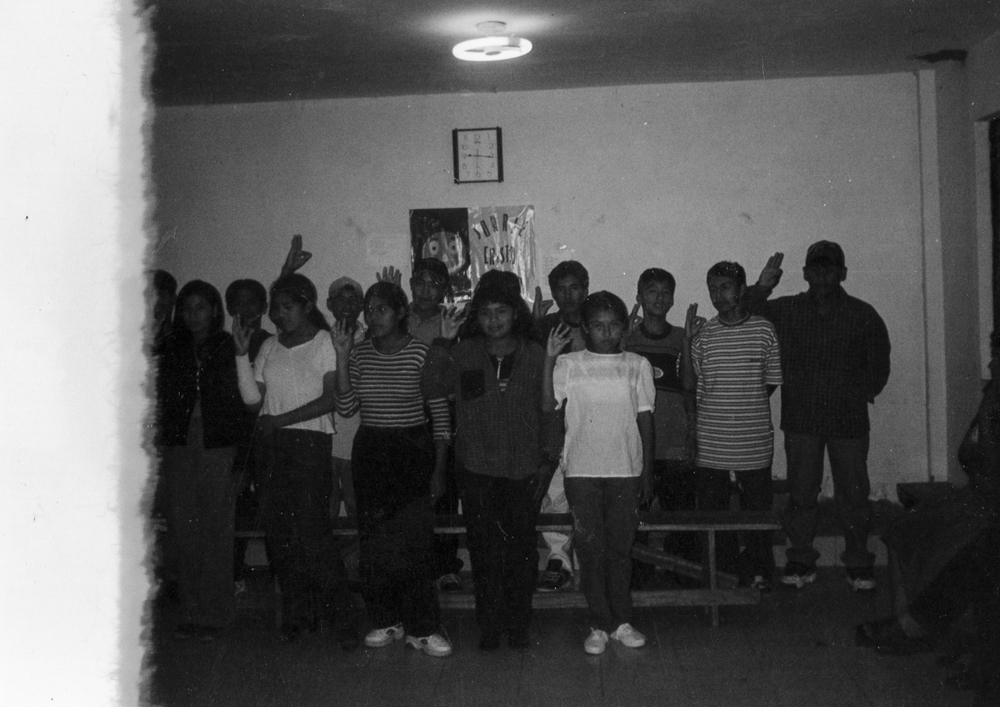

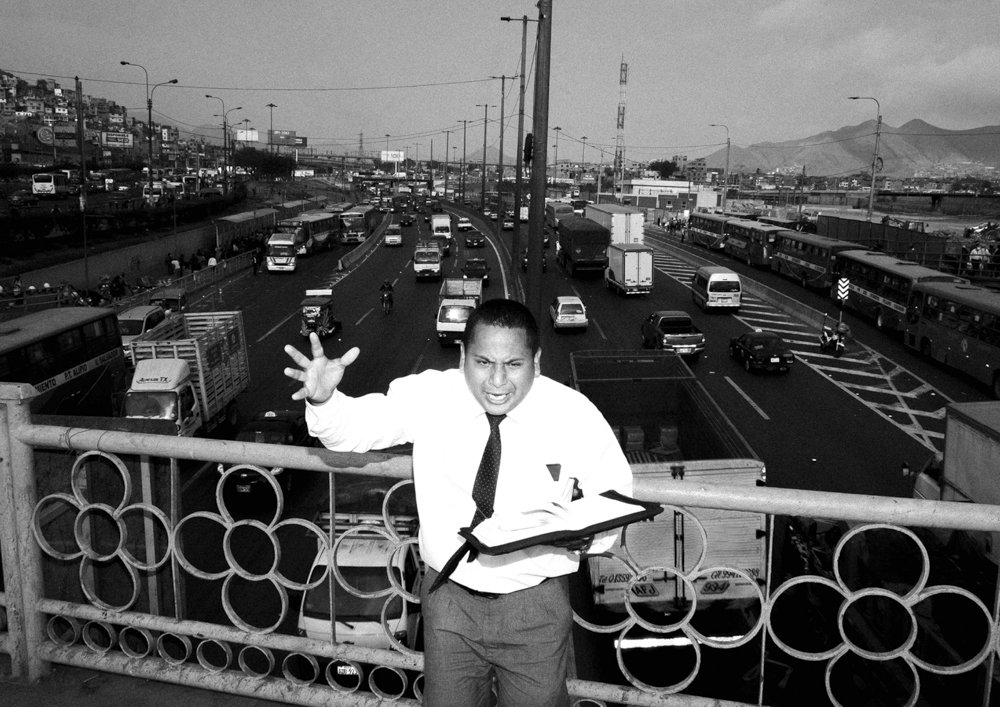

Love Amidst Mortality is a photographic elegy seeking illumination on the limits of faith and human freedom. Inspired by the life and death of De Guevara’s grandmother, Julia, the project is built on the artist’s emotional and ideological conflicts with her decision to forgo cancer treatment. The scale at which he makes us look into her life is both intimate and panoptical, oscillating — at times frantically — between vehement street photographs of public preachers on highway crossings, archival photographs of communions and baptisms, and serene nature scenes that mirror the more transcendental aspects of spirituality. These broad vantage points coalesce beautifully in an incredibly sequenced project thanks to the artist’s archival acumen and photographic sensibility. “A clash between calm and chaos,” as the artist puts it, De Guevara dissects the interplay between religion’s public spectacle and its more intimate, personal and familial truths. Throughout the project, De Guevara’s lens wanders extensively, surgically scrutinizing the moral networks imprinted by our beliefs — and how we build our lives and deaths around them. — Vicente Isaías

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, Independent Writer, Editor, Curator, Former Publishing and Awards Director; Senior Editor, CDS Books Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Samantha Johnston, Executive Director of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

Joseph Ladrón de Guevara (1996) is a lens-based artist, photographer, and visual storyteller born in Pisco, southeast Perú, and currently based in Lima. He has studied for a degree in Mechatronic Engineering from the PUCP, and is now pursuing a degree in Visual Projects and Photography Direction from Centro de la Imagen, both in Lima.

Joseph’s work addresses themes such as identity and territory, through explorations with photography and archives around different social places ranging from Christian faith to hip hop. Now he visually investigates the public sphere, in relation to concepts such as subcultures, simulacrum, and social opacity.

He won the New Generation Prize of the PhMuseum Photography Grant 2023 and was a finalist for the I Paco Casanova Grant 2024, by EFTI. Selected artist in Vogue Magazine’s Panorama Latino Americano 2024 open call, and a VII Photo Foundation alumni. His work has been exhibited in the 2023 edition of Verzasca Photo Festival, Jakarta International Photo Festival, and PhMuseum Days. His work was also part of the exhibitions ¿Bailamos? by Cuarto Oscuro magazine, Mexico City; and FETISH, by ZONE and 2xMuse, Vercelli, Italy.

Follow on Instagram: @josephlgc/

si el sol llegara a oscurecer, y no brille más (2023)

Surely he took up our pain

and bore our suffering,

yet we considered him punished by God,

stricken by him, and afflicted.

Isaiah 53:4

Julia, my maternal grandmother, died after battling cancer for a year. She decided not to treat her illness, as she firmly believed that her god would heal her. The end of her life, always marked by the Christian faith, took place while she was singing her favorite choir, surrounded by the whole family.

Her death, the repercussions it caused in my family, and the heavy feeling of absurdity that her blind faith imprinted on my understanding left me with many emotional conflicts and ideological concerns, which have been finding her answers in the development of this job.

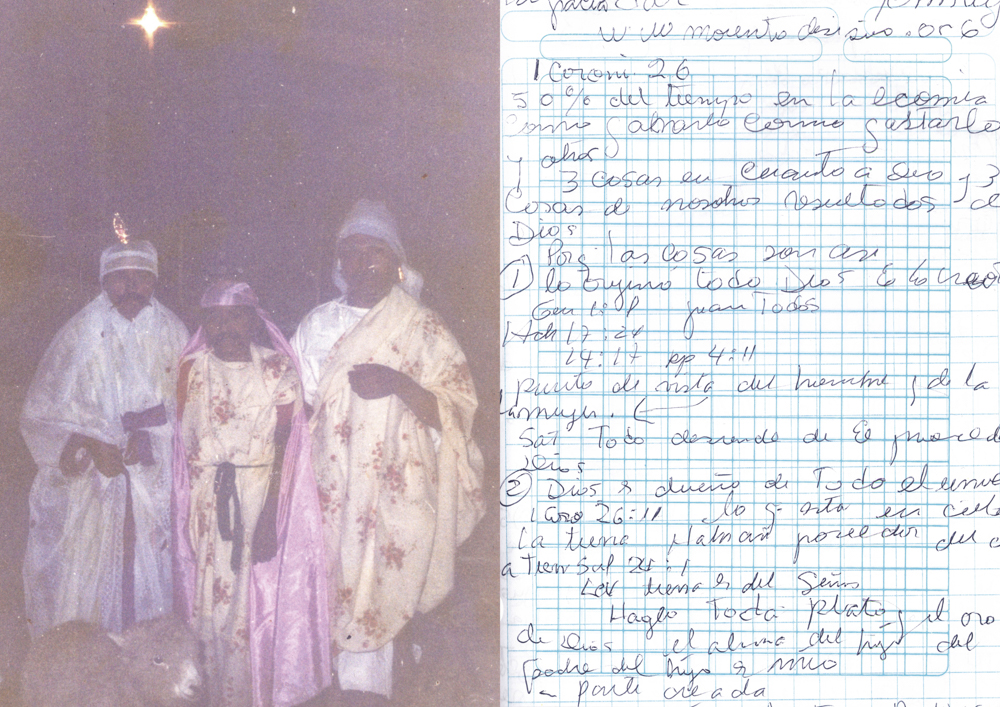

Making use of visual resources such as the family photographic archive; pieces of writing from my grandmother’s last diary; documentation of its congregation and nature photographs, a visual narrative is created, one that addresses loss and acceptance, while offering an intimate approach to the Christian faith, its vicissitudes and the way of thinking of its believers: sometimes complex and radical, but other times beautiful and hopeful.Through these images I propose the confrontation with the feeling of absurdity that invaded me when I saw my grandmother’s decision, but also with those small episodes full of hope that appeared in the middle. This conjunction has led to the understanding that it was not just an act of faith, but an act of love. Every act of faith is, on some level, an act of love.

As someone raised in a strongly believing family—and through symbols drawn from my personal experience and vision, which seek to resonate universally with diverse beliefs and spiritualities—I seek to offer a realistic view of the subject, but not one that acts as a typographical mirror of what happens, but as an alchemy that reveals its causes, its drivers, the reasons that lead people to give themselves to faith, to live it and die it, as my grandmother did.

I use the image to explore the limits of those spaces, tangible or not, that human beings generate and cohabit. Driven by projects that emerge from inevitably personal and intimate interests, I have embarked on the search for visual narratives that demonstrate the need of human beings to question their common spaces, to interpellate them at different levels and forms: to inhabit them.

Oscillating between the documentary and the artistic, and making use of various types of visual language, my work addresses topics such as memory, identity and territory, by delving into stories that are transversal to my individual experience, my personal questions, and the social imaginary.

At the soul of my artistic pursuit lies the exploration of the human condition. With strong roots in the imaginary that constitutes my identity, linked to the religious, but also to the urban, my work moves between the kinetic and the static, the sacred and the ephemeral. I am moved by the desire to crystallize the intimacy of shared experiences, to extrapolate and transmit them through mutual identification. – Joseph Ladrón de Guevara

Vicente Isaías: Congratulations on being an Honorable Mention at this year’s Lenscratch Student Prize! I am thrilled to see more and more photographers from Latin America being recognized for their work. Growing up in Peru, how did the broader society impact you throughout your life? In your artistic journey?

Joseph Ladrón de Guevara Coca: Thank you so much! It is an honor for me to have been selected for this contest.

I also think it is vital that the visual work of us, Latin Americans, and that of visual creators from the global south, in general, be seen more and more. It is a task that we must continue to pursue, the decolonization of the visual arts.

Growing up in Peru, a country that went through a process of colonization, and that continues to be in the shadows in many aspects, and backward in many others, has definitely had an impact on my life and my artistic practice. However, this structurality occurs not only at the global level but also at the country’s internal level. Peru is a country that is too centralized. I was born and raised in Pisco, a southeastern province, and it was not until I migrated to Lima, the capital, that I discovered many things in its metropolis dynamics that I would not have known in my homeland. Photography as an artistic expression was one of them. Then, in the process of getting to know photography in its entirety, there was interference from outside the country, and from local authors who also explored that area.

I also believe that the process of adapting to the speed of life in the city, coming from a very calm province, also had a considerable impact on my life and my path towards art. This duality is reflected in various moments of my photographic work and my life, in general. In the project we will talk about this is particularly visible: there is a clash between calm and chaos, between stillness and the vociferous and desperate movement.

VI: Now, let’s begin by having you tell us more about how your grandmother’s decision laid the premise of your project. When was the tipping point in which you decided, “this is something I want to explore artistically,” and what was the first ethical dilemma you encountered?

JL:In reality, all the visual work on this project was done on a deferred basis, approximately a year after Julia, my grandmother, passed away. During the year that her illness lasted, I was already doing photography, but I didn’t consider the possibility of facing the situation through photographic practice.

The process of her diagnosis and illness was complicated for my family and me, and at that point, I decided that I was not going to take it on with a camera on my face. During that time, without knowing it, I was photographing the issue as a catharsis, but looking towards nature and the city. The visual project did not yet exist as such.

What triggered the first notion of a project was reading her notebook, several months after her death. Reading these texts brought me closer to questions that, later, through visual research on the theme, I would unravel and, perhaps, answer. However, all the visual exercises I developed were attempts to confront it through the image and were not yet thought of as part of a project.

Now, looking back, I could say that the project discovered itself little by little, as it went along. Since the visual approach to the topic and the decision to define it as a project were late and progressive, the most obvious ethical dilemmas, such as that of doing pictures of the disease process, had already been discarded, and those that appeared occurred more forward, in the compilation and editing process.

VI: Was this the first time you experienced the loss of a loved one?

JL: Yes. My grandmother’s death was the materialization of one of my oldest questions. Death had been a recurring concern in my life. When I was 10 years old there was an earthquake that meant that, in my hometown, we lived with death for months. Although no one from my closest core died in that disaster, a concept of death linked to the violent, fragile, and ephemeral appeared to me. This was contrasted with the concept of death that I received from an evangelical upbringing, which was rather that of a transition towards eternal life, that of the end of the race of faith.

This contrast crystallized as a powerful question when my grandmother’s illness appeared. She was the emotional center of the entire family, the nucleus, the sun that we all orbited. Diagnosing her illness was very difficult. Her death, a powerful episode for all of us. Because of the way it happened, while she was singing; for what it meant to lose it for each one; and for the great act of faith and tenacity that her illness meant.

VI: I am interested in knowing, how did you feel revisiting family archives and your grandmother’s notebook for this project? Was there something you learned about her that you didn’t know before?

JL: The first material I reviewed was his notebook. There were a series of reflections that she wrote during the process of her illness. These talked about faith, about the way to live a life that seeks eternal life; of the family. Of death as a near moment. All of them reflections that shaped the conceptualization of this project, and enriched its lines of research.

This reading made my own questions about these topics more intense and made me feel necessary to go to the family photographic archive to look for answers in them. Since its compilation, which involved reviewing them together with those relatives who kept them, there were many discoveries, talks, and memories: the image of Julia and her status as the nucleus of the family became increasingly clear. The life of faith that she led was not just what I knew, it came from the beginning of her life. Since the review was about her, I understood much more about the life she decided to lead, the love she selflessly gave, and her decision.

At the same time, I began to recognize myself within all these questions, to decipher how those family and emotional ties placed me in the face of faith, death, and fragility. That led me, in trying to understand my grandmother’s decision, to investigate the Peruvian evangelical faith, to find the reasons that lead people to give themselves over to the faith, to live it and die it, as my grandmother did.

VI: How did these materials shape the narrative of the series in terms of sequencing and the progression of the story? Is there a beginning or an end?

JL:The first form of visual representation that existed in the project was collage. Using the formats that existed at the time, namely, pieces of writing and archival photographs, I generated assemblages that explored the questions expressed by my grandmother in the notes, through images from the family archive. This gave rise to an editorial logic, which resulted in the first conception of the project being in the form of a fanzine/photobook. It is worth mentioning that all these experiments happened as visual exercises and as a way of facing this theme through the image. The project did not yet exist as a concrete idea, I was approaching it instinctively and intuitively.

This aligns chronologically with my search within the photographic field. At that time, I was not yet studying and I mostly did documentary and street photography. That was my only way of understanding photography and images. That led me to explore the topic from a documentary perspective for a while. Located in Lima, several hours from the land where my grandmother lived and died, I investigated the topic by meeting people who lived their faith in the face of the big city, in its viscera. In a way, that was my way of graphicizing what my grandmother’s decision and all the existing questions meant to me. The image was helping me find answers and get in front of the topic.

This stage of the project was the one that rounded out a panoramic view of all the explorations I had carried out, and was the point at which I decided to definitively propose it as a visual project. Here I started collecting all the material, and imagining possible connections and possibilities between them. From the notebook I took the format, which was proposed as a notebook from that point on. Sequencing had its origins in the first experiments I did with collage. In them, I had made a timeline of my grandmother’s life with some of the texts from her notebook and images from her archive. This was the backbone of the story, from the beginning.

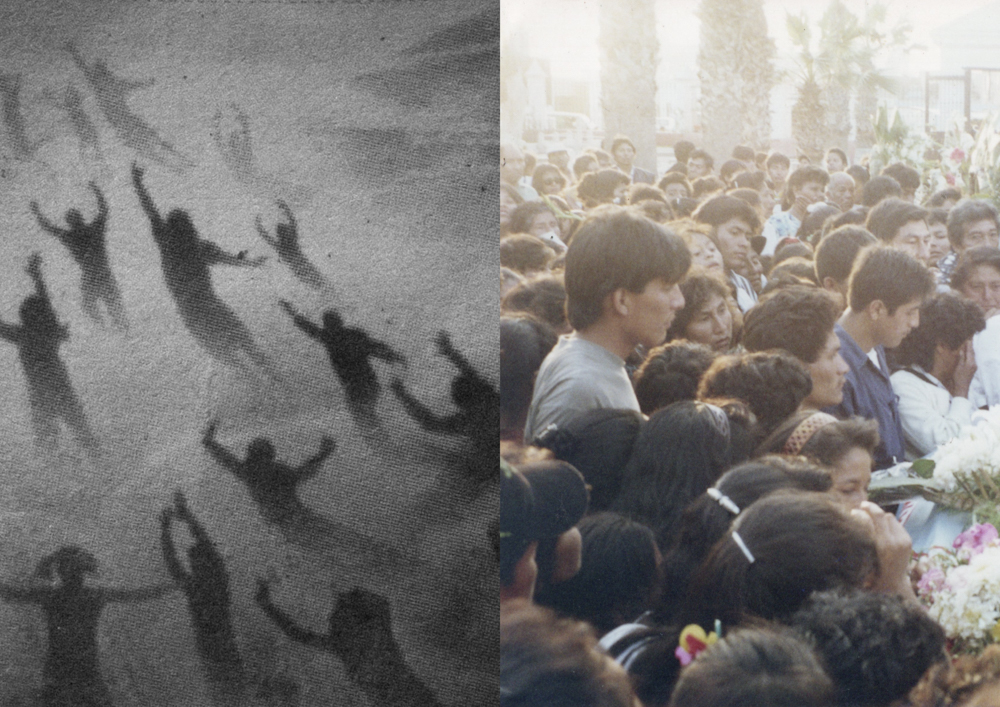

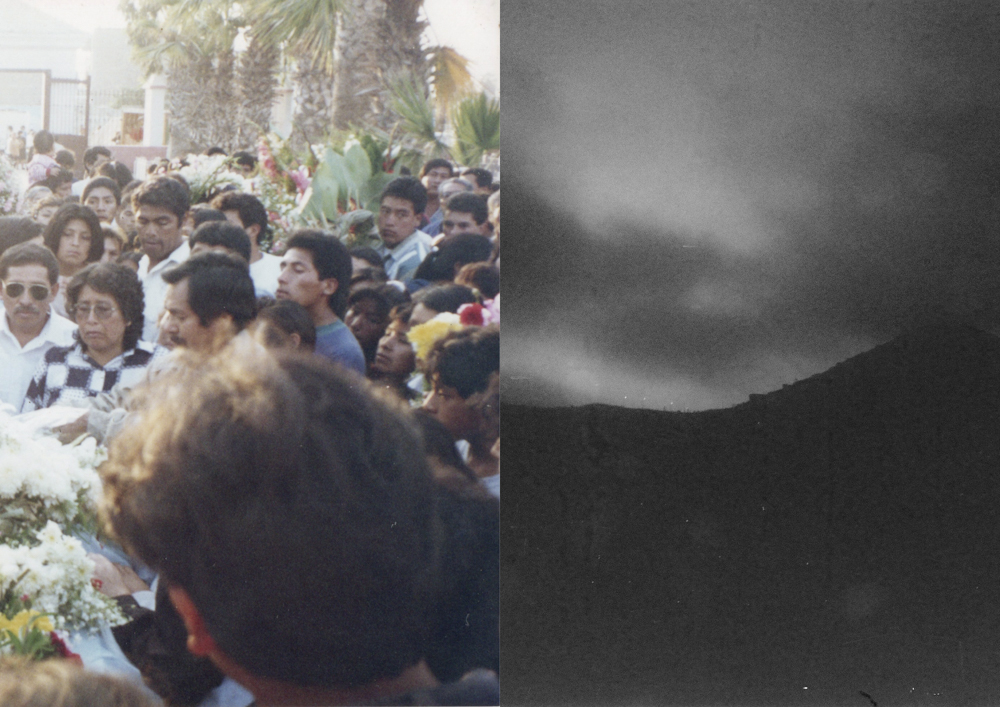

In that sense there is a beginning and an end, which runs through my grandmother’s life. The project, then, is a kind of conversation between the approach that was born from the archive and the one that I did through the documentary approach. Both are easily distinguishable since one is made in black and white and the other in color. In the editorial layout, they are placed alternately, as if narrated simultaneously.

Both aesthetics and discourses developed in parallel but had different origins, in explorations that I did on the topic. Making these two voices, dissimilar but inevitably connected, coexist in the same project was one of the challenges of constructing this work. On the one hand, the color side, made up of archival photographs, own images, and pieces of writing, shed light on the questions that my grandmother faced during her illness regarding faith, death, and family. On the other hand, the black and white images speak of fear, desperation, and faith as an escape from a dark, city reality. This interpretation, a product of my questioning about my grandmother’s decision, is contrasted at different levels with that obtained from her reflections.

I believe that it is precisely in this dialogue that the complexity of the story is found, and what produces a variety of directions and paths of interpretation. My questioning and hurt feelings are shouted from the monochromatic side, while my grandmother’s memories, hopes, and conflicts are whispered on the other side. The narrative of intermittent dynamics between both voices emphasizes this contrast, while each of them gradually approaches the end of the story, each intensifying its own rhythms. The initial support of the photobook was what drew this possibility.

VI: Were there things you chose not to include?

JL:More than things that were chosen not to show, they were editorial decisions. The story was told from a moment in which I could see the situation with a certain perspective, and from there its narrative was built. I definitely chose, from the beginning, not to show my grandmother’s fragility or weakness during her illness. I think I always imagined it as a letter from me to her, with my questions and my thoughts regarding hers, and her decision. It’s my way of telling her how it felt when she left.

That is why what is obtained is an open and evocative narrative that, despite its sometimes documentary nature, is not limited to that language and offers a particular visual imagery.

VI: Part of your work involved revisiting materials from your grandmother’s congregation. I also found the inclusion of images from the media such as TV preachers quite powerful. Could you expand on how the project illuminates how personal faith intersects with communal beliefs and how community/society plays in shaping individual convictions?

JL:The photographic archive of the congregation used is also a family archive, since my family has been an active part of said congregation for as long as I can remember. All the images belong to my family’s history and, therefore, to my grandmother’s.

This project was born as a personal catharsis, as a search for answers from a very intimate and painful event. However, after editing it and seeing it as a discursive proposal, some thematic axes emerged, which currently guide my visual research.

Postmodernity has brought with it a generalized individualization, in which sociality has varied, it has become heterogeneous, vastly plural, of a changing nature.

We live in an eternal mask party. In the way we face public space and life in society, our performativity adapts us to the circumstances. We move within ourselves by living what relates us to different beings.

The Christian faith, when seen as a way of life, is in itself a form of containment and adaptation to the public sphere. The person of faith detaches himself from the masses performatively, resistively, and progressively, generating his own collectivity. Pursue their own ideals. For the person of faith, life is a long race, a good fight.

This long transit is the ultimate goal of the Christian faith. The worldview of faith, deeply linked to the sacred and to death as the last transit towards eternal life, before presenting them as antipodes, suggests death as non-life, stealthily stalking the being alive. The inescapable hope in that eternal place beyond the earthly is the path, the truth, and the life.

This work, in that sense and through Julia’s personal history, offers a visual interpretation of the Christian life understood as a great transition towards eternity, in which the lines that separate the earthly from the heavenly are diluted, at least for faith.

VI: The motifs of hands reaching towards the sky, which I can also see in the picture of the cacti at night, is really evocative. Is there a connection between this gesture?

JL: That detail is an aspect of the work that I noticed during editing. Gestures are very marked in the spaces where faith is professed and in congregations in general. Its most notable manifestation is raising the hands towards the sky. It means a struggle to grasp the heavenly, to get closer to God, and it is seen in many places related to faith. There are songs that invite you to raise your hands while singing them, there are Bible verses that mention it. Hands raised to heaven are an act of adoration, reverence, and faith. My grandmother raised her hands while she sang the day she left. This gesture also evokes, from my point of view, the dilution of the line that separates the earthly from the heavenly, it is a gestural way of expressing faith in that which is beyond.

This motif, and some others, are recurring symbols in the work. They function in the form of communicating vessels, which connect different passages of history and enrich their reading. In the photobook dummy, which is the stage this project is in, this is also evident.

VI: You mention that the second part of the project has a rather “contemporary nuance.” Can you tell us more about this contemporary edge of your project and what current trends in photography inspire you?

JL: I think that this idea of the contemporary is based on the search to get rid of the frameworks of traditional documentary photography, which is what I did before this project. This is evident in the use of files and images of various formats and sources, and also in the aesthetics of the photographs that I took as a documentary. In that sense, this work aligns with the current search that exists in storytelling, which seeks to use diverse formats, both in content and in form.

The use of direct flash is another of the particular characteristics of this work. There are photographers exploring these aesthetics in countries like Thailand and Australia. I like Japanese photographic tradition and current trends, too, and I think they have influenced my work.

In the same way, there is a collective of visual creators from the local underground scene who have always inspired me. Its name is Nada Colectivo.

VI: Stylistically, you are working with diptychs in a very interesting way. What is your approach at pairing images together?

JL: Diptychs were a direct consequence of the photobook format. Thinking about the tactile differences in the paper and the printing method desired for each part, binding decisions were made. If both areas were to be interleaved, they would have to be printed in separate booklets to be sewn later. This meant that, between consecutive booklets, a sheet would appear that would inevitably be a diptych of this type.

From there, the construction of these diptychs was done with more care, responding to the narrative of the story and the criterion of contrast between two voices, which was already being formed. Although it was a consequence of the format, it solidified as an aesthetic proposal.

VI: Looking at your work, I was surprised to find an image that read “I also trust the Lord (he won’t fail me).” Where do you personally stand on these matters of religion and personal choice?

JL: I was raised with the precepts of faith as the foundation of everything else. However, I was always critical of them. This project was born, precisely, from my questions about it, from having seen my grandmother’s decision as absurd at some point. Now, in light of the entire process and after addressing the issue in various ways, including visually, I understand that that decision was an act of love. With my grandma herself, with the family, and with the people who saw her as an example within her congregation. Hence I think that every act of faith is, at some level, an act of love. This is how I understand faith today.

VI: What’s in store for you? Are there any other projects you are working on? How do you envision yourself and this project growing in the years to come?

JL: From this project, especially its documentary side, I identified subcultures, or urban tribes, as one of my main interests. This sociological concept encompasses many of my interests and brings me closer to my quest to convey the complexities that occur within each of the spaces to which I belong or know. In that sense, I continue to explore the Christian faith in my country from the reflections obtained from this project, while I build new thematic universes. For example, since I am very involved in hip-hop culture, especially breaking, I am currently exploring it, from its status as an urban subculture. Being a relatively dissimilar topic, there are new challenges regarding its conceptualization and the visual techniques to be treated. That’s where my research is currently.

Regarding this project, I am very interested in turning it into a photobook, which was its initial premise. I am also very interested in working on it in an expository way so that Julia’s story and her endless love and faith are transmitted, and that it invites other similar stories to be told. It is important to pay attention to the intimate stories that, from their flanks, can connect with their viewers and invite them to get closer, so they can shed light on relevant questions and moving feelings

VI: Last but not least, are there any people you’d like to thank or mention that helped you throughout this process?

JL: This process, more than as a project, has taken place as a cathartic way of dealing with a tragic event. Hence I have to thank each of the members of my closest family. Each one of them, in the time that has passed since my grandmother’s death until now, has made me understand from different perspectives what that decision really meant and the gift it meant.

I want to thank my parents, Dorcas and Julián, to whom I owe everything.

I also want to deeply thank my other four mothers, as I call my mom’s sisters: Jerusa, Raquel, Mical, and Priscila Coca Palomino, for the incomparable role that each one has had in my life and upbringing.

To Andrew and Isaí Coca, Julia’s sons, for the shared feeling on the subject; and to Samuel Coca, my grandfather, for his powerful life story.

And, absolutely, to Julia, for having been the nucleus of the family for many years, for her life of faith and her always unconditional

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Natalie ArruéJuly 28th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Joseph Ladrón de GuevaraJuly 27th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Andrew ZouJuly 26th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Anh NguyenJuly 25th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch 3rd Place Student Prize Winner: Mehrdad MirzaieJuly 24th, 2024