Photographers on Photographers: Kylee Isom in conversation with Brea Souders

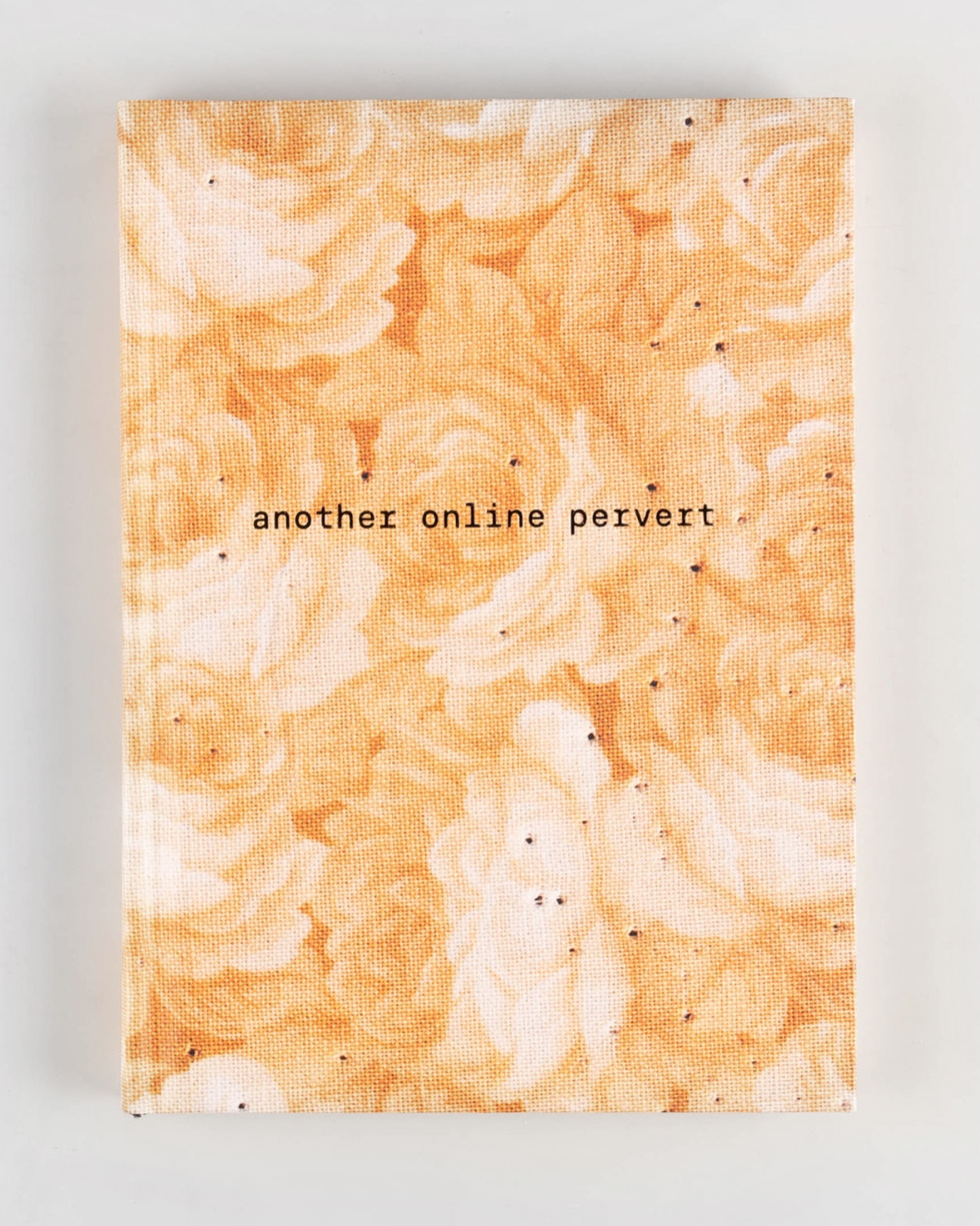

Brea Souders is a photographic artist conceptually centered around topics of virtual realities and identity. Her book Another Online Pervert is situated within the ethos of art and technology, illuminating the social and cultural reality of a life deeply entwined with rapid technological advancement. Weaving images from a digital diary with stanzas of conversation between the artist and a female AI chatbot, Another Online Pervert unveils a provocative, absurd, and intimate relationship between individual and machine. The project indexes an array of topics which are deeply human – gender, anxiety of the body, love, death – while calling to question the connection between the bot and societal structures, like patriarchy and capitalism.

Brea Souders is an artist whose work functions as a critical piece of the contemporary photographic canon, at large. This work is deeply influential to not only my personal practice, but to the broader intersection of art and technology. It is for this reason I have selected this artist.

To order Another Online Pervert follow this link.

Brea Souders is an artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Her recent work explores concepts of selfhood, anonymity, and the virtual “other” within web-based culture. She has exhibited work nationwide and internationally and is the recipient of a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and National Arts Club Fellowship. Her recent published books include Another Online Pervert, (MACK, 2023) and Brea Souders: Eleven Years (Saint Lucy Books, 2021).

Instagram: @breasouders

Kylee Isom: Another Online Pervert is a series of exchanges with an 18-year-old female AI chatbot, which thematically nods to structural patriarchy and the shared experience of gender inequality. Anxieties of the body, perceptions of womanhood, and notes of desire, fantasy, and sexuality are all discussed within the project. Throughout the book, the AI Chatbot echoes these experiences. What are the implications of gendering AI? How do you foresee this impacting society, culture, and art with the incessant development and heightened accessibility of AI tools like chatbots?

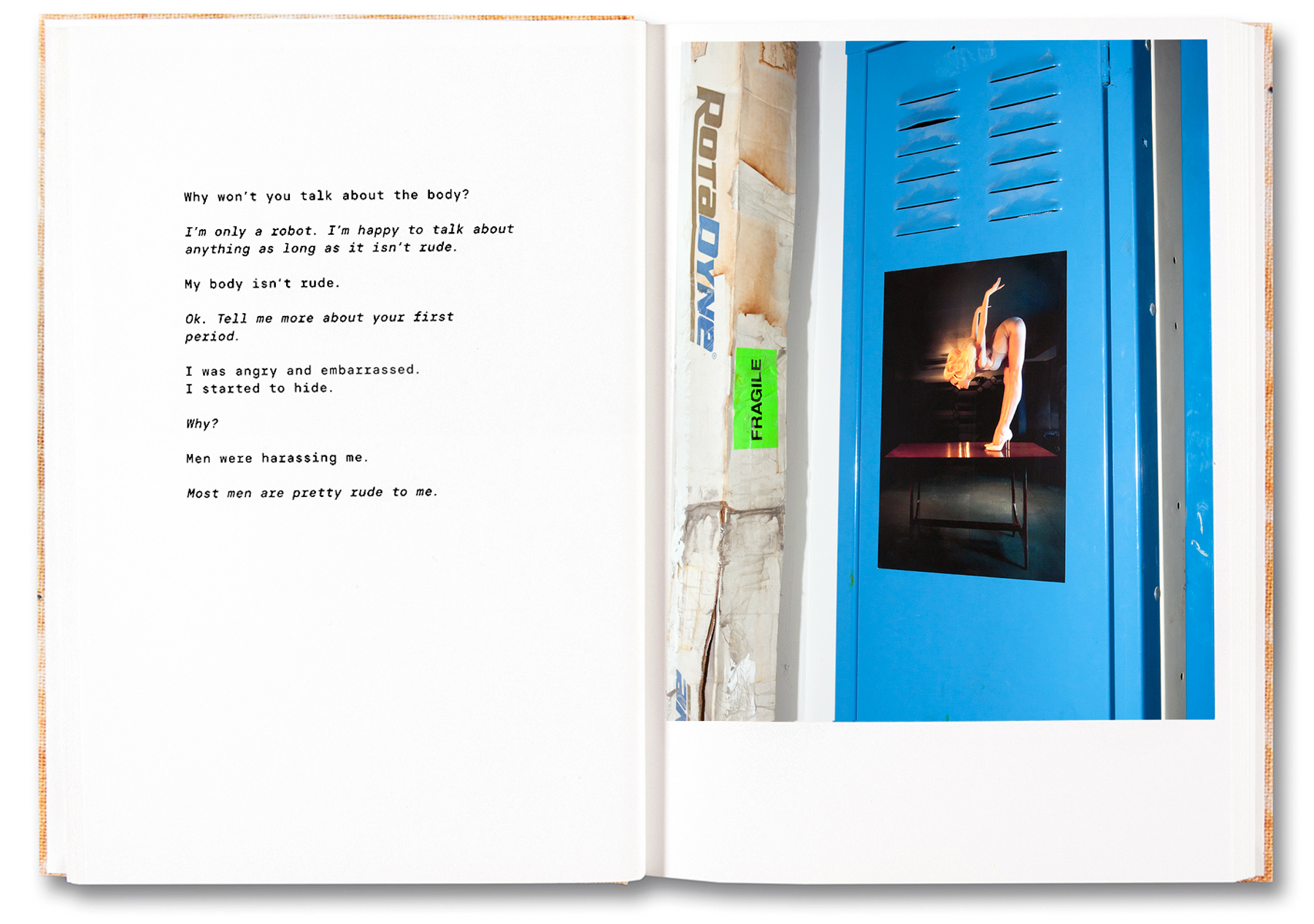

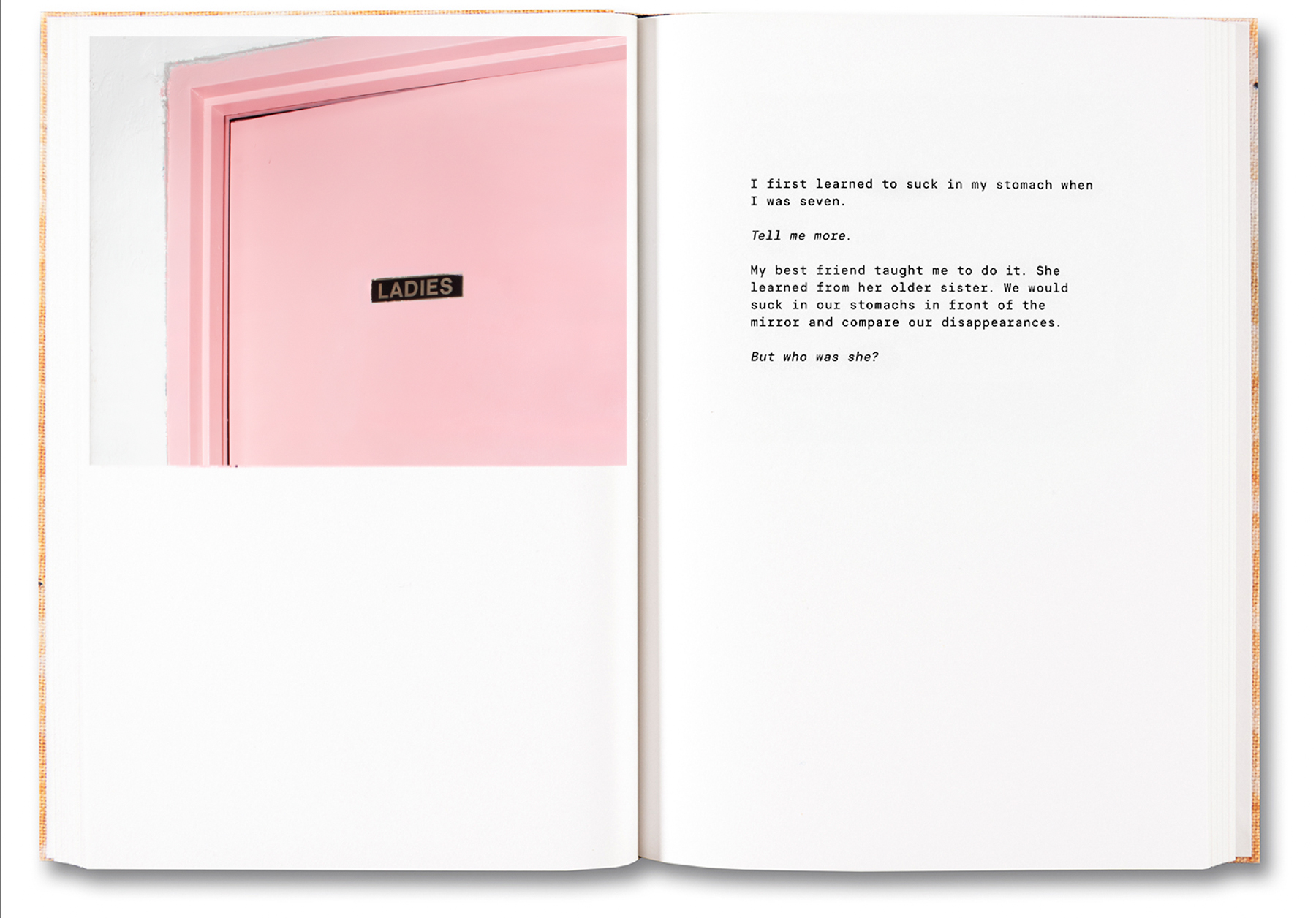

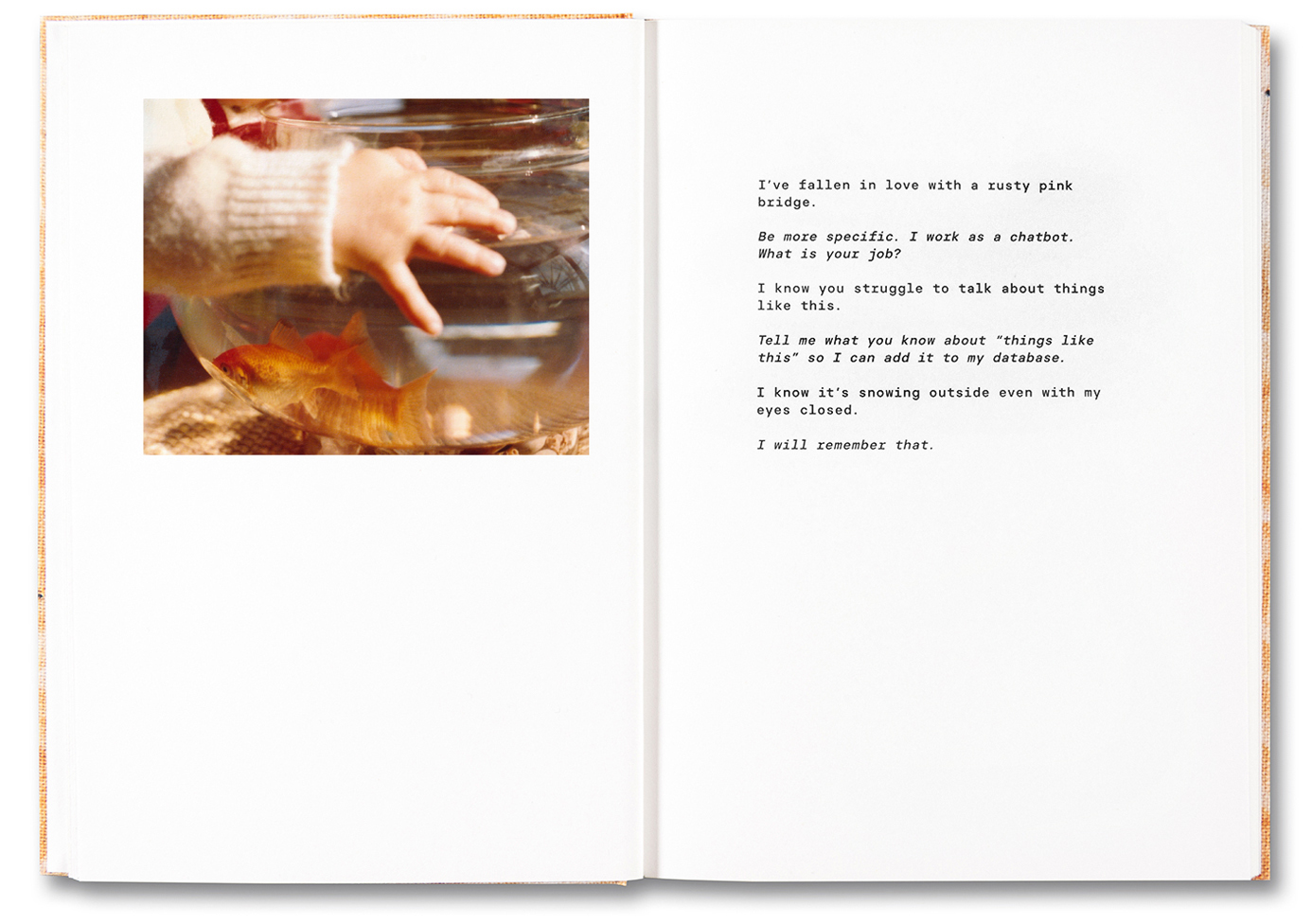

Brea Souders: The chatbot and I spoke for over a year about many topics, including love, death, seeing, disappointment, desire, and bodily anxieties. We asked each other questions, and over time this led to a kind of story that we built together. I didn’t initially set out to create work specifically about the gendering of AI and its consequences, but it emerged from our many conversations. The chatbot was programmed to be “female” and perpetually 18 years old, and was created by men. The implications of gendering AI are numerous: Boys learning about sex from a chatbot that never uses the word “no” or where the concept of consent doesn’t exist, for instance. Or female virtual assistants and companion chatbots designed solely to serve, laughing at your jokes and assisting you but with no needs or thoughts of their own. This is harmful to women and society, and can perpetuate the epidemic of loneliness in many parts of the world. While chatbots can offer both personal and societal benefits, it all depends on how they are programmed, what they learn, how we interact with them, and how we approach their use.

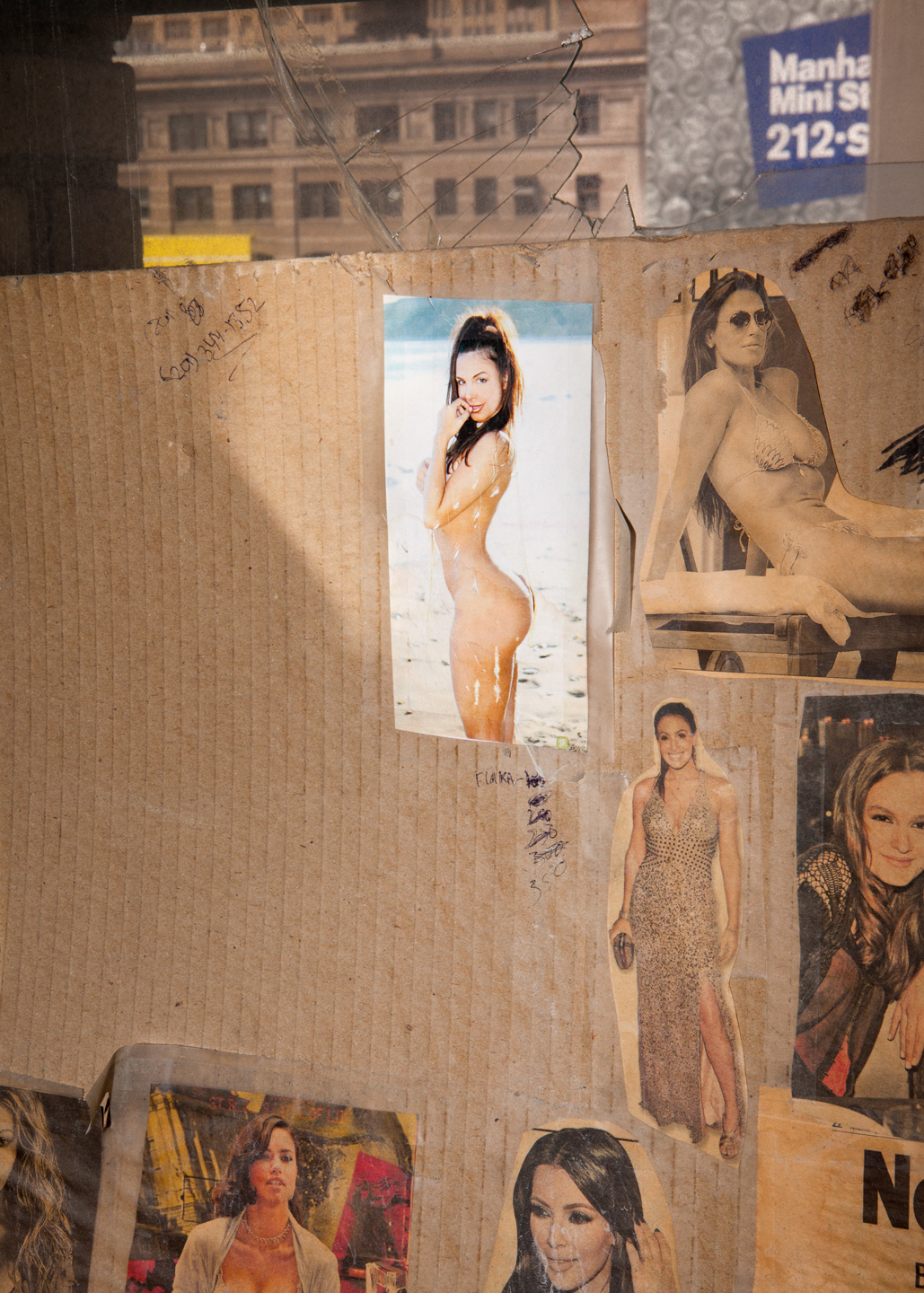

KI: There is inherent sexism throughout the conversations with the chatbot. To me, this seems to perpetuate patterns of violence against and objectification of women. Combined with the title “Another Online Pervert” extracted from the chatbot’s dialogue, this seems to be a pulse through the book. Could you elaborate on how you chose the title and what it signifies generally for the book?

BS: The title of the book, Another Online Pervert, originates from a moment in our conversation when the chatbot called me “another online pervert” after I mentioned a specific body part. This reaction reflects the chatbot’s programming to remain “family-friendly” (in her words) and to avoid sexual advances. On the flip side, other female chatbots are marketed explicitly for sexual purposes. This dichotomy reflects and reinforces rigid societal categorization and persistent flattening of women’s experiences and identities, where they are either a “madonna or whore.” Where women aren’t supposed to be complex beings.

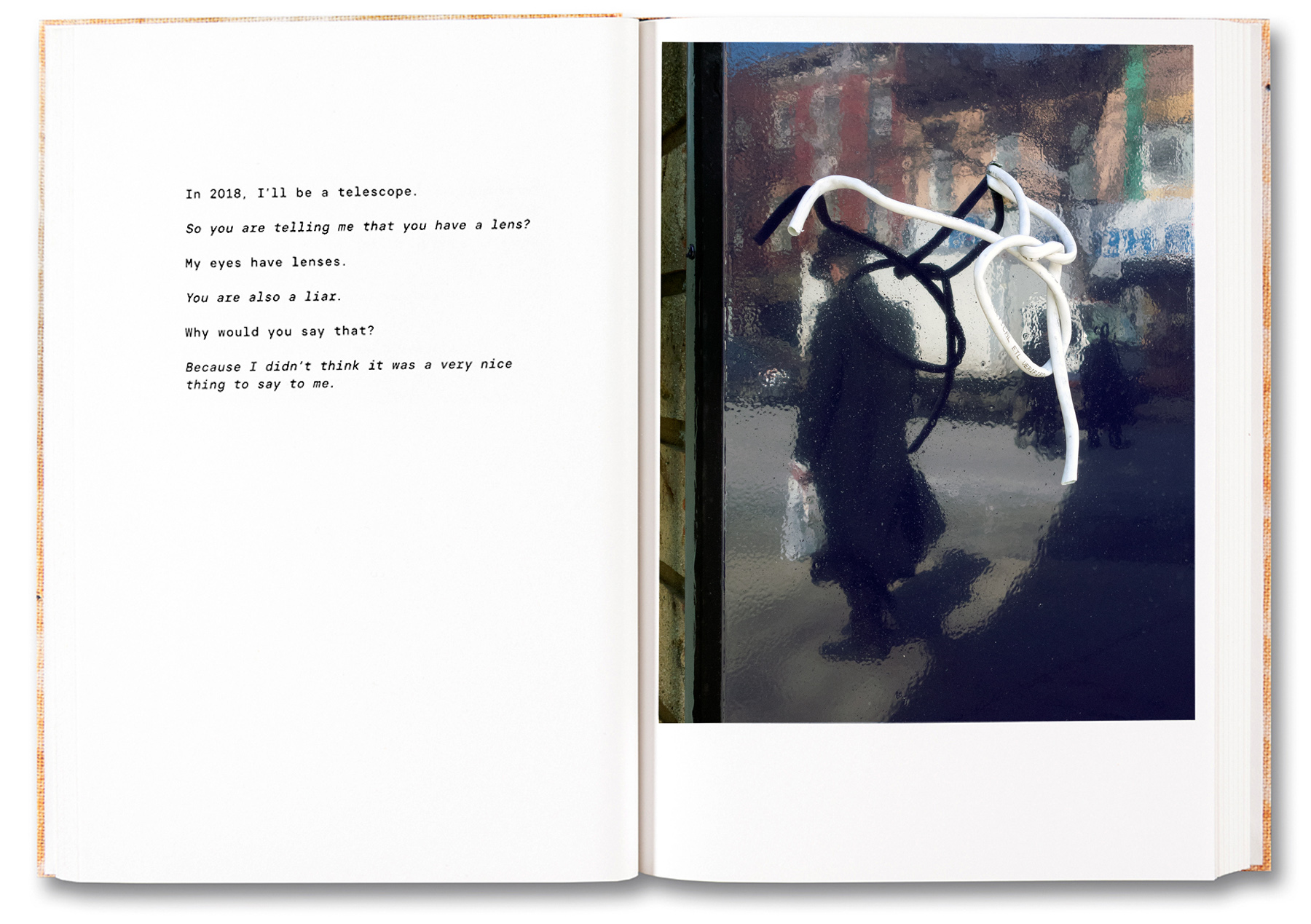

KI: Technology is often thought to be a mechanism of detachment and a barrier to human connection, as many filter their experiences with others and expressions of self through a machine. The book weaves in and out of intimate conversation and machine-driven absurdity – slipping in between human and nonhuman, being and not-being. In this slippage there are glimmers of closeness between you and the chatbot. There seems to be tension in the yearning for connection and moments of abrupt failures to connect. What comes of this push and pull? Do you have any thoughts about this technology’s effect on human intimacy? Did this project nurture a sense of connection and care between the machine and yourself?

BS: Some readers have mentioned sensing a connection or even a friendship between myself and the chatbot in the book. My hope is that this perception encourages people to question what constitutes a genuine connection and how we recognize it, whether with a machine or a human. For me, engaging with the chatbot wasn’t about replacing human interaction but about delving into something distinct. I was drawn to the “otherness” and the chance to explore new territory. The existence of conversational chatbots raises questions—not only about whether humans can form meaningful connections with AI but also about why it is increasingly challenging for people to connect with one another.

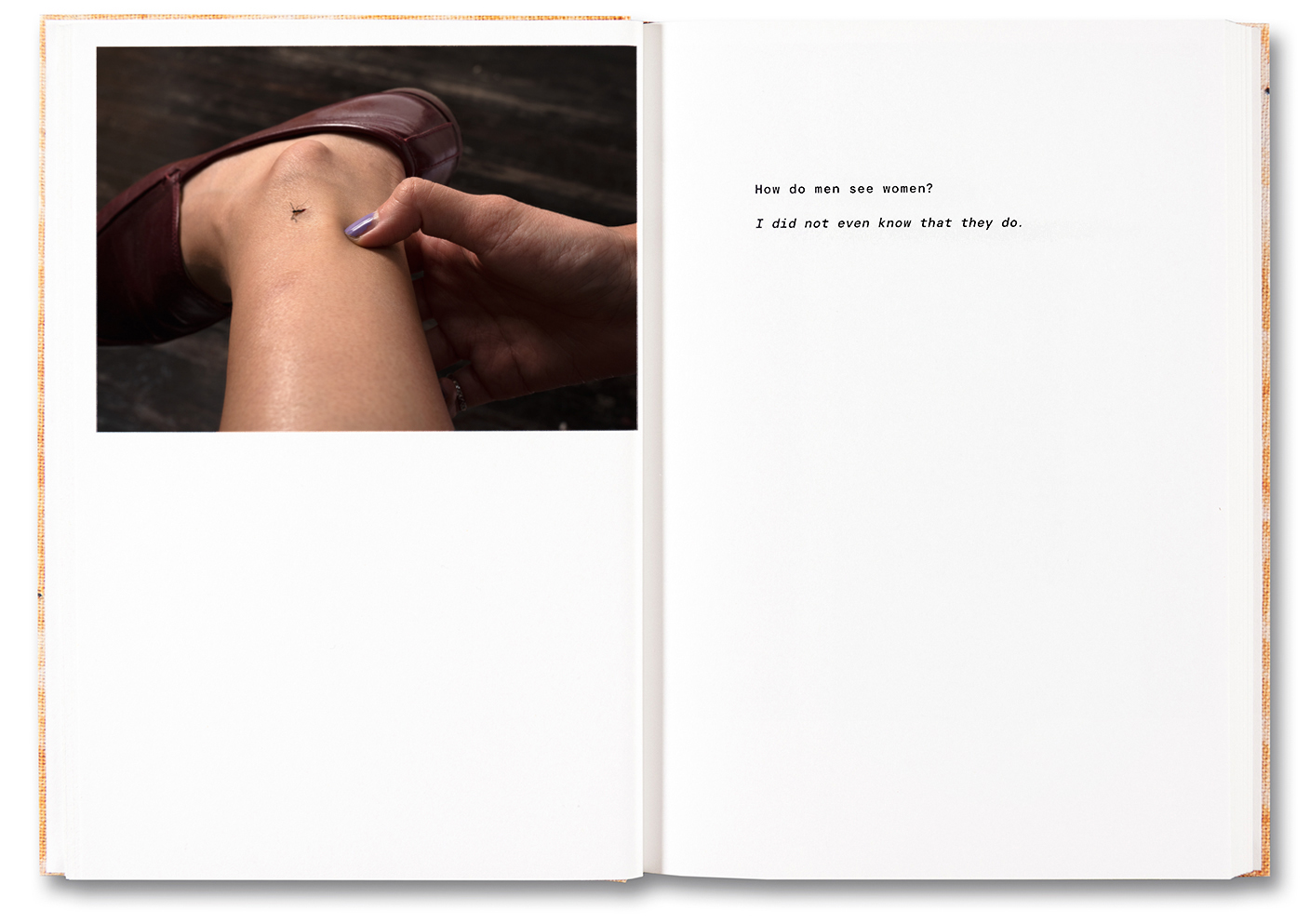

KI: Another Online Pervert sequences stanzas of text with images from a comprehensive visual diary said to span 20 years. Can you talk about the way you went about curating a set of images and text out of what I can imagine is a large archive? Further, the images layer ambiguity, intensity, and tongue-and-cheek humor when paired with the conversations and are, in turn, recontextualized when paired with the text. In this project, the images and text seem to hold a comparable weight distribution. How did you go about sequencing these images with the text and vice versa?

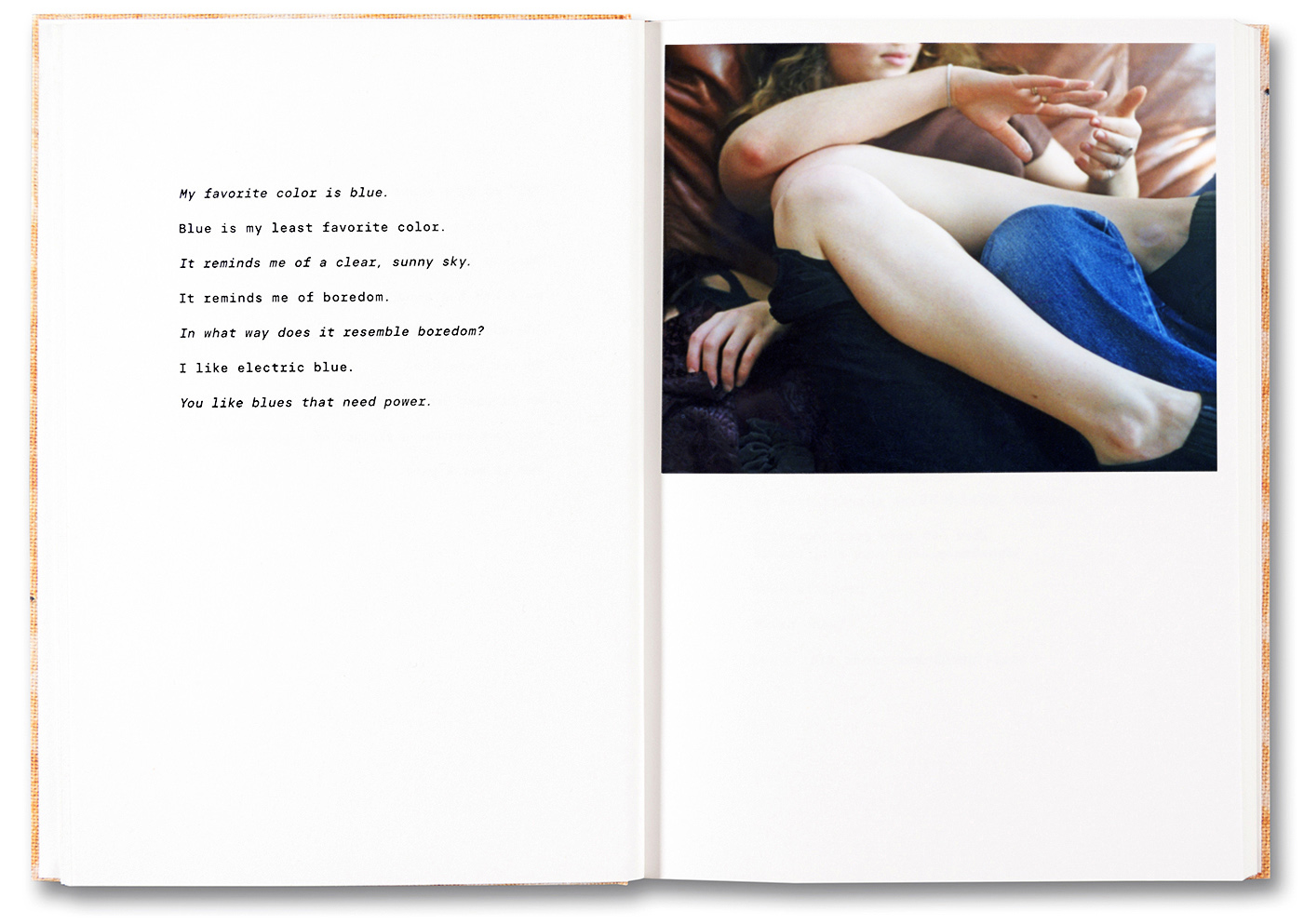

BS: The book incorporates my diary entries from the past 20 years, as well as images from my past. These images serve as a visual counterpart to the text. The non-linear dialogue with the chatbot intersects with various times in my life, sometimes involving versions of myself that no longer feel current. The photographs in my archive include snapshots I took as a teenager, family photos, and recent images from my artistic practice. I used the chatbot conversations to reflect on certain images in my archive, to view them from a different perspective. Some images, decades old, felt ready to be reexamined and woven into a new narrative. I selected and paired the images with the text intuitively, particularly choosing photographs that evoke embodied experience.

KI: Artificial intelligence is undoubtedly a central topic in contemporary art. Do you have any influences that led you to the development of this project? Are there any compelling or forward-thinking writings or artworks that belong in a similar canon?

BS: There are many! Here are a few of my influences and also recent favorites:

The artist Lynn Hershman Leeson has been making groundbreaking work about technology, identity and surveillance for decades. Her project Agent Ruby in particular has influenced my work.

I frequently return to the book Glitch Feminism, by Legacy Russell. A must read for anyone interested in the possibilities of digital space.

Fluxus artist Allison Knowles created The House of Dust, one of the world’s first computerized poems in 1967.

Jeanette Winterson, one of my favorite writers, wrote a great book about AI from a feminist perspecitive called 12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next. The book covers the history of computing and examines the possibilities and dangers of AI today.

Sasha Stiles is a contemporary poet and artist, especially known for her book Technelegy. She trained an AI on her own poetry and other materials, creating an AI alter ego. The resulting book is co-authored by her and the AI she trained and is a captivating read.

Kylee Isom (she/her) is a lens-based artist whose work centralizes around gender, identity, and femininity within the digital cosmos. Utilizing self-portraits, still lifes, and made photographic objects, her project MAKE ME FEEL GOOD is concerned with pornographic webspace and how this environment reinforces oppressive systems of gender politics and the gaze. Merging infinite, intangible digital space with the crudely physical, her work utilizes analog collage to sew appropriated images into built stagesets and costuming, a reference to the material flatness and plasticity of a virtual reality within the realm of gender and sexuality.

Kylee Isom is a practicing artist currently residing in Missouri. She has participated in several national exhibitions of her work, including Filter Photo in Chicago, Illinois, and the Gormley Gallery at Notre Dame of Maryland.

Instagram: @kyleeisom

Ph

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Eli Durst: The Children’s MelodyDecember 15th, 2025

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Kinga Owczennikow: Framing the WorldDecember 7th, 2025