Photography Educator: Melanie Walker

Photography Educator is a new monthly series on Lenscratch. Once a month, we celebrate a dedicated photography teacher by sharing their insights, strategies and excellence in inspiring students of all ages. These educators play a transformative role in student development, acting as mentors and guides who create environments where students feel valued and supported, fostering confidence and resilience. By encouraging exploration and critical thinking, these teachers empower students to pursue their passions and overcome challenges.

It gives me great pleasure to feature Melanie Walker this month. I met Melanie many years ago in Tucson at a Master Class taught by Mary Virginia Swanson. Melanie and I had a nice connection as I had recently lost my mother and Melanie shared her experience of losing her father. I was enthralled with Melanie’s artwork – it was unique and immersive and really pushed at the boundaries of photography.

Melanie, who recently retired after 48 years of teaching, has skillfully blended her artistic life with her career as an educator. Throughout her tenure, she has profoundly influenced countless young artists, inspiring them to pursue their passions with authenticity and a clear vision.

In the words of Melanie’s students,

As a graduate student, I had the pleasure of working with and being mentored by Melanie Walker. She has consistently demonstrated a high level of creativity, technical proficiency, and intellectual curiosity through her work and teaching pedagogy. I have learned a lot of valuable skills from Melanie that I still use to this day and am grateful that I have had the time to watch her work extend around the world as she has retired from teaching at schools, but still finds time to guide me through my journey. She is an absolute gem.

Jasmine Abena Colgan, www.photographsbyjazz.com

Melanie Walker was my professor and MFA committee member at CU Boulder 2018-2021. I am thankful for her support and genuine dedication as an artist and educator. During her classes she allowed me to experiment with animation and encouraged happy mistakes. All her students including me excelled in her courses as she proved to be an outstanding educator. She was always passionate and dedicated to photographic alternative processes and the exploration of the image. Her own artistic work stood out, she was always imaginative, poetic and surreal. In the courses she helped us experiment, contextualize, differentiate, and identify historic content and contemporary art practices.

As a class we were asked to observe and adapt to the various topics and engage in critical thinking. She would always introduce us to new artists that would help us go further in exploring our own creativity. She helped us find ways to incorporate strong themes, playful photographic methods, and add to the conversation of the evolution of photography. Professor Melanie Walker was always inclusive and would let us participate in art shows. She exposed us

to art collections at the library and advocated for our work to be seen in portfolio reviews. She would help us continue to grow and she wanted to see us in contemporary art spaces. She helped us in our critiques with impressive visual analyses through the evaluation of form, content, and context of our work. She demonstrated care and attention as she allowed us to exhibit our work and helped us install the work. Her talent and skills during install helped us understand how to consider the process and the importance of how we present the work. She taught us to use intent behind our creative choices. Her assignments and discussions were always led with kindness and empathy. Melanie Walker as a professor is one of the most valuable and biggest influences in my artistic career. I am following her footsteps and hope to make an impact in my community as well. She was there through the hardest moments in my student life. She grieved with me through the loss of one of the most brilliant and beautiful souls in our student body, Roman Anaya. She is one of the most generous and loving teachers I’ve ever known, I know that there aren’t enough words to express how grateful I am for her.

Alejandra Abad, www.alejandraabad.com

I was very curious about how Melanie maintained such a long profession as an educator while also continuing a prolific and accomplished career as a working artist.

ES: How and why did you get into teaching?

MW: I guess it started early. When I was in elementary school, I came home from school one day and told my parents that I wanted to be a teacher when I grew up. They were delighted and asked me why. The story I was told was that I said that it was because teachers got paid for what they did…my parents laughed and explained to me that my father got paid for making pictures and I was shocked…I thought everyone’s father made pictures.

When I was in high school, my father was teaching photography at Art Center College of Design in LA and I was taking photography classes at Reseda High School with a teacher named Mr. Waren King. My father was supposed to be teaching advertising but instead he was working on getting his students to communicate through their pictures. He would assign Voltaire’s Candide and ask students to convey the notion of ‘the best of all possible worlds’… When students submitted their projects, my father frequently shared the work with me…Meanwhile in my photography classes, I received several awards including Photographer of the Year at my high school…

Around this same time, there was a burgeoning photographic community in LA that my father was a part of. There was a constant stream of photographic artists, many of whom were college professors, coming to the house and it seemed to me that they were having a meaningful life exploring the possibilities of the photographic medium. It was before there was a market for photography and there was nothing to lose in terms of risk taking. I felt like I was surrounded by photographic royalty and it was a huge influence. I wanted to grow up and follow in their footsteps. After I finished grad school, I started teaching two weeks after I received my degree and a month after my 25 th birthday. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but that was 48 years ago, and I just recently left my position at the University of Colorado at Boulder. I feel so fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with so many incredible students at multiple universities. I moved around a lot and probably burned a lot of bridges, but I found myself in places where it didn’t feel right, and I was fortunate enough to be able to move on to other positions. After about 7 different teaching positions, I finally made myself settle in Colorado. Growing up in the west, it felt like a workable place.

ES: Did you have an influential photography mentor or teacher? What was their biggest impact on you?

MW: I was very fortunate to have several mentors, and, of course, the most influential was my father who was also my closest friend. I was mostly influenced by his example. He had a sign up in his studio that read NEVER STOP WORKING. He worked through slumps and discouragement. I remember at one point he was doing some original research in historical processes and was questioned by someone where he got his information which was pretty much dismissed when my father said that he had figured things out for himself. He never had the opportunity to attend college but in high school he excelled in chemistry which allowed him to take historical photography texts and translate the antiquated names of chemicals in formulas into contemporary chemical names which allowed him to explore a wide range of processes. He started working with gum printing and cyanotype in the early 60’s, well before the resurgence of interest in hand made photographs in the late 60’s into the 70’s. He loved books and was constantly reading a wide range of subjects. He taught himself how to run a press and bind books, so I learned about a lot of related processes. He was dedicated to what he called, making funny pictures. All in all, I was incredibly fortunate to grow up in an environment that was so conducive to making art.

ES: What were your challenges in teaching?

MW: I was born legally blind in my left eye and have always been cross eyed so as a result I have always been shy and haven’t had much confidence. That was complicated by having a father who was a beloved professor and well known for his work in the day. I always doubted my accomplishments thinking they were a result of my connection to my father.

Being shy, the first days of class were always awkward compounded by my cross eye. I would point to people to ask their name and the person sitting two seats away would answer. After I realized how cross eyed I was, on the first day I would point out the eye that worked so that things would be more comfortable and productive. It was awkward but I guess it worked…

I also faced challenges being female working in an area that was highly technical. There were job situations where my professionalism was questioned, probably because my teaching style was individual and nurturing. Also in grad school, I was the only female in the program for most of my time in the program. It was around the time of the first wave feminist movement. In reaction to that time, the guys started a group called Male Intelligencia after grad school and supported each other with shows and supporting each other. Needless to say, I wasn’t included in the group so I was always pretty much on my own without much of a supportive community. So many alliances get established in grad school and I didn’t really have that…Also in many of my teaching positions, I was the only female and it was a battle getting heard when making decisions about who to admit into the graduate programs.

ES: What kept you teaching?

MW: I guess I kept teaching because I felt a responsibility to share the challenges and the pleasures of a life in the arts. It’s not an easy path and there is no map. Everyone has to figure things out for themselves, and I tried to set an example for my students. I really enjoyed watching people make their own discoveries and blossom. I was always very pleased when students presented their portfolios at the end of the semester and each person’s work was unique and nothing looked like my work. I really tried to help each student discover their individual approaches to ideas.

ES: What were the different ways that you approached teaching, from traditional classroom style, to mentoring, to facilitating (etc). Did you favor any approach over the others? Did you feel any approach was more beneficial than the others?

MW: My teaching varied quite a bit depending on what the class was that I was teaching. Most of my teaching was conversational and individually focused. I tried to encourage students to think about what was important to them and to make work from that perspective.

When I worked with grad students, their only assignment was to make work, keep a journal and do a presentation connecting their work to what influenced it. With second semester students, again, the focus was to make work constantly and I gave reading assignments on a regular basis. At that level, I found that Art & Fear by Ted Orland & David Bayles was probably the most effective text. I tried to give assignments that would encourage students to explore a range of ideas. Doug Holleley’s books were a great resource as well as The Photographer’s Playbook. I gave a lot of time during class for students to work so I could be there to help refine printing and make the prints sing. My favorite class to teach, which I am proud to say I taught throughout my entire teaching career, was alternative photography. I shared a range of processes and encouraged students to make mistakes because they can be your best teachers. I encouraged the mark of the hand in that class and unique ways of presenting work. It was always fully enrolled in every institution where I had the opportunity to teach. Sometimes it was taught out of a closet, an improvised lab or a proper lab but it was always lively and engaging.

I think a lot of students were not happy with the critique process. That was probably the most challenging part of teaching. I approached critiques in a variety of ways depending on what level class I was working with. Particularly with graduate students, I encouraged them to take responsibility for the feedback they wanted. I would ask them to come to critique with questions about the work they were presenting rather than talking about the work before feedback. I frequently found that if students talked about their work first, the feedback was basically an echo chamber. Sometimes I would ask students to write for 5 minutes about each person’s work and then read back what ideas the work had spawned. Usually, I would encourage the person who was presenting their work to speak last. Frequently the idea of ‘what if you tried this’ would come up in critique so that students were encouraged to fine tune their ideas and keep moving forward. Critiques were always the most difficult part of teaching and I hope that my different approaches were encouraging. I know they can be devastating…

ES: Describe a meaningful anecdote that you had with a student.

MW: Shortly after I started teaching at Boulder, I got a message on my office phone at the university. It was a male voice who didn’t identify himself. It was a long message that went something like this:

“Hello, I was one of your students at SUNY Albany. I wanted to let you know that I have had a meaningful career in photography over the years. I have worked commercially along with making my own personal work. I’ve had exhibitions, received grants, and sold some of my personal work. When I was in your class, you said that I was a “F-up” and would never amount to anything. (I never would have said anything like that…) I have thought about that a lot over the years, and I just wanted to thank you for being the best/worst teacher I have ever had…”

I was very disappointed that there was no way for me to contact this former student and engage in conversation. If he happens to read this article, my words for him: Congratulations! I’m happy that you have had a meaningful life through photography, and please know that I never would have told you that you were a “F-up”. I might have encouraged you to work harder and try different approaches to the same idea so you could develop your vision, but I never would have used those words…

ES: What did you feel was your most important role as a teacher?

MW: I feel like my most important role in teaching was to be supportive, nurturing and to give my students permission. Taking risks was encouraged and in my last years of teaching, I threatened to grade students on the number of failures they made. I tried to offer meaningful feedback and encourage students to understand that in the arts there is no destination but rather a commitment and an ongoing process. Like the adage, to travel is better than to arrive. I also tried to bring a sense of adventure to the historical processes I taught for 48 years, encouraging students to think about what it must have been like to discover a new process and to invent their own personal histories of photography. I also tried to set an example by being immersed in my own work and exhibiting on a regular basis. That was the example that had impacted me at an early age in LA with my father and his productive colleagues who were constantly pushing the envelope.

ES: Has your personal work been affected by your teaching experience? How?

MW: My personal work has been deeply impacted by my teaching in that I always tried to set an example, being active and trying to exhibit my work. I also had to listen to the advice I gave to my students regarding taking risks, experimenting, and working through slumps. In some ways I wish I would have kept a journal of all the ideas I suggested to students about how to push their work further. When I think back, there were a lot of good ideas that fell by the wayside. Another part of teaching that has affected my personal work is that over the years I have saved all the sensitized paper from my alternative processes classes that students have left behind. That is a project that is on the horizon. I plan to use all that beautiful rag paper that was abandoned.

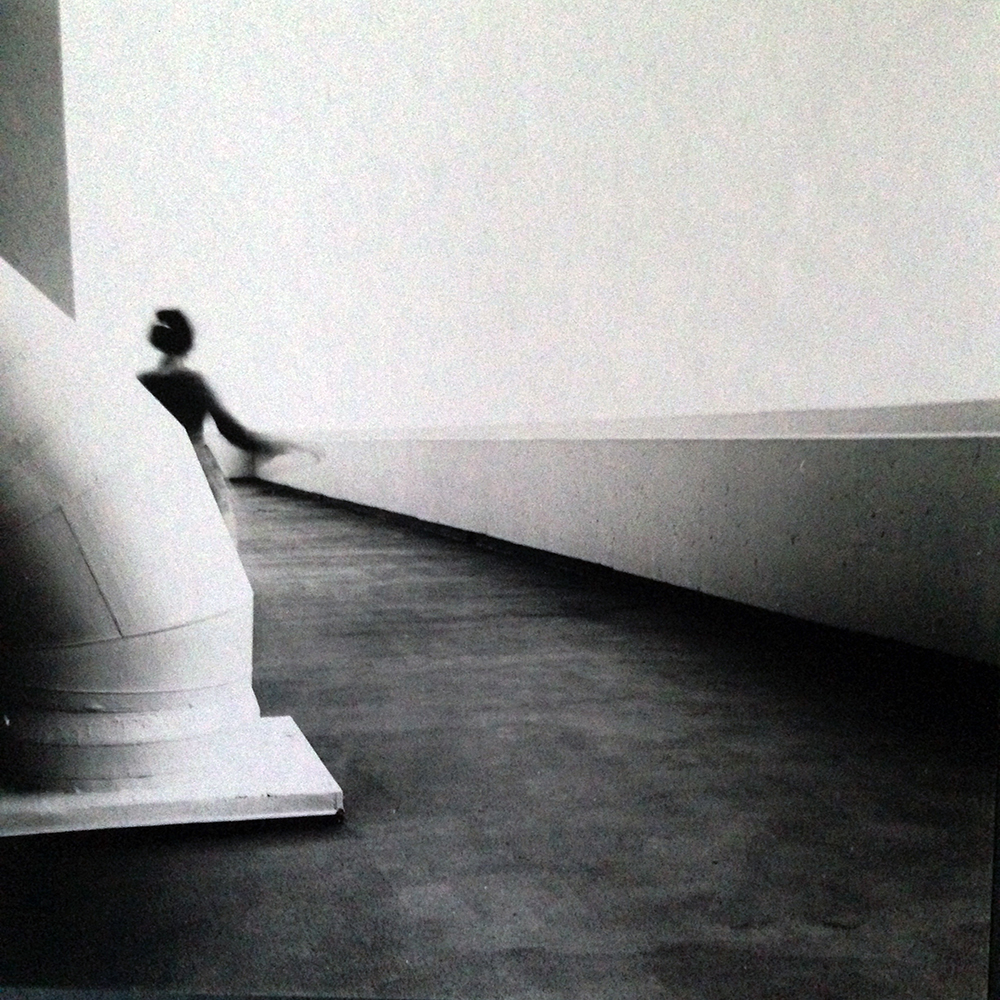

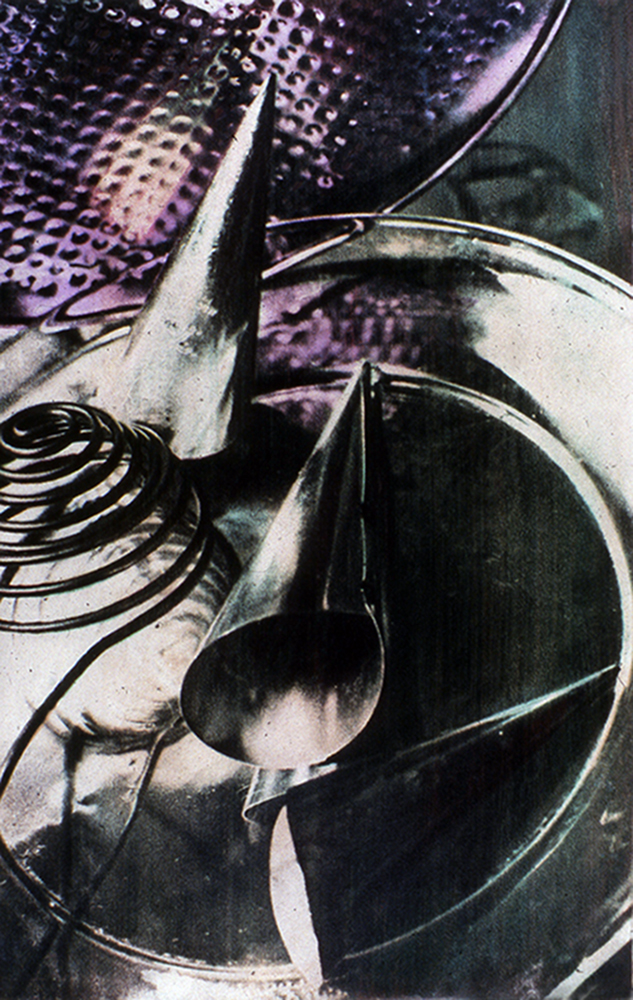

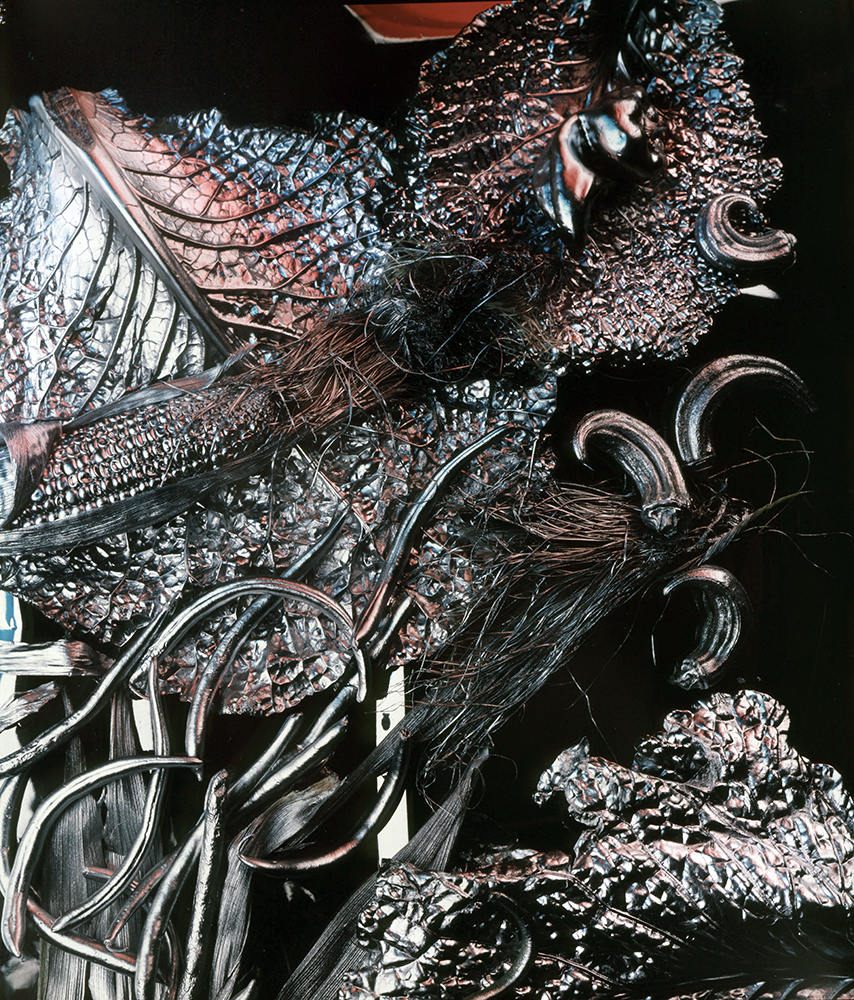

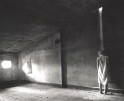

The images featured in this article, spanning over fifty years from graduate school to 2024, vividly depict Melanie’s journey as a unique and significant artist.

Sometimes I think the history of photography is the history of blindness. The moment the shutter opens to record whatever is in front of the lens, it is no longer visible to the person recording that image. I was born legally blind in one eye. I see the world in two ways simultaneously every waking moment with uncorrectable double vision. My work gives voice to my blindness and the questions I have about what is real. As a metaphor for my visual challenges, I work with transparent materials, layering and fabric creating immersive installations as a metaphor for the elusive nature of memory and vision. My practice is haptic and multi-sensory due to my visual challenges. In my photographic practice I have been driven by contemporary sensibilities along with new ways of presentation. Louis Daguerre’s 1822 immersive experiential diorama and a fascination for the pre-history of photography has been at the heart of my work which lies at the intersection of photography, installation, sculpture and textiles. I seek to address our collective longing for connection in these challenging times of division and separation. I live between sight and blindness hoping to serve as a bridge to empathy and compassion.

I seek the intervals. The spaces between us. – Melanie Walker

Most of Melanie’s recent work is designed to be displayed in an environment where the work interacts with the wind. The Sky Clouds imagine a world without borders. This is a work in progress with a goal of creating as many sky flags as there are countries on the planet.

Beneath the Sheltering Sky began during the pandemic when I thought about the air that we all breathe, that has been inhaled by all living things since life began on the planet.

In Memoria was a series of cameraless cyanotype banners made to mirror water. This particular installation was conceived to remember all those lost at sea in search of a better life. Cervia, Italy is on the Adriatic, close to the areas where so many fleeing wars have been lost.

About Melanie

Melanie Walker is a lens-based artist invested in ideas. She has exhibited her work both nationally and internationally and has work in more than 200 permanent collections including the Smithsonian, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson. Her approach to materials includes photographic media, alternative processes, digital art, sculpture, installation, fiber art, printmaking, costume design and public art. As a visually impaired artist, her work is haptic and incorporates transparent and translucent materials to emulate her double vision. She has received numerous grants and fellowships including a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, Colorado Council on the Arts Fellowship, Polaroid Materials Grants and an Aaron

Siskind Award. She is a professor emerita at the University of Colorado at Boulder after teaching for 48 years at various universities throughout the US.

Upcoming Exhibitions:

Nexus at Walker Fine Art, Denver, CO September through November 2024

Red Rocks Community College, January through March 2025

Elizabeth Stone is a Montana-based visual artist exploring potent themes of memory and time deeply rooted within the ambiguity of photography. Stone’s work has been exhibited and is held in collections including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, AZ, Cassilhaus, Chapel Hill, NC, Candela Collection, Richmond, VA, Archive 192, NYC, NY, Nevada Museum of Art Special Collections Library, Reno, NV. Fellowships include Cassilhaus, Ucross Foundation, Jentel Arts, the National Park Service and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts through the Montana Fellowship award from the LEAW Foundation (2019). Recent awards include the Arthur Griffin Award (2024), the inaugural Critical Mass Archive 192 Award (2023) and the Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50 (2022). Process drives Stone’s work as she continues to push and pull at the edge of what defines and how we see the photograph.

Website

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026