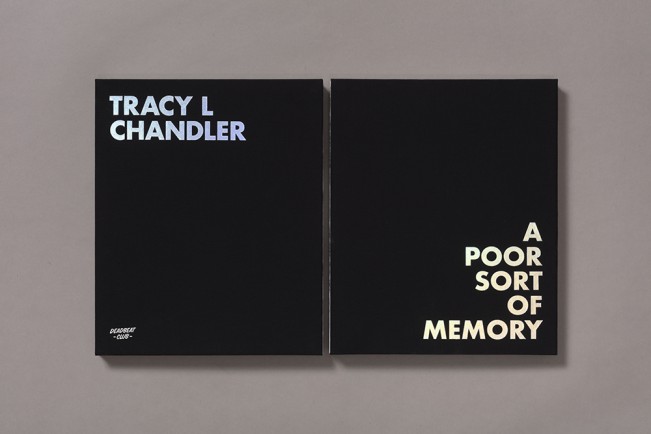

A Poor Sort of Memory by Tracy L Chandler

I recently had the pleasure of meeting Tracy L Chandler in person at ICP Photobook Fest in New York. In advance of that first hello, I did a close read of Tracy’s new book, A Poor Sort of Memory, released in September [2024] by Deadbeat Club, as well as a re-read of Tracy’s archive on Lenscratch of deeply engaged, incredibly thoughtful and perceptive interviews with photographers. I have long admired the way that Tracy engages with folks in the form of the written interview. The conversations never feel rigid or scripted; the reader always learns something about they otherwise would not. I wished for the opportunity to foster that the same kind of dialogue around her work on the occasion of her debut monograph.

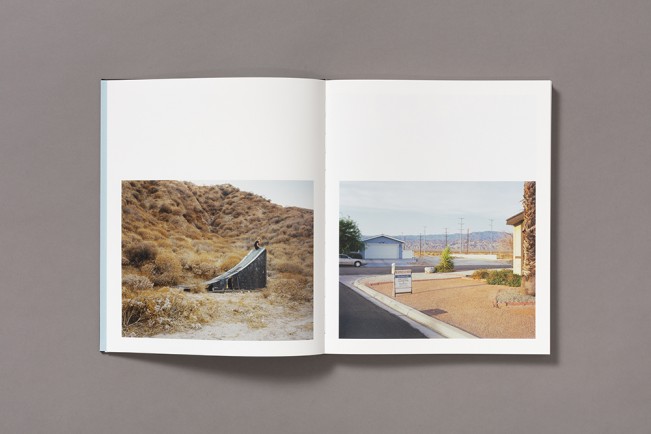

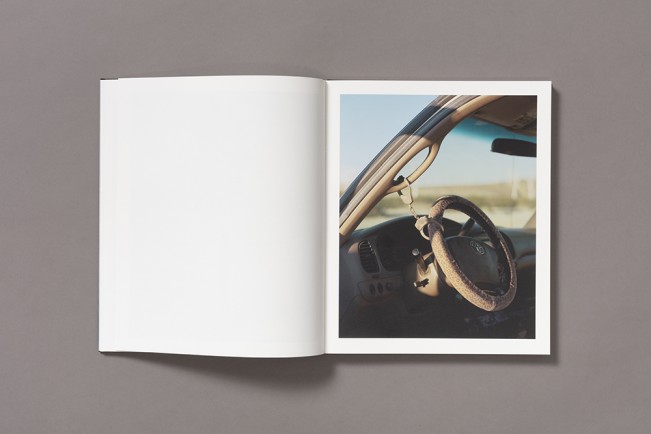

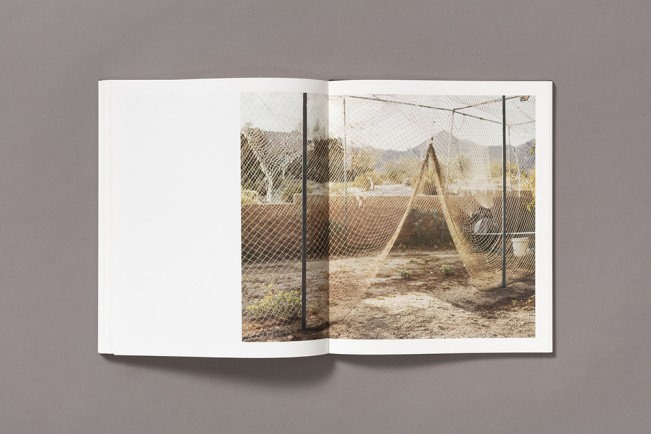

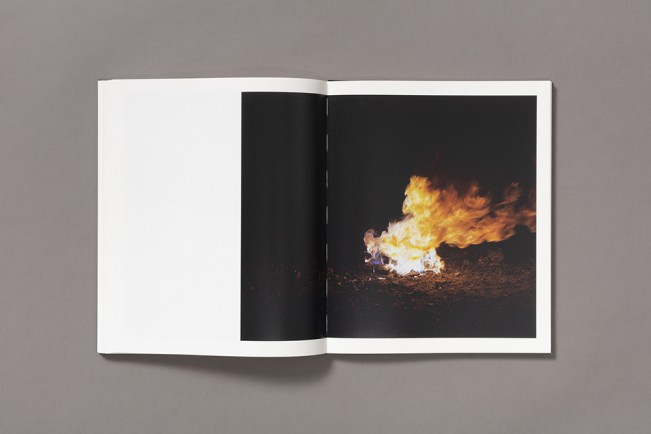

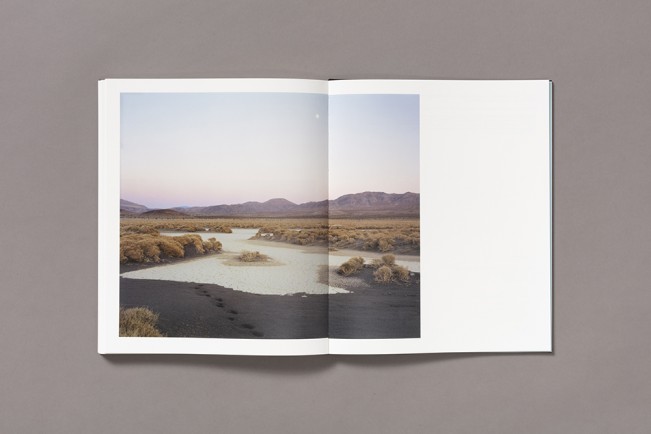

A Poor Sort of Memory transports us to the Coachella Valley of California. Throughout the book’s pages I feel an uneasiness, an ominous force, one that I cannot shake nor easily discern. The pictures feel timeless, all I can trace is the heat of the California sun, only as I imagine it, not as I know it to be due to my own lack of exposure. This book requests one’s contemplation, and in doing so, puts the reader right there in the landscape with the photographer. The book asks that the viewer sit closely, in companionable silence with its narrator, to go in and out of various vortexes in order to find stasis. Buckle in. Yet once it is found, perhaps it is only sensible to go backward in time again, back to the beginning.

The following is a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Sara J. Winston

SJW: To begin, I’m curious if you would tell us about when you first returned to the Coachella Valley, and when this began to feel like a project for you? How old was your son?

TLC: I grew up in Palm Springs and was only really interested in returning to the desert after the birth of my son. I had come of age through a series of family traumas and now, as a parent, I felt a great responsibility to face my own past in order to heal from it and to build an evolved future for my son. In the beginning it felt more compulsive than intentional, I knew I needed to go home but I wasn’t sure why. As I spent time in familiar spaces, memories would return and pieces of my past started to form into a complex understanding of my grief and shame, vulnerability and resilience. My impulse to photograph this process was born out of a need to preserve these memories, good or bad, to pin them down into something I could make sense of and keep forever. Maybe I was afraid that if I forgot my story, I would be more apt to repeat it. The irony is, the harder I tried to do this, the more elusive and flawed the memories seemed. That’s when things moved beyond the personal and got interesting to me as an artist.

SJW: I get the sense the photographs were made over a decade or more, like your journey back to your roots really bends time from what is now and what was before, and moreso, how time might move differently in the desert.

TLC: Yes. In so many ways, time does move differently in the desert. The natural environment is so hardy, almost prehistoric. And any trace of humanity gets sunbaked in a perpetual layer of dust. As I intervene and photograph, I am psychologically projecting my past on to the present. Time layering on time. In making this work, I would revisit sites of specific memories, old skate spots and hideouts, often places where the architecture hasn’t changed and where that feeling of isolation or potential danger seems to be written directly into the landscape, like it was there before me and always will be.

SJW: Living with the complexity of your memories and the complexity of a long term project like this, one that really requires letting the work speak to you after making photographs in a place over many years, is a huge undertaking. What was it like to go through your images to make selections and sequences for the Deadbeat Club edition? How many versions had you made before you began to work with Deadbeat? Was it helpful to work closely with your publisher as a collaborator?

TLC: The work has definitely evolved over time. It initially started with a personal journey of self inquiry in an effort to preserve my past, but the camera revealed the limited subjectivity of both memory and photography. As I revisited sites of specific memory, things would not be quite as I remembered, small details were amiss, and the camera framed more out than in. This left a gap of confusion and doubt that, although initially frustrating, opened things up for possibility. Seeing the futility in the effort of preservation I was free to follow where the work wanted to go. I took a step back from the intention of the photographs and saw the story they wanted to tell on their own. I tried to let go of any literal recreation and use my story, my emotions as the jumping off point for a new photographic fiction. It became less of a documentary and more of a movie based on a true story.

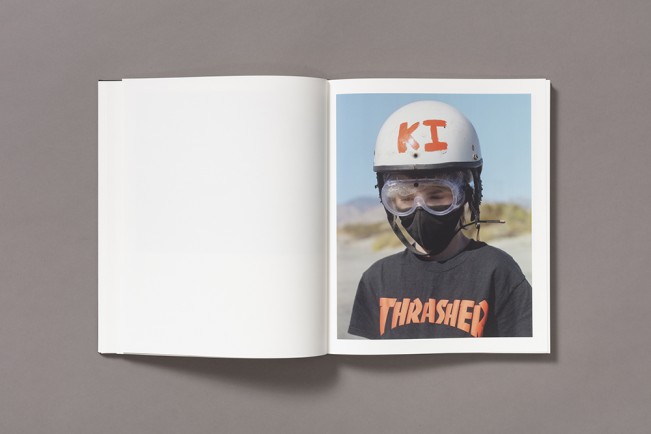

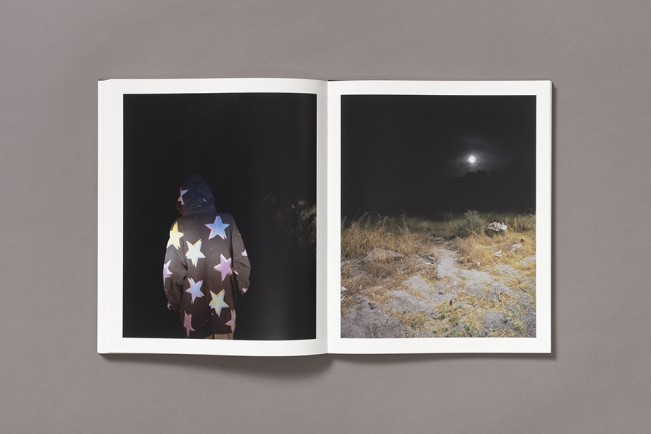

Deadbeat was integral in the editing process. We knew we liked the pictures but I needed their remove in order to help see my blindspots. For example, in previous edits there were many more portraits of my son, Eli. He was a proxy for me, a stand-in protagonist to access this old narrative, but I was also holding on to many of those pictures as a mother looking at a son. We cut many of those portraits from the edit and the new sequence gave the narrative room to breath.

SJW: I love where the sequence, pacing, and design landed in A Poor Sort of Memory. In the book it is challenging to identify the recurring subject is Eli. I think it will take a fastidious viewer to recognize that this is the same person in many of the images rather than a number of different people. It does feel to me like that each person, or each Eli, is a proxy for the narrator. Or for you, if you identify as the narrator here. Do you identify as the narrator?

TLC: I do identify as the narrator, yet this is my story to tell and it is so easy for me to slip into the role of the child protagonist, adrift in this harsh environment, chasing ghosts, evading monsters. There is another character throughout the sequence, an adult man that is often on the periphery. Somehow he is both elusive and intrusive at the same time. I wanted to convey both a sense of longing and danger, such conflicting emotions, especially for a child in relation to a parent.

SJW: Perhaps that’s a funny question to ask, whether you identify as a narrator, but I’m curious about that recreation of an experience that causes you to slip between telling a story and reliving it. You’re both showing and being shown, simultaneously. Was that challenging in the sequencing? Did it require more time, or more consultation with Deadbeat or others?

TLC: I like the way you say that.. “showing and being shown.” There are many layers of tensions there for me, both in privately accessing this past as well as publicly exposing it to the world. I suppose we are always doing that as artists. The sheer act of making something puts our vulnerabilities out there. It is our art, the choices we decided to make, how can that not be personal. Even in work that is not autobiographical we are always “showing and being shown.” It’s terrifying.

For me, the sequencing is a push and pull between intention and listening. I started with laying out the general arc. This narrative is very loose but we do follow a trajectory. We begin with entering the space, then establishing the characters, and weave between emotional states from there. As I was following this road map, the specific pictures would tell me where they wanted to go. It all became more intuitive. I was responding to form, shape and color, as well as vibe. I would just feel it out.

And time plays a big role in sequencing for me. I will often make a sequence and leave it for a while. Then when I come back, there is a new distance and freshness that I can more clearly see what holds true or feels wrong. As for consulting others, that is a mixed-bag. I often keep things close for a long while so that I can work through what the pictures mean for me before I share them in ever widening circles as my confidence and clarity grows. Often the specifics of other’s feedback is less interesting to me than the intention behind it. I can feel when a criticism rings true then I go back and rework the edit or even make new pictures. This cycle can go on over and over again. All of this listening,.. to others, to the pictures, to myself, it all funnels into honing the work down to it’s core essence. But it’s hard to let go in this process. There are many cherished pictures left behind.

SJW: Cherished pictures left behind are one of the trickiest parts of the endeavor of making a book, I think, yet it remains important to kill your darlings. When you thumb through the book and read it now, is there anything about the book object, the sequence, or individual images that surprises you?

TLC: The object for sure….The book is lush, hefty, beautifully printed. Every time I pick it up I am delighted. And also surprised. I never in a million years would have thought this book would have an iridescent rainbow title for the cover. These surprises are born out of great collaboration. I am a long time fan of Deadbeat Club and trusted Clint would do great design. During the production process we set out in one direction but kept running into technical issues in execution. Feeling defeated, we looked at plain foil stamping as a back-up option, the little sample book opened to a page of holographic patterns and iridescent rainbows, we all kind of laughed, like, “yeah, right” and then paused and looked at each other, like, “wait, maybe this could actually be awesome.” The color pattern perfectly matches the post sunset skies of the hazy desert, pastel washes of golden pink to purple and blue. It is subtle but really connects the container to the images inside.

SJW: Would you share some context for the title? How did the work and ultimately the book become A Poor Sort of Memory?

TLC: In Lewis Carrol’s Through the Looking Glass, the white queen says to Alice “It’s a poor sport of memory that only works backwards.” It’s nonsensical, yet profound. It challenges the notion that memory is fixed and only in the past. It posits that memory may work in multiple directions. We are creating memories now and planting them into the future. It’s disorienting, for sure. But I love how it connects to photography. Memory and photography are both similarly flawed in that they are not objective or whole. With subjective framing and only fractions of time, they leave more out than in. And with each act of remembering and photographing, we do not preserve that past but supplant it.

Alice was a big hero of mine as a kid. This resourceful and curious child adventuring alone into unknown lands, challenging the perplexing and oftentimes scary characters she came across. I remember wishing to be brave like her. I reread the series while making this work as a way to reconnect to that younger self. As I went down this “rabbit hole”, I found references to these books everywhere. Alice was my guide.

SJW: It’s almost as if Alice is your collaborator, shepherding you through the trick mirror of considering time and its mistelling of truth, taking you back and forth through the portal between past and present.

Many images in the book steward us on a journey toward doorways, dead-ends, unknown and fantastical abysses. You point us in a direction but don’t give us the satisfaction of taking us all the way to what is on the other side. We have to find our way there on our own, through our own poor sort of memory.

Would you share a little bit about your backstory, your memories, and to what attracts you to the recurring motif of the portal?

TLC: The portal is the promise of a way through. A way through to what exactly, that is up to each viewer. The unknown can be both tantalizing and terrifying. I feel a primal curiosity to face this mystery of life, but there is also cautious ambivalence. I learned early that uncertainty can lead to grave loss. My father was in a critical motorcycle accident when I was young and he remained in a coma for 2 years before finally passing. The loss was (and is still) so great but also a relief from the intolerable uncertainty. This trauma was followed by others, a problematic stepdad, and on it went. I was always looking for a way out,.. through action, distraction, adventure, and fantasy, or even a literal way out, I was always outside of the house. This is one reason most of the pictures are exteriors.

The portals, to me, offer the hope of escape or even transcendence. They drive me forward, seeking, curious. But what is the saying?… “Wherever you go, there you are.” Same goes with making these pictures, no matter which turn I take, I am still within the same story, I am still me. There is no escape. The only thing left is to contend with what is here, now. So that’s where my personal story and these pictures collide. Only by looking back and within, was I able to let go and create something new.

SJW: That context of your life makes me look at the portals a little differently now. Some begin to feel like oracles and spiritual passages, allowing the bending of time even more; looking back and in, changing the past through engagement with it all. It’s all pretty incredible. Thank you for sharing.

TLC: I am so happy to share the work. And thank you for your curiosity and interest. Your questions helped me see the work in new ways. For me, that’s the best thing, to always keep learning and evolving.

Tracy L Chandler is a photographic artist based in Los Angeles, CA. Her work explores humanity and her own personal story reflected through portraiture, landscape, and narrative. Her photographs address themes of time, place, memory, seeing, and being seen.

In 2023, she had a solo exhibition at Gallery 169 in Santa Monica as well as screened a short film of her project A Poor Sort of Memory at the Arles Rencontres photography festival in France. Tracy has participated in multiple group exhibitions including The Oregon Contemporary, The Museum of Warsaw, Baxter St Gallery, These Days Gallery, Candela Gallery, and The Humid. Her work has garnered many recognitions including scholarships and awards from the Hopper Prize Foundation, Lucie Foundation, CriticalMass, PH Museum, Arles Book Awards, Charcoal Book Club, Urbanautica Institute, and Los Angeles Center of Photography. Her work have been featured in publications including Fotofilmic, California Sun, and the Humble Arts Foundation

Deadbeat Club is an independent publishing group & coffee roaster located in Los Angeles, California. Rooted in contemporary photography, our ethos on small run, limited edition publications carries into our small batch single origin, signature blend and limited release coffees.

Each Deadbeat Club project is selected with the expectation of collaboration and a longstanding partnership. Working closely with photographers and artists around the world, making sure their original vision is never compromised, we produce a body of work that we are proud to share with our community.

Sara J. Winston is an artist and contributor to Lenscratch.

Follow Tracy L Chandler, Deadbeat CLub, and Sara J. Winston on Instagram:

@tracylchandler; @deadbeatclub; @sarajwinston

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026