The Inhabitants by Raymond Meeks and George Weld

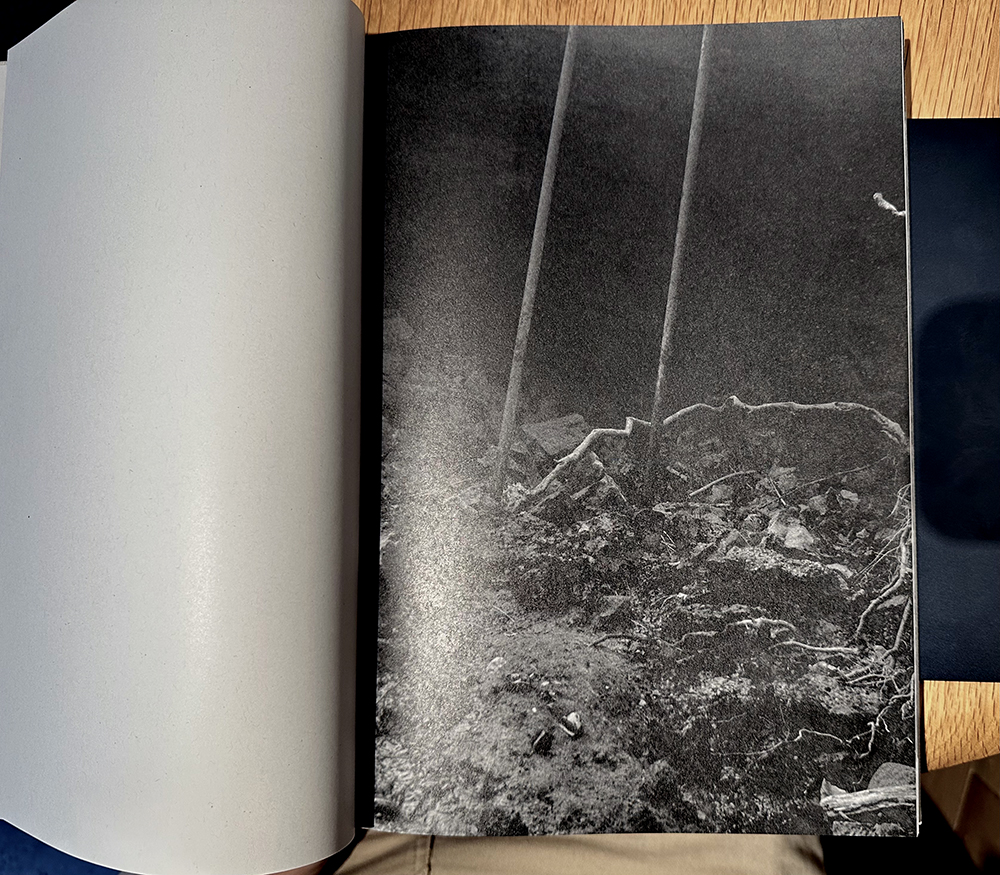

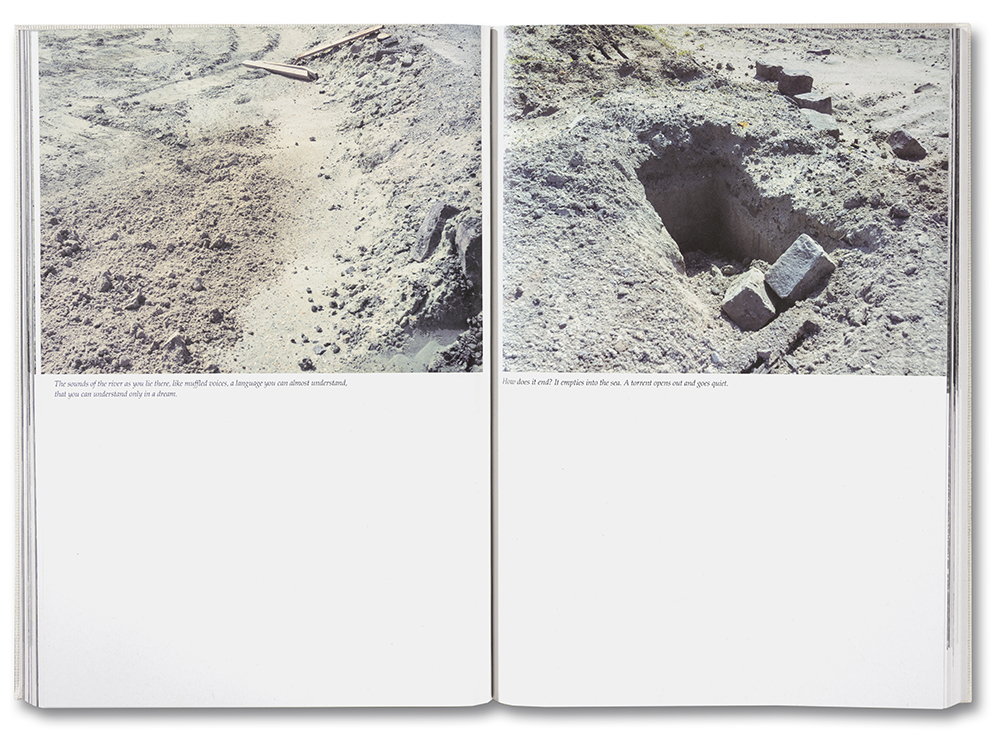

“A word on a slate, written in chalk, chalk wiped clean with a rag. A slate on a wall, hung by a wire.”And then a black space fronted by silvered rubble, detritus, dirt; two poles rising into the gray light; a tree limb zigzags its way into the frame like a petrified electric current settling between the poles; jagged stones, pockmarked rocks, twigs, sticks, trash, and dust. I feel a slippage. This space oscillates between the terrene and the alien. It is like the bottom of the ocean, foreign and mysterious yet nonetheless a site of familiarity. We know this place of the unknown.

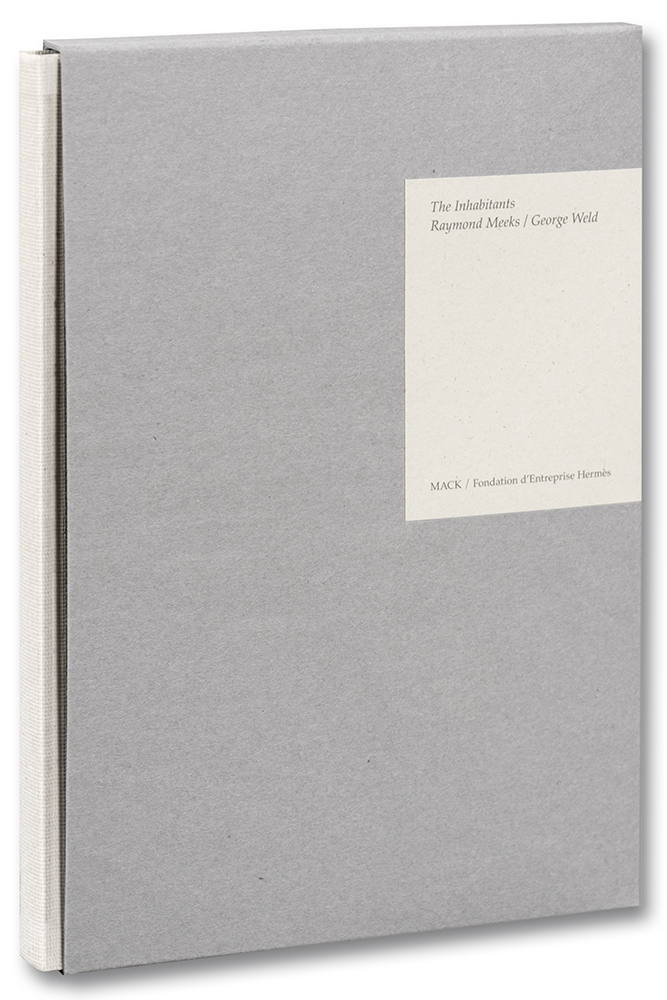

So begins the collaborative effort The Inhabitants by photographer Raymond Meeks and poet/photographer George Weld, released by MACK Books in the Fall of 2023 and co-published with Fondation d’entreprise Hermès. The works were made over the summer of 2022 in Northern France while Meeks was engaged as the sixth Immersion laureate, a French–American Photographic Commission established by the Fondation d’entreprise Hermè. The Immersion—an annual program—consists of alternating residencies between France and the United States aimed at the creation of original photographic work that stresses “the geographical and cultural territory they explore during their residencies.”

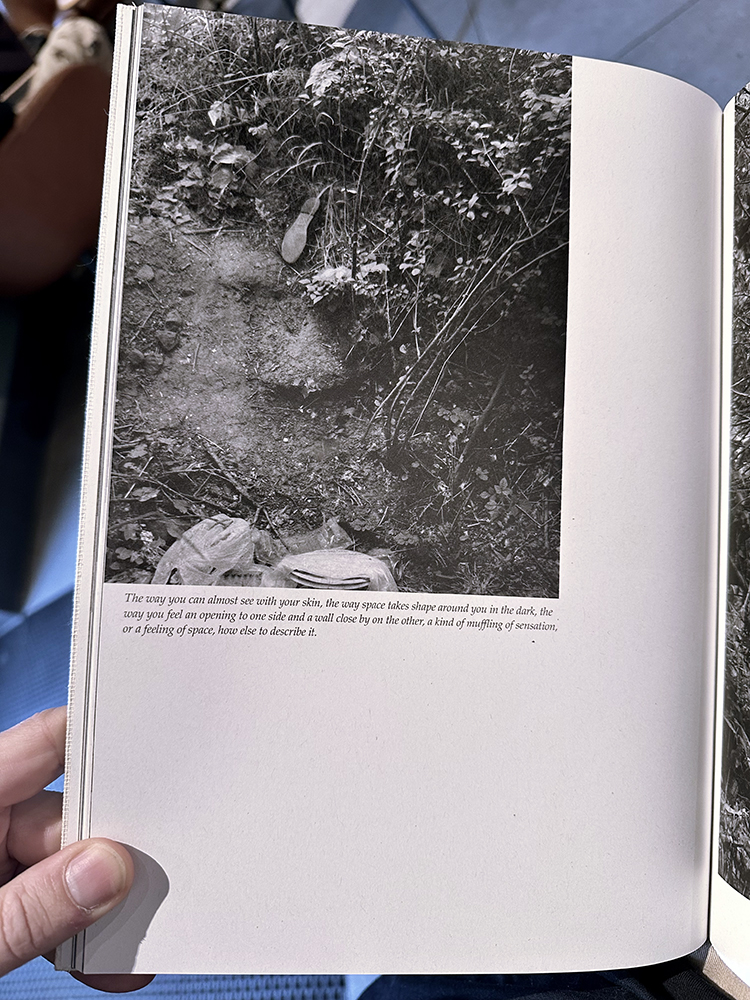

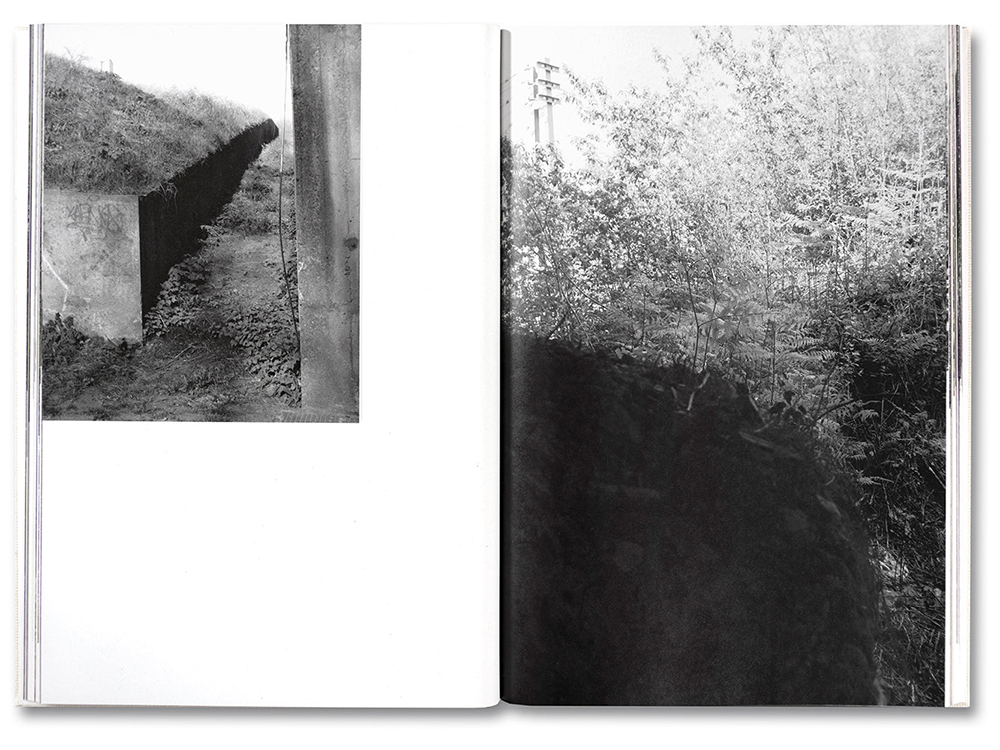

Meeks has long forged the banal with the mysterious, creating photographs that exist in the space between the evidential, the vernacular, and the ephemeral. The terrain of northern France here replaces the familiar mid-western and north-eastern look that we have come to know through Meeks. Consisting almost entirely of black and white photographs paired with Weld’s expansive yet concise writing, this book is a trek through the empty spaces of this land, spaces that are nonetheless inhabited by abandoned tires, string tangled around branches (or has it been purposefully tied?), temporary fire spots, tossed blankets, and other detritus—presence through absence. In one photograph, an upturned dress shoe lies in grass at the edge of a heavily brushed area and marks the top of a well-trod dirt ground. It is not quite a path but is trafficked enough to keep the growth at bay. At the bottom of the image, clipped by the frame, are what appear to be plates and other items covered in plastic. Is this a living space? A crime scene?

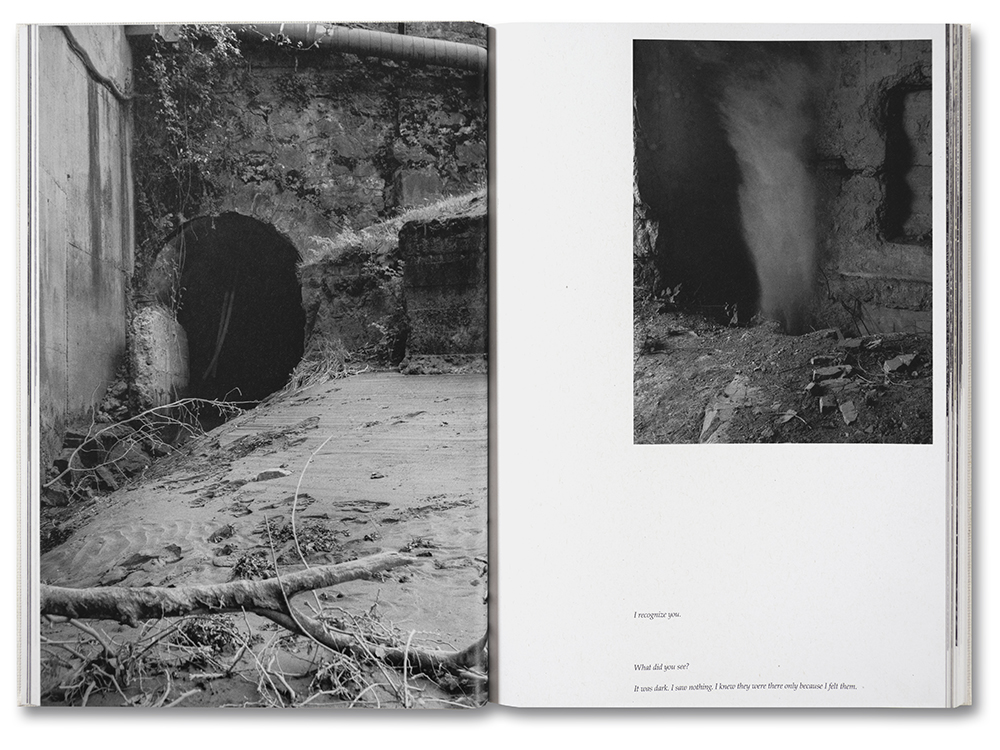

What is exceptional about Meeks’s work is that it always treads between specificity and total ambiguity. What can we glean from this work that attests to North France specifically? Perhaps the decaying bricked arches, overwhelmed with vegetation and voided by their black mass tunnels, are remnants of Roman aqueducts? Or are they just forgotten local architecture in the process of disappearing? Any historical, environmental, or cultural context is buried in the forms represented here or otherwise locked away behind the surface of the image. And yet there are clues to the human presence throughout: graffiti, trash, fences, a bridge, and buildings (out of focus), among other things.

George Weld’s words are tucked beneath photographs, at the edge of the blank pages, or near the gutter. It can be easy to miss these if one isn’t fully engaged. The lines bounce between description, first-person narrative, and fleeting dialogue (“I recognize you.” / “What did you see?” / “It was dark. I saw nothing. I knew they were there only because I felt them.”). Although at times, one may read his words as responses to the photographs (“Phrases of music, passages of speech: words that seem to become patterns, repeating rhythms or associations. A motif. An aria. An erratic, unexpected protrusion”), they create spaces of their own that evoke micro-narratives; the sound of a fork in a tin can, laughter in the weeds, the buzz of a phone. Narrators adds a presence to the images (or perhaps it is Meek’s photographs that lend space to the voice of the text): “I prayed into the bowl of my hands, and my words pooled there like something to pour over a sunburned neck, to darken a patch of bone-dry soil, to stiffen the stalk of a drooping leaf, to wet a parched tongue and free it to speak.”

Some of the photographs push into more formal territory, likening to certain photographs by Harry Callahan or Ellsworth Kelly that use light, shadow, and the structures of the world to create geometric abstraction out of recognizable terrain and elements. For example, the shadowed side of a wall becomes a thick black band thinning as it recedes into space à la Franz Kline, while a brutalist concrete mass—

chipped, cracked, stained—fills the right side of the frame. And there are areas where I think images could have been cut, images that seem to reduce this sense of fleeting habitation throughout. The photographs depicting the roadside with its metal-beam barriers and road signs or the industrial park bounded by concrete barriers feel superfluous and common in a way that seems out of place among the images that make up these pages.

There are color photographs here, too—a wonderful surprise. They are not the saturated colors of an Eggleston or Shore but rather the pastel-tint of hand-colored prints or the faded quality of old tri-color gum bichromates. They’re yellowish and greenish with tints of blue but monochromatic like faded polaroids. These photographs feel archeological and remind me of the 19th-century travelogue photographs by Gustave Le Gray. In fact, Le Gray’s photographs of the forest of Fontainebleau—a site in north-central France—are echoed among some of Meeks’s photographs presented here (or it is hard for me to see otherwise).

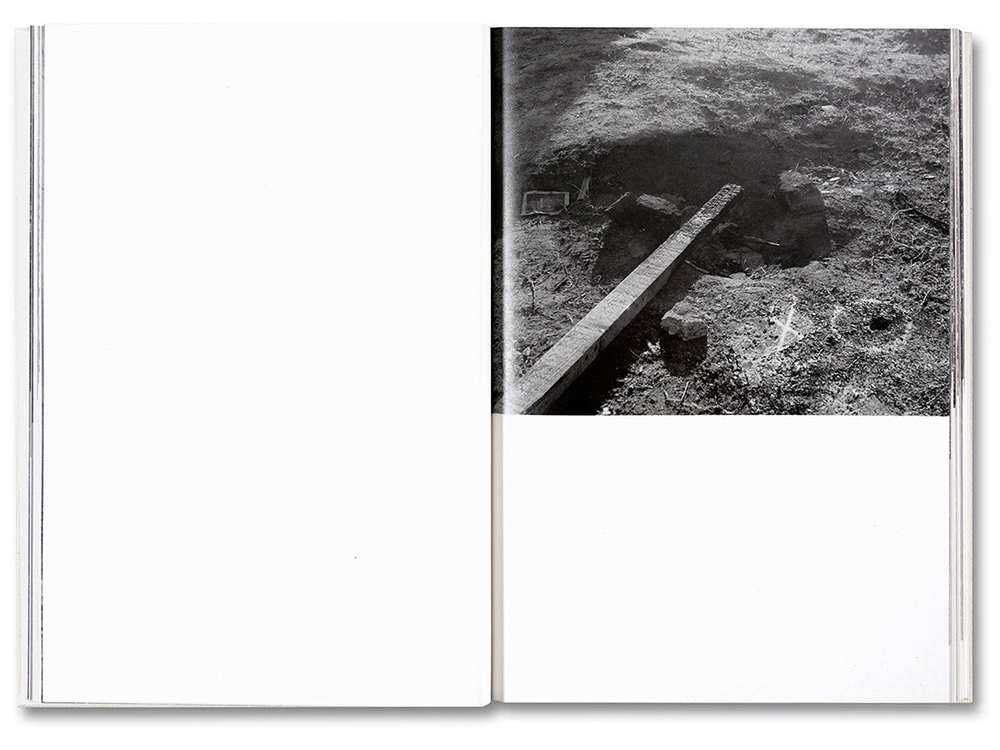

And then back to black and white. A wooden pole lays in dirt and stone. Its charred end extends over a roughly dug hole—the site of an impromptu fire pit. A prominent X and O, painted in white on the graveled floor, demands attention at the bottom right of the frame. With love. This is the locus of the image. There is a black hole in the white O that I cannot stop staring at. Perhaps this is because Meeks’s photographs feel like fleeting intermezzos within his own internal world—and we are privy to their materialization. Weld’s words bouy this sense above a kind of fogginess, elusive but nonetheless present. Together, they are attempting to draw them out into the light, to materialize them. As Weld writes, “First water, then land. First darkness, then light. Breath into human form, breath into voice, breath into song. Void into form. Place out of no-place.” And later he writes, “I need to be seen to know I am real.”

his book is a true collaboration, where—despite Meeks’s clear style—the two artists meld their respective mediums into one voice that eclipses each individually, a true synthesis. This voice takes control and drives the body to an exceptional place. The blank spaces—of the book itself and those created between image and text—become hinges that hold them together. It’s hard to imagine them as separate; they are tied, inexplicably, like the string on the trees, both ultimately singular yet together. Early in the book, Weld writes that “the hunger for meaning deforms everything.” The Inhabitants, although made out of the specificity of time and place, beckon us to consider a much larger theme, which is the human condition as the states of all things, all matter and non-matter, shift and change, and we take note only in a state of in-between, our persistent and futile attempt to concretize it all and in doing so, perhaps, as Weld suggests, deform everything. So, who are the inhabitants? Are they vagabonds, runaways, escapists, transients, the unhoused? Or are they us, the reader and active looker?

“We remembered the story by making it a song,” writes Weld, a song about us, the inhabitants.

The Inhabitants

Raymond Meeks / George Weld

Embossed hardcover with slipcase (Special Edition available)

21.5 x 30cm, 172 pages

€45 £45 $55

September 2023

Colin Edgington is a visual artist and writer who explores notions of accumulation, memory, fiction, politics of labor, exploitation, and the environment. His visual work has been exhibited internationally—winning the Iowa Review Photography Prize in 2012 for his photographic novel—and his writings published widely.

He holds an MFA in Art Criticism and Writing from the School of Visual Arts, NYC (2016), an MFA in studio art from the Mason Gross School of Arts, Rutgers University (2010), and a BAFA in studio art from the University of New Mexico (2005).

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025