The 2025 Lenscratch 2nd Place Student Prize Winner: Christian Lee

It is with pleasure that the jurors announce the 2025 Lenscratch Student Prize 2nd Place Winner, Christian Lee. Lee was selected for his project, The Warmth of Other Suns, and is currently pursuing a BA at The School of the Arts and Architecture at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). The 2nd Place Winner receives a $750 Cash Award, a feature on Lenscratch, a mini exhibition on the Curated Fridge, and a Lenscratch T-shirt and Tote.

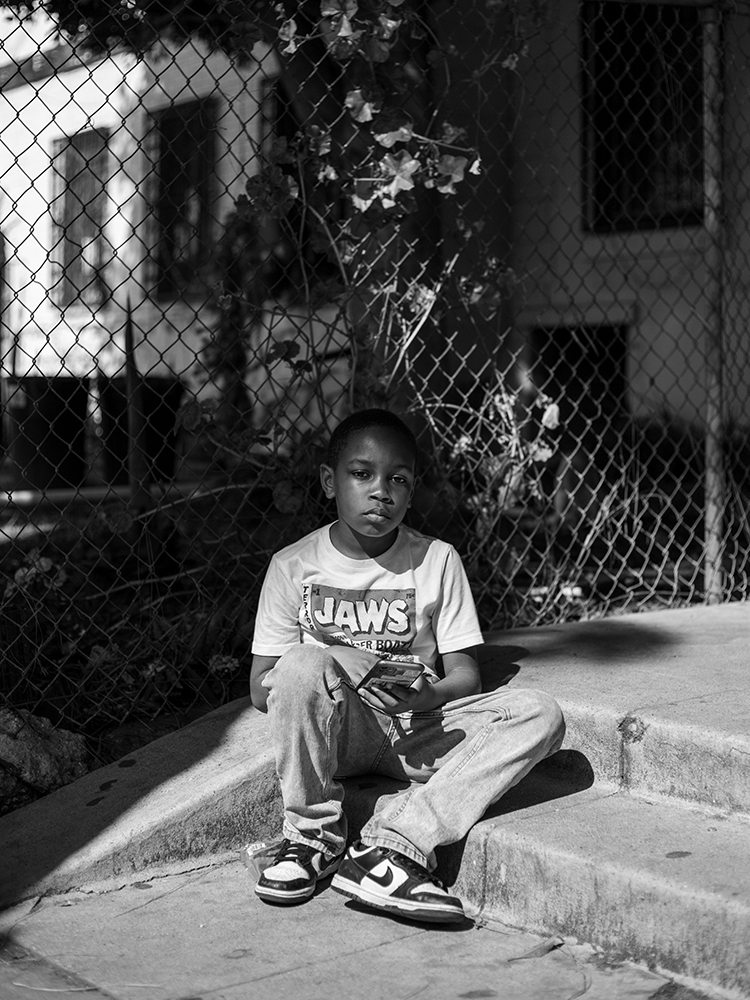

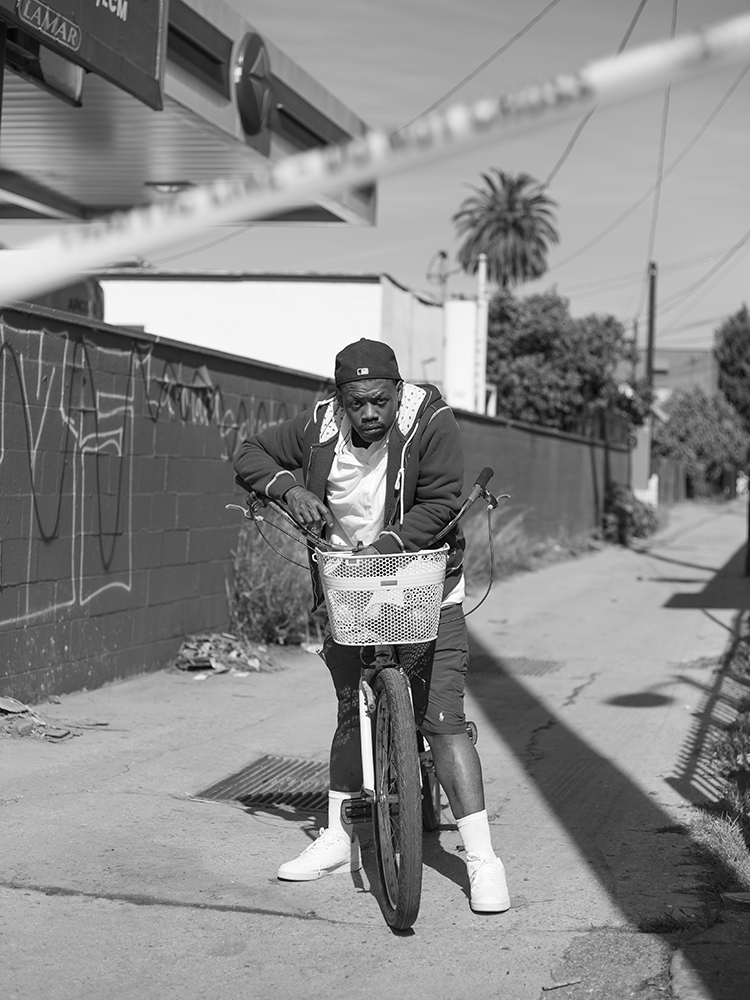

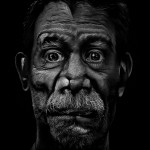

In The Warmth of Other Suns, Christian Lee provides a much-needed dose of optimism in a turbulent world. His photographs, made during the 2025 Kingdom Day Parade in Los Angeles, for the most part focus on youth participants and spectators. For me, these portraits have a compelling sense of resilience—especially when considered alongside this year’s parade theme, Peace and Unity: Let it Start with Us. Lee, whose family emigrated to South Los Angeles, connects with his community through lessons passed down from his relatives. He writes, “This region of the city has not always been unified, however, as my loved ones remind me, we never cease to rebuild.” Lee appears driven to highlight this quality in others—an inner strength that refuses to yield to distress or injustice.

Christian Lee is a 43rd Annual Telly Award® winning visual storyteller and Hoyt Scholar at UCLA. His work has been published in The New York Times, TIME Magazine, Vogue, the Los Angeles Times, the World Photography Organization, Lenscratch, LensCulture, and Booooooom. Lee is an Emma Bowen Foundation Fellow, Sony World Photo Honoree, The KALH Future Grant Recipient, YoungArts Winner, and a Scholastic National Medalist with recognition from over 60 competitions and publications. Awarded the 2025 Lenscratch Student Prize (Top 3), he is a Class of XXXVII alumnus of Canon’s Eddie Adams Workshop, an Up Next Photographer at Diversify Photo, and a Member of NAACP, Film Independent, and AAJA, whose moving and still images explore themes of youth culture, assimilation, and intergenerational trauma, all within communities of color. Lee currently works in Creative Affairs at Warner Bros.

Instagram: @christianmakesfilms

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Samantha Johnson,, Executive Director of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Curator and former Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize. Alayna Pernell, Artist, Lenscratch Editor, Educator, Epiphany Knedler, Artist, Editor for Lenscratch, Educator, Curator of MidWest Nice, Jeanine Michna Bales, Beyond the Photograph Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Vicente Cayuela, Social Media Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, and Drew Nikonowicz, Artist, winner of the 2015 Lenscratch Student Prize.

The Warmth of Other Suns

My family settled in South Los Angeles upon emigrating to the U.S. I remember late afternoon drives down Western Avenue and spontaneous visits to Crenshaw, where we stood before the tiny apartment my father and his siblings grew up in. The relationship my relatives shared with the city unfolded as a complex interplay between sorrow and joy, struggle and success—the frequently synthesized immigrant narrative began taking dynamic shape as we attended the Annual Kingdom Day Parade. Honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy was instrumental to the progress of our respective communities and the deep impact that Dr. King’s heroism had.

It allows us to confront a complex history layered with tension, injustice, and violence. This region of the city has not always been unified, however, as my loved ones remind me, we never cease to rebuild. The wildfires and widespread hatred threatened to prevent us from uniting. The Kingdom Day Parade was cancelled, and many Los Angelinos were mourning.

Still, we found a way to heal.

Attending the rescheduled Dr. King parade was a beautiful demonstration of solidarity in a time where apathy seems prevalent. When I interacted with those children spectating curiously from their porches or the families cheering under our city’s palm trees, I saw a future. I saw hope.

Photographing reminded me that the camera could be used to restore dignity and agency to communities often erased from the larger story of American life.

Daniel George: Congratulations on receiving 2nd Place for the Lenscratch Student Prize!!! To begin, tell us how photography came into your life. What led to your interest in the medium?

Christian Lee: Thank you so much for the honor of a lifetime! I have been reading Lenscratch since high school, and this publication revealed to me an industry I otherwise would have no access to. My endless gratitude to the entire jury and Aline Smithson for believing in me and my work!

Growing up in an immigrant family marked by domestic violence, I found solace in the expressive act of imagemaking. My world chaotically shifted between different schools and homes, although photography offered a steady rhythm of storytelling. I spent my childhood navigating a volatile environment, but discovering the camera saved me, providing an escape from that harsh reality while imbuing me with the courage to face it. I felt whole, and when I pressed the shutter, every painful memory, every laugh or tear, every moment that was informative or insecure—that shutter became the totality of my life experience.

I began creating pictures and directing films in the 4th grade. When most kids were out playing, I was holed up inside watching old independent films and editing portraits of relatives as they navigated family life. My schools rarely offered visual media classes, which resulted in a deep self-education. In 8th grade, I began entering shorts into film festivals and sent out emails to newspaper and magazine editors. My photography was later published in The New York Times, Vogue, and the Los Angeles Times, where I worked as one of the younger HSI Reporters.

My family continued disowning me, and home life grew increasingly turbulent. The trauma I sought to heal from unfailingly resurfaced, and our finances fell through after my mom’s sudden cancer diagnosis. The dreams of art school faded, and I attended UC Irvine to study Finance, where I interned at a Big 4 Accounting firm and became President of the college’s largest film organization, achieving the Dean’s Honor List quarterly, yet still battling uncertainty and heartache. I began creating self-portraits of my mom and I, and to my surprise, she responded positively. We both viewed survival as a creative act, and because of that, her courage inspired mine. A year away from graduating early at UCI with a corporate return offer, I applied to UCLA Arts, lacking studio courses but possessing a rich portfolio and an unwavering passion. Here, I healed, creating the images I wish I had seen as a child. I set out to make the most of these two years, learning with Cauleen Smith, Tarrah Krajnak, Cosmo Whyte, and all the artists who inspired me. I realized my journey could be traced back to a larger history, and that led me to search for answers. The camera became the primary solution for rebuilding and remembering.

DG: How about “The Warmth of Other Suns” series? When and how did that work start?

CL: “The Warmth of Other Suns” unfolded naturally and with great sensitivity. I began thinking about the intersection of daily rituals and cultural traditions within BIPOC communities in South Los Angeles. All the summers I spent playing on my grandmother’s front porch and attending the citywide parades honoring civil rights leaders informed my photographic inquiry.

My family settled in South LA upon emigrating to the United States. I remember late afternoon drives down Western Avenue and spontaneous visits to Crenshaw, where we stood before the tiny apartment my father and his siblings grew up in. The relationship my relatives shared with the city unfolded as a complex interplay between sorrow and joy, struggle and success—the frequently synthesized immigrant narrative began taking a dynamic shape as I attended the Annual Kingdom Day Parade. Honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy was instrumental to the progress of our respective communities, and the deep impact that Dr. King’s heroism had.

It allows me to confront a complex history layered with tension, injustice, and violence. This region of the city has not always been unified, however, as my loved ones remind me, we never cease to rebuild. The wildfires and widespread hate threatened to prevent us from uniting. The Kingdom Day Parade was canceled, and many Los Angelinos were mourning losses of different kinds. Still, we found a way to heal.

Attending the rescheduled Dr. King parade was a beautiful demonstration of solidarity at a time when apathy seemed prevalent. When I interacted with those children spectating curiously from their porches or the families cheering under our city’s palm trees, I saw a future. I saw hope. Photographing reminded me that the camera could be used to restore dignity and agency to communities often erased from the larger story of American life.

DG: You write about an evolving relationship with the city of Los Angeles, in part informed by your relatives perspectives. I am curious how your creative practice has helped your personal perspective evolve about the place where you live. What insights have your pictures given you about your city?

CL: I photograph to understand. Creating images brings me closer to my city and community in a way that no other experience does. I always feel that “The Warmth of Other Suns” is an open dialogue with the past, unearthing a nuanced history and complex legacy that is embedded in Crenshaw and South Los Angeles. My relatives constituted a significant wave of Korean immigrants settling in African American neighborhoods, where they raised families and opened businesses. Socially rejected by white spaces, they sought refuge in the southern part of the city, where they built a fulfilling life almost adjacent to these historically BIPOC enclaves.

I spent most of my childhood in Los Angeles County, and every time I return to Crenshaw and the surrounding area, I rediscover my own extensive family history and that of an entire community rooted deeply in culture. The complexity of both my separation and closeness to the space is revealed through these formal portraits, elevating intimate celebrations. The splendor that our narratives often remain devoid of comes alive in the sunlit gazes of generational residents, who actively preserve the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. through American pastimes.

The title itself is a tribute to Richard Wright and Isabel Wilkerson’s seminal writings about the brave African Americans who emigrated to the West during the Great Migration, thus paving the way for people of color to settle in a space they otherwise could not access freely. And it is with immense respect and tenderness that I honor our shared dreaming. As a product of the Korean immigrants in Los Angeles, I revere those who came before us to pave the way. It is because of the families visualized lyrically in these portraits that I can revel in the warmth of other suns.

DG: Would you mind sharing your research methodology for this project?

CL: Living and being present! The research methodologies for my projects typically depend on the scope and perspective of the work. “The Warmth of Other Suns” was the type of series that required me to be out in the community, dialoging with folks, and creating images rather than behind a screen or in a library and archive. I traveled to the city before bringing my camera. While I recognize the benefits of being prolific, I wanted to approach both the community members and the deep history with respect. I was not there merely to make photographs but to understand the legacy that my own family and those who came before us paved.

The sunshine also aided in the research! It was beautiful, warm weather complemented by layered and thoughtful conversations, where everyone radiated true joy and openness.

DG: In this edit, we see a lot of portraits of young people. For me, this strengthens the theme of hope that you mention in your artist statement. At this moment in time, it is easy to feel helpless and discouraged by what is happening in our country and the world. As you look at these pictures, what sort of hopefulness do you feel they offer?

CL: As a self-taught 21-year-old artist from a traditional immigrant family with no pathway into the industry, I tend to underestimate myself. I love creating portraits of youth because it allows me to locate the confidence and dignity that I strive for daily. Coming-of-age narratives always hold a special place in my heart; however, I realize that the most popular stories rarely feature communities of color. How radical could it be if I photographed the exceptionally gifted kids of Crenshaw in the same way that one might envision royalty? That desire to reclaim our collective pride has always been my inspiration behind picking up a camera.

In the same way that I spoke earlier about dialoging with the past, making pictures is an act of remembrance, and I choose to remember with reverence. I still, in many ways, am a kid myself, and I remain stuck between college life and this looming post-graduate malaise I fear the moment I leave UCLA. The future is terrifying, and the overwhelming violence against our immigrant and BIPOC communities has almost stolen my light. I am afraid for my family, for my friends, and for my home. Creating these portraits of youth in Crenshaw healed me. Their courageous gazes remind me why I fell in love with the camera, for its ability to render us bold, beautiful, and brave in the most human way possible. There is regality in how I perceive a middle school boy creating joyful noise for those he loves or a young girl crowned in jewelry.

For a community whose daily rituals and traditions often go unnoticed, these poetic details and the powerful lives and perspectives attached to them remain the lifeblood of my art.

DG: In your photographic work, you tend to gravitate toward portraiture. Would you share your thoughts on why a focus on people is your preferred mode of storytelling?

CL: The act of “looking” for communities of color remains deeply courageous. I think about how interconnected the history of photography is with the policing of our gazes. Portraiture became the most effective way for me to reclaim a basic human right denied to BIPOC folks while working within an artistic language weaponized against us. I am currently finishing a project exploring Southern California’s East Asian migrant communities, and I realize how many people of color lost their lives by looking a white person in the eyes. This gesture alone, when reclaimed through lyrical documentary, reshapes into a radically transformative act of resistance.

I still think about the first time I encountered Dawoud Bey’s “Couple in Prospect Park, 1990,” and how enraptured I was by the complexity of this photographic portrait. I am not from New York nor was I alive in the 90s, but I feel connected to these two strangers in a way that is almost spiritual. Bey created a masterful series of 4×5 Polaroid images, elevating fellow African Americans he encountered while creating images in the city. The result is perhaps the most powerful body of work I have self-studied in the 21 years I spent self-educating.

That prodigious ability to showcase the complex soul of an expansive community remains a life goal of mine. I am forever amazed by those photographers whose lens identifies evocative details and gazes in order to dignify the people often erased from American life. Many unfamiliar with Crenshaw, they might perceive a working-class city densely populated by minorities. When I gaze upon the space, I see all the beautiful faces that work tirelessly to preserve the culture and thus dignify their lives and stories, reclaiming agency through the courageous act of living.

DG: I’d like to hear about your educational experience. How has your creative practice evolve since you have been in school?

CL: Before transferring to UCLA, I had no professional studio experience. Most schools I attended never offered media programs and courses, which left me to my own devices. Using a cracked iPhone 8 and a thrifted camera, I began creating pictures and directing films in 4th grade. I continued telling stories throughout middle and high school without any classroom training or artistic mentorship. That ultimately became the greatest gift. My independent spirit propelled me to develop a distinct voice that continues informing all the photographs I make. I never felt the need to “wait” for permission and simply told the stories I wish I had seen growing up.

My first year at UCLA was challenging and deeply rewarding. The undergraduate Art program admits around 40-50 students annually, which allows for a strong community amongst a sizable student population. You continue enrolling in classes alongside the same folks, and if you are discipline-focused like me (I never learned any other medium besides photo and video), you will become acquainted quickly. I had no experience with studios and the format of critique; however, I encountered many peers who attended arts high schools or hailed from creative backgrounds, boasting resources I never knew existed. Critiques felt generative but also grueling, and I was often degraded for not knowing all the technical terminology or current aesthetics.

Art schools can be cliquey, and UCLA still is a predominantly white institution (PWI). “Whiten the skin,” “There’s nothing radical about your photographs,” or a mountain of offensive comments still linger in my mind. However, I found exceptional kinship with a group of BIPOC students in the Art program, and that was an opportunity to grow and heal. The faculty always went the extra mile, and they truly offer world-class teaching. Any pushback compelled me to advance “The Warmth of Other Suns.” My whole life, people have doubted me, and I finally reached a point where I could advocate for myself and others through photography. The existing negativity became fuel, and I ultimately made my strongest and most intentional work. The photographs evolved out of an inner discovery of dignity and purpose.

DG: Was there any advice that you received (perhaps even in the form of a critique) that you feel had a significant impact on the trajectory of your work? Would you mind sharing?

CL: My high school chemistry teacher, Miss Kazibwe, always encouraged me to pursue my art. We shared many thoughtful conversations about the power of visual storytelling. She encouraged me one day in the library, “You must always consider whose gaze it is.” I knew that I loved the camera for its ability to dignify people, and her words reminded me of my mission to champion communities of color. “Do not be afraid to take up all the space you need. Your voice is the most powerful tool you have,” she wrote in the back of my senior yearbook. Years later, I think back.

I am an Asian American photographer with familial roots in South Los Angeles who is creating portraits of a predominantly African American community. Already, there is a complicated ethic to “The Warmth of Other Suns,” which I need to fully acknowledge and account for. My family may have settled in the specific region for generations, but I am trying to convey a perspective that I will never inherently understand. I notice many white photographers, specifically in the documentary tradition, making images of communities they are not from or cultures they exoticize. Rarely do these artists acknowledge their own positionality in regard to the work, and I want to ensure I do not make the same mistake. The camera is an effective tool to restore dignity and agency to those whose image has been violated. Understanding my perspective on the series brought me closer to a final product that feels honest. The proximity I have to Crenshaw and the family ties to this beautiful city are all wound up in the portraits, which remain complex in their aesthetic formality, paying tribute to the tradition of fine art documentary work while also contesting its pervasive whiteness and Westernization of ethnic gazes.

I must recognize Ameerah Abdul-Rahman, a close friend who assisted on “The Warmth of Other Suns” and an incredible artist, elevating the African diaspora. She and I always shared clear-eyed dialogues surrounding the work, which kept me intentional and conscious. I also collaborated with UCLA’s Afrikan Student Union and the Black Bruins Resource Center on a project and show earlier this year, where I created portraits of undergraduate students. They played a central role in reshaping my perspective and encouraging me to finish “The Warmth of Other Suns.”

DG: Being a student can be exhausting, and burnout is real. What motivates you to continue creating?

CL: My mom. I was raised by the most compassionate and powerful woman, who taught me every day to lead with empathy and integrity. It is an honor to receive the 2025 Lenscratch Student Prize; however, I know that I am only tall because I stand on her shoulders and all those visionaries who came before me. I honor the ancestors and our beautiful, proud community.

I still remember returning home one weekend from UC Irvine, where I dragged my feet through a grueling finance internship and classes. My mom was undergoing chemotherapy treatment for her breast cancer at the time, and she sat at the dining room table with papers sprawled. They were applications for the Visual Art and Film programs that she neatly highlighted and filed.

Whenever I find myself on the precipice of burnout (crashing out, as my generation may say), I think back to this moment and the countless times when my mom sacrificed for me to follow a wild dream. I can think of no greater creative, spiritual, and personal inspiration.

DG: Do you have advice for younger artists just getting into their creative studies?

CL: I am a 21-year-old self-taught photographer from an immigrant family, born without a silver spoon or any entrance into this creative world that I admire so much. Committing to my art with the hope of earning a stable living seems impossible, and may I add terrifying when there are still very few from your community who have succeeded. The 2025 Lenscratch Student Prize is monumental and has been a life goal of mine. Despite the triumphs, I still awaken every day, willing to roll my sleeves and do whatever it takes to create the art and pay my bills. From my 21 years of life and creation, I learned that courage, love, and endurance will bring you all the way home. These values and ethics should be visible throughout your work and life.

Most artists are launched into an oversaturated market, and we must navigate a struggling economy to sustain our practices and lives. I am interning full-time at Warner Bros. as an Emma Bowen Fellow while directing a short film and creating photographs on weekends. Not to mention all the applications and responses I am sending out the moment I arrive home in the late evenings, as well as the countless tables I waited in college, or grants I hustled to fund the art. It never ends, and I feel I must be prepared for whatever comes my way. This is exciting, though, and I count myself blessed to have encountered such generous support and genuine inspiration.

Young artists, we are in this together! I am inspired by our global community, and I hope that we continue creating and advocating with integrity and character. The future depends on us!

DG: Finally, is there a mentor that you’d like to acknowledge? In what ways has their guidance informed your work?

CL: I never enrolled in a studio course before transferring to UCLA, and I studied Finance at UC Irvine for the first two years, where I tirelessly petitioned the Art and Film Departments, all to no avail. I found myself sitting in on an Art History lecture about Carrie Mae Weems when I immediately fell in love with the professor, whose class I enrolled in the next quarter. Dr. Bridget R. Cooks, who teaches as core faculty, changed my life. A renowned curator and scholar, she was the first person to truly champion my work and identify a potential I myself had not seen. I will never forget her kindness—how Dr. Cooks presented my photographs in class, connected me with any Art faculty she could reach, and generously offered a listening ear during our many office hour conversations. She introduced my photography to a personal hero, Emmy Award-winning cinematographer and photographer, John Simmons, for whom she curated a gorgeous retrospective. Mr. Simmons formerly taught at UCLA and has since become a crucial mentor to me, trading prints and attending my first solo exhibition after I transferred to art school. Dr. Cooks and Mr. Simmons are constant advocates for artists who rarely see themselves in the culture, and their teaching felt more valuable than any formal arts education I received.

Not to mention all the outstanding UCLA faculty and staff I worked with this past year: Cauleen Smith, Tarrah Krajnak, Cosmo Whyte, Siri Kaur, Michael Alvarez, Laub Taliesin, and Anuradha Vikram. I also attended The Eddie Adams Workshop and felt nurtured by our greatest storytellers, most especially Brent Lewis and Lauren Bulbin. There are far too many to thank!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Erika Nina SuárezJuly 27th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Montenez LoweryJuly 26th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Ian Byers-GamberJuly 25th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Beihua GuoJuly 24th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch 3rd Place Student Prize Winner: Hannah SchneiderJuly 23rd, 2025