The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Beihua Guo

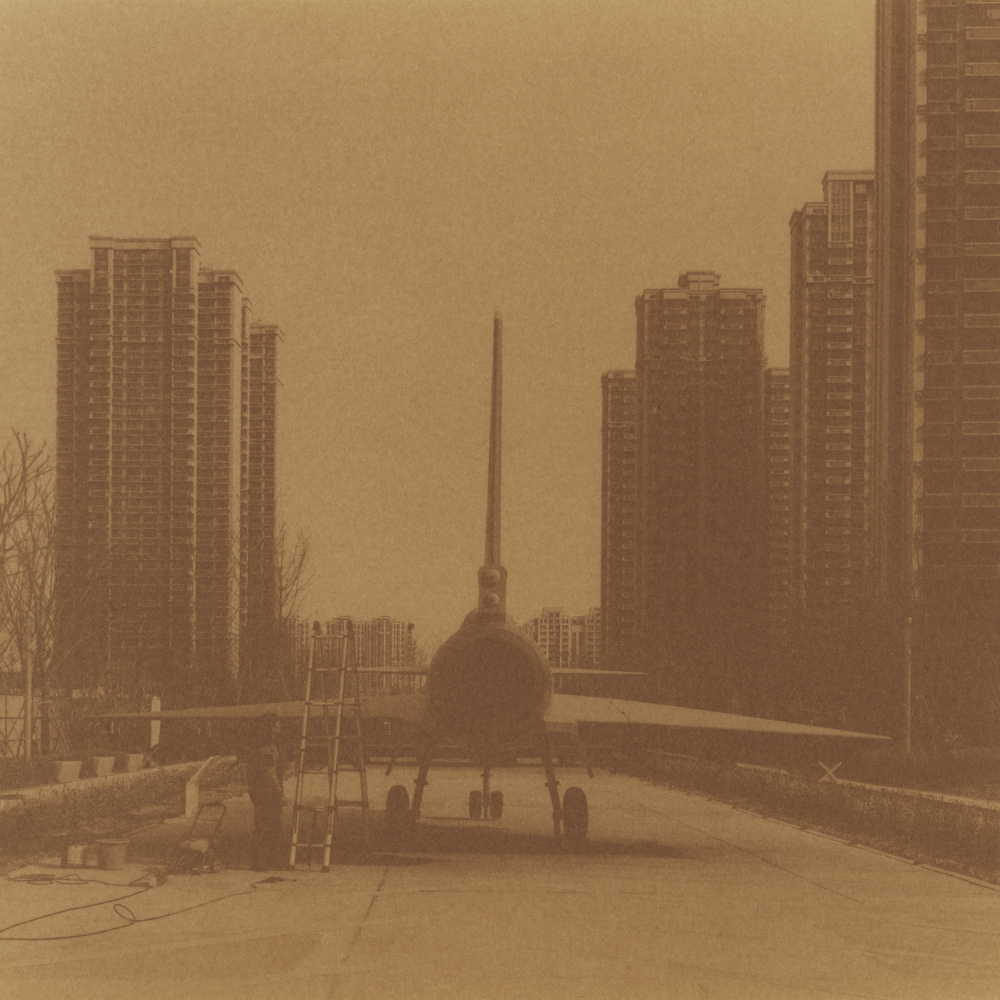

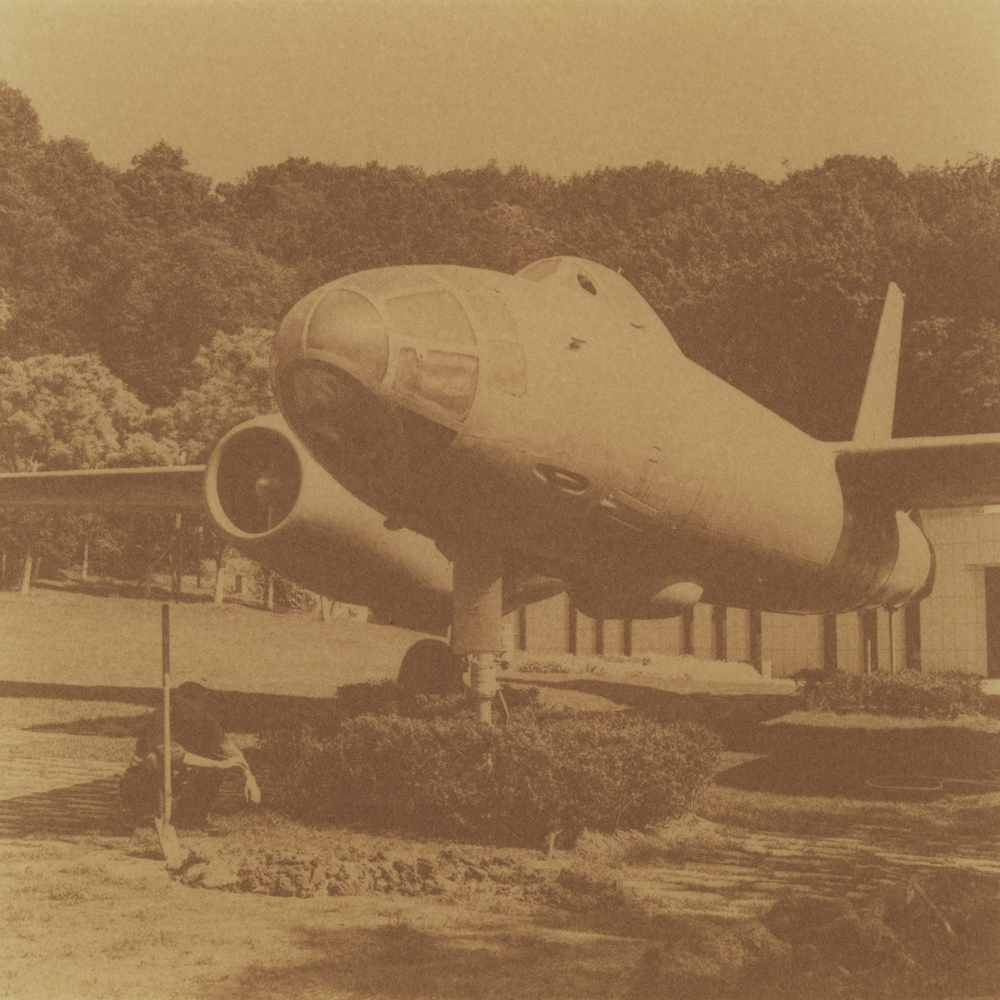

©Beihua Guo, 3641-11655: Jinan Zhangzhuang Air Base, 1956; Zhangzhuang Airport Culture Park, Jinan, 2024 (printed 2025)

It is with pleasure that the jurors announce the 2025 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner Beihua Guo. Guo was selected for his project, Designated Ground Zeros. He is currently is pursuing an MFA in Photography, Video, and Imaging at the University of Arizona (home to the O’odham and the Yaqui). The Honorable Mention Winners receive a $250 Cash Award, a feature on Lenscratch, a mini exhibition on the Curated Fridge, a Lenscratch T-shirt and Tote.

I’m truly honored to introduce Beihua Guo, a Lenscratch 2025 Student Prize Honorable Mention and remarkable visual artist whose work deeply engages with the complex, often hidden histories embedded in the landscapes we might otherwise overlook. Born in Shanghai and now pursuing an MFA at the University of Arizona, Guo brings together his unique background in both environmental analysis and studio art to explore how sites marked by colonialism, war, extraction, and displacement continue to shape our present.

His ongoing project, Designated Ground Zeros (2023-present), tracing the 368 nuclear target sites identified by the United States Strategic Air Command in 1956, is as ambitious as it is vital. In his image-making, Guo reveals layers of history that are both tangible and invisible, showing how industrial spaces have been transformed into contrary spaces, all while carrying echoes of global conflict and shifting political power. What makes his work especially compelling is the way he uses his photographs as an entry point for viewers to experience before diving into their complex backstories.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Samantha Johnson,, Executive Director of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Curator and former Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize. Alayna Pernell, Artist, Lenscratch Editor, Educator, Epiphany Knedler, Artist, Editor for Lenscratch, Educator, Curator of MidWest Nice, Jeanine Michna Bales, Beyond the Photograph Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Vicente Cayuela, Social Media Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, and Drew Nikonowicz, Artist, winner of the 2015 Lenscratch Student Prize.

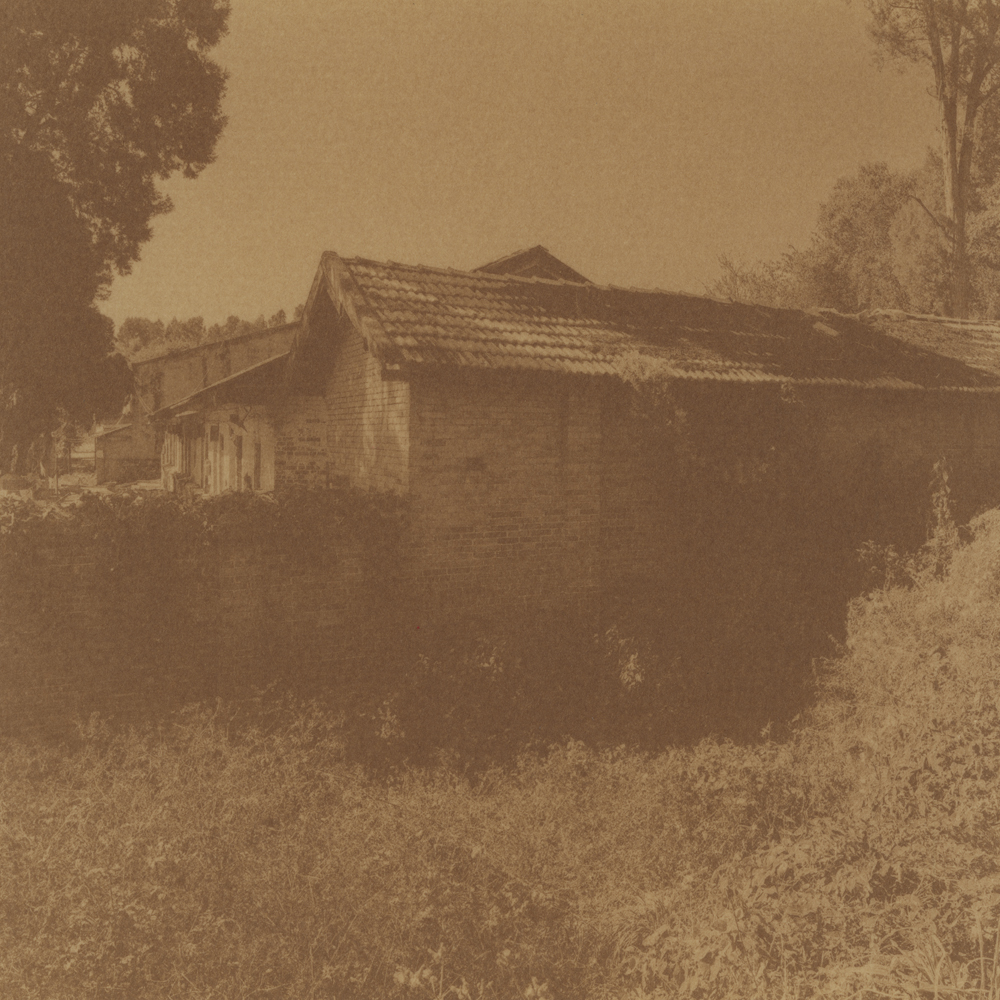

©Beihua Guo, 3012-12008: Zhakou Railway Station, Hangzhou, 1956; Railway Museum and the Sent-down Youth Memorial, Hangzhou, 2023 (printed 2024)

Designated Ground Zeros

The Atomic Weapons Requirements Study for 1959, produced by the United States Strategic Air Command (SAC) in 1956 and published by the National Security Archive at George Washington University in 2015, is the most comprehensive record of Cold War nuclear targets ever declassified. Spanning over 800 pages, this document lists the coordinates of more than 4,500 nuclear targets across the Soviet Union, China, and Eastern Europe.

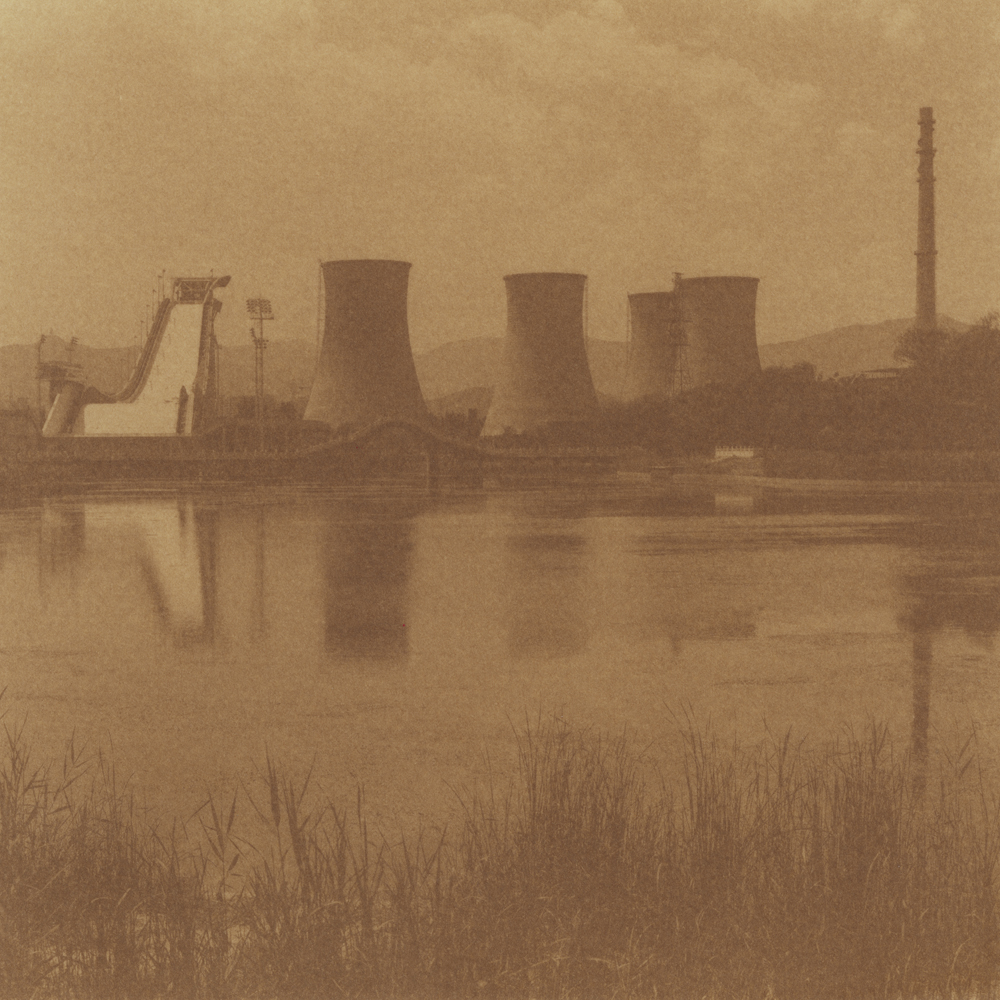

I travel to the nuclear targets in China identified by the SAC in 1956, documenting these sites through photography and creating radioactive uranotypes using the uranium printing process. Many of these sites have undergone dramatic transformation: the once-abandoned Shougang Steel Mill in Beijing became the Big Air venue for the 2022 Winter Olympics; warehouses, airport hangars, and fuel tanks along Shanghai’s Huangpu River now house contemporary art galleries and museums; open-pit mines in Fushun and Dayu have been repurposed into educational and recreational zones. These seemingly mundane landscapes are, in fact, sites marked by deep historical trauma—legacies of imperialism, Cold War tension, and China’s evolving identity.

Number of nuclear targets photographed: 77 of 368 (as of July 6, 2025).

©Beihua Guo, 3111-12128: Beipiao Wharf, Shanghai, 1956; Xuhui Riverside Open Space, Shanghai, 2023 (printed 2025)

This may be a bit personal as initial questions, but I think that our context as artists really truly informs the work that we make in some capacity. Would you mind sharing with me about your background or upbringing and what brought you to making the work that you create today?

I grew up in Shanghai, China, a forest of concrete and glass. When I moved to the U.S., I was immediately drawn to the national parks. Yosemite, especially, became a kind of refuge. I kept going back year after year, chasing that feeling of stillness and awe. For a while, I photographed these landscapes with a kind of reverence. But over time, that romantic image began to fall apart as I studied art and environmental history at Pitzer College. The more I learned, the harder it became to see these places as untouched or innocent. Behind the grandeur were layers of violence, history I hadn’t heard before—lynching in California, Japanese incarceration at Manzanar, and corruption and violence behind the Los Angeles Aqueduct. I realized that beauty in these images often hides what’s been erased. That shift changed everything for me. As an artist, I feel a responsibility to dig into those buried histories.

©Beihua Guo, 3954-11609: Shijingshan Steel Mill, Beijing, 1956; Big Air Venue for the 2022 Winter Olympics, Beijing, 2023 (printed 2025)

That’s such a powerful shift to go from reference to uncovering the deeper, often hidden histories behind those landscapes. You also have a background in Studio Art and Environmental Analysis from Pitzer College. Was your experience with art influenced by Environmental Analysis or vice versa? And if so, was there a moment that defined your merging of these two disciplines together?

My earlier projects often explored environmental themes, rooted in my background in environmental history. At Pitzer, I focused on the “Sustainability and the Built Environment” track within the Environmental Analysis major, which gave me a foundation in urban planning and a deeper understanding of how cities are shaped by policy, power, and people.

This project builds on that and takes a closer look at how colonialism and gentrification continue to shape the urban landscape in contemporary China. It’s also about reimagining what cities can be, and how sites of industry and displacement might be transformed into places of public memory and access.

©Beihua Guo, 3010-12015: Industrial and Military Storage Areas, Xiaoshan, 1956; Chairman Mao Statue, Hangzhou, 2023 (printed 2024)

That’s such a fascinating intersection. This leads me to wanting to know more about the physicality of your work. You mention in your statement how you create “… radioactive uranotypes using the uranium printing process”. What brought you to this method of image making?

This project started out as a medium format black-and-white film series. But I wasn’t satisfied with the documentary feel or the “New Topographics” aesthetic. It felt too detached. I wanted to introduce something more radioactive and more unstable into the work. I came across the uranium printing process online. Artists like Abbey Hepner had used it in powerful ways, and I was intrigued. I learned the uranotype process from Bob Kiss’s YouTube tutorial, and after lots of trial and error, I developed my own approach. It’s significantly more cost-effective and has a distinct visual signature.

©Beihua Guo, 2838-11555: Nanchang Qingyunpu Airport, 1956; Hongdu Aviation Culture Park, Nanchang, 2023 (printed 2025)

So far, you have photographed 77 of 368 nuclear targets in China, which is fascinating. In more of a logistical sense, what is your method of working when you go to China to photograph these sites?

I visit my family and friends in China every year during vacation, which gives me the opportunity to work on this project bit by bit. Originally, my goal was to visit every single site, but I quickly realized that wasn’t practical. Some are still active military bases or classified industrial zones. Fortunately, most of the targets are public spaces located in major cities, and traveling between them is relatively easy and affordable in China, thanks to the high-speed rail system and good public transportation. One of the biggest challenges, though, has been the planning and research. It’s not always immediately clear why a particular site was targeted, so I rely on old maps, historical documents, and even declassified reconnaissance satellite images. There are still about 10% of the sites I haven’t been able to figure out. I don’t know what they are or why they were on the list. After careful research and planning, I head out and photograph the ones I can access.

That’s completely understandable. For what it’s worth, it’s incredible how much ground you’ve already covered. The sheer impracticality of trying to photograph every site makes the project even more compelling because it builds on the conversation. Something is intriguing about facing those unknowns, especially the sites you can’t fully identify or access. Though with the sites you have visited and photographed, there was something else that caught my attention. I found it interesting how many of these nuclear target sites that you’ve studied, from my perspective, have also been impacted by capitalism, such as your mention of the Shougang Steel Mill in Beijing becoming the Big Air venue for the 2022 Winter Olympics. I’m so curious about your research, if this is something that you noticed as a trend, or if other site erasures have happened that haven’t had a capitalistic influence.

This is a great question. One of the best examples is Longhua Airport, a former civil–military airport just two miles from where I grew up. When I returned in 2023, I was surprised to see the old fuel tanks had been turned into an art museum, TANK Shanghai, and it was hosting a McDonald’s × VERDY exhibition.

©Beihua Guo, 3110-12127: Aviation Fuel Storage Tanks, Longhua Airport, Shanghai, 1956; McDonald’s × VERDY, TANK Shanghai Art Center, 2023 (printed 2025)

©Beihua Guo, 3203-11845: Government Control Centers, Nanjing, 1956; National Defense Park, Nanjing, 2023 (printed 2024)

Many of the industrial sites I’ve photographed have undergone similar transformations, becoming shopping malls or cultural centers. The Shanghai Shipyard, for instance, is now the MIFA 1862 Shopping Mall and Performance Arts Center.

In addition to traces of capitalism, I started uncovering layers of colonialism and war. Many of the airports and industrial sites were originally built by foreign invaders and colonizers. Who would’ve thought that a dirt hill in a remote village outside Beijing was once an aircraft hangar constructed by the Japanese military?

And it’s not an isolated case. There are hundreds of similar structures scattered across China, often hidden in plain sight or quietly erased by real estate development.

Wow. This speaks volumes to the complexities of these shifts. There’s so much pertinent information that you provide with this work, including a story map. It’s so helpful and elaborate in guiding viewers (myself included) through understanding the history attached to the work and where those sites are in a contemporary context. Are there other ways you envision your work existing and being engaged with by viewers?

I created this story map because I wanted to show just how layered and complex this history is. There’s one particular target I haven’t photographed yet, but it continues to fascinate me. It was originally a steel mill built by Japanese forces in 1916 during their occupation. After World War II, the Soviets took control of the site and looted some of its equipment. A few years later, during the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalists destroyed the mill. Then it was rebuilt and began supplying weapons and materials for the Chinese military during the Korean War, used to fight against the U.S. in the early 1950s. By 1956, it had become a U.S. nuclear target.

In addition to collecting historic photographs, I’ve been working on satellite image comparisons to trace how these sites have changed over time. Shanghai Jiangwan Airport, for example, was originally built by the Japanese army during the occupation, and later became the headquarters for the United States Army Air Forces at the end of World War II. Today, the area has transformed into a college town and a wetland park. It’s shocking to see just how much the landscape has changed between 1965 and 2021.

I’ve also been working on an installation piece using more than 300 satellite images to offer additional context to the project. But I’m careful not to be too didactic in exhibitions. The prints still come first. I want viewers to feel the weight of these places before diving into the archive.

©Beihua Guo, 3115-12132: Shanghai Shipyard, 1956; MIFA 1862 Shopping Mall, Shanghai, 2024 (printed 2025)

I really admire your dedication, and it’s clear how much time and care you’ve invested in uncovering the layers that so often get overlooked. History like this is so crucial because it shapes how we understand and engage with the present. It allows viewers to connect on multiple levels with your prints operating as an entryway in a way that is both thoughtful and compelling. As we wrap up, I’m curious if, throughout your studies, there have been mentors or educators who influenced how you navigate as a visual artist.

There are so many. I want to especially thank Sama Alshaibi, Marcos Serafim, Martina Shenal, David Taylor, Mary Virginia Swanson, Tarrah Krajnak, and Ken Gonzales-Day—educators and mentors whose support and guidance have shaped my journey.

©Beihua Guo, 2451-10248: Former WWII Barracks of the Flying Tigers, Kunming Chenggong Air Base, 1956; 2023 (printed 2025)

Amazing. Thank you so much for taking the time to share your work and insights with me. Congratulations on receiving this incredible honor, and I wish you all the best as you continue this powerful and necessary journey. I look forward to seeing where your work goes next!

©Beihua Guo, 3416-11711: Military Base, Xuzhou, 1956; Old East Gate Fashion District, Xuzhou, 2024 (printed 2025)

©Beihua Guo, 3630-11751: Boshan Electric Machine Factory, Zibo, 1956; Historical Site and Residential Area, Zibo, 2024 (printed 2025)

Beihua Guo (b. 1998, Shanghai, China) is a visual artist working in photography, video, and installation. He holds a BA in Studio Art and Environmental Analysis from Pitzer College (home to the Tongva) and is pursuing an MFA in Photography, Video, and Imaging at the University of Arizona (home to the O’odham and the Yaqui). His work investigates how histories are remembered, buried, or erased, particularly in landscapes marked by colonialism, extraction, and displacement. He is a recipient of the John Goto Prize, the Lucie Foundation Photo Made Emerging Scholarship, the Kurt Markus Photography Scholarship Fund, the Janie Moore Greene Scholarship Grant, and a finalist for the Aftermath Grant, Photolucida’s Critical Mass, the OD Photo Prize, BarTur Photo Award, the Three Shadows Photography Award, and the PDNedu Student Photo Contest. His work has been exhibited internationally at venues such as the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, the Royal Photographic Society, Cleve Carney Museum of Art, Photo Beijing, Photo Open Up International Photography Festival, Space Place, and Nizhny Tagil Museum of Fine Arts, among others. He has participated in artist residencies at Petrified Forest National Park, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Yellowstone National Park, Yangshuo Sugar House, and Sunyata Hotel Wuli Village.

Instagram: @beihua_guo

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Erika Nina SuárezJuly 27th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Montenez LoweryJuly 26th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Ian Byers-GamberJuly 25th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Beihua GuoJuly 24th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch 3rd Place Student Prize Winner: Hannah SchneiderJuly 23rd, 2025