Photographers on Photographers: Linda Jarrett in Conversation with Michael Flomen

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today we share the conversation with Linda Jarrett and Michael Flomen. Thank you to both of the artists.

When we think of collaboration in photography, it is often understood as a shared effort between people – through shooting, editing, or exhibiting works. But for Michael Flomen, collaboration expands far beyond human partnerships. His practice engages with the non-human: the elemental, the material, and the natural world itself. Working outside the traditional confines of the darkroom, Flomen creates cameraless images directly in nature, capturing ephemeral phenomena such as the bioluminescent trails of insects on photographic film. The results are both ethereal and deeply connected to the world around us.

I first encountered Michael’s work when I began exploring cameraless photography myself. While writing a paper on collaboration during my MA in Photography, his approach profoundly resonated with me. Though Michael is based in Montreal and I am in New Zealand, speaking with him felt like reconnecting with a kindred spirit – one also engaged in a quiet, reverent dialogue with nature through photographic practice.

Michael Flomen was born in Montreal in 1952. He began taking photographs in the late 1960s and has been showing his work on several continents since 1972. He has been a darkroom printer and collaborator for many artists including for Jacques Henri Lartigue’s traveling exhibition in Canada and the United States in the mid ’70s. Flomen’s first book of “street photographs,” which followed the Cartier-Bresson formalism of photographic picture making, was published in 1980, followed by Still Life Draped Stone in 1985. Flomen switched camera formats in the early ’90s, photographing snow and producing works under the title RISING. For the last 25 years, this self-taught artist has used camera-less techniques to collaborate with nature. Various forms of water, firefly light, wind, and other natural phenomena are the inspiration for his picture making. Michael Flomen’s work is in the collections of George Eastman House, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, the Norton Museum of Fine Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Canada, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among others.

LJ: I’m really interested in your journey as an artist Michael, in particular what drew you away from using a camera and toward collaborating so directly with nature through photograms? Was there a specific moment?

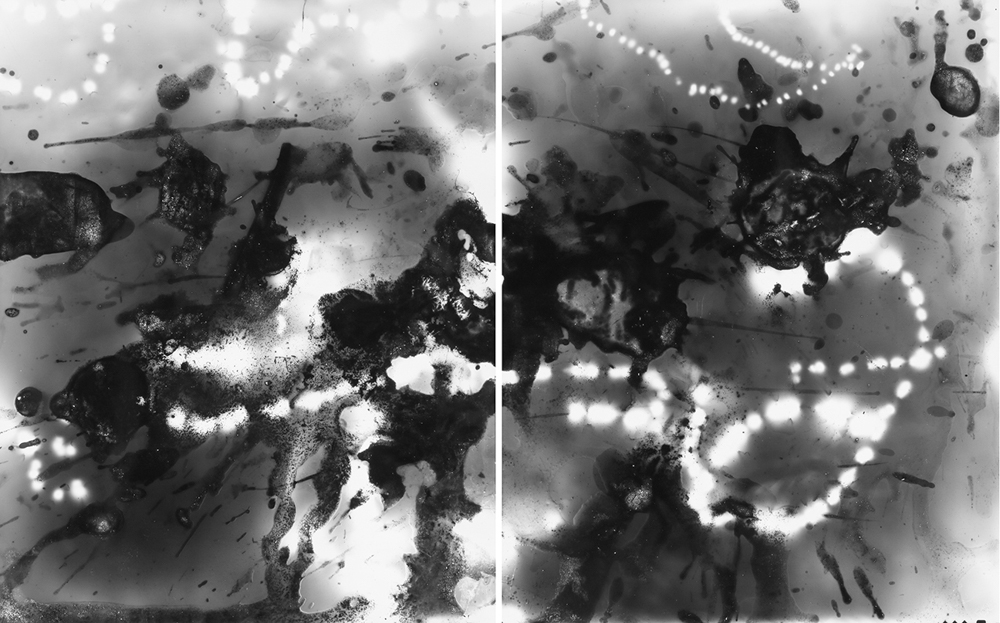

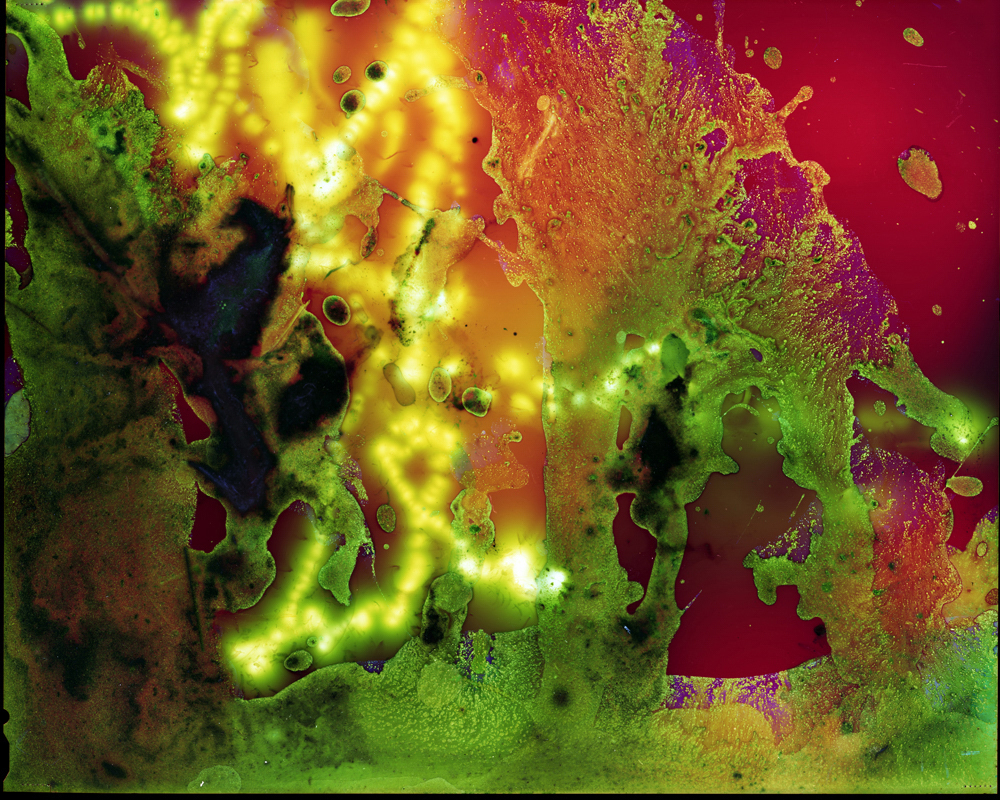

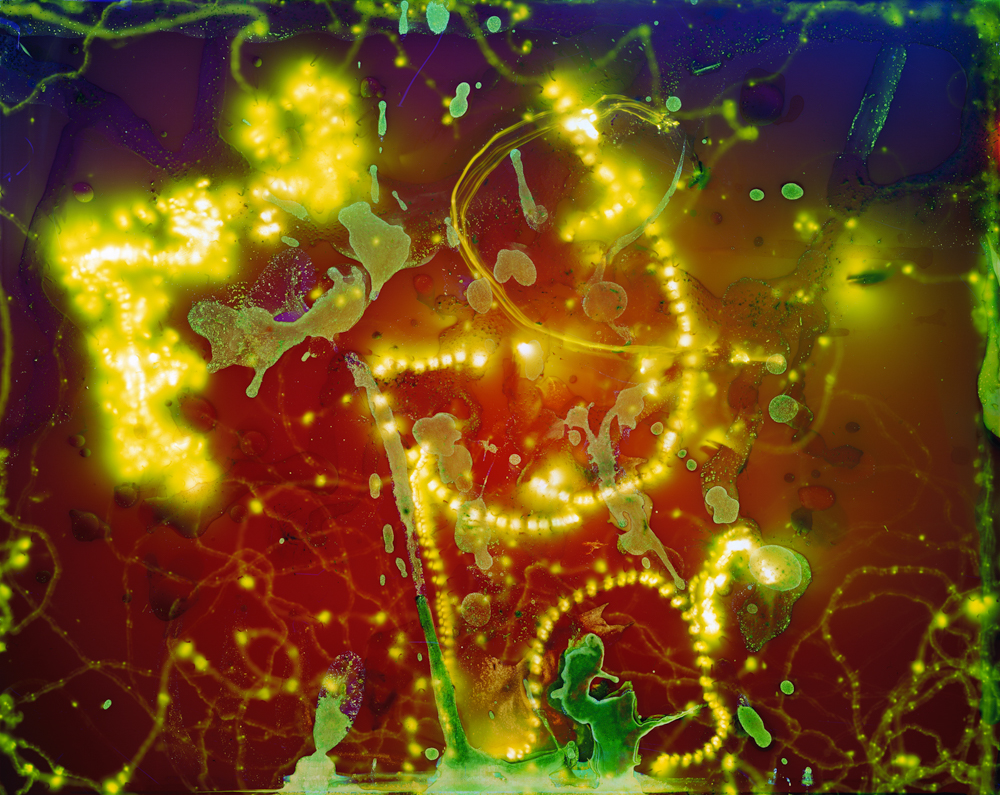

MF: After spending approximately 25 years making street photographs in the spirit of Henri Cartier Bresson with a 35mm film camera, I moved to larger film formats and eventually started making other worldly landscape photographs with an 8 x10 inch camera and film. On a particular early summer evening, I witnessed the fireflies rising out of the tall grasses in a field in Vermont where I was living. I knew that I did not want to photograph the event with a camera, and thought what if the bioluminescent light would expose a film and make marks? I quickly got a sheet of black-and-white film, went down to the fireflies, caught one and placed it on the film for a while. I took the exposed film back into my darkroom for processing and to my amazement the light had exposed the film. That is the moment in 1999 that I started to collaborate with nature.

LJ: Thank you, Michael, for sharing your interesting journey. From our conversation I think that your pivotal moment of transition from camera to cameraless occurred when you decided to photograph fireflies. I also notice that you appear to work a lot during night-time, and your work feels quite scientific and deeply tied to time. Would you agree?

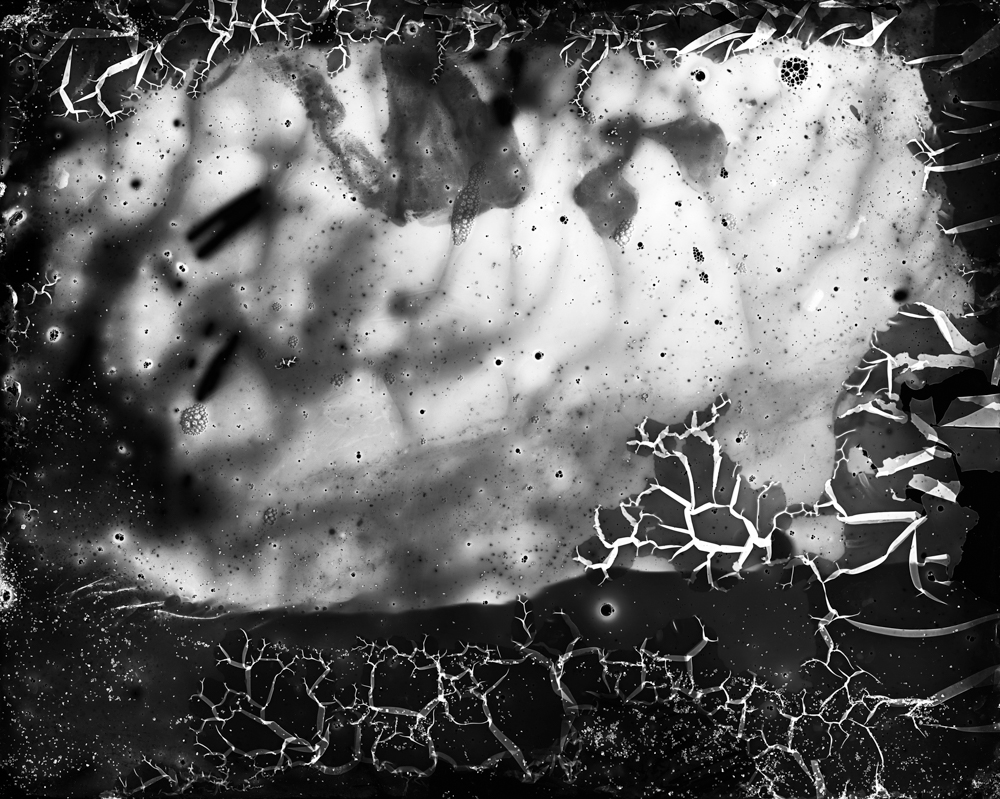

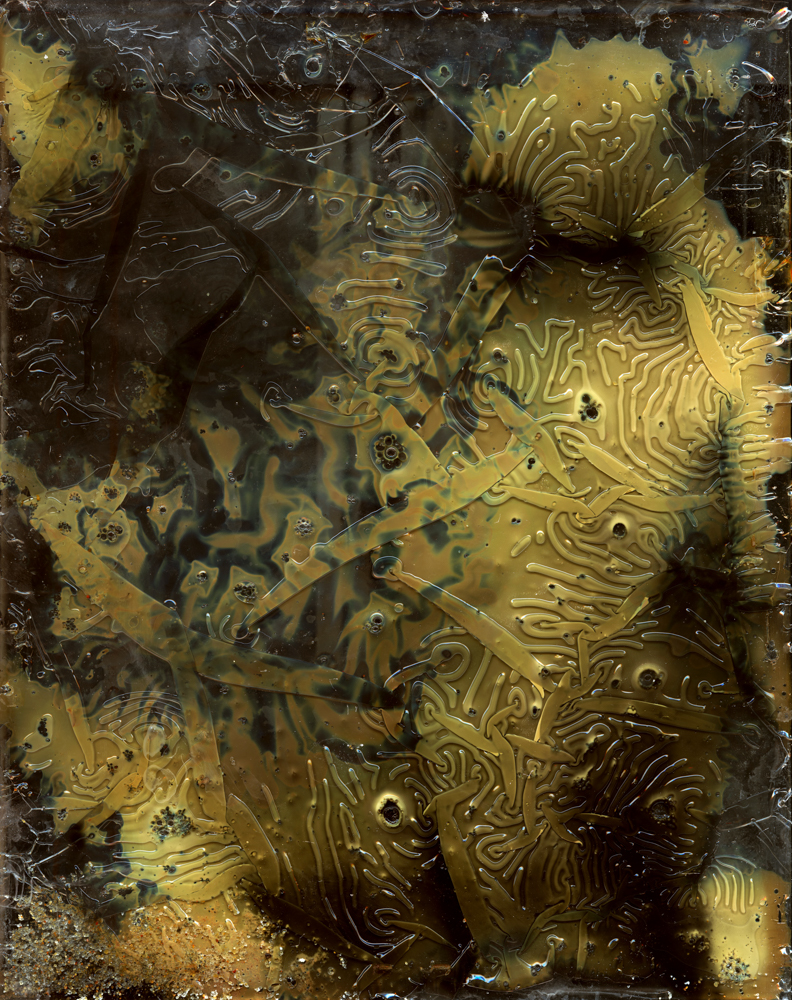

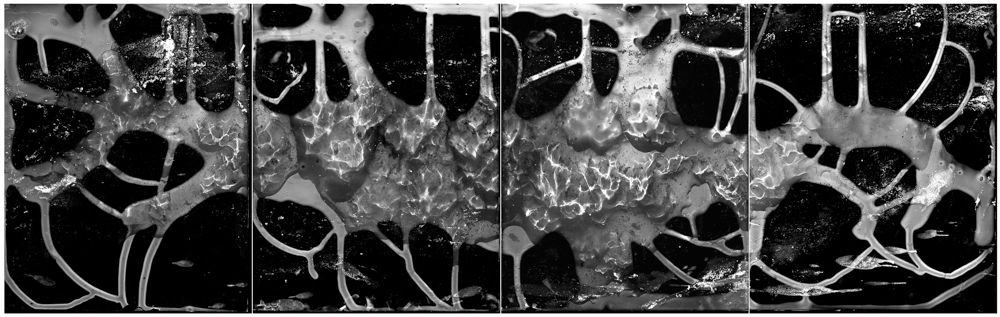

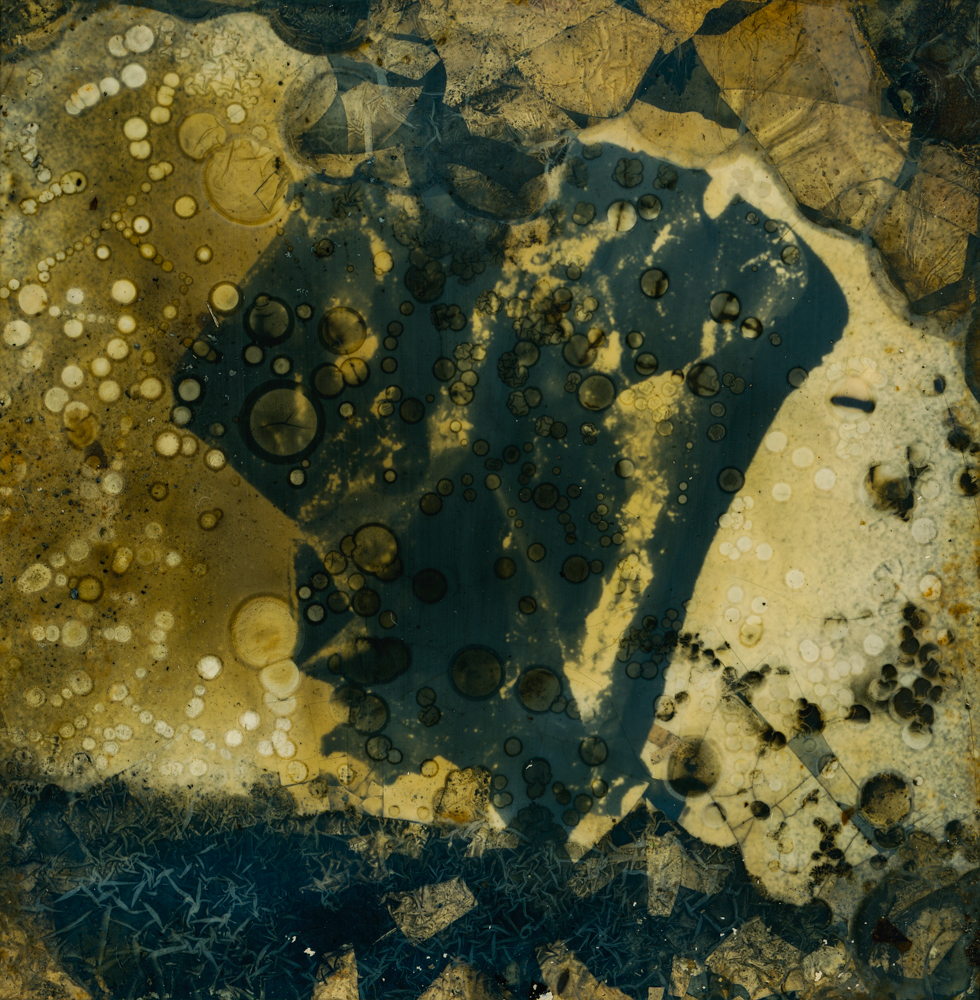

MF: Yes. Normally, if there is a cloudless moon or a bright moon, maybe four or five days before a full moon, I will go into the woods and make a photogram from a combination of moonlight and a small flash. I call them ‘moon burns’, as the moonlight make little dark spots on the paper. I am also interested in geographic landscapes that have a lot of energy. I work in a littoral zone, where land meets water, where we supposedly came out of. I am interested in the theory of evolution, so I believe we are from the thermals and cells we created, and things that happened underneath the ocean. If you look at my images called, Pharmed and Big Sur, they are sort of otherworldly creatures, there are a few of them in my book (Photograms and Photographs, 2020-1970). The series is about creating new life. I fantasize to make a new life form that’s way better than us, on a certain level. So that’s what that series is about. I am not proving anything, I’m not a scientist. Nothing I am doing is for real, but it’s real. I work in highly energized landscapes under the cover of darkness.

LJ: My own practice follows a similar path, though I typically work during daylight hours, as I collaborate with the sun. I’m particularly drawn to the indexical and material qualities of photography – seeking to embed the trace of the subject directly into the image. This often involves placing film or photographic paper into the environment itself, allowing the landscape to inscribe its own mark. Your photograms frequently involve situating photographic paper directly within natural settings. What kinds of challenges have you encountered while working in such a tactile, and uncontrolled way?

MF: Several. Well, basically that nature is very powerful. So, I must be mindful of the power of nature, whether it’s water or wind. One night in winter, about 2008 or so, I was making a picture and even though I take photographic paper out into nature, I still treat it as the perfect print, no dings or blemishes on it. I had set up a large piece of photographic paper and just as I was about to expose it, a wind came along, and the paper went flying across the landscape. I’m in half a metre of snow and I’m running after it, I’m cursing, and my paper is ruined. Once I calmed down and I caught the piece of paper, I was determined to put it back into place and expose it, and that is exactly what I did. The piece is called Wishing Wind, and what I noticed in that picture is the cracks – they showed up as stitches and fractures in the surface of the paper. Because of that experience, I started crushing the paper, eventually lying on it in the landscape and meditating. It is upside down, so the surface is touching the ground or the snow, depending on the season, and whilst I’m there I get all of my senses in tune to the landscape, to the night, so that I can see better, so that I can hear better, so I can lose myself in the landscape where I’m at.

MF: Once I got off these large sheets (about 144cm by 244cm) of paper I would crush them into my abdomen, into big balls of paper and it takes energy to do that. I know where I’m going to put that piece of paper, whether it’s in a stream, over rocks, I have an idea of what I’m going to do. I have an idea of what I want. I don’t know exactly how it’s going to turn out. I’m recording that accident and I’m asking the elements and the energies that are out in nature to collaborate with me in a certain sense. I unroll that piece of paper in the landscape. If you were to take a piece of paper at your desk and crush it into a ball and then open it up, you can see all the ridges in it. If you light that piece of paper at an angle, then obviously the ridges that are in the light will be exposed, will become darker, and the backside of that ridge will become less exposed. That is part of my process. I’m celebrating the materials. The same thing is happening in a certain sense to my negatives, where I am basically deconstructing the materials to make something. I’m pushing the materials to the very edge of their being, so to speak, of their existence.

LJ: Any other surprises?

MF: A lot of my pictures are made horizontally, and so, at some point, I thought, why don’t I try to make pictures with the photographic paper vertical in the landscape. There are one or two examples in the book, the Water World pictures, in which I decided to put photographic paper vertically into a lake, at night. I had wrapped my flash in a small Ziploc bag, and I jumped into the lake and dove underneath the paper, under the water, and I flashed the piece of paper from in the lake, and of course, I’m thrashing about, and the water is moving, so the light of the flash is refracting off the water and the movement. I have got some great interesting surprises from that process. Also, all water in nature is acidic from pollution, and I don’t know if you have noticed this in your work, but water bleaches photographic paper and it bleaches film and does all kinds of things. If you were to leave those photographic materials wet for a couple of days, your images will disappear. I use the water like paint and so that by flicking drips of water or wet snow onto the paper and then letting it run, it makes marks. It makes dripping marks that translate in terms of black-and-white into a lighter colour. If you look carefully in a couple of examples in the book, you can see that, you can see these drippy lines in some of the pictures, and that is created by using the acidity of the water, the polluted water, and it is increasing over the years, I’ve noticed, the planet isn’t getting any cleaner. It doesn’t hurt us if we walk through rain or go in the lake or swimming, but it affects our materials. I use that for certain visual effects now.

LJ: It is quite serendipitous, really, isn’t it, nature sort of giving you something.

MF: Sure, I think part of a creative process, no matter what we do, you know, you’re playing piano or whatever, painting, sometimes a splash of red drips onto your white surface and you kind of have this, ‘Oh, the red looks so beautiful there’ and so you put more of them. What I tell young artists and myself, but you know, it’s inherent in me at this point, is that when the going gets difficult in your process, don’t abandon it. Keep pushing through. If you’re making something, and you think, that’s not good. I suggest you just keep going forward. Even though you think it’s not going to be a successful image, go ahead, because that accident, that screw up, as we say, that you have, that you’ve seen, might result in something that you’ve never seen and that’s stimulates you to have your ‘a ha’ moment and push you further in your creative process. You must have faith in yourself and in your process.

LJ: Thinking about working without a camera, how do you think the materiality of your process affects the final image compared to traditional photography?

MF: It took me many decades of working with film and photographic paper to understand how they react to light and chemistry. I followed the rules about handling those materials. I saw, through pushing the processes, how the materials reacted to my handling. Overtime I developed a more intimate relationship to my films and papers by my hands on manipulations. It’s like touching the cloth as some say, I want my energy to also be part of the picture making process. The differences are profound, my photograms and films are near physical collapse, just on the edge of disintegration because of my presence in making a photograph. Direct contact of the materials with me and the natural elements is how I make pictures.

LJ: Nature plays a big part in your work, therefore do you see yourself as a co-creator or more of facilitator?

MF: I think a little bit of both. I liken my photographic paper, these big white sheets of paper that I roll out into the landscape, like a tablecloth, like I am making dinner for 12. I tell this story, where let’s say it’s holiday time and I’m going to make a big dinner. But I haven’t invited anybody. I do the whole thing, I set the table up, I’ve got dinner for 12, cooking, and, and then the phone rings and somebody says, ‘Hey, it’s George, it’s Sally, what are you doing? ‘Oh’, I said, ‘I’m just making dinner’. ‘Oh, we’re coming over then’, and suddenly, you’ve got something cooking, and so I liken this to me being in the landscape. Having an idea of what I’m up to because I must prepare myself physically and the materials, whether I’m going in water, snow or river, lake, or fireflies, whatever natural elements I’m chasing. Then I’m asking those energies and those natural elements to make pictures with me. It’s a little bit of both in that regard. I’m calling on the ‘Hocus Pocus’ world, the invisible world to be there with me, and things happen and I’m recording the event. It’s like on a white piece of paper, in a landscape of snow, in the darkness of night, I’m putting some snowflakes on the paper, but I don’t know where each snowflake goes in the dark, but I have an idea. I know what I’m looking for. Sometimes I see once the flash goes off, because I’m looking at the paper, when I’m doing that, I can almost see the picture, generally, not the minute details -that always happens in the dark.

LJ: Some of my work has been inspired and influenced by the way you are collaborating with nature. Are there any writers, or thinkers, or artists that have influenced your work with nature?

MF: I’m mostly influenced by painters at this point, by the abstractionists. People like Yves Klein, a French conceptual painter. The Italian, Alberto Burri. Painters like Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler and Jackson Pollock. Photographers, not so much at this point. The great sculptors are of interest to me. The poets, musicians….

LJ: You have mentioned some of the images in your book Photograms and Photographs 2020-1970, and I want to talk more about this. I feel privileged to have a copy and find it fascinating. It is interesting that you have presented the work in reverse, having your more recent work first, what is your reasoning behind this?

MF: The camera-less work is what people attribute to me. The photograms are what people know so they come first. The earlier work, the photographs, exist, it is part of my journey, it is part of me and I’m proud of it, so it is in the book.

LJ: The book features a mix of black-and-white photographs and photograms, but there are also a few instances where you have experimented with colour. I’m curious – do you enjoy working with colour, or do you find yourself more drawn to black-and-white?

MF: Well, I like making things, so let’s just start there. I am really happy when I go into the darkroom, and I have been doing that for almost 60 years. I have experimented with colour over the years, even as a street photographer, but I don’t process the colour film and I can’t make the print, and I was never really motivated to do that or get that kind of equipment in my darkroom. I was always at the mercy of the colour lab technicians, and I was never satisfied finding the type of work that would come out of that. The firefly pictures that are just green and yellow in the book, that’s original colour from putting a colour 8 by 10 film through the scanner. In the early days, I didn’t like the quality of the scans. It was technically very difficult for the machines to translate, there was a lot of what we call banding. But I did produce some pictures in 2001 and then I left it alone for a while. Then here in Quebec, north of Montreal, I was driving home one night with my wife, and we saw the fireflies out in the field, and I thought, maybe I should try to make colour firefly photograms. That’s another thing, I don’t like to repeat myself. I like to move on to something else, move the process along. I did start making colour firefly pictures, of which now I have many, and started pushing that process by adding flashes of coloured lights and other approaches to my mark making . So instead of having green and yellow, I’d have a blueish red, and I started messing around as I was making the pictures by exposing the film to little bursts of colour light at the same time, and I really like those results. Some of my recent black-and-white work that you can see out of the Montauk series, you’ll see a gold picture and, maybe reddish and blue. Those colours, they’re being enhanced in the computer, but they exist in the black-and-white film because of the reaction to chemicals and the oxidation, letting the negatives cook and dry with the sand and the salt water and all the other debris that basically gets on these films. In the black-and-white, I’m getting colour, that is being translated through the scanning process. I have found that people are attracted to colour pictures. Black and white is a mental game and colours are a visceral game. A lot of people don’t want to work too hard at looking at things and part of my job, in my mind, is to make it difficult for you to see things. It’s a visual game for me.

LJ: It is interesting that you consider black-and- white a mental game, as Vilem Flusser in his writing ‘Towards a Philosophy of Photography’, believes that black-and-white are concepts and can never exist in the world, but they reveal the actual significance of the photograph. I too tend to work with black-and- white film but find that nature often provides colour to those images in mysterious ways.

You have already inspired me and many others with your work, so my final question is what advice would you give to artists, especially those starting out, looking to work more responsibly or collaboratively with the natural world?

MF: I always mention that one needs to have faith in their process and to not give up when the art making goes sideways. Push ahead with what you are doing, something will reveal itself to you. Be honest and try to be a better person, you will make better art….

Linda Jarrett is a photographic artist, with a long-standing engagement in experimental photography. Her current practice explores the concept of destruction – both literal and metaphorical – to raise awareness of local ecological concerns. Working primarily with analogue and alternative photographic processes, she collaborates with natural elements such as the environment and the sun. She held her debut solo exhibition in 2018 as part of the Core Exhibitions of the Auckland Festival of Photography and her work has received national and international recognition. She holds a BA (Hons) in Photography (First Class) and is currently pursuing an MA in Photography.

Instagram: @lindajarrettphotography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025