Photographers on Photographers: Natalie Arrué in Conversation with Genesis Báez

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Natalie Arrué and Genesis Báez are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

I first came across Genesis Báez’s work while I was in undergrad, and it immediately stuck with me. Her photographs helped me understand what it means and looks to live a diasporic life in a way no other artist had spoken to me. They felt like images of thoughts I hadn’t yet figured out how to express myself. The way she sees and talks about identity, memory, and place is something I’ve looked up to for years. I actually tried to connect with her around the time her first book came out in New York, but it didn’t work out then. So when the opportunity came to have this conversation, I knew I had to reach out. Although we live in different cities, we met over Zoom, and from the moment the call began, the distance between us seemed to disappear.

Genesis Báez (she/her) is a Brooklyn-based artist working in photography. Her practice merges performance, observation, and social histories of modern colonization in a conversation around placemaking. Emphasizing the material qualities of photography, such as light, stasis, and the frame, her work reveals the interconnections shaping our personal and collective lives. Her monograph Blue Sun (Capricious Publishing, 2025) weaves together photographs made in Puerto Rico and its diaspora. Báez’s work is held in the permanent collections of MoMA, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the Yale University Art Gallery, and has recently been shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art and Kilometro in San Juan. Raised in New England and Puerto Rico, she holds an MFA from the Yale School of Art, is a Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture alumni, and a 2025 Anschutz Distinguished Fellow at Princeton University.

Instagram: @genesis__baez

Natalie Arrué: I’m so happy I have the opportunity to talk to you today. I want to hear about you and where you’re at currently, not just to help you out, but also anyone else who could be in a similar position. What’s your origin story, and how has photography managed to weave its way into your life?

Genesis Báez: I think a meaningful relationship with photography for me began when I was a teenager. Before that, I’ve always been interested in art and expression. I used to draw a lot. I was always making images with whatever materials I could find. That’s been a constant throughout my life.

But as a teen I began photographing during trips to Puerto Rico. My family is Puerto Rican. I was born in Massachusetts and moved back and forth between the two places throughout my life. That’s common for many Puerto Rican people, part of a very complicated American citizenship. So there’s this constant movement and fluidity between the two places.

Photography helped me make sense of that. I’d photograph the things I loved, mostly because I wanted to remember them. It felt like this was a place I had to leave or we had to leave and couldn’t remain in. So it started from there.

At the same time, I was interested in photographs as objects. One of my favorite things was my mom’s photo box, the one she brought with her from Puerto Rico when she moved to the U.S. I would constantly go through it—again and again over time. That’s amazing to think about now that everything’s digital. These were physical photos that would get shuffled and reshuffled, so the sequences were always changing. I loved them. I loved the way they looked. I loved peering into a version of history. I loved being able to make up stories about my origin through them.

From the beginning, that was kind of the common denominator: photography as a way to understand where I came from and to orient myself in relation to place, in the movement of a diasporic existence as well as the disorientation and violence inherent to colonization. We were in this liminal space. The photos helped me make sense of that.

I took photography classes in high school, black and white darkroom classes on the weekends, around 2005. At the time I was especially drawn to documentary work, and photography made with the intention of creating social change, such as early 20th-century documentary work from the US. Photographers like Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, Jack Delano, Walker Evans, people who revealed injustice or reflected the world back to itself, as a way to create change or stir empathy and compassion.

That really resonated with me when I was young. I was, first and foremost, interested in the social, in people. As a young person I wanted to make a difference with photography. But now my expectations of it, what I think it’s capable of, have evolved. I’m just as excited by the medium, if not more, but more so in its ability to present questions, and contain and generate subjectivity.

NA: I have the same exact box I go to that my mother did. You get to look at other people’s lives besides your own, and work on yourself through theirs. I also find that in your photography, it’s like a stop in time, but also a document of land and place. It was really interesting to me to see how you infused photographic materials with actual physical material. How did you come to that creatively? Specifically, I think there were some in your book where… which one was it? I think you buried the film in the land?

GB: Oh my god, I was angry. I was really frustrated. I was 22. I had just finished college and was in Puerto Rico with a 4×5 camera, making these beautiful landscapes of the mountains in my family’s hometown. But when I looked at them, I was so disappointed.

I thought, “What a beautiful image of a mountain, this has nothing to do with how I feel about that mountain.” There was such a disconnect between the image and my feelings.

Still, pointing the camera at the mountain told me that land and place were important to me, something I wanted to explore, but I didn’t yet understand how. Honestly, I’m still working through that same question. I was writing a residency proposal yesterday, and it’s literally still the same question, 15 years later.

So back then, I thought, “Okay, clearly I’m drawn to this image of land, I’ve spent all this time making it but what can I do to reflect how I actually feel in relation to it?” Mostly out of frustration I just put the negatives in the ground. I buried them where I had made the photographs. Then I left. I made a little map to track where I had buried them, and when I came back and dug them up, the negatives were totally transformed.

That series is really early work, made between 2012 and 2015, right after undergrad. I was exploring the limits and potential of photographic material.

NA: I love what you said about frustration and disconnect, because I think, as generations keep going, that disconnect just keeps getting bigger. To me, visually, that’s symbolic of a mountain. It’s beautiful, but it also feels physically heavy. A weight.

GB: Yeah, yeah, totally.

NA: Have you seen a common thread in your work? Did you ever think about making work about something else, or has your heart just always come back to that?

GB: Oh my god, story of my life, yeah, for sure. I’ve definitely gone on a lot of tangents, but the work that has ended up being the most meaningful to me up until now ties back to that place, even if indirectly. I think the more specific and personal we are, the more universal something can become. That’s not the only shape art can take, but it’s what has resonated for me.

NA: How often do you visit Puerto Rico?

GB: It really varies, anywhere between once and three times a year. When the pandemic hit, I didn’t go for like two and a half years. But I actually want to say, most of my work isn’t made there.

NA: Yeah, I noticed that. And what’s interesting is that you wouldn’t necessarily know. Like, you’ve made this world where there’s a presence, a piece of us here, that feels really beautiful.

More specifically, in terms of the matriarchs in your family, did you think about collaborating with them in that way, or was that just how your family always was, and you found power in that organically?

GB: That’s a great question. I think when I’m making work, I don’t know what it means. It’s mostly intuitive at first.

I started photographing my mom back in college, between 2010 and 2012, when I was a student at MassArt. I was very interested in portraiture, and she was excited to make pictures with me. So I photographed her in Attleboro, Massachusetts, where I grew up and where she was living and working at the time.

I think before I even had language or clear ideas about what I was doing or why I was drawn to something, it was just rooted in love, you know?

Then I started making photographs in Puerto Rico. And when I was in grad school—sorry, I’m going on a bit of a tangent, but I’ll come back—when I was in grad school and the hurricanes hit in 2017, it completely transformed Puerto Rico. That moment made me reflect more deeply on the systemic displacement of people. Whether due to corruption, economic insecurity, climate change and other manifestations of colonization, all these factors have forced so many Puerto Ricans to migrate to the U.S. mainland.

That’s when I began to want, and need, to create my own visual language for that experience. But I wasn’t really interested in making images that just show what Puerto Rico looks like. I mean, photos are great at describing surfaces and you can Google “Puerto Rican mountains” and get that instantly. I didn’t want to do that.

It goes back to what we talked about earlier with landscape photography, I wanted to bury the obvious, so to speak. I wanted to describe something else. Something more liminal, perhaps the inability to root, why that is, and what keeps us connected instead, that’s where I rooted my inquiry.

It also became clear to me that I wanted to center women in the work. Because it’s through women that I feel the deepest connection to Puerto Rico and to its history. My mom took me there when I was little. The women in my life are the ones who helped me maintain a connection to that place and its history.

And for a lot of my life, especially living in the US, I hadn’t seen images of Puerto Rican women outside of music videos or in the news, and it’s always about some crisis. When have you seen a photo of a Puerto Rican woman just being?

NA: Right, just existing with a sense of normalcy.

GB: Exactly. A sense of normalcy and the mundane.

But again, that awareness came later. At the time, I didn’t know what I was doing, I just wanted to be around my mom. I wanted to be around other women who shared this experience. I didn’t know what it meant, I followed my intuition.

Then, when I started making the book and laid out all the images, I realized—these are the protagonists of this world I’m building. These women are the heart of the narrative I’m forming through these photographs. And eventually, through the publication too

NA: That was going to be my next question. What did you learn after all of this was made? I know I may have asked a version of this before, but there’s this common thread in the work that was so invisible yet present.

GB: Yeah, it just fits together. I would’ve never known that, even as the person who made it, until later.

NA: Oh, that’s so interesting.

GB: I learned that time is such an important ingredient. So many of the photos in the book, I couldn’t really see them when I first made them. I overlooked a lot. Many were excavated from my archive. And it wasn’t until I had distance from what I initially intended, that I could actually see the photographs for what they were, rather than not exactly matching my original intention.

Over time, the images began to take on new meanings. I also learned a lot about sequencing. Images change so much depending on their context, their scale, their position. I knew photos were malleable, but this really reinforced that.

The biggest lesson was not to disregard things just because they don’t resonate immediately. Sometimes a photo or a sketch needs time. That realization has made me feel healthier in my creative process. In the past, I was really fearful of making something that didn’t “make sense” or that was “bad.” What does that even mean! That fear would paralyze me.

Now, I feel like the book reminded me to just make. Stop trying to make sense. Just make and live with the work. Over time, it’ll reveal itself. That might sound passive, but I needed that. I was being so self-restrictive by trying to overdetermine the pictures before they were even made.

NA: Almost like a paralysis. You don’t even know how to move. You think, “No, it’s not going to come out right,” and that thought becomes its own reality.

GB: Totally.

NA: I was also curious, when you were in academic settings, do you think that influenced how you interpreted your own art?

GB: That’s a good question. I don’t know exactly. I think the pressure I felt was mostly self-imposed but definitely shaped by the structure of academia. There were constant deadlines, constant critique. It was scary to put up pictures I didn’t understand, or like. I really cared and wanted to make the most of it, but that urgency, which can be really helpful in getting us going and helping us not overdetermine something, kind of turned on itself and I became afraid of not knowing what the work was about, of being in the unknown of creative process, and sharing that vulnerability in front of people. That fear turned into this weird self-censorship.

My professors encouraged me to put up everything, we learn from it all. It takes time to get comfortable with that. Teaching has further reinforced that. I learn from my students as they learn from their mistakes and process. I’m sure I’ll keep uncovering more, like peeling an onion over the years.

NA: That’s really insightful. I think a lot of students need to hear that. I know a lot of the work in the book is from earlier years, but what are you working on now? Are you continuing those ideas or exploring something new?

GB: Some of the work in the book is older, but most is from the last couple of years. I’m using the book now almost as a compass. Certain pictures in it feel like new directions.

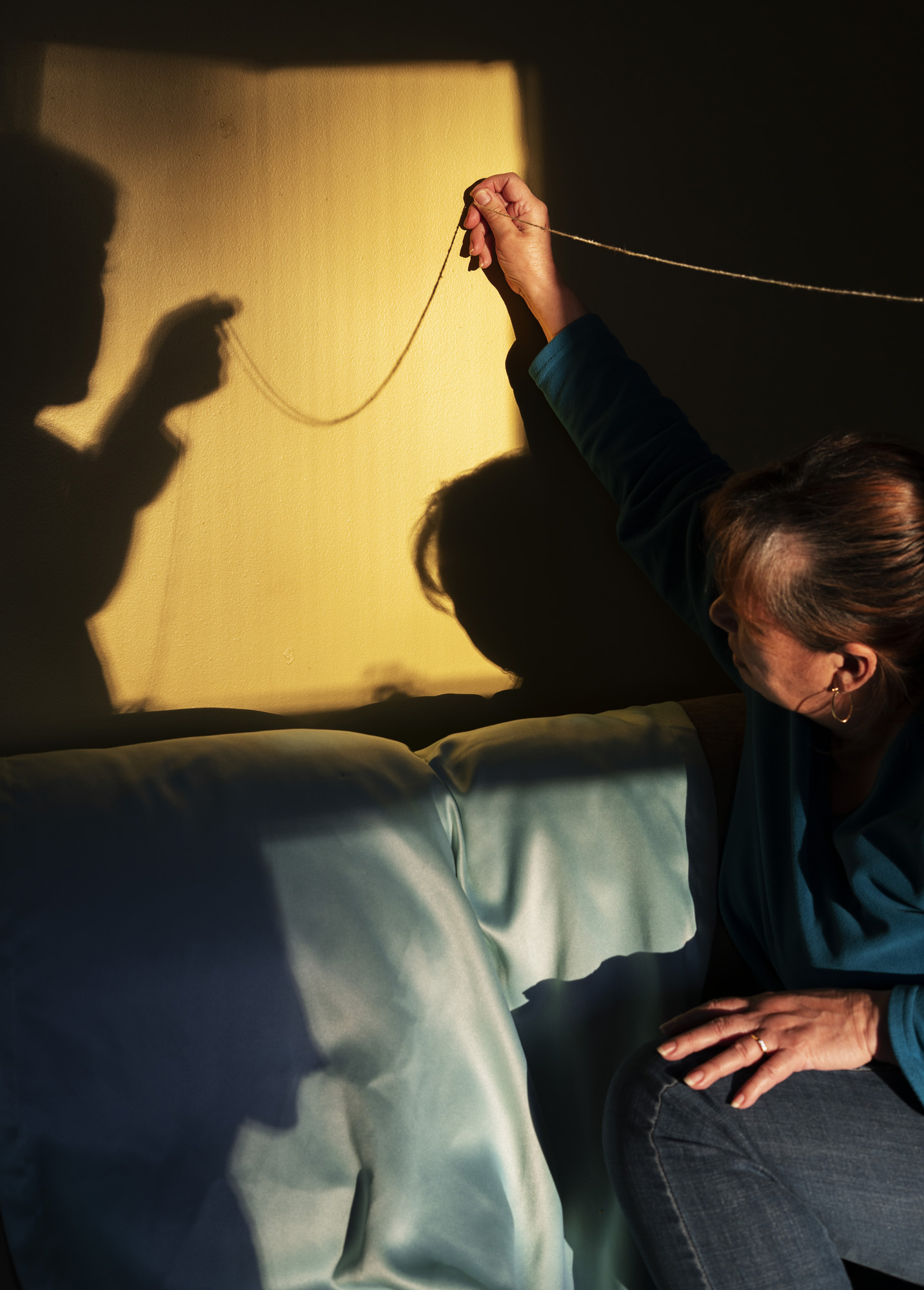

Báez turns the phone camera towards prints hung in her studio.

Here, I’m glad I’m in my studio. I’ve been thinking a lot about this picture. It has this kind of celestial, constellation thing happening. It’s me and my mom, holding a string. It’s a long exposure, so the stars show up and we’re blurred.

Another one I’ve been thinking about is this image without a person — it’s sand and water forming what looks like a figure, like a snow angel. I feel a presence in it.

Báez points to another image, carrying the phone to show me.

And then there’s this one, also me, holding two mirrors, reflecting the sky. You see my legs, my shadow, the cracked mud, it forms a kind of portal.

So right now, I’m building off a few images and exploring a lot of the same ideas: connection to land, place, the biosphere. What can photography show us about these relationships that we can’t just see with our eyes? I’ve been in the woods a lot, by myself, just observing, instead of asking people to make something with me. It’s more solitary now.

NA: That introspection, not having to rely on anyone else. It’s a kind of freedom. That image with the mirror, didn’t you make something similar with objects? What did you call them?

GB: Yeah, water objects for thinking. Want to see them? They’re in here.

NA: Whoa! Wow. That’s so sick. Oh my god.

GB: I love that you’re into it. I collected all of these things from the ground — shards, bottles full of earth. I just keep them around.

NA: They’re amazing, thanks for showing me!

GB: Of course. I still wonder if I’ll ever make something I’m excited about using them. I made a video once, during grad school, where I asked people to hold one and imagine its origin, based on touch, texture, color. The video’s not quite where I want it formally, but it helped me understand the role of sensorial memory in my work.

I keep those objects in the studio, and while I don’t photograph them directly, they seep into my imagination. They influence how I see.

NA: Yeah, when we’re around things, they start to connect to other ideas.

GB: Yes! For example, this photo of mirror shards in the snow.

Báez shows me an image on her studio wall.

They’re broken and blue, they remind me of the objects. Fragmentation, reflection, the sky. Same with this one, this blue just lived in my subconscious until it emerged in an image.

NA: Right. Knowledge isn’t always logical. The subconscious plays a big role in how we move through the world.

GB: Exactly.

NA: The title of your book is Blue Sun. There’s so much blue in your work, is that connected to water? Or something else? Blue is such a layered color that can reflect sadness, serenity…

GB: I always imagined if all of this were a sculpture, it would be a blue ball or a sphere, like Neptune, or a marble. That’s what the feeling looks like to me.

The blue circle can be the movement of my body across the ocean, the sky, from the States to Puerto Rico and back. That’s the shape of my movement.

I think of blue because of the water in my work but also, the water isn’t blue. It looks blue because of the sky. There’s that mirroring.

Blue Sun as a title also describes the materials I’m working with most in these pictures, water, light. Later, I read about how in the atmosphere, under certain conditions like volcanic eruptions or pollution, the sun can appear blue. That deepened the meaning. Earth in the sky.

The title came after lots of lists and back-and-forth, like naming a baby. My editor also really encouraged Blue Sun because it’s also an image. You can visualize it.

NA: I love that it’s in both Spanish and English.

GB: Yeah and the cool thing is, if you fold the words in half. “Blue” aligns with “azul,” and “sun” with “sol.” They’re mirror images, but not literal translations side by side. Only when mirrored do they match. You can’t make that up.

NA: Wow, I’m literally folding it in my head right now. How was it connecting with people at your book opening?

GB: It was really nice. I was reminded of how art brings people together, how it’s helped me build my community. So many of these pictures sat on my hard drive for years, no one saw them, not even me. So to finally be able to share them? And connect with people through them? That’s what it’s about.

NA: What creative thought or question has lingered with you over the past year?

GB: Great question. I’ve been thinking a lot about how photography or working with a camera can be a tool for developing sensitivity and staying present. There’s so much speed in the way we consume photographs now, especially through social media. I often find myself looking at photos to disassociate, to scroll and zone out. So making this book reminded me that photography can also do the opposite. It can facilitate a type of presence and deep attention with the world and with ourselves. That realization has guided me creatively.

I’ve been working more with film, especially in the darkroom—color photogram experiments, because it slows me down. Even when I use digital, I try to use the camera as slowly as possible.

NA: Yes! Photobooks really bring you back into a slower, more intimate experience with images. We can’t lose books, they’re necessary.

GB: I’m trying to bring that same sense of intention and slowness into my process when making photographs.

NA: What’s nourishing you right now?

GB: There’s a river near my studio called the Green River, it’s been keeping me sane. It’s been one of the few things that makes sense to me during this time of pain and rage, of witnessing a genocide live-streamed. And the silence around it. That has forever changed me, and my relationship to the camera in a way I don’t totally understand yet. I keep going back to the river.

Also, staying connected to my friends. I recoil when I’m tired and depressed, naturally, but staying connected to community is healthy and necessary. Most of all, remaining in relation to creation, not just through photography, but through anything! Cooking, mending clothes, learning music. Creating in whatever form.

NA: That’s so healthy and shows how much you’re growing. And that makes me really happy. Sorry, I think I cut you off there.

GB: I was just saying that it makes me happy too, to remember that creativity doesn’t have to be confined to photography. We can channel that energy in different ways.

NA: Absolutely.

GB: Creativity is innate. We all have it. The more I nourish that energy, no matter the outlet, the more in touch I feel with myself and the more available I am to others, and to make photographs that meet the world.

NA: Your words are so poetic. Is there anything you want to share with someone who’s struggling to think creatively or listen to their voice?

GB: Definitely. You don’t need to have an artist statement to go make something. Being led by intuition, curiosity, and love is valid. Those are real ingredients in the creative process. Language and analysis are part of it too, but they can come later.

Making can be a way of thinking through feeling. We can feel our way forward. It’s okay not to have it all figured out, you just keep going. The act of creating leads to more clarity.

NA: That’s such good advice, I’m already thinking about how to apply that.

GB: Yes! Sometimes it helps to choose a few grounding parameters like, “I’m working in the woods,” or “I’m working with black-and-white film,” or “I’m photographing my sister.” That gives you a place to start. Then you make something, pause, reflect, and keep going. The process can guide you. The next step will reveal itself. Easier said than done though!

All of my favorite photos came from that kind of process. I had no idea what they were going to be. The camera transforms the world.

NA: You never know what to expect going into it.

GB: Right! Take this picture: this was made with a timer. I wasn’t behind the camera. My shadow is holding a string, and I would have been just outside the frame. The light was changing so fast. I ripped the curtain off the window to create this waterfall effect on the sofa. I had maybe two minutes before the sun dipped behind the building. One of those minutes was used up by plugging my dead battery into the charger to get back up to 2%. My mom held the string, and I just hit the shutter release.

You build a vocabulary over time. Like I had been working with string for a while, so it was already “in my pocket,” so to speak. Then, when you only have two minutes, you pull it out, and maybe it turns into something.

NA: I love that story, it really resonated with me. I’ve had those same moments of everything coming together by chance.

GB: Chance is essential to photography. Whether you’re photographing in public spaces or in a staged environment, it’s part of what keeps photography exciting and magical to me.

NA: Thank you so much. I really appreciate this conversation!

Natalie Arrué (b. 2001) is a photographer based in Metro-Atlanta, Georgia. Her work reflects on identity, memory, and place through the lens of her Salvadoran heritage and personal upbringing. As a first-generation Salvadoran American, she collaborates with her family and their photo archive, weaving together generational narratives, religious symbolism, and staged rituals to explore the tension between inheritance and self-definition. Natalie earned her BFA in Photography from the Ernest G. Welch School of Art & Design at Georgia State University. Her work has been exhibited Eyes on Atlanta: Contemporary Latinx Photography at the Atlanta Photography Group Gallery and The Curated Fridge in Boston. She is a 2025 John Perrin Award recipient and a Lenscratch 2024 Student Prize Honorable Mention and “Top 25 to Watch.” Her work has been published in La Horchata Zine, New South: Reciprocity, and The Underground Journal.

Instagram: @photogrphic

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

The Aline Smithson Next Generation Award: Emilene OrozcoNovember 21st, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025