Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas Muellner

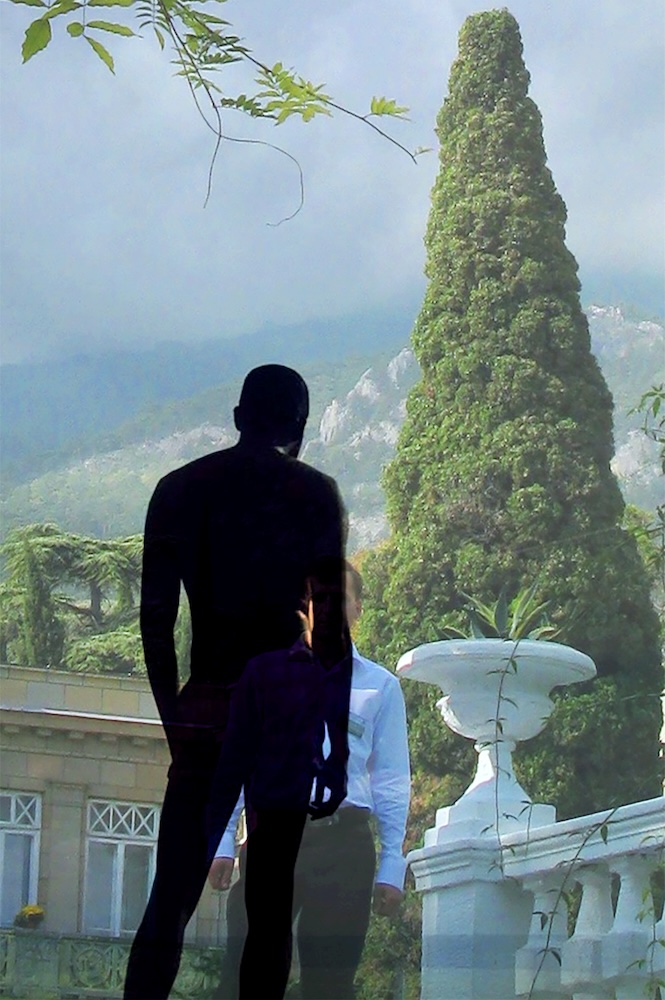

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas Muellner are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

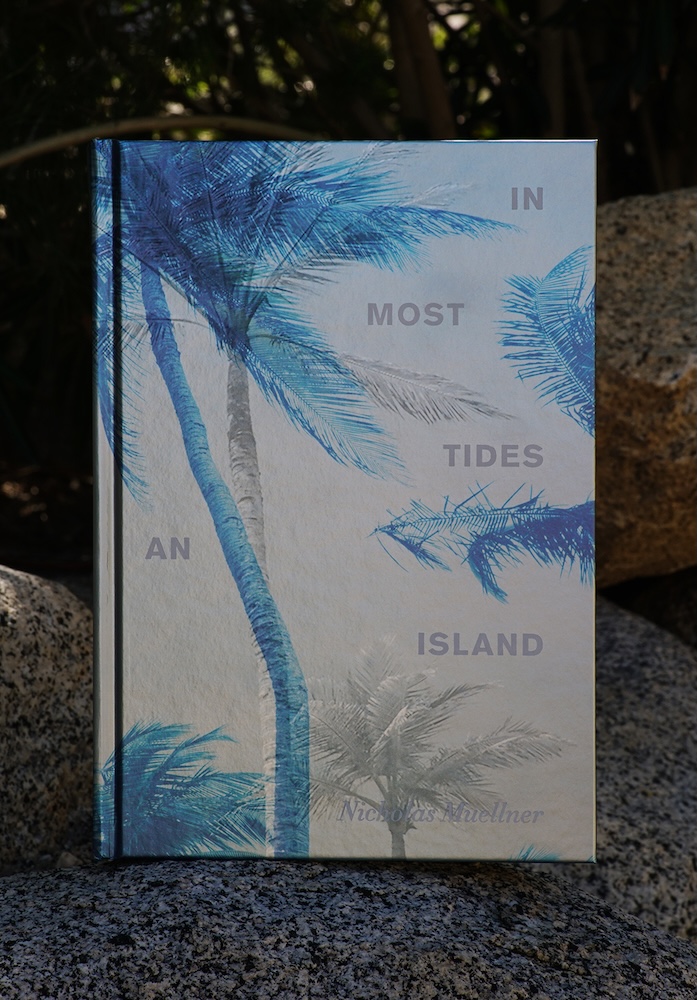

There are certain photo books that have played a pivotal part in shaping my work—Nicholas Muellner’s In Most Tides an Island is one of them. This fever dream of a book—my entry point to Muellner’s photography and writing—brings the reader on a journey across continents, weaving together seemingly disparate narratives into a shared story about loneliness and connection in the internet age. Muellner is not afraid to embrace a variety of visual and literary styles, and this kaleidoscopic approach overturned my expectations of what photography can be. Muellner collapses time and place and alternates narrators, self-reflexively blurring lines of identity. His work has shown me the expansive possibilities of image and text acting in tandem, as well as the potency of photographic metaphor in expressing the fragile, multi-layered nature of memory.

In this conversation, we touch on Muellner’s unique approach to sequencing and editing images, how his early studies in Russian literature shaped his artistic trajectory, and several exciting projects—past, present, and upcoming.

It has been my distinct pleasure to speak with Nicholas about his artistic practice and career. Thank you, Nicholas, for a wonderful conversation, and to Lenscratch for this opportunity. And a special thank you to Matthew Connors for introducing us!

Nicholas Muellner is an artist who operates at the intersection of photography and writing. Through books, exhibitions and slide lectures, his projects investigate the limits of photography as a documentary pursuit and as an interface to literary, political and personal narratives. His five published books include The Photograph Commands Indifference, The Amnesia Pavilions, Lacuna Park: Essays and Adventures in Photography, and In Most Tides, An Island, which was shortlisted for the Aperture/Paris Photo Photobook of the Year. In addition to solo exhibitions in the U.S. and Europe, his writings on photography have been published by MACK, Aperture, Afterimage, Triple Canopy, Art Journal, and Routledge. Muellner has performed slide lectures internationally, including MoMA P.S.1, the Carnegie Museum of Art, The Photographers Gallery, and the Museum of Contemporary Photography. Muellner’s work has been supported by the John Gutmann Fellowship, residencies at the MacDowell and Yaddo Colonies, the Russian National Center of Contemporary Art, and the Carnegie Museum of Art, as well as grants from the Trust for Mutual Understanding and CEC Artslink. He is a 2018 Guggenheim Fellow in Photography. Muellner received a BA in comparative literature from Yale University and an MFA in Photography from Temple University. He is founding Co-Director of the Image Text MFA and ITI Press at Cornell University.

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

Elizabeth Hopkins: We first met a year and a half ago, in Matt Connors’ photo books class at MassArt. It was during that class that I discovered your book, In Most Tides An Island. It was inspiring for me to see how you wove together so many different ways of picture-making and writing into a symbolically cohesive story. Would you speak to how the different threads in the book came together over time, and what moved you to take this approach?

Nicholas Muellner: I make projects at different speeds. Some projects come together because they have a very specific polemical idea, and others evolve over time, as their meaning changes. In Most Tides An Island is the latter. That project started as a series of black and white images—tropical-Gothic landscape photographs—which I made on three trips to a small island off the coast of Nicaragua. The first iteration of the work was an exhibition at a gallery in London, which featured these photographs and one short text piece drawn from a text I had begun to write just before the exhibition, about a fictional woman on that island. I had a reading of that text in the gallery, and that was the very first relationship between the text and the image.

Meanwhile, I had started another project in which I developed online dialogues with closeted gay men in newly Russian-occupied Crimea, and then traveled there twice to meet them.

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

NM: Initially, I thought of that project as separate from the work I’d made on the island. But, as I continued working on it, I realized that the two projects were about the same thing: solitude and self-perception, and how the digital age affects our sense of aloneness and connectedness. And so, from that realization, it evolved into what it became in book form.

Usually, my books develop as slide lectures, and the slide lecture turns into the skeleton of the book. The book I’m finishing right now started as a slide lecture, as a way to figure out the intention and the relationship between language and image. Advancing the slide and speaking aloud is different from reading the text and turning the page, but they’re related. I tend to think of a book as a kind of proto-cinematic experience, and the slideshow exists between a book and a film, in that you’re moving through time in a way that I control. I like giving space to the viewer or reader to move around themselves, which is, in a way, why I don’t make cinema. But I’ve always admired the way that cinema can control and pace your experience. The slide lecture allows me to construct that, but with more space than a film would allow, and the book is a further iteration of that.

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

EH: The relationship between cinema and photography is so interesting—in books and movies, the image lingers in your head, and you’re still holding onto it as you see the next one. But it’s also transient.

Do the slide lectures start as classroom lectures, or are you just making them for yourself?

NM: When I’m invited to give a visiting artist lecture, like the one I did at the Museum of Contemporary Photography or the Photographer’s Gallery in London, that’s where they develop. I want the lectures to be before a public, not just a group of students. With students, I have a different responsibility, which is sometimes to give them a sense of how I work, but it’s mostly about teaching them possibilities and giving them a range of influences, structures and thoughts. I have a different responsibility as a teacher than I do as a performer, so to speak.

EH: That makes sense—it’s about the students, not about trying to work out ideas.

© Nicholas Muellner, In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

EH: Going back to the book, it was exciting to witness the different narrative threads come together. For me, the sequence of ice images later in the book, where you’re writing about this metaphor of a reflective surface hiding what’s underneath, is where it all clicked. I wonder if that’s how you planned to structure the book?

NM: I didn’t think of that as necessarily the moment where it cohered, but it was a kind of “third voice” that entered the story. There is an awareness, which is important to me as a kind of documentary maker, that my relationship to the subject is part of the story, because there’s no neutral objectivity out there. For me, that means acknowledging the expectations you bring to an experience, and how you see yourself as part of the complex of politics, emotions, and anything else you’re talking about. I don’t think that’s an obligation for all artists, but for me, it’s important. It’s a way of acknowledging how I’m filtering information and narrative, and, especially when engaging in metaphor or symbolism based on the lives of people, acknowledging that I’m engaging in that process of transformation.

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

EH: With In Most Tides, but also in your other projects too, such as The Amnesia Pavilions, there’s a strong relationship between psychology and memory. Could you speak to that?

NM: I think ultimately my narratives are emotional narratives first, and I feel like our emotional experience is preconditioned by the past, by memory. Therefore, the relationship between memory and emotional experience is central to me. It’s not the only thing that structures my work, but it’s an important element, especially in projects like The Amnesia Pavilions, where I was dealing with a shift in my self-understanding, but also a shift in a country’s reality and self-understanding—the Soviet Union becoming Russia. In In Most Tides An Island, memory appears, but it’s not a central theme. So, it really depends on the project for me, but memory never fails to interest me, because it’s what we build our perception on, as readers, makers, voters, citizens—as anything. Leaving out memory is often a way of leaving out the story, or the grounding of it. The cliché is that if you don’t know or understand the past, you’re bound to repeat it. I think that’s true of nations, but it’s also true of individuals.

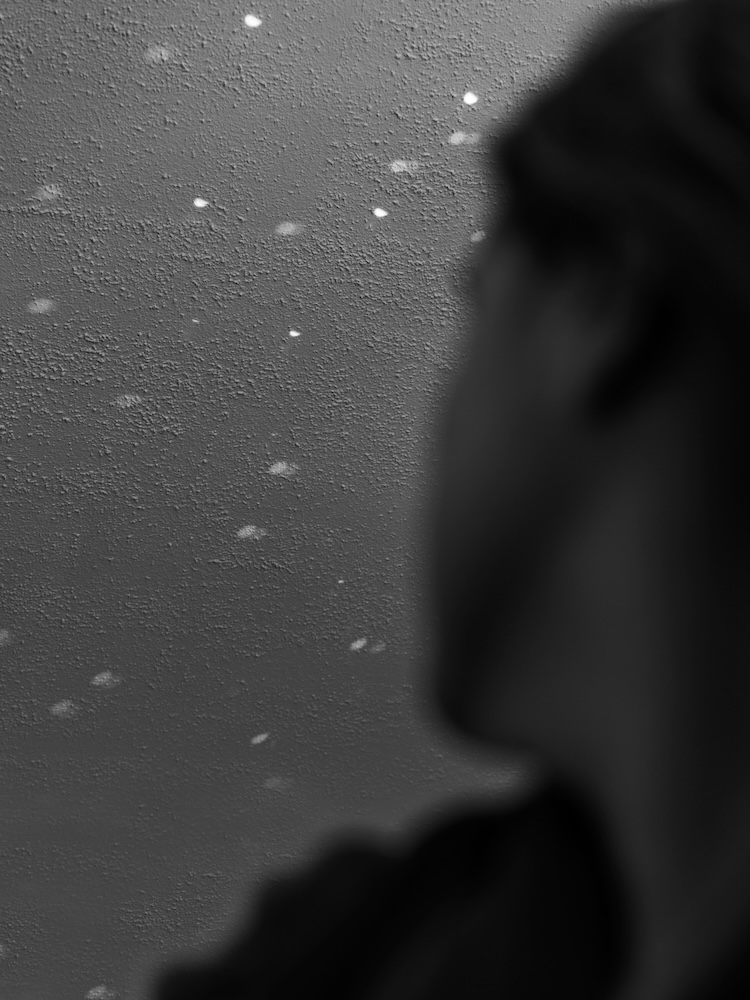

© Nicholas Muellner, from The Amnesia Pavilions, A-Jump Books, 2011

© Nicholas Muellner, from The Amnesia Pavilions, A-Jump Books, 2011

EH: When I was looking through The Amnesia Pavilions, it seemed like the past—the images from the 90s—was very peopled. Meanwhile, the current images were much more barren. I found that so interesting, because it reminded me of how memories can feel like ghosts. You might be in a space, remembering how it used to be, but it’s like your mind is trying to map onto the current space something that’s no longer there.

NM: That’s a good way to put it. I think that was the tension I wanted to create. In the past are all these people I encountered at a certain place in my life, and going back was about a projection into empty space… I no longer had or felt the connections that I previously had, so the memories couldn’t really be placed. We think of our relationship to geography as a stable thing. But if an entire country changes its social landscape, its physical landscape, its architecture, the place is not the same place. How do you locate yourself in a place where you never really were grounded to begin with, and that has so radically transformed?

There’s also a sense of rupture between past and present self, especially in that book, where I’m talking about an experience of a world that no longer exists, but also of an idea of myself as a closeted young man versus a more mature version of myself—they’re not continuous. There’s rupture there. Those empty pictures, the sorrow of those empty pictures, speaks to that rupture.

EH: It’s very moving. I also think a lot about memory in my own work, and why we are so often held by the past. I think there’s this romantic notion about continuity of self, as if you could trace a direct line between the you on the playground and the you now. But the idea of these ruptures that happen throughout your life is actually more accurate. Sometimes, if you go through a profound change—it’s not that you’re totally disconnected from your past self, but there is a feeling of disconnection there.

NM: Disconnection is alienating—there’s a loss, but it also can be a liberation.

© Nicholas Muellner, from The Amnesia Pavilions, A-Jump Books, 2011

EH: A lot of your work is about Russia, but you grew up in the Boston area. What is your connection to Russia?

NM: My primary entry point was Russian literature, which I love, and so I studied Russian language with the desire to read it in the original. As an undergraduate, I was a comparative literature major doing Russian, French and English literature. Even though I knew I wanted to be an artist, I also loved literature and had an opportunity to work with amazing people and learn a lot. Literature was the bait and Russia was the trap.

Part of my family were Jews who came from Russia, but even the ones who were still alive when I was a kid and who had learned Russian before emigrating would never, ever speak it—it wasn’t their language. They had to use Russian, but Yiddish was their language at home, and they also just wanted to forget that part of their lives completely. So, there was that sense of some historical connection in my family, but not a direct one, really.

I visited Russia as a young man in the early ‘90s, at this moment of dramatic change when people were incredibly open. I had the luck of being one of the first Westerners to arrive in some newly-open cities. I was an object of fascination, and I could communicate with people, so I made all these connections because we were all eager to get to know each other. It was a little bit of an historical accident.

After I made those first two trips, I didn’t go back to Russia again for over a decade. By the time I returned, it was a different country. It’s a different country again now. I don’t know if I’ll ever go there again.

EH: How did you come by the opportunity, originally?

NM: I won a student travel grant to photograph along the Trans-Siberian Railroad in 1990, the summer after my junior year of college. It was an incredible privilege. And so, I just went, by myself.

EH: Wow, that must’ve been incredible. You never know where things might lead!

© Nicholas Muellner, from The Amnesia Pavilions, A-Jump Books, 2011

EH: Looking back so far, are there one or two moments that stand out to you as being particularly formative for your work?

NM: Well, that moment I was just talking about, of being in Russia in the early 90s, was certainly formative. I don’t really have a singular moment, though, because it’s such a continuum. I’ve always admired artists who didn’t have one method and subject, even though I respect artists who, you know, make the white painting their whole lives, or find a certain technique that works for them… I just want to discover new ways of expressing things and to talk about different things. And so, even though I come back to certain themes over and over again, like solitude, loss, memory… what I’m working on finishing now is not really about any of those things. It really depends on the project, and I try to shift my perspective.

I stopped writing for a long time. Between 1995 and 2004, I didn’t really write, I just took pictures. During that period, I just wanted to make images that felt like they did something that language could not—that were resolutely silent, and that was their means of expressing themselves. I think I learned a lot about image-making in that time. Returning to writing and having a clear idea of how I wanted to make images allowed me to start integrating those two things. It wasn’t a moment, but a process.

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

NM: Sometimes students come to me, saying, “I have this writing and I have these images, and I want to put it all together!” And sometimes you have to say, “The images are doing something; that’s where the energy is, so why don’t you put the text aside?” Or vice versa. We get attached to things—whether it’s a medium or a project or a kind of image—that don’t necessarily serve us. We get caught up in the problems and possibilities of it. So, sometimes you have to put things aside. Learning that was really useful to me.

EH: That resonates a lot. It’s hard to gain the distance you need from your own work, to have clarity on what it’s actually doing.

NM: I think you get that clarity from time, but also from sharing it with others. One of the reasons I do slide lectures is because when I’m sharing work with a public, I can feel what I don’t like, in a way that I don’t hear or feel when I’m reading it over myself. It’s not just that other people can give you feedback, which is also valuable, but also that you are sensitive to what works for an audience when you have to share it. With books or exhibitions, you’re not always standing there with the person when they’re reading, so having a captive audience where you can feel when the energy is or isn’t there, is a very useful part of the process to me.

© Nicholas Muellner, from In Most Tides an Island, SPBH Editions, 2017

EH: You mentioned a project that you’re working on now—would you be willing to share a bit about it?

NM: I have a few different projects at different stages, but the project I’m finishing now is a book that will be coming out next spring. It’s a book-length essay with images. It’s a polemic and a provocation, a call to try to reimagine how we communicate culturally, not just as artists. The image culture of the present world does not create common languages of understanding, and the book suggests that we need a new allegorical vocabulary, or vocabularies, so we can try to establish new frameworks of common meaning. We’re so fractured. Every niche of recipients has this endless stream of “the real” that is not the same as anyone else’s stream of what I call contemporary realism, and this is inherently disintegrating to common cause and common culture—to any kind of politics of consensus. It’s a very different essay for me. It’s not deeply meditational or personal. It has personal elements, but it’s much more about a cultural condition I’m trying to think through.

EH: That sounds super relevant. I’m looking forward to reading it—I want to get my hands on a copy when it comes out!

Before we go, do you have a piece of advice for rising photographic artists or writers?

NM: It’s hard to generalize that! I think it’s important to be patient and realize that it takes time to develop a voice and to find an audience for what you do and care about, rather than trying to create work you think the audience wants. In the long run, having an original voice that’s authentic to you as an image-maker or writer is the essential thing.

Elizabeth Hopkins (b. 1993) is a photographic artist and educator based in Boston, MA. A lifelong visual artist, Hopkins discovered her passion for photography on a road trip across the Midwest. She is a graduate of Massachusetts College of Art and Design, where she earned her master’s in photography. She holds a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Skidmore College.

Hopkins has shown her work in numerous art galleries, including MassArt x SoWa (Boston, MA), Galatea Fine Art (Boston, MA), The Curated Fridge (Somerville, MA), the Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, MA), and the Rhode Island Center for Photographic Arts (Providence, RI). Her images have appeared in publications such as F-Stop Magazine and Pearl Press. She received second place as an emerging artist in Plymouth Center for the Arts’ 2025 annual photography exhibition.

In her practice, Hopkins explores themes of memory, transience, and the peculiar melancholy of the everyday.

Instagram: @eahopkinsphotography

© Elizabeth Hopkins, Where the Cosmos Is Felt, 2024

© Elizabeth Hopkins, Here, 2023

© Elizabeth Hopkins, Skipping Stones, 2024

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025