Astrophotography: Linda Thomas-Fowler

Linda Thomas-Fowler is a prolific astrophotographer imaging from her home in Virginia and observatories in California and Texas. Her images of galaxies and deep sky objects reveal mysteries unseen with the naked eye.

I am an amateur photographer and an amateur astronomer. I’ve been fortunate to be able to combine those two passions into one but while those are my passions they have not been my career. I am retired but worked for 37 years in the software industry writing software and doing software performance analysis.

Currently, I split my time among two astronomy clubs (the Shenandoah Astronomical Society where I am the current president and the Northern Virginia Astronomy Club) and working with the PFLAG Woodstock Virginia chapter to support and advocate for LGBTQ+ people in our local area.

The Spectrum Podcast: https://spectrumpodcast.org

An interview with the artist follows.

Statement

There are two interests that I’ve had almost as long as I can remember. One is astronomy and the other is photography. In hindsight, it seems inevitable that I would end up combining them but, aside from some eclipse photography in the 1990’s they remained firmly separated until the 2017 total solar eclipse. Photographing that eclipse reignited the desire to take pictures of the night sky. It turned out to be the most difficult photography I’ve ever done but it’s also been the most rewarding! For reasons I don’t really understand, it was a passion and one that I had to follow.

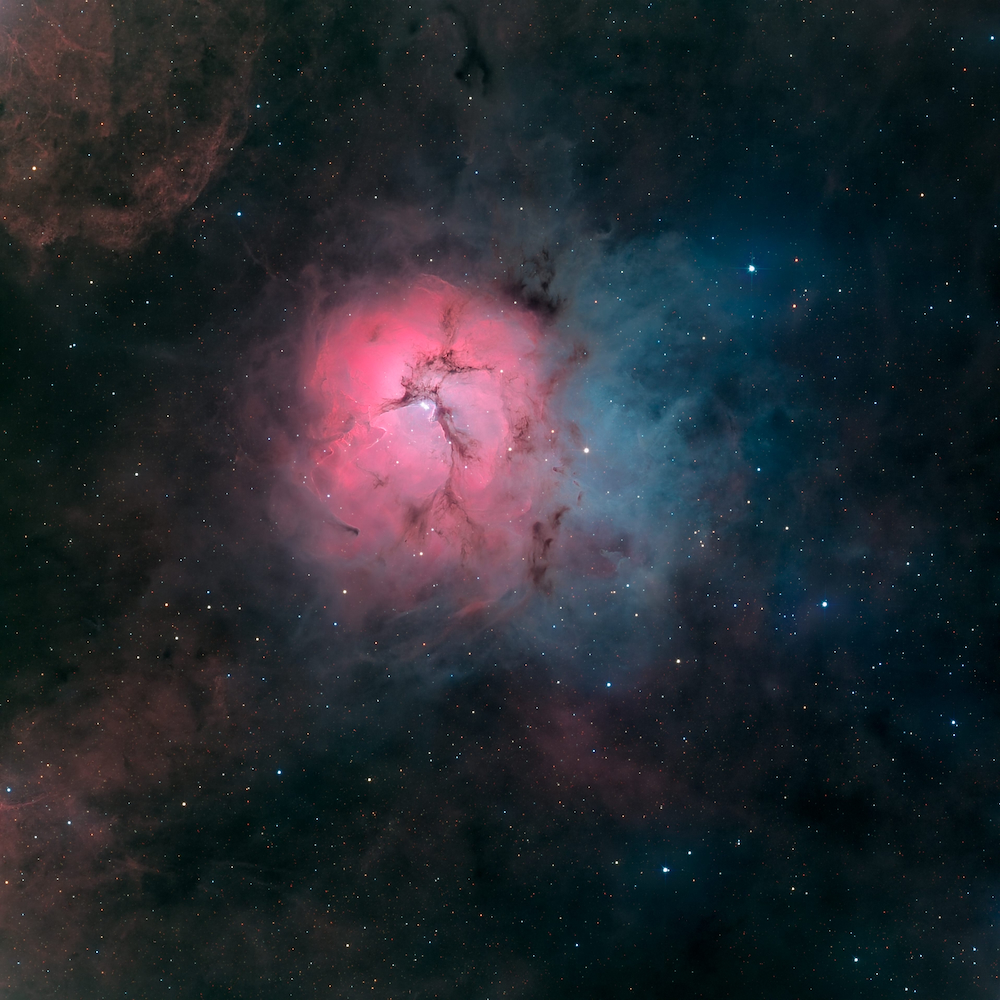

There are many types of astrophotography but the one I’ve been the most drawn to is deep sky astrophotography. These are images of nebulae, galaxies and star clusters. Unlike conventional photography, most deep sky imaging is done with many individual sub-exposures over hours or even days that are later combined in the computer to make the final image. It’s about as far from instant gratification photography as one can get, but it’s also been some of the most rewarding photography I’ve ever done.

For me, it’s been a chance to learn about the technical aspects of imaging and about what’s going on up in the sky. Each image is a chance to learn something about the target, and it lets me see the sky in a way I never could putting my eye to the telescope – if I could even see the object through the telescope.

Whether it is a “nearby” nebula that is 600 light years away or a galaxy that is 40 million light years away or a cluster of galaxies that are 300 million light years away, astrophotography expands my mind and satisfy that insatiable urge to know what is out there.

Astrophotography exercises both halves of my brain. It’s technical and detail oriented but it also gives room for tremendous freedom to interpret the data in processing.

Marsha Wilcox: Tell us about your photographic journey.

Linda Thomas-Fowler: I was an Apollo baby. I was just old enough to remember Apollo 11. I remember my parents letting me stay up to see that. That was it, I was captured by space. I was very interested in astronomy from a very early age. The first thing I ever told my mom I wanted to be was an astronaut.

When I was 12, I was given a hand-me-down Sears refractor telescope. I lived outside of

Baltimore, and I didn’t know what I was doing, but we could see the moon with it. That was about the only thing we could find. I was just amazed at the kind of details that you could see. I had also become very interested in photography. I remember saving money in junior high to buy a 35-millimeter camera. I took pictures of anything that would sit still long enough for me to take a picture. In college, I took an actual photography class which taught me more about composition and things like that.

Later, in the 90s, I got a bonus from work and got myself a real telescope, a Celestron 8-inch. I was living in Virginia and got connected with the Northern Virginia Astronomy Club. They taught me how to use it and how to find things, which was a great deal of fun. I thought, well, at some point I’ll combine photography and astronomy and do some astrophotography. But it was too hard, too complicated. I never really got beyond doing a couple of eclipses.

In the 2000s we had the digital camera revolution, and I got my first digital camera. My

photography improved and I got involved with the local photography group. We would go out shooting things together and we’d compare images when we got back, 80% would be essentially the same, but then there were some in which somebody saw something in a different way. That was eye-opening. It made me see the world in ways that weren’t native to me.

My style then was very much reactive. I tried to branch out into more sedentary kinds of photography like landscape photography. I wasn’t as successful because you have to wait for the moment instead of reacting to the moment. Astrophotography turns out to be much more like landscape photography than people photography, or at least non-portrait people photography.

I combined astronomy and photography in 2017 when we had an eclipse that was visible here in the US. Taking pictures of that reignited the passion for astrophotography. So, I started doing a lot of reading, a lot of video watching and I had gotten reconnected to the local astronomy group. I discovered it was a lot more approachable thanks to digital cameras and computer control of telescopes, but it was still hard.

My first attempts were very painful, and not very successful. It turned out I was fighting equipment problems, but I didn’t know enough to know whether it was me or the equipment. It took months to prove that it was the equipment. I eventually replaced the bad equipment, and it was still hard but approachable.

There are as many kinds of astrophotography as there are regular photography: planets, nightscapes, deep sky astrophotography, and comets, to name a few. What really drew me was deep sky objects, being able to look at things outside our solar system. Things that are anywhere from hundreds to millions of lightyears away – to be able to see them and learn about them.

Can you share your Astrophotography Process?

I discovered with astrophotography you have to plan, you have to decide what you’re going to do. You have to take a lot of things on faith because you can’t always see what the final result is going to look like until you spend hours, or even days, collecting all that data. Sometimes it was successful, sometimes not so much, but I learned a lot from all the failures.

Note: Astrophotographers combine many images to make the final finished image. The interim images are often referred to as, “data.”

I don’t really think of myself as an artist – I think I’m kind of like a mid-way point between art and science, I’m not really doing science I’m not really doing art. It’s fantastic that other people like looking at my images.

Can you share about the observatories from which you photograph?

Thankfully, someone reached out to me when he learned I was thinking about building an observatory and offered me access to his observatory in West Virginia. I was able to use his equipment. It was a quality I’d never be able to own. It took my astrophotography to another level. He connected me with somebody who had a telescope in a remote observatory in California who was looking for a team. I became part of that team. That was also equipment I’d never be able to own – and I had access to clear skies that happen way more frequently than here in Virginia. If we get one good imaging night a month that’s good.

Although I live in in darker sky area now, it’s still not as dark as the place in California. I also became involved in a remote observatory in Texas. Between those two, I was able to collect a lot of images and learn a lot about image processing. It also gave me a chance to not just take a picture of something, but also to go learn about what these things were. For example, what was going on inside these little towers of dust, and what was going on with this glowing gas, and how far these galaxies were away, and that sort of thing. It’s been a great way to learn about what’s going on up in the sky. Being able to combine photography and my own education has kept me motivated to take the next picture.

There is art and science in astrophotography. What do you think?

One of the questions I get asked about most images is, ”Is that real?” The answer to that is, well, no photography is truly real.

There is often a discussion about how we manipulate the data to show what we’re interested in. If we’re doing a broadband image, something done with either a color camera, or using red, green, and blue color filters on a monochrome camera, those colors are approximating real life. However, we have to do things that a terrestrial camera would do for us. Color balancing, for example. We can’t just set the camera to a 5,600 Kelvin daylight setting and there we go. We have to do that on our own. You can choose color balance in different ways depending on what you’re trying to emphasize.

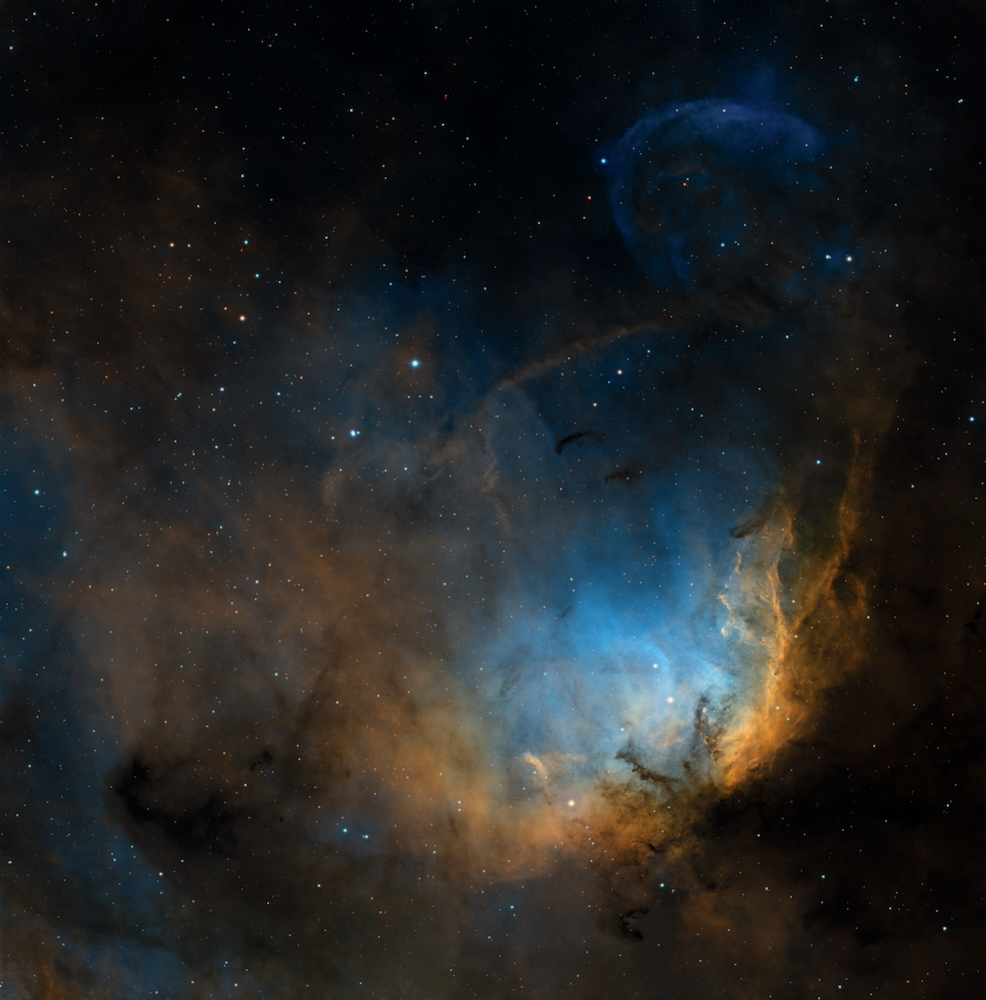

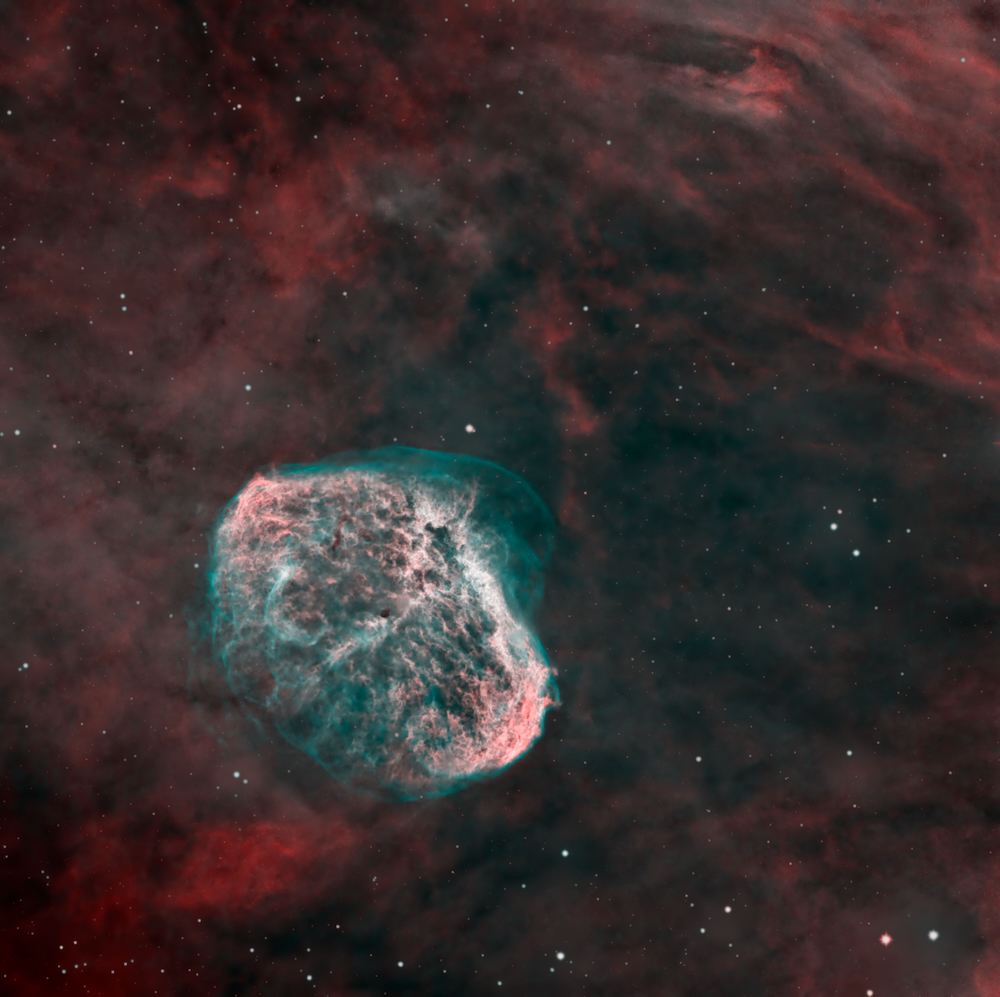

We then have a wrinkle that conventional photography doesn’t have, narrowband imaging. We use narrowband filters to photograph an emission nebula, or a planetary nebula, or supernova remnant. They have the advantage in that they cut out almost all of the light pollution and allow us to see things that just aren’t visible in a broadband image.

Many of these nebula actually aren’t reflecting light they’re emitting light. They work much like a neon light does, where bright light from a star comes in, energizes the electrons in the atom. When those electrons drop in energy, they emit a very specific color of light – red for hydrogen, a deeper shade of red for sulfur, and kind of a teal for oxygen. Those are the most common filters we use.

Most of the universe is hydrogen (95%), and hydrogen emission dominates everything.

When we can separate hydrogen, sulfur, and oxygen, we can see the details in lower value emissions and can bring them forward in the image to show them in a way that wouldn’t be possible with a conventional broadband image.

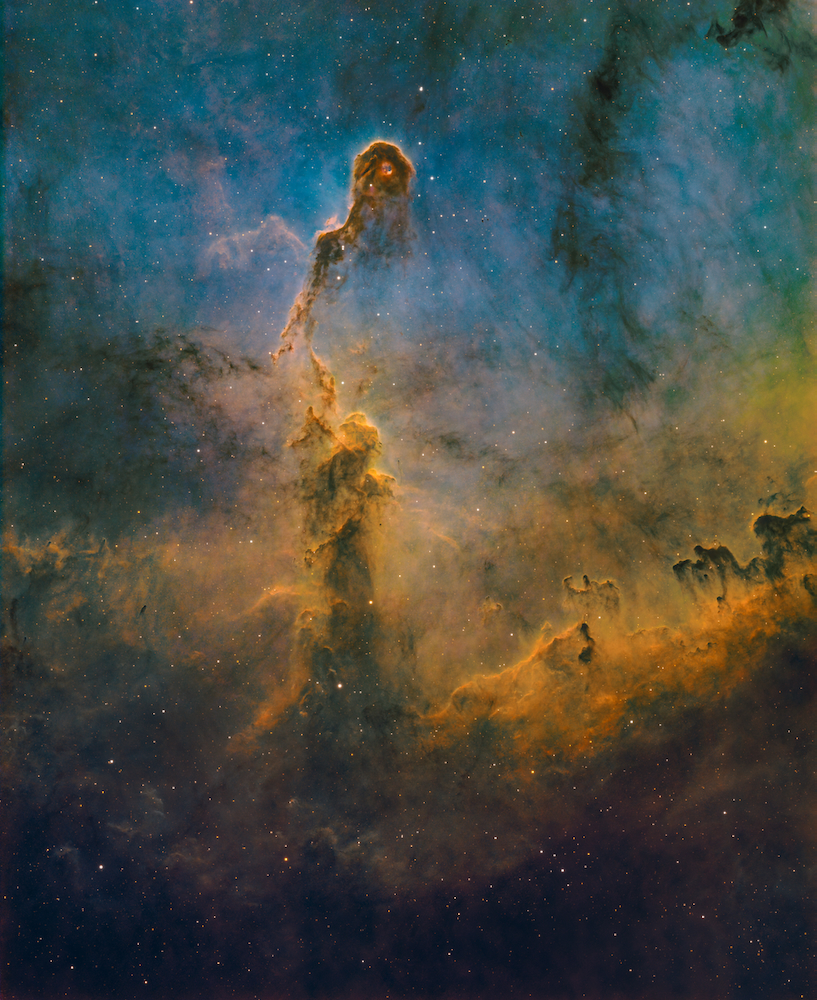

That’s where creativity comes in. You have complete freedom in how you put these things together. Some people use the Hubble palette, where they put the sulfur signal in red, the hydrogen and the green and the oxygen in blue. If you do that, you get an image that’s overwhelmingly green because hydrogen dominates. There are a lot of different techniques to tame the green. The result is a blue-gold image, which has been very popular in astrophotography circles.

There’s another technique where you put hydrogen in red and oxygen in green and blue, which has been done for a long time. That’s called an HOO image; it approximates real colors. Next, you can blend the sulfur signal in as yellow or some other color. I’ve been having a lot of fun in that technique because it gives the feel of a broadband image, but it gives you the detail of a narrow band image… and you don’t have to fight that green problem.

Tell me about favorite images – terrestrial and astro.

The image I just took of my grandson is a favorite. He was lying on the couch, the light was shining in from the doorway, it caught his eye and made it glow. It just captured him perfectly.

There are 2 astroimages that stand out for different reasons. The first is the image of the Wizard Nebula, the way the colors came together took my breath away. I used the technique that puts hydrogen in red and oxygen in green and blue with sulfur in yellow. It created depth in the nebula and showed it as if it was lit from within, which truly it is. It said “space” to me as much as anything I’ve ever imaged. I don’t have the words to say why this image keeps drawing me in, but it definitely does.

The great thing about that technique is you can use it to define edges and create a layering effect you just often don’t get in a normal SHO (Hubble Palette) image. It depends on where the sulfur is in the image but it can be very effective.

The second is the Tulip Nebula and the Cygnus X1 Bow Shock. This image is a 2-panel mosaic (panorama). I love the bow shock in the upper right corner. This is this is one of those cases where you say to an astronomer, “Do you want to see a black hole?” Of course, the answer is well we can’t unless you have a radio telescope the size of the Earth. This is as close as an amateur is probably ever going to get to imaging a black hole. If you look at those two bright stars that are on the right-hand side toward the top, there’s one that’s a little yellowish. That’s the star that’s co-orbiting with the black hole. The black hole is accreting material from that star or maybe from other places that have come into that star system, and it creates the accretion disk. As that accretion disk heats up, as the material spirals in toward the black hole, it gets hotter. Some of the material ends up escaping as a jet that’s moving a sizable portion of the speed of light, and that jet runs into the interstellar medium and it creates that blue bow shock. This is one of those SHO images, so that blue is oxygen that’s being excited by the jet from the black hole. We can’t see the black hole, but we can see the side effects from it.

What would you want a fine art audience to see in your work?

I would want them to see that there is amazing beauty in the night sky. There is amazing energy – and destruction – and danger from some of these things, but they are also incredibly beautiful. I tend more towards the analytical side than making it artistic. I try to make it look nice, but I’m not thinking primarily about art, but showing what’s there. effects from it.

I know you think about things like composition, depth of field, and focus. I think those are all elements of fine art. So, if you’ll allow me, I do think you are an artist.

I do think about those things, so I guess I get to qualify as at least some degree of artist.

How would you describe your style as an astrophotographer?

My goal is to go relatively deep. When you start astrophotography, you’re so excited to get an image that if you spend two or three hours on a subject, that’s a long time. But as you start to gain some experience, you realize that the more time you can spend on a target, the more faint details you can see, and the easier it is to process the image. I tend to spend anywhere from 20 to 60 hours on each target. I’m lucky because I’ve got access to an observatory that gets ~300 clear nights each year.

In terms of my style, I’m not looking to create things that aren’t there. I am perfectly happy taking things that are very faint in the image and bringing them forward. I think that’s where a lot of the technical challenge is – and a lot of the art.

It’s important to decide what story you’re trying to tell in your image and tell that story. That’s probably just as true for conventional photography. It doesn’t need to be complicated. It could be as simple as, “Look at this beautiful nebula, or, Look at these amazing galaxies.”

If you look at the Dumbbell Nebula through a telescope, you’ll see that it looks like its name. You see something that looks bulbous at the ends and narrow in the middle, and you can see why they called it the Dumbbell Nebula. However, if you look at it through a bigger telescope, or you take a picture of it with even a modest telescope, you’ll see that there are extended lobes and it looks more like a football. If you spend a lot of time imaging it, you’ll see that there’s even fainter extended fringes that are seen in my image. That’s the story I wanted to tell. This nebula isn’t just a bright core; there are successive waves of off-gassing from the star as it changed from a red giant to a white dwarf. This happened over thousands of years. There are faint outer layers, faint middle layers, and bright inner layers. The story I want to tell is of successive layers of an onion. This image is almost 41 hours of exposure time.

On astrophotography in general:

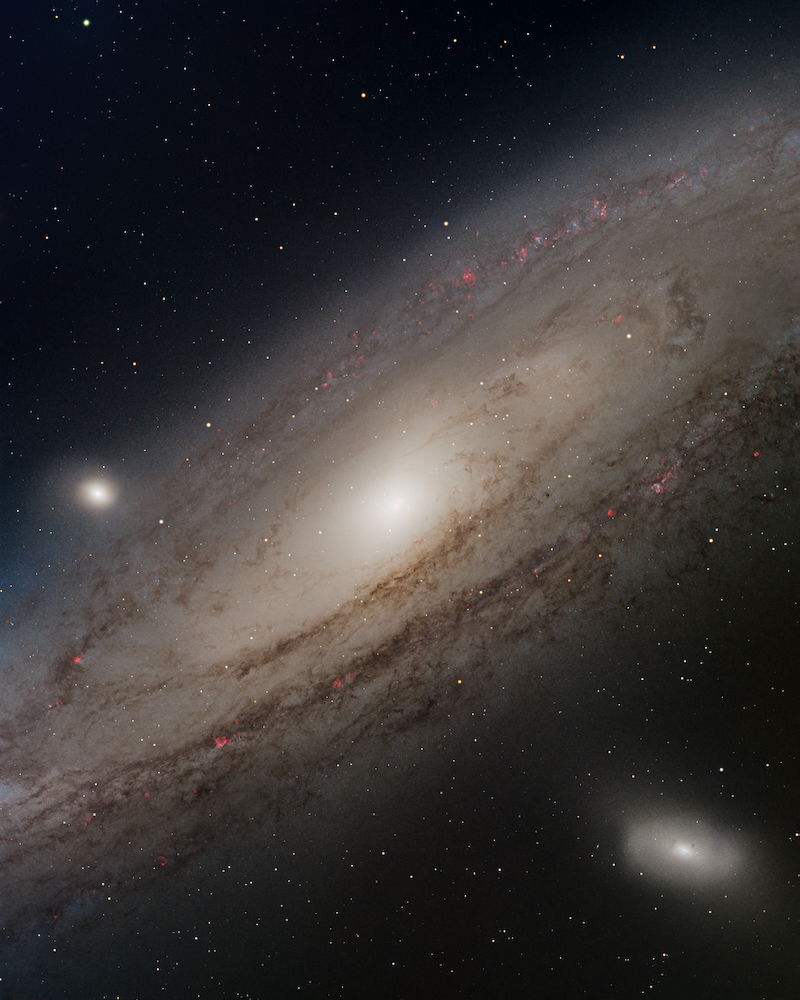

It still amazes me that with amateur telescopes, and granted these are nice amateur telescopes, we can see stars in nearby galaxies and resolve them. It boggles my mind that we can see a little star two million light years away as a distinct star.

Astrophotography is really good at making you feel small. When you look at something like the Andromeda Galaxy, and that image is too big to fit in the field of view of that camera and telescope, it covers six full moons end to end. Consider that it is two and a half million light years away and it’s that big in our sky. That’s one way to make us realize that the Earth is really a very small place in the universe, and there is a vast universe out there that’s taking basically no notice of us.

All the things that we think are important to our own lives, on an astronomical scale, are pretty insignificant. Maybe that that should get us to rethink some of our own priorities and the way we deal with each other

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Astrophotography: Andrea GironesNovember 8th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Linda Thomas-FowlerNovember 7th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Craig StocksNovember 5th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Adam BlockNovember 4th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Marsha Wilcox: Ancient LightNovember 3rd, 2025