Astrophotography: Adam Block

©Adam Block, This celestial butterfly is (another) example of a dying star with expansion of its outer envelope of gas. This gas glows various colors due to radiation of the central star (hidden behind some dust in this case).

Adam Block is one of the most well respected astrophotographers in the world. His images are published as references in academic journals and magazines. More than 100 of his images have been chosen by NASA as the Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD). Throughout his career, he has made fundamental contributions to both the art and science of astroimaging. He is a generous and gifted teacher. Many in the astrophotography community have become better imagers through Adam’s instruction. It was indeed a privilege for me to spend some time with him.

Throughout his public outreach career his passion centered on sharing the joy of understanding the world around us. While Adam’s voice always carries this message, Astrophotography has greater reach and compelling images, both technical and expressive, are seen by a world-wide audience. It is this life-long mission to offer the invitation to look upward, to think deeply, and to participate in the shared pursuit of understanding the Universe.

From 1996 to 2016, Adam Block shaped astronomy outreach programs across the American Southwest. After studying astronomy and physics at the University of Arizona, he joined Kitt Peak National Observatory and developed new stargazing experiences for the public. Later he founded the Mount Lemmon Sky Center for Steward Observatory, creating programs using some of the largest publicly accessible telescopes in the world.

Adam Block’s Masterclasses on Astroimaging

Adam’s Images on Astrobin

An interview with the artist follows.

©Adam Block, When stars reach the end of their lives they can do so in a number different ways. IC 5148 is an example of the way our own sun will evolve in the far future some 5 billion years from now. We see the shells of gas that are flung away from the exposed core of the star. The central region required advanced image processing as well as an artistic understanding of the nature of the data. (I can explain if you want… but basically has two bright emission lines here. My pre-visualization of this object was that I wanted to show the H-alpha emission more strongly in the center- so I differenced the data and applied some fancy processing to achieve this. The successful execution comes from my experience in understanding the tools and techniques.)

Marsha Wilcox: Tell us about your journey in astrophotography.

Adam Block: My interest in astronomy began at an early age. My parents bought me a toy telescope when I was 4 or 5. You can’t see very much through a toy scope. It was a test of your commitment and your interest if you survived that experience. They bought a very nice first telescope called an Astroscan for me a little later; it was the first piece of equipment with which I could see the sky and what was in space.

I always had a desire to share what I was seeing. I thought it was interesting. I would encourage my parents and my friends to look through the telescope and see what I was seeing. My parents bought an 8-inch Celestron for me when I was 12 or 13, and my uncle gave me a Pentax camera. I was able to use my camera with that telescope and take some pictures.

If you look at my photography as a young person, there are no people in the photographs. It’s birds, the sky, rainbows. Some pictures of space. I wanted to capture the world around me with photography. Astrophotography was an important part of that.

Did you do nightscapes?

No. Where I lived, outside of Atlanta, Georgia, there were no skyscapes to be seen. The first dark sky I had an opportunity to see was at Villa Rica. When I was there 40 years ago, it was dark, it was also winter. I saw the winter Milky Way, which was exciting … not as exciting as the summer Milky Way. I had to wait until I went to college to see that. The winter Milky Way was great, and I took pictures, attaching the camera to the top of the telescope. This allowed me to take pictures of Orion.

One of the very first real surprises for me was Bernard’s Loop in Orion. When I got my (film) pictures back, I could see the little pink blob of the Orion Nebula (Messier 42). I could see the Horse Head Nebula, but then I saw a large red arc in the image. I wondered what it was. Burnham’s Celestial Handbook told me I had captured Bernard’s Loop, a supernova remnant. Astrophotography for me was literally a way to discover the universe.

What was next for you?

I went to college at the University of Arizona. I came here to study astronomy and physics. While I was here, I ran programs at the vampus observatory as the head telescope operator. If you’re a telescope operator, you have a key. You can get into the observatory anytime you’d like and use the equipment. I would take every opportunity I could. My peers would go to the football game. I was at the telescope. This was at a time for astrophotography when the first digital sensors, CCD cameras, were coming out.

The camera we had was tiny compared to today. That was the beginning. I would hook that camera up to the telescope – which was not designed for this kind of thing at all. It is a 21-inch telescope at F15. The field of view was tiny, and with the tiny chip, even smaller. I started to try to understand how to do CCD imaging. There were no resources. It was the “Wild West” at the beginnings of CCD imagery. I was very fortunate to begin my formal career in imaging at the time that those detectors became available, and film transitioned out. This would have been ’92 or ’93.

Were you doing art and science then, or just science?

There’s no delineation for me. For me, it was all about trying to understand how to capture the sky with the resources I had at hand. After I graduated with a degree in astronomy and physics, I didn’t know what I was going to do. I thought I would try to get a job with Sky and Telescope or Astronomy Magazine because I figured I had the skills to write articles, and I was getting into the graphical part of astronomy. Kitt Peak National Observatory advertised they wanted to have a nightly public program. They needed someone who understood telescopes, knew where things were in the sky, and could explain things to run those programs. I had just spent years running similar programs for students. As it happened when I applied for the job, I was hired on the spot and worked there for nine years. In addition to the public outreach presentations, I also developed a formal astrophotography program. It was, as far as I know, the only program of its kind in the world that was dedicated to astrophotography. That was a lot of fun. I spent many nights with people using the cameras that were available at that time. Both the software and the cameras have evolved through time and improved dramatically.

After my time at Kitt Peak I wanted to expand on the work I was doing. I ventured out on my own and approached the University of Arizona about developing a better program. They agreed, in part because other individuals lent their support by donating equipment, including what became the Schulman Telescope, a 32-inch telescope. The program is the Mount Lemmon Sky Center and is now considered a destination for visitors.. I was very grateful to have had that opportunity to express myself through the program. I included an astrophotography program as well.

I worked nine years on that program as well. I still work in the Department of Astronomy for the University of Arizona. In 2016, I began working under another astronomer in a completely different area called “space situational awareness”. The study of satellites their attributes, and their orbits around the earth and moon. I’m working to present information in a way that is more interesting than the raw data. There is an art to that. We use an astrograph (a widefield telescope designed exclusively for photography) for the work. I use it to take images when we’re not using it for measuring satellites.

Tell us about your new telescope in Chile.

My new telescope was installed in Chile this year. By fortunate means, I came upon a wonderful telescope. It’s a long story; it was a donation from the family of a gentleman I helped while I was at Kitt Peak. It’s a 24-inch telescope, the Harris telescope, named after my benefactor. It took more than two years to finally commission the scope. It is up and running now and working very well. It’s in the southern hemisphere, a whole new sky for me.

Tell us about your astrophotography process.

I see it like Ansel Adams pre-visualization. I don’t know if it’s the way that he meant it, but it is the way that I interpret it. I look at that image not for what it is, but for what I want it to be. I start to form a picture in my mind of what I hope the final image will look like, given the colors, the brightness levels, etc, that I see in the raw data. I see all that information, and I know what is there. I want to express as much as I can in my final rendering of an image. There is a huge dynamic range. There are colors that are often very subtle, you may want to try to make those more apparent. Contrast is also important.

You need to take a step back and appreciate what is recorded in your image. When I’m looking at my raw images or later, the stacked image, I’ll look at it in different ways and different brightnesses and so on, to get an understanding of what’s there.

I also know it’s a journey to get there. I make decisions about how I adjust something – smoothness, brightness, color, blending things together, etc. Some of those bits may not survive decisions that I make. The game is to make decisions where I maintain all of the features I see in the original data. At the end of the day, I want you to be able to look at the picture and not know what I did. There’s a naturalistic element that interests me.

There are images where it’s necessary to do a little more, due to the nature of the object. Recently, I took a picture of IC 5148, which is a planetary nebula [an expanding shell of gas around a dying star]. It has nearly equal amounts of signal in hydrogen-alpha (red) and oxygen (teal). If you take it as is and blend it together, you’re going to get something that does not look very good. That’s not what I visualized. I already know the nebula is primarily oxygen. What I want is to show the green, but in the center where the hydrogen lives, where the hydrogen emission is in excess of the oxygen glow. If it’s equal to the oxygen, then I’m not interested. I know that the hydrogen-alpha emission will look good in that sphere of greenness because it will show the structure that is embedded in all of that brightness. So, I devised a strategy to capture the excess hydrogen-alpha information. That allowed me to reach the vision I had for that picture.

If you do just straightforward processing, you’ll never get that picture. I’m hoping that when you look at that picture, you won’t know what I did. It just looks like that’s the way the object should be. I did a lot of work to get to that point. IC 5148 is an excellent example of that struggle.

©Adam Block, This object is an example of a globular star cluster. They contain tens of thousands, hundreds of of thousands and sometimes even millions of stars. This one, though not large, is one of the closest to us. I think it is one of the most beautiful examples.

©Adam Block, (Inset) This object is an example of a globular star cluster. They contain tens of thousands, hundreds of of thousands and sometimes even millions of stars. This one, though not large, is one of the closest to us. I think it is one of the most beautiful examples.

Imaging galaxies and deep-sky objects

When I look at images, I deconstruct them. I think about how I want to handle them based on the features or attributes or characteristics. For example, when I look at a globular star cluster, the stars are the primary concern.. You have one star, and then you have 100,000 in the cluster. Whatever decision you make, you’re going to be repeating 100,000 times. You’ll get all kinds of different results depending upon the stretch* that you do.

*[Astroimages are “stretched.” That is, the histogram is moved to the right in a nonlinear way. Stretching is an art in itself; there are many ways to do it.]

I make different decisions for star clusters, planetary nebula, and defuse nebulae. Some galaxies are diffuse, others are not. In each case, I deconstruct the image based on the features that are present and proceed accordingly.

©Adam Block, Comets are the most difficult object to capture well in astrophotography. This comet graced the sky in March of 2024. For several nights it was in the foreground of some famous objects including the Andromeda galaxy (which is 2.5 million light years away). This picture was taken with a regular DSLR camera (Canon Ra) and an very nice 85mm lens. A small astrotracker was also used. See : https://youtu.be/Bc7DWVgz8Ds?si=goPe3P36fMrOoeol

Galaxies tend to have a radial profile, they’re faint on the outside, but very bright in the center. I might compress the dynamic range to be able to show the inner structure as well as the outer glow of the galaxy. However, I still maintain a brighter center compared to the outer portions. To me, this is what makes my images, “natural looking.” That’s the decision that I’ve made there. (Many people are addicted to contrast and render images for the detail alone at the expense of other attributes.)

I heard a bit about what you’d like your viewers to take away from your images. What kind of responses do you get from your audience?

It’s a range – from folks who may have some science or astronomy background, to folks who don’t, who see your images for your art.

My images have been used as references by not only for people who do astrophotography but published as references in papers and magazines. I don’t get that many comments. comments because they look “professional”. Some people often think they are Hubble Space Telescope pictures for example. I think people like the pictures but the context matters..

I think people put me in the box of professional astronomer. They wouldn’t put me in a box as an artist. Sure, the pictures look good because I’m using the best images and best equipment in the world. I generally don’t get comments about the artistic decisions that I make, other than the fact that people either find them compelling or not.

When it comes to showing people who understand the process of creating the images, that kind of feedback is where you would have a better insight into people’s response. If they like the image, they’re going to be able to tell you why in terms of the image attributes as it relates to the subject, not just, that’s a compelling image.

©Adam Block, Here is a group of galaxies. The strangely stretched one at the bottom left is one of the largest known in the Universe (that we have seen). 5 or 6 of our Milkyway galaxies could transverse this behemoth.

You have talked about an ancient echo in night sky images. Tell me about that.

There is a cross-cultural appreciation of beauty in space pictures that seems to be shared by everyone. It is a shared response to images of the night sky. If you show astrophotography to someone who doesn’t know anything about space, you get a very good reaction. I think it’s not so much about my work, as it is a reaction to night sky imagery, or space itself.

There is something about pictures of space, and the night sky in particular, that I think is an ancient echo. I think that is part of the response you get from people in general.

Tell us more about the ancient echo.

You might have heard that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. There is a philosopher whose argument is that’s not necessarily true. There are evolutionary preferences for things that we find beautiful – in art, and nature, and performance, and so on. There is a world-wide shared reaction to these elements. It’s something deep within ourselves. It is an ancient echo of an evolutionary past that preferred these things.

Did you know there’s a preference for landscapes? It’s the most amazing thing. If you ask anyone to describe a beautiful landscape, the elements they list are shared by just about everyone in the world. They have a Hudson Valley-esque look to them. They’ll be green, they’re going to have a wide-open space, low trees, and usually a path. There will be indication of water, maybe some animal life. If you were going to survive a few million years ago, you would seek out those places because you knew that those would be the kinds of places that could support you. That preference is an ancient echo of a time when that was important.

That extrapolates to the night sky. If you were an ancient ancestor out in the dark, your body literally changed. You must rely on your hearing more than your sight. What was the only thing that you could see under these dark conditions? It was the starry night sky.

My argument is that, just like landscapes, there is an ancient echo. I think that there is a burned-in night sky archetype for which we have a preference. This applies to astrophotography. People want to see those elements in their images. You have the night sky. In nightscapes, you have the sky and you have the earth down below. That is the archetypal scene that is compelling. It is a rendering of that ancient echo, literally.

©Adam Block, One of the popular ways to take pictures in astronomy is by observing nebulae using narrowband filters. This allows the capture of specific colors that the nebulae glow strongly in. An object like the Rosette nebula is a great example.

©Adam Block, (Inset) One of the popular ways to take pictures in astronomy is by observing nebulae using narrowband filters. This allows the capture of specific colors that the nebulae glow strongly in. An object like the Rosette nebula is a great example.

Tell us about your narrowband imaging.

Narrowband work is something that is relatively new for me. For most of my career, I was just doing broadband.

You need to take very long exposures for narrowband; there’s not much light in each of the specific filters. When I got started, the idea that you would spend 50 hours on an object wasn’t even a thought. It was extravagant if you spent two hours taking a picture of an object. Now, with my new telescope, I have the ability to do it.

Narrowband is a much more fluid kind of astrophotography. There are fewer constraints. When you’re doing broadband imaging, you are constrained if you want to get a reasonable, natural representation of the object. Narrowband is much more relaxed. Some astrophotographers are relatively true to the observed colors, others take great liberty with tone and color mapping. There is no right way to do things. There are just fewer constraints.

©Adam Block, The Whirlpool galaxy is a grand spiral and it is strongly interacting (colliding) with its smaller neighbor. This is an extremely high resolution image given the semi-professional equipment. These galaxies are around 30 million light years away.

The image of the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) is an example of one of those images that I took years ago. In order to show what makes the image special, we have to zoom in so far it would be hard to see the entire galaxy. What’s nice about the Whirlpool Galaxy is all the detail that’s there. You can see the actual image quality by zooming in a little bit. Here are the full image and 2 insets showing fine detail in both galaxy cores.

©Adam Block, (Inset) The Whirlpool galaxy is a grand spiral and it is strongly interacting (colliding) with its smaller neighbor. This is an extremely high resolution image given the semi-professional equipment. These galaxies are around 30 million light years away.

©Adam Block, (Inset1) The Whirlpool galaxy is a grand spiral and it is strongly interacting (colliding) with its smaller neighbor. This is an extremely high resolution image given the semi-professional equipment. These galaxies are around 30 million light years away.

Tell me about your favorite images.

My favorite images are usually the ones that I haven’t done before. I’ve taken a picture of the Orion Nebula a gazillion times. That’s not to say that I won’t revisit it every decade or so. I do like the novelty of things, even if the novelty is very subtle.

For example, I recently took a picture of NGC 1055, which is an edge-on galaxy. That one is interesting to me because years ago, I tried to take a picture of it. The instrumentation wouldn’t allow it. I had the scattered light in the frame. Recently, with my new telescope, that was not the case. I could spend time on NGC 1055 and capture some great data. The deep images didn’t show me anything new per se. I wanted to get a high-quality result because I had never achieved that with that object before. It was nice for me to see that at the end of the disk, there’s a very faint blueish loop that I hadn’t seen before. It’s the kind of thing that unless you do really deep images, and you process to show that kind of structure, you won’t see. That image made me happy. It was my novelty for that object. Even though it wasn’t fully the object, it was an element I liked.

IC 5148 (green and red planetary nebula above) is a new favorite. I had to wholesale think of a different way to represent that. I couldn’t just apply any of the normal ways of thinking about representing the information. It is a favorite because I was able to think of a different way to approach data and come out with a result that looked compelling to me.

©Adam Block, This is an image that captured the Sun’s corona during the Great 2017 Solar Eclipse. The moon can be seen as well due to Earthshine. Simply nothing is in this world is more dramatic than blotting out our life-giving Sun- even for just a few minutes.

©Adam Block, On September 27th 2025 Comet Swan brightened dramatically. This cumulative 30 minute exposure captures the streams of gas being pushed away from the nucleus by the solar wind.

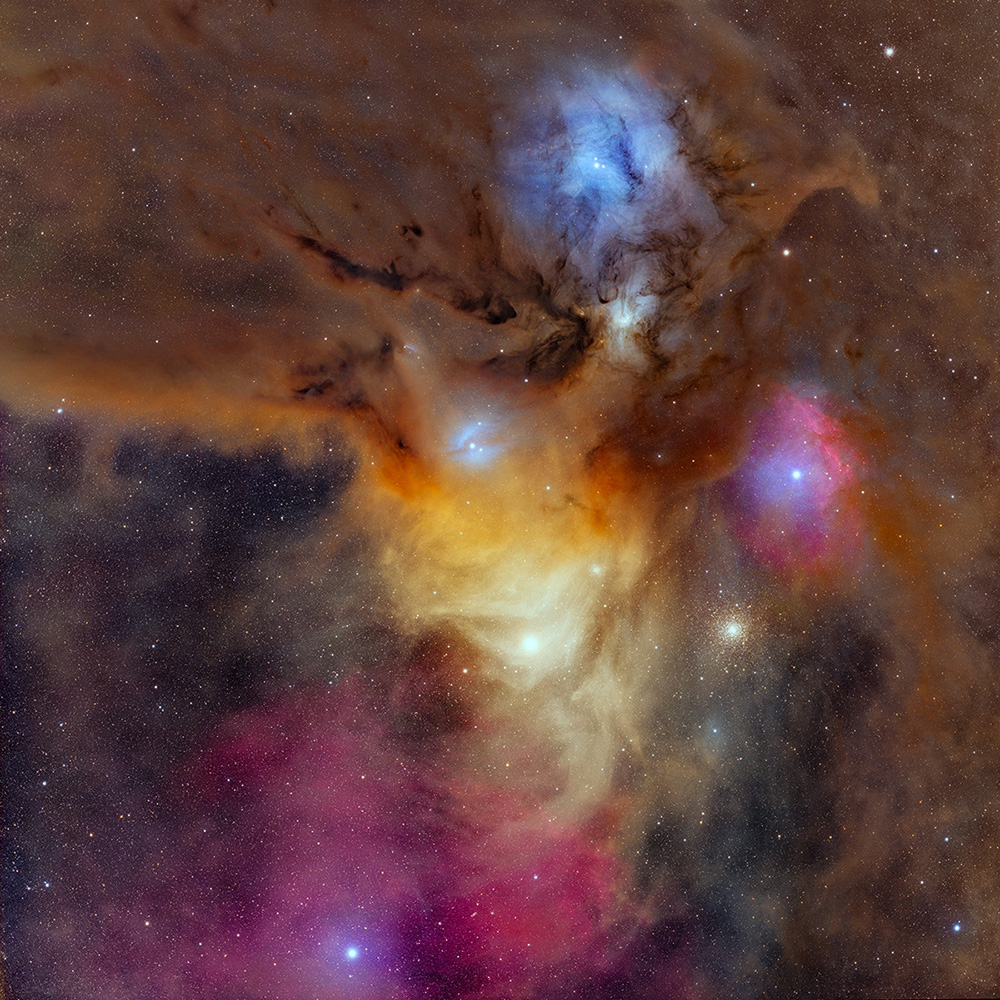

©Adam Block, Adam is particularly noted for this image of the Pleiades. This is one of the most famous objects in the sky and creating a picture that offers a different perspective is a challenge. Here the colors of the stars, gas and dust taken together make this a visual feast.

©Adam Block, The region of sky near Antares, in Scorpius, and Rho Ophiuchii is awash in color and light. These stars and clouds of dust are some of the nearest nebulae and are seen against the background stars of the Milky Way. Careful choices in processing render the delicate dust clouds which show off the real depth of the image.

©Adam Block, These two galaxies are hundreds of millions of light years away from us. On the date I took this image earlier this year there were no other high resolution images of this pair. This will not always be the case. Soon the entire sky will be recorded to a limiting magnitude that goes well beyond amateur equipment. But… I like this object because my image referential since there are no others prior to mine.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Astrophotography: Andrea GironesNovember 8th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Linda Thomas-FowlerNovember 7th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Craig StocksNovember 5th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Adam BlockNovember 4th, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Marsha Wilcox: Ancient LightNovember 3rd, 2025