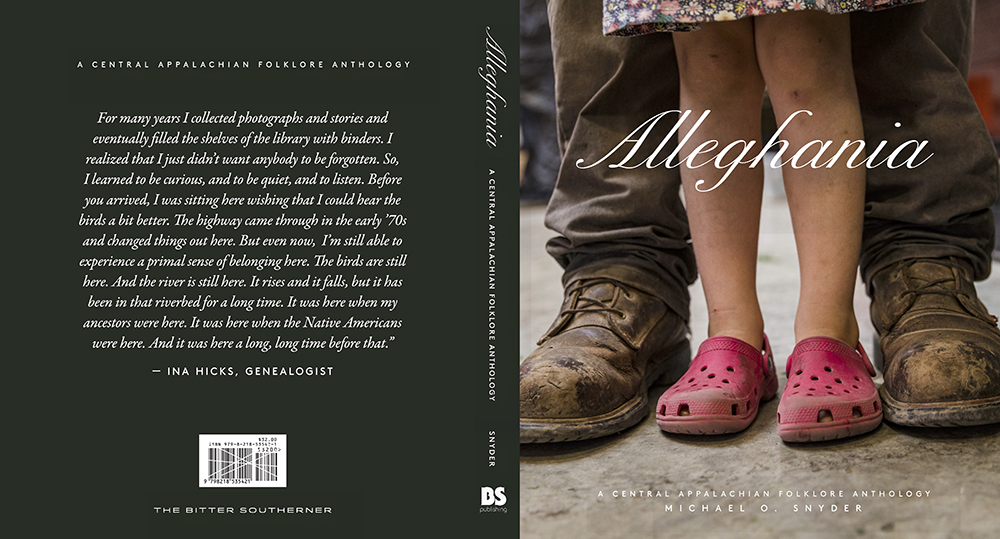

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore Anthology

Photographer and filmmaker (and Lenscratch Environmental Editor) Michael O. Snyder, has created a stunning monograph, Alleghania: A Central Appalachian Folklore Anthology, set against the ancient landscape of the Allegheny Mountains, filled with s a collection of portraits from rural America. The book is published by The Bitter Southerner.

From farmers and herbalists, to skateboarders and train hoppers, Buddhist monks to Christian pastors, this is a love letter to an often overlooked part of Appalachia – a place where tradition and transformation intertwine. Alleghania asks us to reconsider our image of a region and its people. Snyder’s new body of work brings Central Appalachia’s grit, grace, and heart clearly into view.

“Appalachia, a region deeply synonymous with tradition, is changing faster than any time in recent history and perhaps faster than anywhere else in America. The internet, the global economy, and the widening of roads have all co-conspired to bring attention and change to a region that robustly resisted it for generations. Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore Anthology tells the stories of 77 individuals who are carrying forward Appalachian traditions in our rapidly changing world, challenging long-held notions of cultural rigidity in Appalachia, and exploring the heritage of the region as a rich, diverse tapestry of traditions that is inclusive of a plurality of voices, identities, and perspectives.”

The book can be ordered HERE.

Michael O. Snyder (b. 1981) is a photographer and filmmaker documenting the climate crisis and related social-environmental issues. In addition to creating visual stories, he is deeply interested in how our narratives can help drive social impact.

His work has been featured by outlets such as National Geographic, The Guardian, and The Washington Post. He’s been honored by awards such as the Portrait of Humanity Award (Winner), the Decade of Change Award (Winner), The Welcome Prize for Photography (Shortlist), the LensCulture Portrait Awards (Finalist), and the Visualizing Climate Change Award (Winner). Snyder is a Pulitzer Grantee, a Climate Journalism Fellow at the Bertha Foundation, a member of the Society of Environmental Journalists, and an Assistant Professor of Visual Communication at Syracuse University’s Newhouse School in New York.

Through his production company, Interdependent Pictures, he has directed films in the Arctic, the Amazon, the Himalaya, and East Africa. His films have been selected to over 60 festivals, have taken home numerous awards, have been sponsored by companies such as Sony and GoPro, and have been distributed by outlets such as New Day Films and Films for Change. Michael often lectures on visual storytelling and its potential as a tool for social impact. He has been a featured speaker at the United Nations Climate Conference and has lectured at universities such as Yale, Columbia, and the Alfred Wegener Institute. In 2022, the University of Edinburgh named him one of its most “influential alumni making a significant contribution to climate science and justice.”

An adventurer at heart, Michael has hiked the Appalachian and John Muir Trails, cycled across Europe, and ridden trains through Siberia. Originally from a small town in Appalachia, Snyder has lived around the world including long-term stints in Scotland, Japan, Hawaii, and New Zealand. Michael holds an MSc in Environmental Sustainability from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, where he was a Rotary Ambassadorial Scholar, and a BSc from Dickinson College, Pennsylvania.

Instagram: @michaelosnyder

Instagram: @bittersoutherner

Opening essay to the book

When I was six years old, I took it upon myself to teach our kitten how to climb trees. Being something of a celebrated expert in the matter, I reasoned I could be of assistance. We were three limbs up the magnolia when the cat dislodged herself from my grasp and sprang nimbly to a nearby branch. On her way, she expressed her gratitude for the instruction by passing her claws through my upper lip, leaving a wound that my mother fretted over, and I picked at until it became a scar — still visible to this day.

In school, weeks later, I got in a fight with Ronnie Fazenbaker. The cause of the incident wasn’t altogether clear, but there was speculation that my newly acquired battle markings had garnered the attention of Ronnie’s ladylove. As it occasionally goes with these things, boyhood fights lead to casual friendships, and in the summer of the following year it was Ronnie who taught me how to watch out for sinkholes in the woods behind our homes. These depressions were the product, I learned, of collapsing mine shafts that crisscrossed the mountainside like decaying veins in an arm.

As a newcomer to coal country at age six in the 1980s, this seemed like pretty vital information. Sunken mine shafts were evidently the Appalachian equivalent of quicksand, and if Hollywood had taught me anything, getting slurped underground was a fate worth avoiding. I gleaned other pertinent pieces of knowledge from the kids who lived on the hill: How to know which mushrooms will kill you if you eat them. How to gut a fish. How to seal a wound with superglue when you screw up gutting a fish. And how to turn an old carburetor from the junkyard into a pretty convincing timebomb. Becoming country felt like a natural and exciting process, and I took to the task with gusto. I suppose I had a leg up in the matter, as I wasn’t entirely un- country before the move to our home in Western Maryland. My mom and dad were from small towns in Pennsylvania and Indiana, respectively. But when you move from anywhere to somewhere else as a kid, you’re keenly aware of your presence as an interloper. Doubly so if you happen to be moving to Appalachia, a region famous for its insularity.

Ronnie, by contrast, came from a family that, as far as anybody knew or could recall, had sprung from the hills along with the moss and morels. He was from what we called “the old families.” Bittingers and Beemans. Whetstones and Walkers. Yutzys and Yoders. Finzels, Folks, Fikes, and — of course — Fazenbakers. This network of folks could trace their names back to the first Scots-Irish and German settlers who began to occupy these lands at the edge of the colonial wilderness in the 1700 and 1800s. It was a place that, in many ways, felt out of time. Everything here seemed to be existing at least 10, if not 15 years in the past from the rest of the country. And so, for the most part, my childhood world encompassed about 12 acres of forest, seven channels of television, and several books from the regional library. The edge of the county was essentially the edge of the world. And I loved it.

As time passed, I grew up. And so did Appalachia. First came the widening of highways. Then there was MTV and Walmart. And finally, the internet, a force that slowly, but irresistibly, brought news of the world to a region that had lived in relative isolation for generations. But with inflow, came outflow, and like many Appalachian youth in the 1990s, I saw a bigger world and availed myself of it, leaving first for college and later for work. No doubt influenced by the adventure stories that filled my childhood and an early life spent outdoors, I became a documentary photographer, focused on the relationship between cultural change and environmental change. Almost two decades passed before my wife got a job offer at the University of Virginia and we moved from Washington, D.C. to a small house in the Blue Ridge Mountains — a stone’s throw from my childhood home.

Coming home to Appalachia in the twenty- teens, I found many aspects of rural life to be exactly — and pleasantly — where I had left them 20 years prior. Fran was still behind her sewing machine in the fabric shop on Main Street. The diner still served burnt coffee water with all-day refills for a buck-twenty-five. Country highway billboards still cheerfully proclaimed that God was blessing America’s troops and fetuses. And the first day of hunting season was still cause for a near complete societal standstill. But closer inspections yielded curious observations. The diner now had something suspiciously called a “latte.” Hunting season now took an official timeout for Cyber Monday shopping. And more arrestingly still, the newspaper was now advertising something called a “trailer park drag queen show” at the local theater on Thursday night. While I took an easy pass on the latte, the hillbilly drag fest was simply too irresistible to miss, and mere minutes after folding up the paper, I was sliding into my seat, ticket stub and Budweiser in hand. On stage were the same small-town folk I had long known, including a gas station attendant I recognized from high school, but now wearing 4-inch heels and gyrating to K-pop on stage to the enthusiastic cheers of a large and diverse crowd. Yes, queer culture was here in the 1980s, but it wasn’t on Main Street and certainly not on a school night. Something important had changed.

At the same time, as it seems to happen every so often in American politics, the country woke one morning and remembered that its rural 6 citizens still existed. Appalachia, conveniently lost for a few decades in the mists that shroud its mountains, was suddenly rediscovered and thrust into the national dialogue in the 2010s. The 2016 election, the opioid crisis, and books such as Hillbilly Elegy, pushed open the door and a thousand-and-one perspectives on the lives of country folks came pouring in. Statistics were sourced. Experts extolled. Pundits pontificated. But one thing seemed curiously, if conspicuously, absent from the discourse: What do actual country folks have to say for themselves?

Out of all of this, the “The Mountain Folk Project” (at times also called “The Mountain Traditions Project”) was born. The goal, put simply, was to shut up and listen to what mountain folk have to say. More specifically, to shut up and listen to what a diverse cross section of mountain folk have to say about how tradition, culture, identity, and daily life are changing (or perhaps are staying the same) in the 21st century. The project got its official start in 2011 with a small regional arts grant and guidance from Dr. Kara Rogers Thomas, a folklorist at Frostburg State University in Maryland. An initial run of six interviews in 2011 grew to 86 profiles over the course of the following 13 years, the final product of which you are holding in your hands, a book now titled Alleghania: A Central Appalachian Folklore Anthology.

While this book has “folklore” in the title, it is not, strictly speaking, a traditional folklore project, as I haven’t made any attempt to follow a rigorous methodology, or to produce something intended for academic consideration. Rather, this is principally a documentary project, created with the goal of showing what is, what is often overlooked, and what may yet be. It’s also critical to stress that this book makes no attempt, or claim, to speak for the whole of Appalachia. For starters, Appalachia is not monolithic in culture, identity, or perspective. As such, there is no “whole” to it. Also, this book is not remotely inclusive of everyone who is “mountain folk” and everything that could be considered an “Appalachian tradition.” There are numerous omissions, not least of which, Native American traditions, which were largely, and intentionally, eradicated from the region beginning in the colonial period, and extending through to the modern day.

So, I think it would be prudent to offer a word at this juncture as to what is included in this project, and what isn’t, and why. There are two questions in particular that need to be addressed:

What is “Appalachia,” and what part of it are we exploring?

Who are “mountain folk,” and how were they selected for this project?

Let’s tackle the first question, first: What is Appalachia and what part of it are we exploring?

In the broadest and most geologic sense of the term, Appalachia is a physiographic region whose formation began over 480 million years ago when four continents collided in a slow- motion cataclysm that heaved the earth skyward and created a chain of mountains that would rival the modern-day Himalayas in size. In the ages that followed, the patient and persistent action of ice, wind, and rain reduced these giants to smaller but still respectable nubs; a band of rippling ridges, forested hills, and valleys that today stretch over 2,000 miles from the state of Mississippi, in the south, to the shores of Newfoundland, Canada, in the north.

The more human centered, and perhaps most widely accepted definition of Appalachia is the one put forward by the Appalachian Regional Commission (the ARC), a federal organization established by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965 as part of his “War on Poverty.” The ARC today defines Appalachia as comprising 423 counties, spanning 206,000 square miles, and including 26.4 million residents in 13 states and three federally recognized and five state recognized Native American Tribal Communities.

While both of these definitions are quite reasonable and functional in their own right, I remain unconvinced that they serve a conversation about Appalachian culture, which cannot so easily be delineated by physiographic provinces or cut along county lines. As a general, and personal, definition of Appalachia, I prefer the following: If you live on the East Coast, can see at least one mountain out your bathroom window when you get up for a pee, and you happen to feel like you’re Appalachian, then you probably are. But, for the sake of The Mountain Folk Project, I had to go with something a bit more specific, if also somewhat more prosaic. It’s this: The Mountain Folk Project focuses on a geographical circle that is approximately 300 miles in diameter, with the center point roughly located in Randolph County, West Virginia. Or, put more succinctly, this project is really about the Allegheny Highlands subregion of Appalachia and the counties that are adjacent to it.

Why draw such a small circle? Well, frankly, it’s too damn expensive and time consuming to spend 13 years driving from Mississippi to Canada when you’ve got to pick up the kids from daycare at five. What’d you expect?

And why the Allegheny Highlands? What about Kentucky and North Carolina? Why am I leaving them out?

Well, this one’s personal too: The Alleghenies are where I grew up. It’s home and the place I know best. So, this project is intentionally, and unabashedly, centered around my own personal experiences, preferences, and connections. I would argue that, selfish implications aside, there is value in approaching this kind of project in an author-centered way. I find that the best documentary work is done in intimate collaboration between author and subject, building on a foundation of trust and mutual understanding. While this can be built between any two people, it comes most naturally when the photographer has something of a shared identity, knowledge, language, or experience with the subject. So, by choosing to work in the Allegheny Highlands, I’m deciding to tell the story of something that I am intimately a part of, rather than being a voyeur of something I’m not. I didn’t leave Kentucky out because I don’t like Kentucky. I left it out because I’m not from there.

Finally, beyond personal connections and preferences, I happen to think the Alleghenies are a beautiful, fascinating, and often over- looked region of Appalachia. They truly lie at the cross-roads of America: the intersection of industrial North and agrarian South, commercial East and wilderness West, a unique overlapping of Frost Belt, Rust Belt, and Bible Belt. Ecologically, economically, and culturally speaking, Alleghania is an awesome place. I hope you think so too.

Then, as for the second question: Who are “mountain folk,” and how were they selected for this project?

This one was a whole lot trickier. As I explained above, my tendency as a documentarian is to include, rather than to exclude. I’d rather put up a big tent and make room at the table than turn people away. So, for example, while some of the individuals in this book can draw their ancestral lines back to “the old families,” others in the book only recently moved to Appalachia, making it their home within the last decade or two. This bend toward inclusivity was deliberate, as I fundamentally believe we are all visitors here, and all who choose to be here should be welcomed as “mountain folk.” And, after all, I too am both an insider and outsider to the region. Second, I would argue that while documentary work should seek to be representational and show “what is,” it also has a responsibility to show what is often overlooked, and deliberately unseen. As such, I’ve tried to approach this project in a way that probes the edges of diversity in as many dimensions as possible, inducing, but not limited to, age, ethnicity, gender, identity, birthplace, culture, politics, religion, education, and socioeconomic status. And that means excluding neither the majority nor the minority perspective from the work. It also necessarily means over-representing certain identities and perspectives that wouldn’t be commonly found in a randomized cross-section of the region. I’m OK with that.

In many ways, this is a book about traditions — how they are changing, and what those changes tell us about mountain folk today. Wherever possible, I’ve approached the definition of a “tradition” in a way that celebrates culture as composed of a diverse tapestry of lifeways, and is inclusive of a plurality of voices, identities, and perspectives. I’m not particularly interested in looking at culture as a static, historical artifact, but, rather, as a dynamic, transformative force that is alive in the present moment and is constantly moving in tension between the norms of the past, and the cultural, economic, and technological movements of the present. As such, some of the traditions documented in this book are centuries old, while others have emerged within the past few years. Some individuals in the book learned their craft from a long line of master-and-apprentice-relationships, while others picked up their tradition around the home. And yet others Googled it and are figuring it out as they go. Some folks in the book are internationally recognized and celebrated as tradition bearers, while others were simply recommended to me by friends of friends, never thinking twice that what they were doing was particularly unique or special. But, regardless of who I was talking to for this project, I was principally interested in trying to understand who they are, what moves them, what is changing, what is staying the same, and what it truly means to be Appalachian today. As you will note in the text, the approach is highly informal and conversational. While the focus is principally on what they have to say, my voice remains present throughout. I’ve included myself both because I think it reads better that way, and also because I can provide some context where necessary. The short essays in the book are derived from conversations that sometimes went on for hours, only to be reduced here to the most salient points and comments. And, as a photographer, I do hope you like the pictures, but they are really just there to grab your attention. The beating heart of this book lies in what mountain folk have to say for themselves.

As an epilogue to my opening story about Ronnie Fazenbaker, I found out in 2009 that he had died. The obituary was short, and the cause of death wasn’t clear. The only thing that remains of him online is a grainy black-and- white photo that accompanied the obituary text. The truth is, Ronnie and I had parted ways early on. Our lives took very different paths. We weren’t friends in high school and probably hadn’t spoken since the age of nine or 10. Ronnie probably fits into most people’s stereotype of a young Appalachian man: undereducated, underemployed, and under the ground before his time.

But there is something else about him that nobody knew, and I want you to know now. It was Ronnie Fazenbaker who taught me how to play chess. It was on a rainy day in third grade, and we weren’t allowed to go out for recess. Ronnie was already slipping in his studies and had been moved by the teacher to the back of the classroom. But he came up to me that day and asked if I wanted to play a game with him. He knew all of the moves and even taught me some basic strategy. Not many kids in my area knew how to play chess at that age and goodness knows where he learned. I discovered that I loved chess and kept playing when I was in high school and in college. I still do. And when I taught my son how to play, I made sure to tell him that it was Ronnie Fazenbaker, an Appalachian hillbilly, who taught me how to play the world’s greatest game of the mind.

©Michael O. Snyder, The Roller Derby Captains, Kristy Richmond (Squee J) and Tianna Bogart (Boo T Bot)

I share this with you now because, as you explore this book and consider Appalachia, I want you to hold in your mind the notion that there may be more to mountain folk than meets the eye. And remember, as you think about how you can contribute to the conversation and support a region that has had its share of struggles — cats don’t need to be taught how to climb.

©Michael O. Snyder, The Demolition Derby Team, Jason Sauer, TY McClelland, and Darrell Kinsel, Garfield Neighborhood, Pittsburgh, PA

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025