Meghann Riepenhoff: The States Project: California

Since 2012, I’ve been fortunate share work and review critical feedback with Meghann Riepenhoff. During that time she has significantly broadened my understanding of what a photograph is and can be. In requesting that I curate this group of photographers, Aline Smithson asked what I thought it meant to be a California photographer today. My two word answer would be Meghann Riepenhoff. Her work is intensely linked with the state’s landscape and an often experimental photographic history. For her, photographic exploration of a place is not just visual, but also elemental and physical. Meghann’s show Littoral Drift at SF Camerawork, much of which is featured here, was one of the most profound experience I’ve ever had with photography.

Born in Atlanta, GA, Meghann Riepenhoff is an artist based in Bainbridge Island, WA and San Francisco, CA. She received a BFA in Photography from the University of Georgia, and an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute, where she is a member of the visiting faculty. Her exhibitions include the High Museum of Art, the Worcester Art Museum, Galerie du Monde, San Francisco Camerawork, Higher Pictures, Euqinom Projects, Houston Center for Photography, and the Center for Fine Art Photography. Her work is in the collections of the High Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Museum of Contemporary Photography and the Worcester Art Museum, and has been published in Harper’s Magazine, Aperture PhotoBook Review, The New York Times, TIME Magazine Lightbox, and the San Francisco Chronicle. She is the recipient of a Fleishhacker Foundation grant, was a Critical Mass Top 50 Photographer, an artist in residence at the Banff Centre for the Arts as well as at Rayko, and was an affiliate artist at the Headlands Center for the Arts.

Littoral Drift

My work investigates our relationships to the landscape, the sublime, time, and impermanence, and the role that photography plays in shaping our experiences of these universal forces.

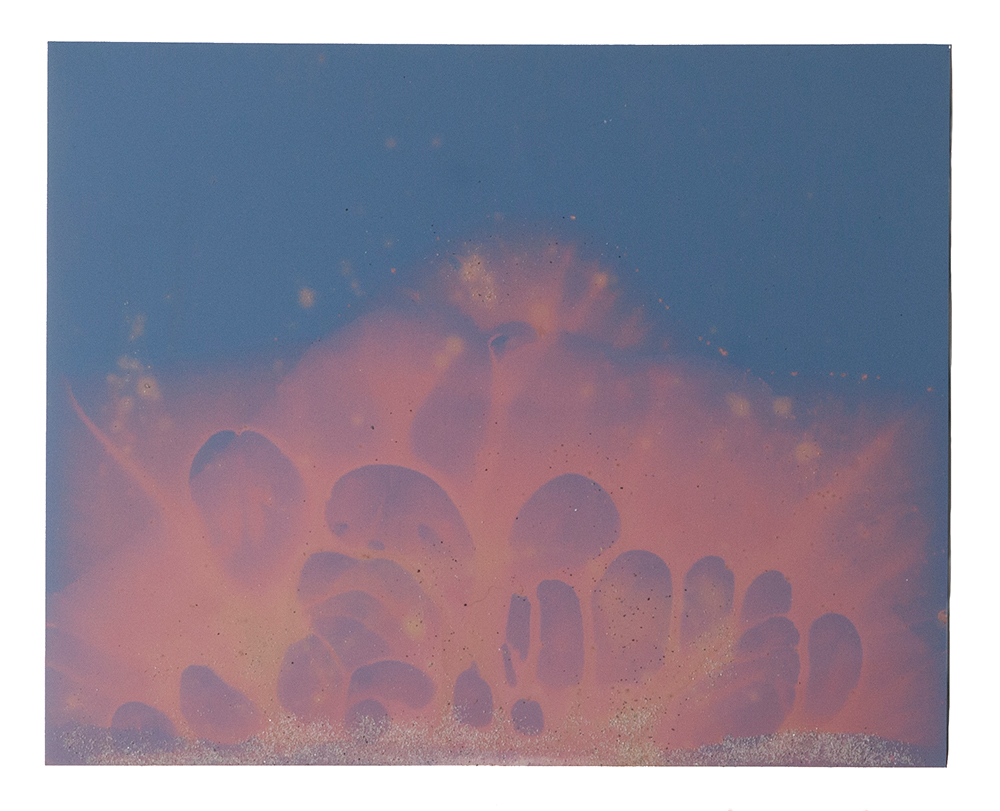

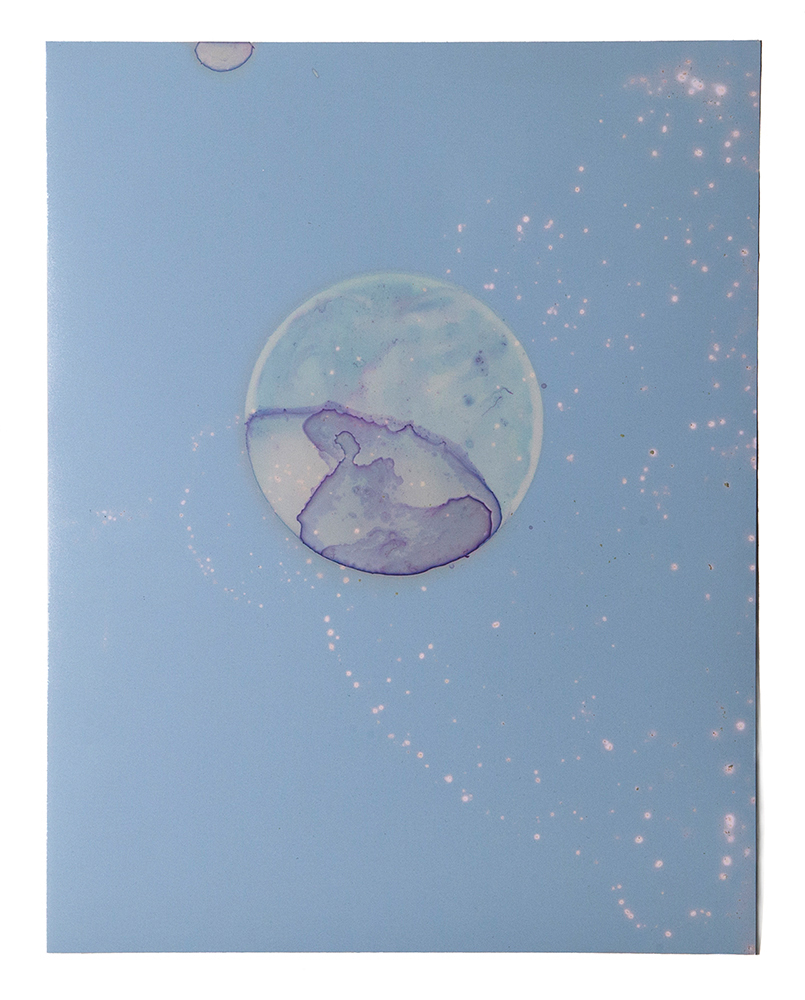

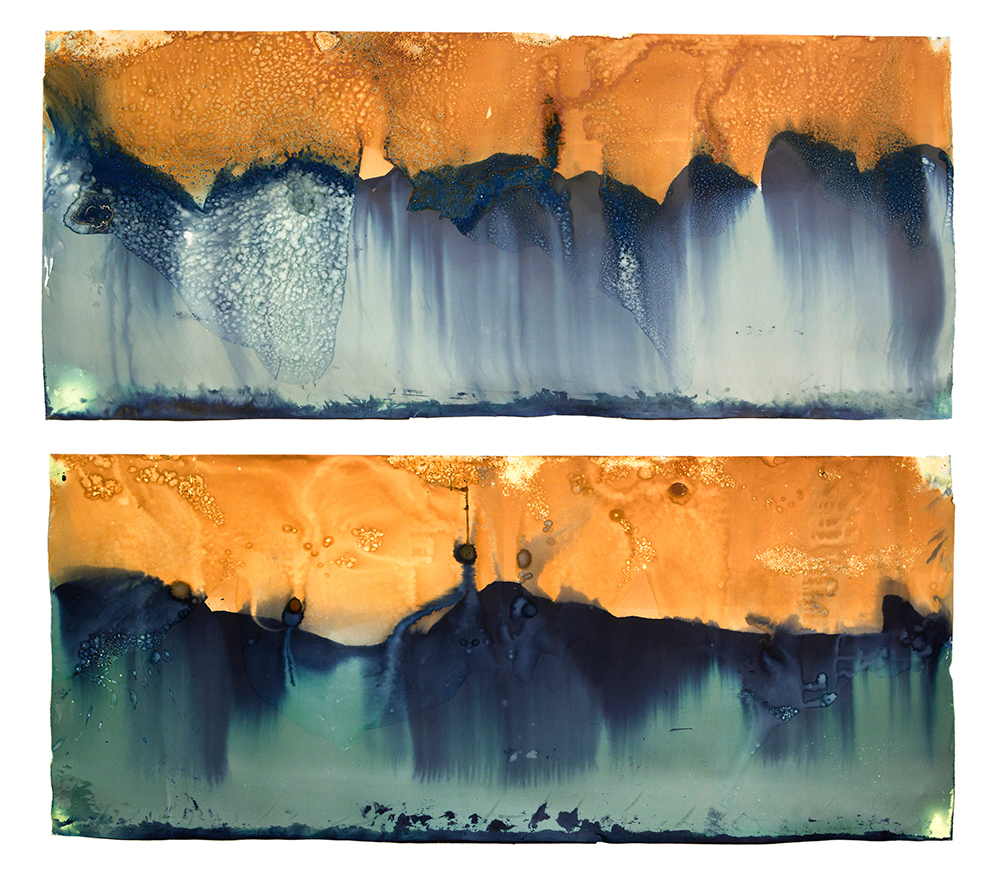

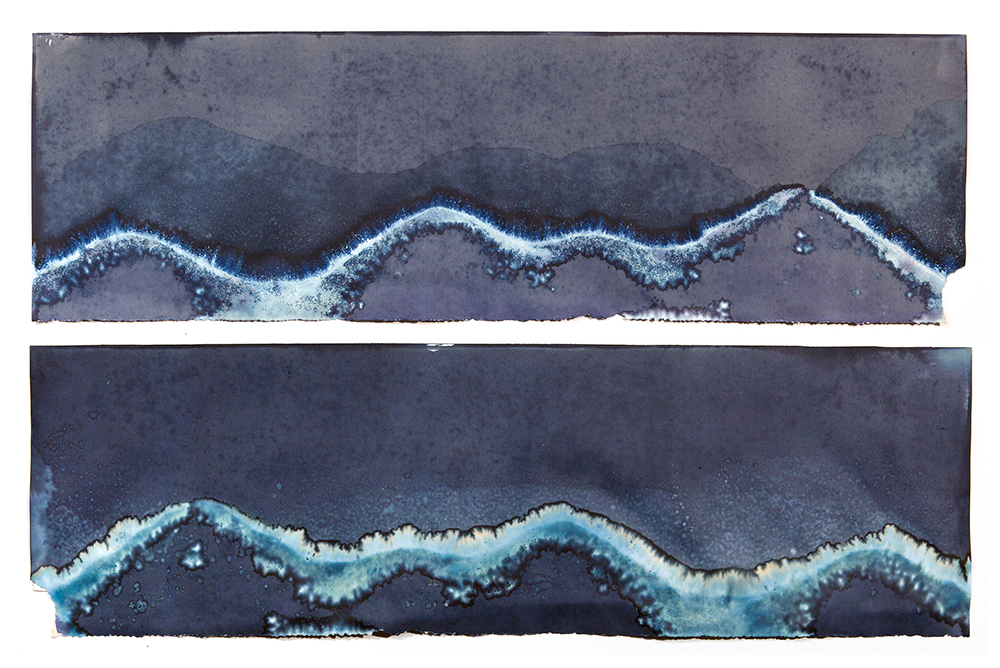

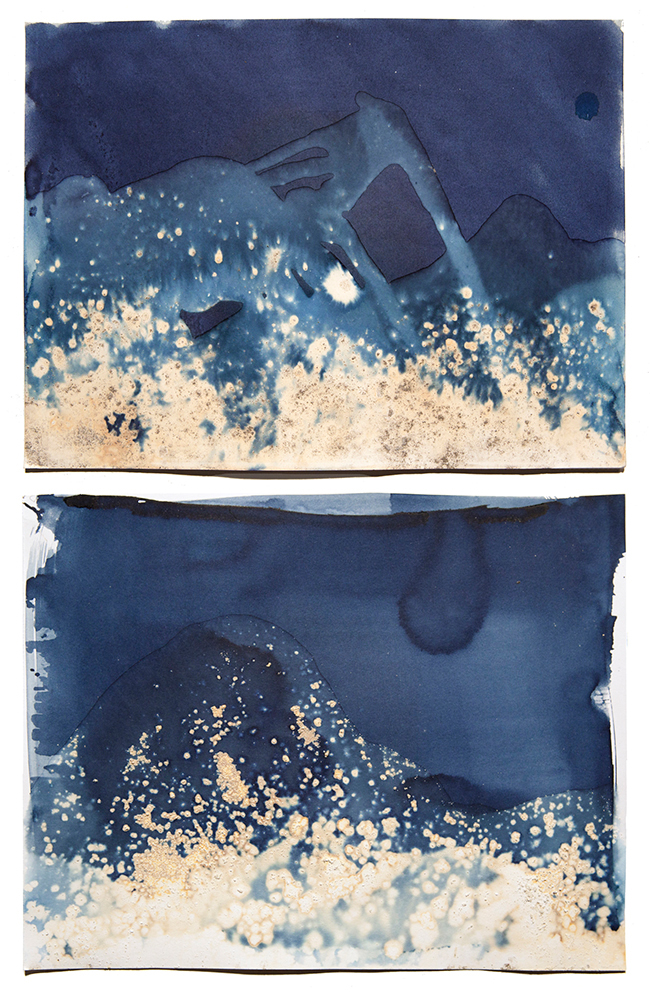

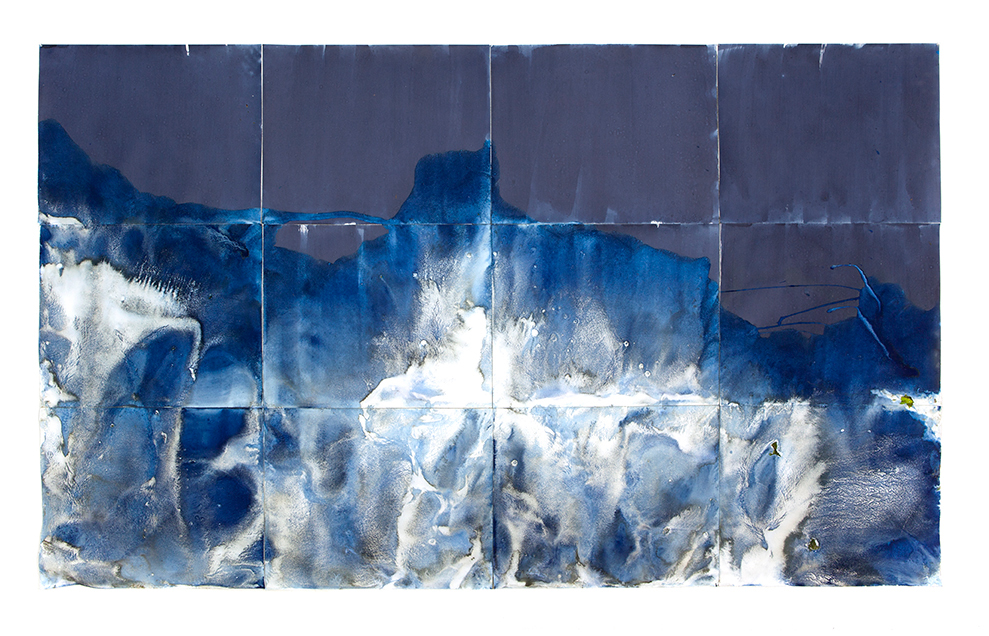

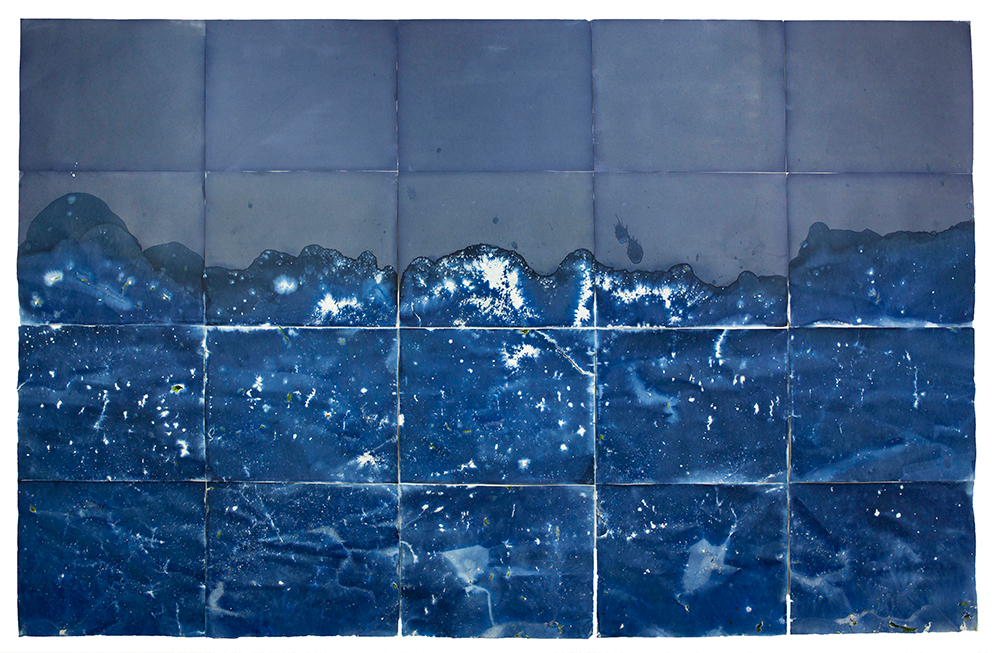

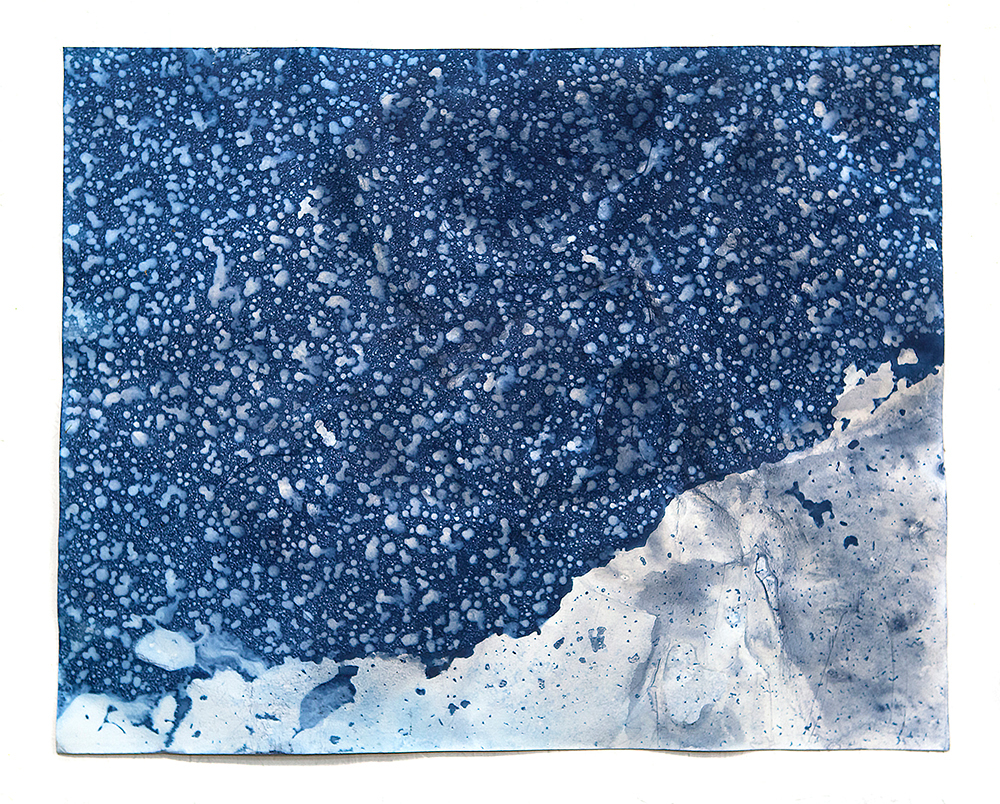

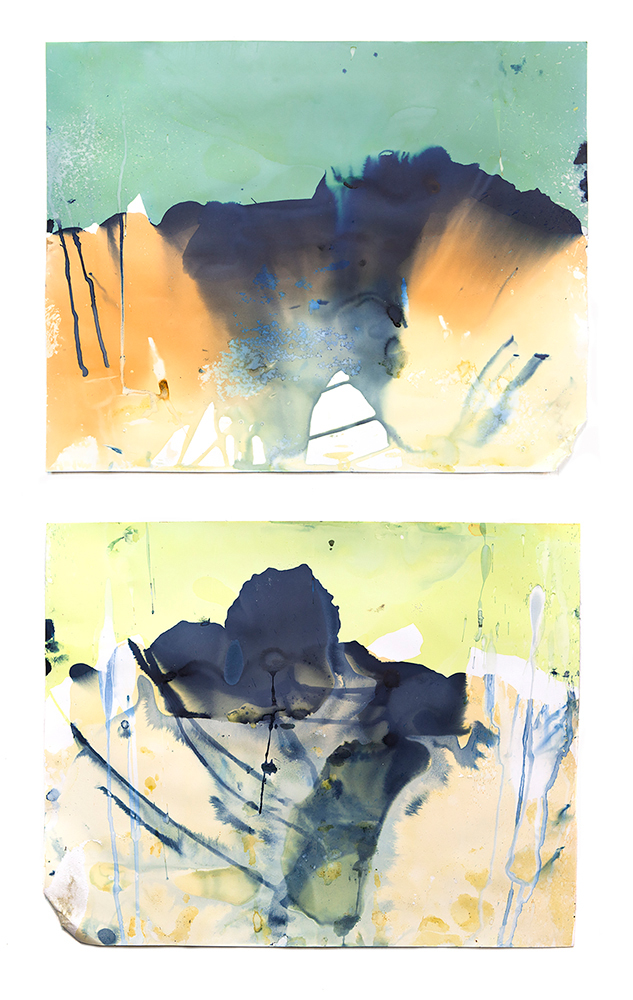

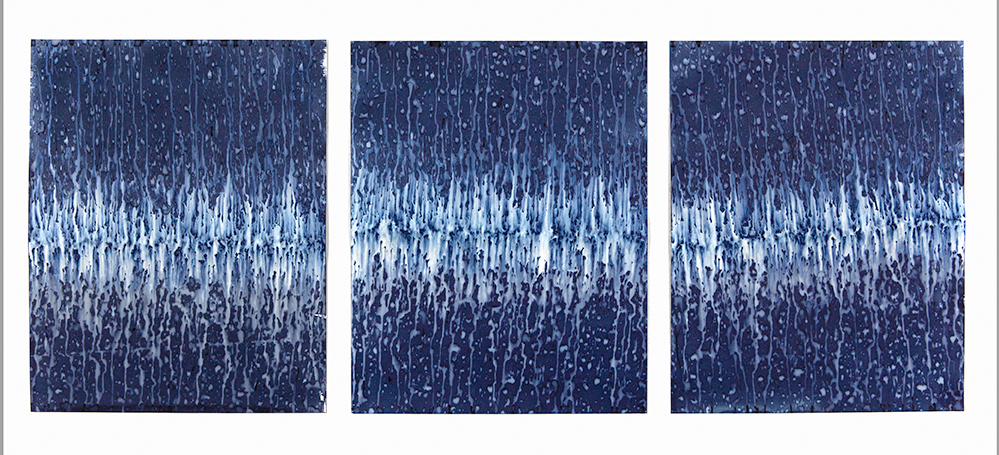

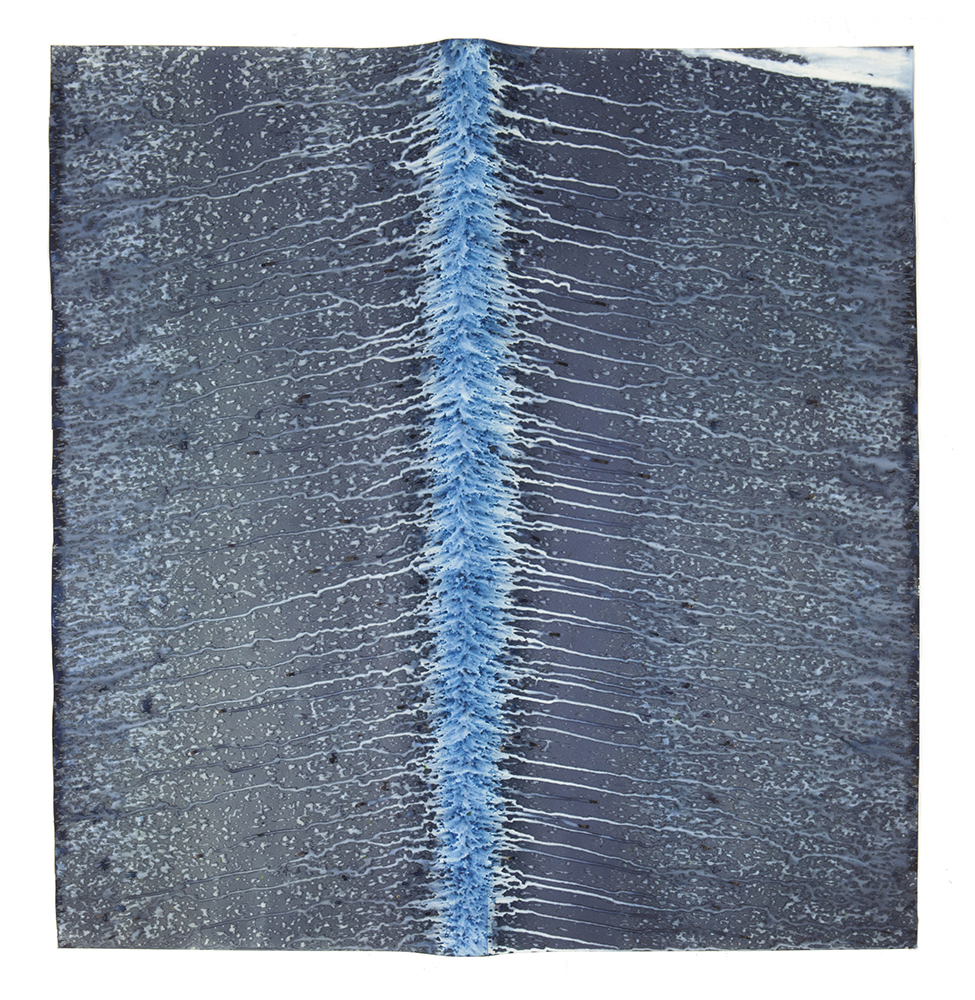

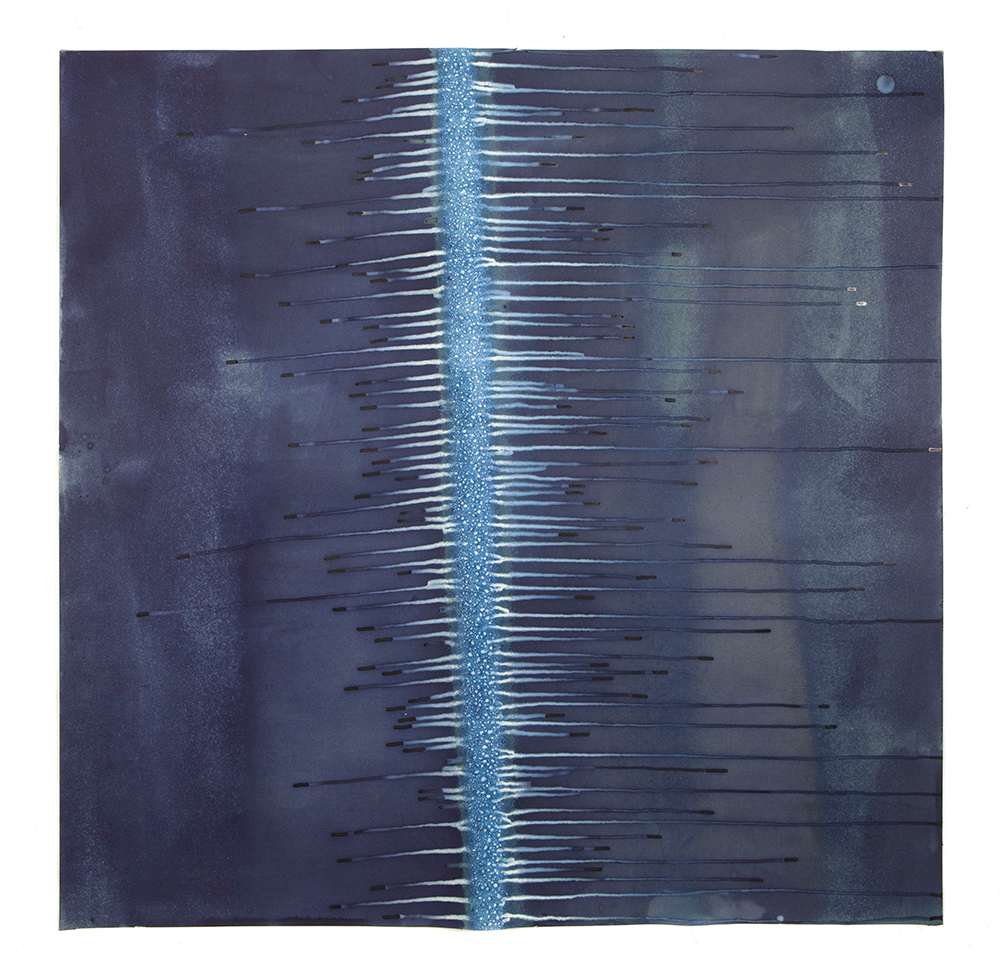

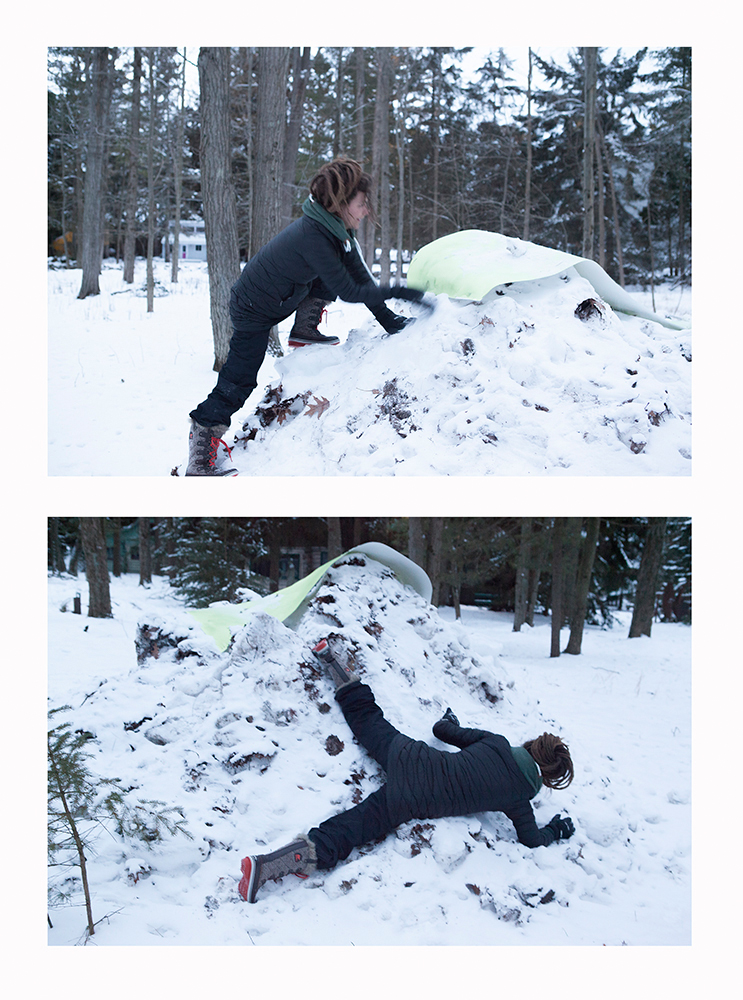

Entitled Littoral Drift, a geologic term describing the action of wind-driven waves transporting sand and gravel along a shoreline, the series consists of camera-less cyanotypes and chromogenic print made in collaboration with the landscape and the ocean, at the edges of both. The elements that I employ in the process—waves, wind, precipitation and sediment—leave physical inscriptions through direct contact with photographic materials.

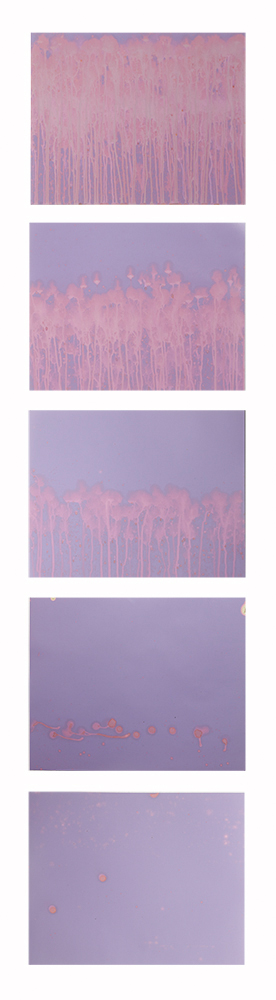

Photochemically, the pieces are never wholly processed; they will continue to respond to environments that they encounter over time. Cycles and dynamism are embedded in the work, as the pieces physically oscillate with daylight and darkness, grow salt, rust, and otherwise subtly drift in form. Each cyanotype is like a fingerprint of place, a hyper-literal, sometimes three-dimensional, photographic record of specific cumulative circumstances. Works are indexically titled with date, location, and details of the photographic paper’s interaction with the landscape. As part of the larger project, I selectively re-photograph moments in the evolution of the images, to generate a series of static records of a transitory process. Entitled Continua, the progressive images are shown as polyptychs.

Between the rapid pace of technological shifts in the medium of photography, and the sublime processes that shape our landscape over geologic time, the human condition is impermanent and full of enigmatic experiences. Perhaps where the fugitive images are analogies for a terrifyingly fleeting and beautiful existence, the process of re-photographing them is a metaphor for the incorporation and mediation of photography in the contemporary human experience.

Originally from Atlanta, GA, you’ve been on the West Coast for quite some time now. Did this begin with your MFA work at the San Francisco Art Institute where you are currently a visiting faculty member? What’s the predominant ideology of SFAI, and how do you feel your time (both studying and teaching) there has shaped your work?

I moved to the west coast as a response to the landscape. In undergrad, I drove from San Francisco to Arcata, CA with some friends and was wholeheartedly blown away by the landscape. I distinctly remember standing on Hwy 101 with redwoods to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west and knowing that I needed to really experience that region. After living in Arcata for about two years, I was admitted to the MFA program at SFAI.

One of the things that attracted me to SFAI was their pronounced interest in fostering experimentation and supporting a cross-disciplinary approach to art making. Before my MFA, I was a straight photographer, working in a color darkroom and making primarily environmental portraits. But I knew I needed freedom above all in my practice, and what I found at SFAI was a faculty that encouraged a broader set of considerations, pulling critical discourse from painting, sculpture, new genres, etc. and engaging in photographic concerns with a wide lens, so to speak.

Of course with this expansion in my thinking and seeing came lots of failed works, lots of failed attempts to communicate messy ideas. But some of my graduate professors reminded me that the process of making art includes all of the misses and all of the successful work, and that school is the perfect place to really push oneself into unknown territory. As a teacher, I try to bring that same enthusiasm for risk-taking to my students. I ask them about their secret ideas, the ones that seem scary and perhaps impossible, and then we talk through ways to realize these potentially hidden gems. In my own studio practice, I’m looking for that same intense inquiry, and the same drive for experimentation, and have ideas I learned at SFAI in my head every single time I’m working.

Your work exhibits a unique and exquisite color pallet. For those of us who are not intimately familiar with the cyanotype process, can you describe the physical processes responsible for these different colors?

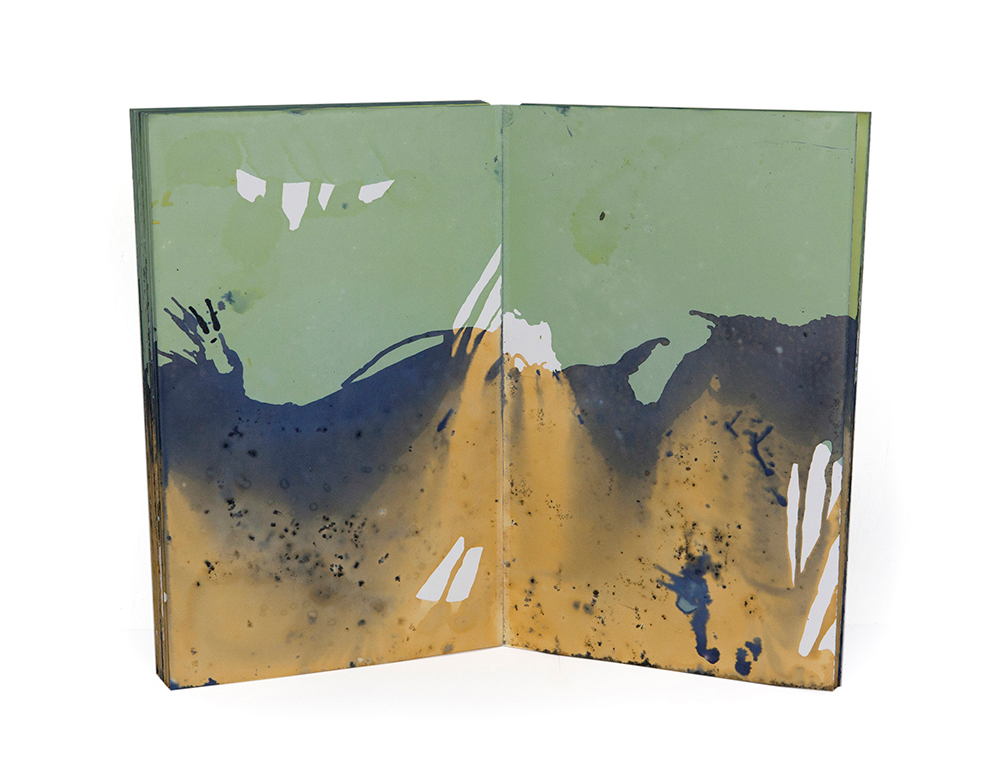

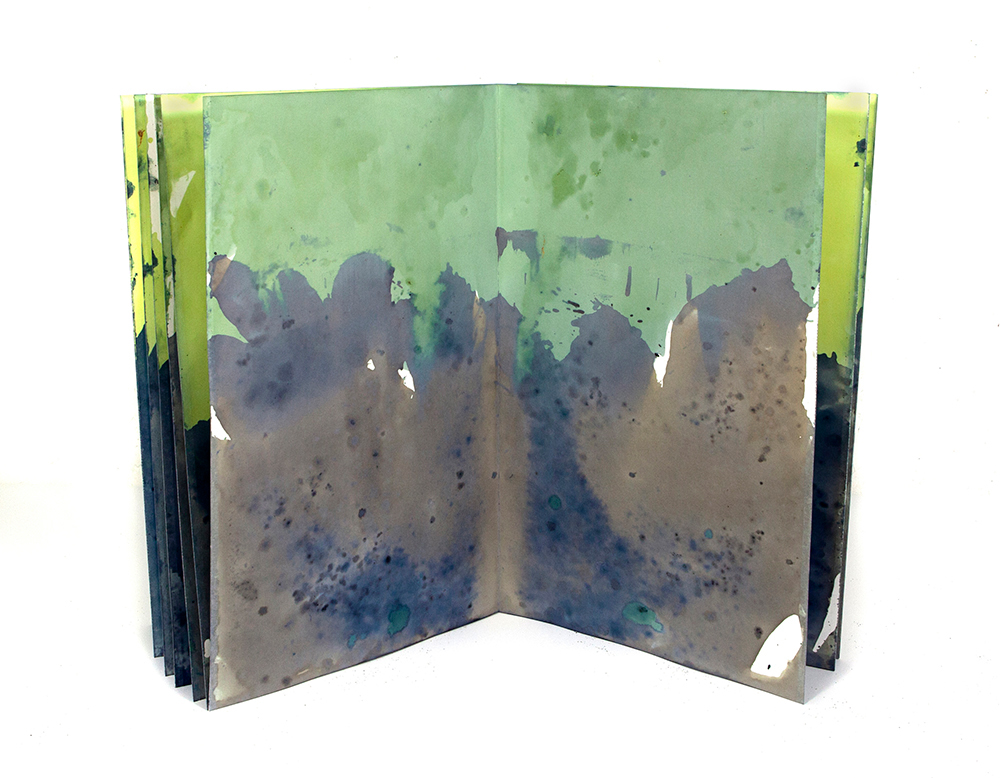

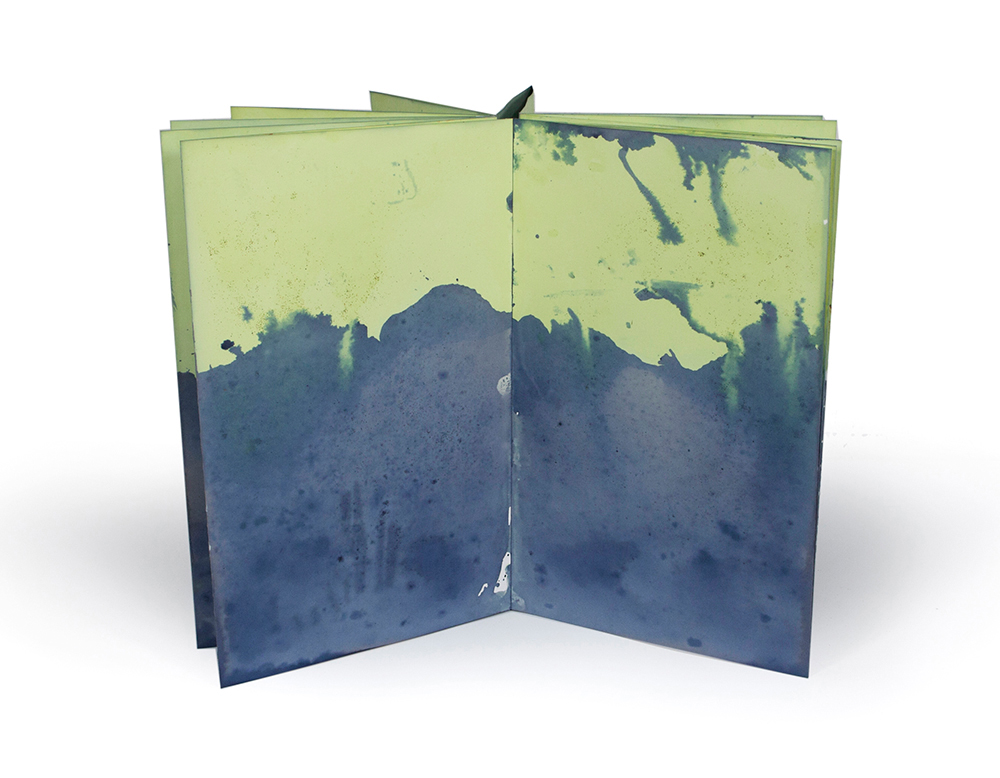

Cyanotypes typically result in a blue and white print, where the chemistry interacts with UV light and produces a Prussian Blue pigment. Because I’m not fully processing my prints, and because of elements from the landscape that the prints encounter, my palette includes rust, the white of salt growths, colors from residual debris, and dense layers of pigment. Also the pH of the water I encounter in the landscape shift the cyanotype’s palette. Sometimes I play with the chemistry to tweak the palette, and can achieve apocalyptic greens and golds. Because I intentionally leave my prints only partially photochemically processed, the colors can shift and change over time, depending on the environment where the print was made, and the environment where the print lives.

Also, regarding scale…to what extent do your materials dictate the dimensions of your work versus resulting from subject/artistic inspiration?

Scale is both limited by and inspired by, the place where I make. I love to make large work, but sometimes a quiet shoreline calls for small, more intimate piece. Also because I have to physically get the paper to a location, sometimes it is physically too demanding to lug the materials for large works into more remote sites. I usually bring a variety of sizes to each place, observe the movement of the water and the texture of the earth, and then intuitively place paper that I think will uniquely record the specific place and time that the work gets made.

Since its inception photography has often been thought of as a tool used to create “permanent” drawings of an ever-changing world. Of course, permanence and impermanence are tricky concepts, but you don’t fix your work, which means they will forever change and may even disappear at some point, is this correct? Why is this and how do you feel this positions your work in relation to photography’s history?

I’m thinking about time on the geologic scale. If one considers a large time scale, all art works, and indeed all things, are impermanent. Even our most dramatic human attempts toward permanence fail eventually over time, and usually succumb to the environment in some form. I think this issue is especially fun to kick around with photography, where there is a lot pressure for prints to be “archival”.

Photography is so tied to time, from the way we think about the length of an exposure, to ideas like the decisive moment, to asking prints to live beyond their material capacity, to the way the medium perpetually evolves with technological developments. Photography can collapse time in an interesting way in singular images, and photographic images, like all things, record time by their response to it. Fading, emulsion destruction, that famous yellowing that we’ve all seen when pulling pictures out of our grandparents’ attics…all of these are things speak to the way photography and time intertwine.

The earliest photographic images weren’t able to be fixed, and it was a huge advance in the field when early practitioners finally stabilized light-sensitive images. With my images, I wanted to heighten awareness of this time/image relationship, and so I only partially photo-chemically process my images. The result is that they oscillate in UV light and darkness, they have subtle shifts in form as chemistry and elements from the landscape continue to interact, and they are forever in a state of change. Conservators and cyanotype experts do not expect my images to totally disappear in our lifetime, but there is an unknown element regarding the work’s life over the long term.

Most cameraless photography tends to be non-figurative due to a lack of a lens which would traditionally focus a light refraction onto a variety of light-sensitive materials. Though very abstract, much of your work has a surprisingly figurative quality that seems to represent the specific landscape where it was made. Were you surprised by this at all? Does this feel like something you often embrace or work against in your image making?

In the early stages of this body of work, I was absolutely surprised by this uncanny resemblance of my images to the landscape in which they’re being made. I was making cyanotypes at the Headlands Center for the Arts and was shocked to see that the palette and shapes in the work actually looked like the landscape at Rodeo Beach, where I submerged the prints in the ocean. I see this kind of surprise as serendipitous, and it feels like some kind of gift from my collaborator, the landscape. So many times we struggle and work so hard, and occasionally we get a beautiful gift like this resemblance.

I always like to push back and play with the idea of my work being abstract. I was influenced by the way Walead Beshty talks about his work. He describes his work as concrete or literalist. And I’ve borrowed those terms to talk about mine, because really, these are not abstract at all, in that they’re not representing something that they’re not, or serving to suggest something other than what they are. They are actually photographs with physical inscriptions of the land that physically change over time. So their state and their aboutness are totally linked. But I can see what you’re speaking to, that formally they can be read as abstract. I think this is a sort of “and this, too” situation, where the work runs the line of both abstract and literal and doesn’t neatly land in one camp. I like that they’re messy in a way and hard to pin down into neatly organized camps.

I was lucky to see your show at San Francisco Camerawork (installation shots included), which I found to be completely stunning. Two of the biggest takeaways were your book installation and the sculptural qualities of your work. Would you be willing to share a bit about the book project you did during that show and describe the three dimensional presence/importance in your process?

Because time is so paramount in my work, I wanted to make a piece that had a relationship with exhibition duration. It is interesting to think about works in a show: they are there for a finite period, every viewer encounters them in a slightly different way, and they change during the space and time of an exhibition.

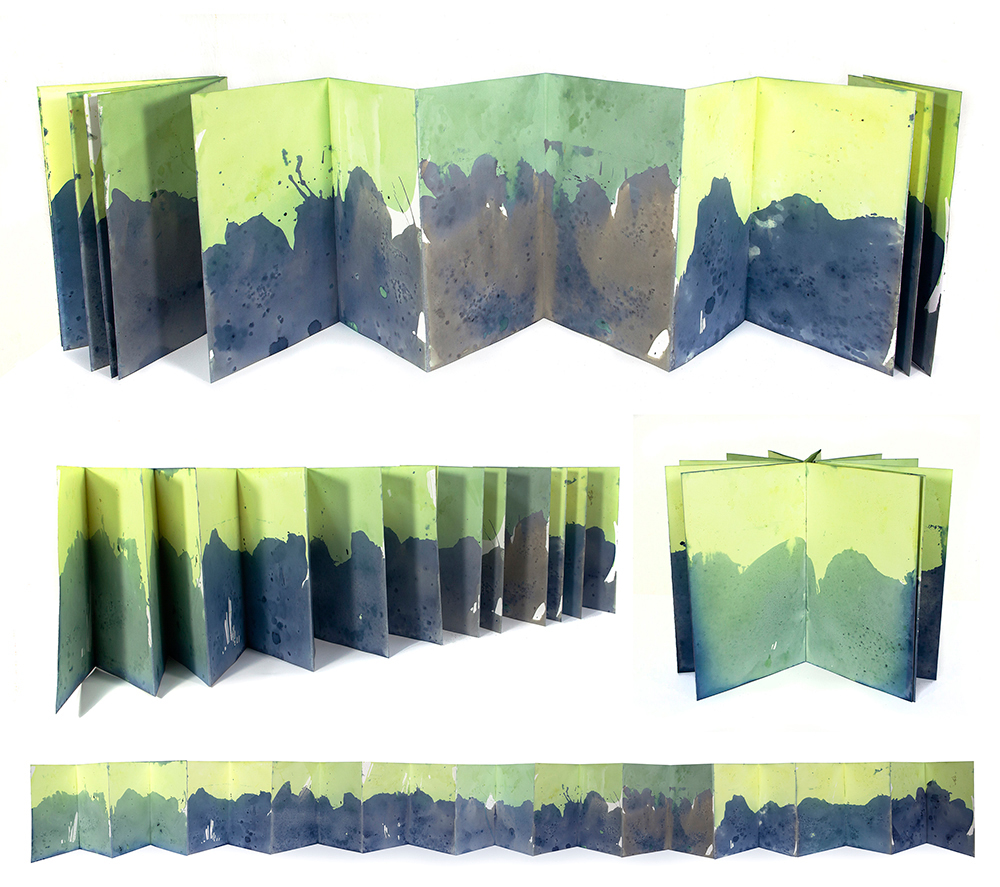

For SFC, I made a hand-bound accordion book, which is the first of three that I have since made. Each book has a page for each day of the corresponding exhibition. I treated the pages with cyanotype and elements from the landscape and hand-bound them into accordion books, but did not expose the books to light prior to the show. Upon opening the gallery each morning, the staff turned the page, revealing the next unexposed folio. As pages exposed throughout the day, staff photographed the changing image on a timeline derived from a Fibonacci sequence; the same sequence used to model the golden ratio and other forms echoed in nature and art. A time-lapse video of the entirety of the books exposing is forthcoming.

The books are records of days and weather and time. Some pages remain essentially unexposed, and may expose more over time each time a viewer opens a page. So they are initially exposed in the exhibition, but sort of weave together the exhibition space and their lives after that in cumulative exposure. I store them in the dark, but show them in studio visits and such, and so they are always subject to the light of their reveal. Books are inherently time-based, have a narrative potential, and have can be interesting sculpturally, so the book seemed to be the right fit for this idea.

Similarly, many of my works in the SFC show were two-sided or physically came off of the wall with 3-d properties. I’m interested in activating space. I like for these images to be an encounter, where the viewer can move around them much like one moves through the landscape. When I make two-sided works in the landscape, I’m fascinated at how different each side of the print is. An ephemeral tidal stream or river can run over the top of, and below, a cyanotype and make drastically different impressions on each side. And yet it is one piece, one moment experienced in two very different ways. That speaks to change, and how each encounter in the land, each specific set of circumstances, is always different, yet still connected on a continuum of time. The river is never the same from moment to moment, and my prints are direct records of that perpetually changing state.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025