Teun Hocks

A number of years ago, while visiting the Rodney Smith show at the Fahey Klein Gallery in Los Angeles, I was completely taken by the companion show of Dutch photographer, Tuen Hocks’ large scale hand painted photographs. As I was also working with hand painting, it was exciting to see work that was contemporary, yet rooted in tradition, and work that was quirky, yet compelling.

Last month, a fire in the PPOW gallery in Chelsea broke out, just as a Tuen Hocks’s work was about to go on exhibition. While most of the gallery was destroyed, Hocks’s photographs, drawings, and videos remained mostly intact. You have just a few days to check out the work at their new location at 511 West 25th Street, Room 301, through February 7th.

Art Info recently did a short interview with Tuen about his ideas and processes:

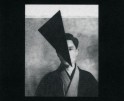

“For well over a quarter of a century, the Dutch photographer and painter Teun Hocks has been making his highly characteristic pictures: large-scale, single-figure studies of a middle-aged man caught in variously absurd circumstances.

Hocks plays this character himself, and the finished works seem to sit somewhere between newspaper cartoons and history painting. Aperture has recently published a monograph on Hocks’ work, with an essay by Janet Koplos. When Hocks visited the Aperture Foundation in New York to give a talk, he took a few minutes to speak with ArtInfo.

Teun, let me ask you about this character that you portray in your pictures. He’s nervous, somewhat self-obsessed, and his attention is always in slightly the wrong place. Is that you?

No, I’m quite different than that. Of course he comes partly from me, but these are not self-portraits at all, and I’m glad about that because I hope that I’m smarter than he is. But I’m not even sure that he’s always the same person. Sometimes he’s more afraid, and sometimes he’s more self-assured. Sometimes he’s too sure of himself, such as when he thinks he can shoot stars down. That’s one of my favorites.

Still, anyone looking at your pictures could imagine themselves in these kind of situations.

That’s what I hope happens. But if it’s that man on the ice floe, well, that’s not very good! Or consider the man with his head in the picture frame. He has a curiosity that’s not normal. He can’t control it. But I wanted to take the idea of looking at art literally, so that you really want to get in—and to feel it.

That picture-frame photograph strikes me as particularly apt because in practical terms, you are actually in your pictures, aren’t you?

Yes. There’s a big backdrop that I paint or build, or whatever’s needed, and I stand in the middle of that. Then I take a picture of myself in black and white and enlarge it. I do it myself in the darkroom with a little bit of help. Then I tone the picture sepia. And later I add oil paint. I color everything, but it’s transparent, so that you can see the picture underneath.

It’s a peculiar way of working. Why do you think it’s evolved like this?

Maybe it’s a way to have everything under control, for me to be able to get exactly what’s in my head. Or at least to come close.

So, when you’re taking the photographs, how many people are there with you?

Usually nobody. I have a timer on the camera and a remote shutter release which I throw to one side after I’ve pressed it. Then I have to wait a few seconds and the camera clicks. That’s normally how I work, but sometimes I am so caught up in middle of everything that I need help in releasing the shutter. Sometimes that might be a friend who happens to pass by, or my wife, or my son. Anybody can do it.

But ideally you do it yourself.

It’s true that I want to do everything myself because it’s my work. I’m never really satisfied when I let somebody else do something.

Tell me how you invent these absurd situations. I know that you use drawing a lot.

Sometimes I have an idea immediately, but most of the time I have half-ideas. So I make sketches. Sometimes I’ll look in my sketchbooks and find a drawing that I’d almost forgotten about. So I change something, and then I find I’ve started to make a work. I make a choice that I want to make a drawing into a work if I find I’m intrigued myself. But I need to draw. I have to draw to think.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Sirkhane DarkroomMarch 26th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024

-

European Week: Steffen DiemerMarch 6th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024