Bryan David Griffith

Looking at photographers from Review LA…

“I make fewer than 50 photographs a year. For every exposure I make, I spend many more days in the field just observing, waiting for that rare moment when season, time, and weather add up to just the right light. My work is about slowing down and noticing beauty in the world, especially that which is in danger of being lost or taken for granted. My work is less about a subject and more about a way of seeing that subject, less about a landscape and more about a feeling of being in that landscape.”

This is quite a statement by Bryan David Griffith, and in this digital age, a rare one. He’s a photographer who likes to change up his photo explorations, whether it be subject matter or camera. And it’s the idea of exploring contradictory ideas simultaneously that allows his creative energies to flourish. Bryan lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, and after a career in business consulting, gave it up to become an independent artist. This practice means he drives across the country several times a year to sell his photographs at the nation’s top juried art fairs and festivals. In July, Bryan will exhibit a solo show at Open Shutter Gallery in Durango, CO July 8-Sept 15 and he currently has work on view at the Translations Gallery in Denver.

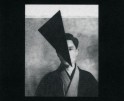

I am sharing two bodies of work that are quite disparate. In a Big World Wandering has a pictorialist style, stripping down the world in front of him to black and white elements. I’m trying to get straight at the core of my life as an artist, primitive equipment and techniques. The images explore my core memories, emotions, values, and choices, but I try to make them as ambiguous and timeless as possible, so people can bring their own narratives to the images.

Another Man’s Treasure was created with a view camera in less-than-ideal conditions, producing abstractions in the way a color-field painter might develop a canvas, or an architect might divide a space.

I try to make photographs that seem remembered, retold, or dreamed, rather than documented. I write a curious line from the middle of a story, soak it in mystery, and ask you to complete the rest. The situations are universal metaphors. The subjects are ourselves, and those we love. I don’t intend to show you something new, but to conjure up unexpectedly what you’ve deep

down always known.

We are often alone in a big world wandering, our destination unclear in a place that’s ambiguous and often absurd. Yet beauty and inspiration also fill that same world, and it’s up to us to accept ambiguity with wit and whimsy, rather than despair. It’s up to us to open our eyes wide, to grab life with both hands and find the wonder in it. Our characters are ultimately defined not by the destinations we reach, but by the choices we make along the way. Thus the figures in my photos are often in the act of making or contemplating such a choice. And I’m ultimately just another person with a camera, inspired by dreams, trying to preserve memories.

I make these images in my own wanderings, in my own odd, anachronistic, and impractical way. I photograph without electronics using large and medium format camera bodies outfitted with homemade lenses that I’ve cobbled together from vintage optical components. The images, along with the blur, diffusion and other effects, are captured in camera on film. I then make platinum–palladium prints onto handmade Japanese paper. This 19th century method is among the most permanent and costly photographic processes, yet yields a delicate translucent print with a unique ephemeral, dreamy quality that complements the images.

Another Man’s Treasure began as a challenge to see beauty in ugliness: to find

worth in the discarded or left behind. I wanted to slow down and appreciate

the ordinary. In my travels for my work as a large-format landscape

photographer, I often encountered the prevalent abandoned cars, junk

collections, derelict structures, and railroad equipment strewn throughout the

American West. While such sights were eyesores to me as a nature

photographer, I tried to see them anew with the eyes of an abstract painter,

and to photograph them with the same methods and intensity I use to

photograph a landscape, curious to see what would result.

Soon I began to hear stories and see patterns in the rust. My subjects were

mass-produced, but time had since transformed them from identical to

individual characters. The unique patina that distinguishes one rusted car from

another of the same model is a record of events witnessed and human lives

encountered during the intervening years. Like an archeologist who seeks out

the refuse heaps of an ancient society to learn about their way of life, I started

to see my subjects as relics of twentieth-century America, being slowly

entombed in dust. I try to imagine what future archeologists will conclude

about us from what we’ve left behind

I photograph these found compositions with an “old-fashioned” large-format

view camera using natural light. This camera has no electronics and is much

more difficult to use than a 35mm or digital camera, but in skilled hands it

produces images of much higher quality and fidelity. I use modern films and

print on Fuji emulsions processed and presented to archival standards. I believe

this process results in the best print possible, accurately reproducing the vibrant

colors in the film without compromising the smooth, subtle tones. I continue to

rely on creative vision, practice, patience, and luck to make my work; not special

filters, digital effects, or other gimmicks

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers, Dennis DeHart in conversation with Laura PlagemanApril 16th, 2024

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024

-

European Week: Jaume LlorensMarch 7th, 2024