Leah Beeferman: The States Project: New York

Leah Beeferman is a conceptual artist, using photography in her newest digital work, Strong Force (Chromodynamics). Even with a history of using photography and the photographic image in her work, she does not consider herself to be a photographer in the traditional sense. In this series, Beeferman explores the ways in which we perceive and observe our surroundings through the use of photographic imagery, scans of objects, drawing, and collage. By positioning all of these different elements together in a single plane, and skewing the traditional rectangular contour of a photograph, the typical meaning of perception of space and time through photography as we have grown to know it has been removed. Below are a few questions that I asked her about these fascinating most recent works.

Leah Beeferman, based in Brooklyn, works with digital drawing and sound. Her visual work integrates digital drawing practices with photographic material, laser-etching, or specific software. Her sound work combines field recordings and digitally-created sound to create invisible, abstract narratives. She has participated in residencies in Iceland, Finland, the Arctic Circle, Chicago, and New York. Recently, she has shown work at Klaus von Nichtssagend, NY; Essex Flowers, NY; Fridman Gallery, NY; Ditch Projects, OR; and Interstate Projects, Brooklyn. She also co-runs Parallelograms, an ongoing online artist project.

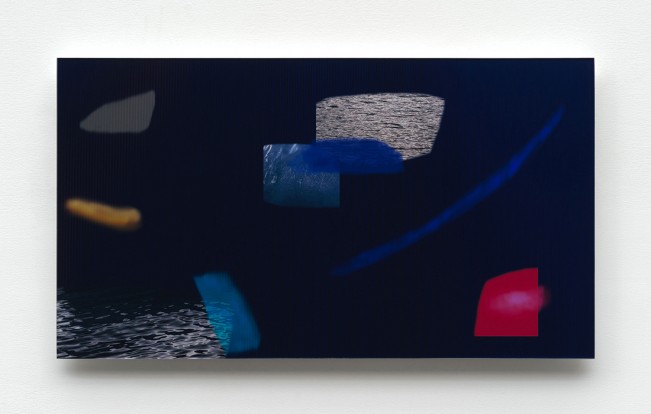

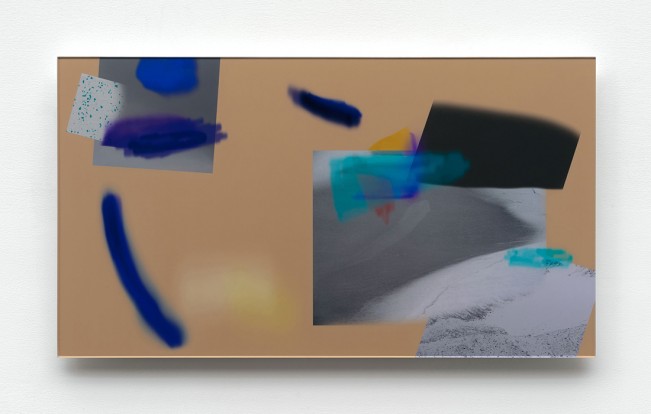

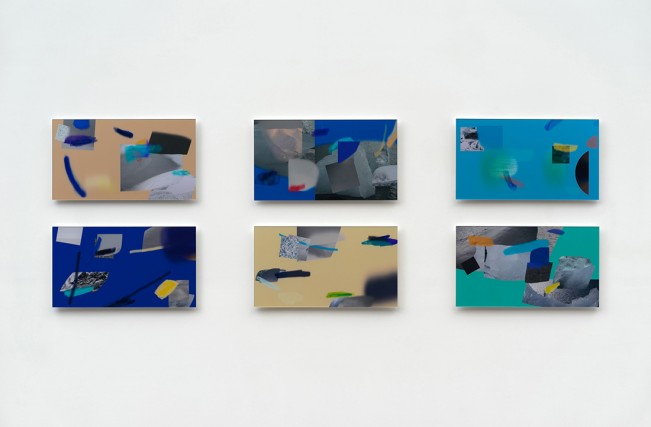

Strong Force (Chromodynamics)

I make abstract digital drawings, videos, laser etchings, and sound pieces: distinct processes linked by interconnected forms and ideas. These works contribute to a larger, ongoing study of digital drawing which seeks to generate spaces of flatness and infinite depth by merging a very “real” space from my own observation and experience, the intangible and nonvisual space of theoretical physics, and computer-based image-making.

In your series, Strong Force (Chromodynamics), the title referring to theoretical quantum theory of the relationship of elements that compose the most basic building blocks of our existence, protons, neutrons, and pions, you seem to be examining the most basic building blocks of our digital imaging tools. You composite and collage photographs with raw basic uses of digital tools such as the brush tool. Through this are you then examining the basic materiality of our digital visual tools? How do you see this then subsequently extending into an exploration of the ways in which we consume media and imagery?

Just to clarify, the basic building blocks that Chromodynamics refers to are actually the interactions between quarks, which make up protons and neutrons. But, I love your idea of thinking about “building blocks” in relationship to the basic materiality of digital visual tools.

I have thought a lot about the relationships between the ‘systems’ of my visual language and the systems of understanding/functioning that quantum physics represents. In that way, physics is more of a reference point for abstraction rather than something I am seeking to illustrate or more specifically communicate.

I am interested in the experiences of perception and observation. In this work, putting the abstracted photographic images on the same ‘plane’ as the drawn marks turns images into drawings, and photographic ‘real’ into an abstraction. I like to think about how we process imagery and what we see in the world — how observation and imagination conflate to become a third, unique element. And, thus, how observation really is not objective.

But you ask about examining the materiality of our digital tools, and I want to try and address that more specifically. I certainly am interested in the relationships between the ‘digital’ and the ‘real’, and where the two realms come together. I want the process of making these pieces to mirror my experience of looking and thinking: totally intuitive, and not dealing with a process step in-between. I am using the computer as a very basic drawing tool — just expanding “drawing” away from “pencil on paper” or “ink on paper” (I have worked quite a bit with both), and into a less traditionally material realm. But I don’t think about the use of the computer as a drawing tool being any different than these traditional modes. I am focused on being impacted by something and wanting to “draw it” — whether it’s reading about quantum physics, or experiencing the Arctic/northern wilderness. I want to create complex, visual, psychological, and emotional experiences by composing these few elements interacting in a particular way, and I’ve found that these digitally-created and digitally-produced pieces happen to do that better than the hand-drawn ones.

In terms of a broader consumption of imagery and media: I think a lot about which things I make should remain digital, and which should get produced as prints or objects. The Strong Force pieces are much different and more impactful in person because their surfaces are very specific (printed on high-gloss metallic paper) and the object/non-objectness of them is very important to their content. So, though I make the images digitally, it is important for them to exist and be experienced in real life. I’m wary of how much of what we experience is both digital and based on common cultural references, and I think I really wanted to make work that gets my viewers to feel something — not immediately go to something outside of themselves as the main point of connection.

How do you situate yourself in the world of photographic image making? Would you ever consider yourself a photographer? How exactly do you define yourself? I ask this because predominantly the artists that I am featuring in the States Project:NY blend the boundaries.

A lot of my current work is engaged with the world of photographic image-making, and I’m grateful for it – I’m excited about the conversations happening there, and about participating in them. Though I would not define myself as a “photographer” in any traditional sense, I have been making work that has been lumped in with photography for years – whether it had some abstract laser etchings on plexiglass (imaged below) included in a show at the Camera Club of New York in 2013, or having prints and drawings in a show which was part of the New York Photo Festival in 2012.

It has taken me a long time to fully understand my relationship with photography; there certainly has been a strong one despite that fact that for many years I wasn’t using any actual photographic imagery in my work. I finally started to be able to really articulate that relationship somewhat recently, after reading the “Curiosity” issue of Aperture magazine — a really fantastic issue. In it, there was discussion about the camera as an interface between the world and the artist, which paralleled my use of other technologies (the laser cutter, microphones, the scanner) as direct technological interfaces between what I was seeing, hearing, or reading about, and what I was making. My experience making work suddenly felt very much akin to that of photographers: “here’s something in the world” and “here’s what I’m making with it,” translated through a very direct and immediate technological interface. The magazine also presented issues about objectivity and observation in a great interview with Peter Galison (a historian of science). That issue of Aperture was really exciting for me, because it brought all of my interests kind of in direct conversation with photography, and suddenly my relationship to photography was so much more clear.

Like I said before, I always want my translation from observation or idea to artwork to be non-intrusive and based on intuition, and for the past 10 years or so, that translation was conceptualized around the idea of drawing. I still consider myself a drawing-based artist, but my definition of drawing is and has always been, very broad. And through thinking about these issues, working with photographic imagery, and having in-depth conversations with artists who have similar concerns (such as Lucas Blalock in our upcoming interview on Bomb’s website), I have honestly come to think about drawing and photography as being, in many ways, functionally the same! So I won’t call myself a photographer, but I think I engage in a very similar mode of thinking that a lot of photographers do.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026