Ken Weingart interviews Arne Svenson

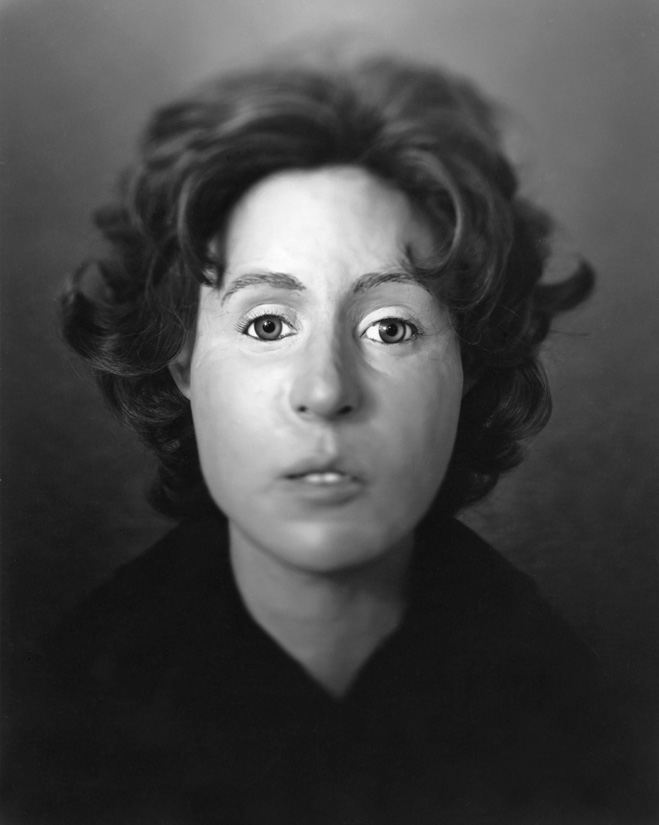

Some years ago, I stood in the Western Project Gallery in Los Angeles surrounded by large haunting images of faces. They were human, but not quite, and I felt a chill go down my neck as I processed what I was looking at. I had read about the exhibition and was intrigued, especially after becoming a fan of Arne Svenson’s sock monkey work. But his project Unspeaking Likeness was very different and chillingly fascinating. As a photographic artist, Arne’s “work revolves around the concept of reanimation and resuscitation – the breathing of life back into the moribund or forgotten.” Each time he steps up to the photographic plate, he is examining a different subject.

Today, I am sharing an interview that photographer and blogger, Ken Weingart conducted with Arne Svenson. Ken has been producing interviews for his Art and Photography blog and he has kindly offered to share a few with the Lenscratch audience over the next few months.

Arne Svenson is a well-known fine art photographer who is currently represented by the Julie Saul Gallery in New York and Western Project in Los Angeles. For his last exhibition, Arne experienced quite a controversy recently when he was sued by one of his subjects for his series The Neighbors, after they learned that he photographed them without their knowledge with a telephoto lens from his apartment. The news made worldwide headlines, but Svenson won the case in August 2013 (the subject is currently appealing the ruling). Many viewed the outcome as a victory for creative artistic rights (PDN story about The Neighbors Controversy). I spoke with Arne recently about this and other aspects of his innovative viewpoints on life and art. His new exhibition Workers is due out in a few weeks.

How did your art career start, and was it always photography centered?

My art career more or less snuck up and grabbed me unawares. I was working in my former field, special education, when someone gave me a camera and I began taking rudimentary staged photos. Eventually, my obsession with the work overtook the practical, clear-headed side of my life and chased me to NYC and a life in the arts.

How did you like growing up in Northern California?

I grew up in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. I came of age during the time of hippies and as a teenager would sneak out of the suburbs and head straight for Haight Ashbury, the counter-culture epicenter. As I grew out of that life I found San Francisco had no hold on me and I immigrated to New York City, where I have been for over three decades.

Why New York?

I visited NYC for a week in my early 20’s and became enamored, terrified, and challenged by it. When I returned to San Francisco it was as if all the color had washed out of the city, and I moved to New York a year later. Unlike any other city, NYC resonates with a palpable pulse, a life running through the streets that, for whatever reason, attracts and enables me to access my creativity more readily. I never photograph on the streets of NYC, but more valuably use it as a lifeline to vitality in my work. And no matter how much it changes, it still has a seething quality that I love and respect.

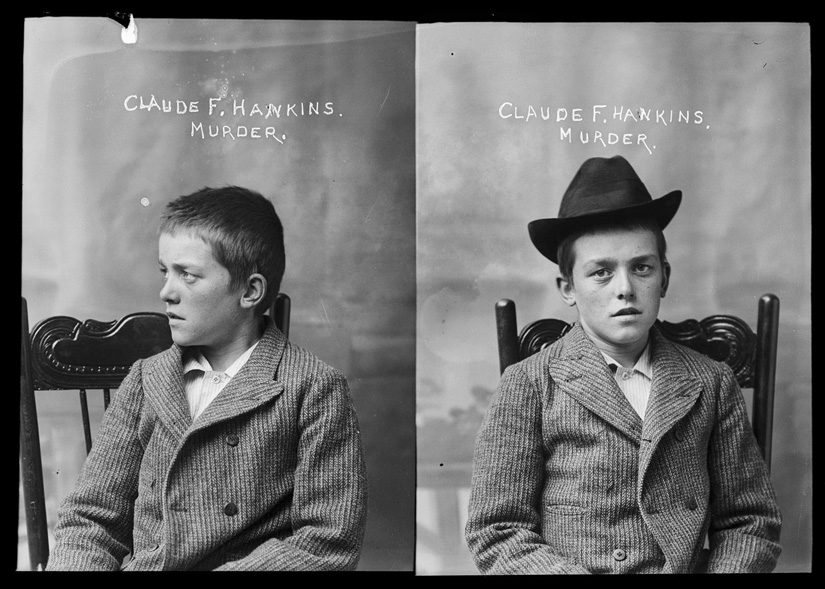

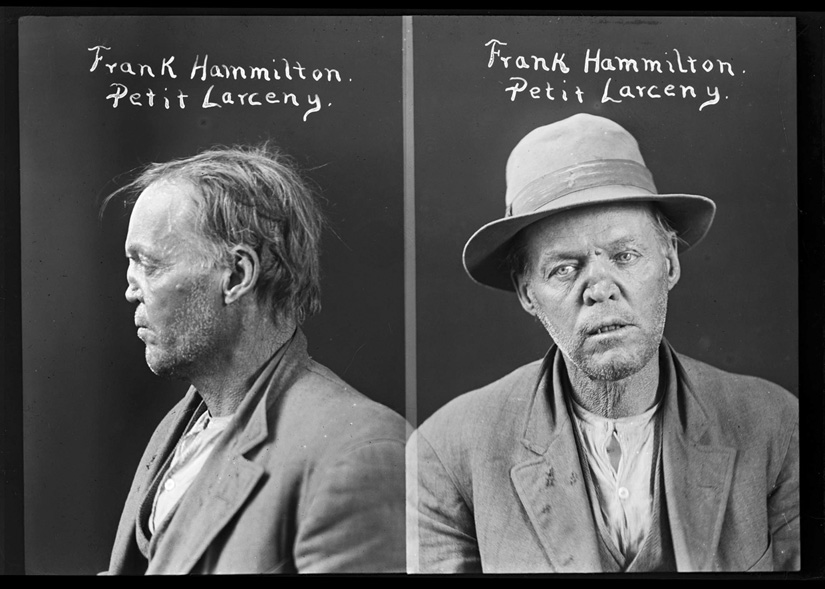

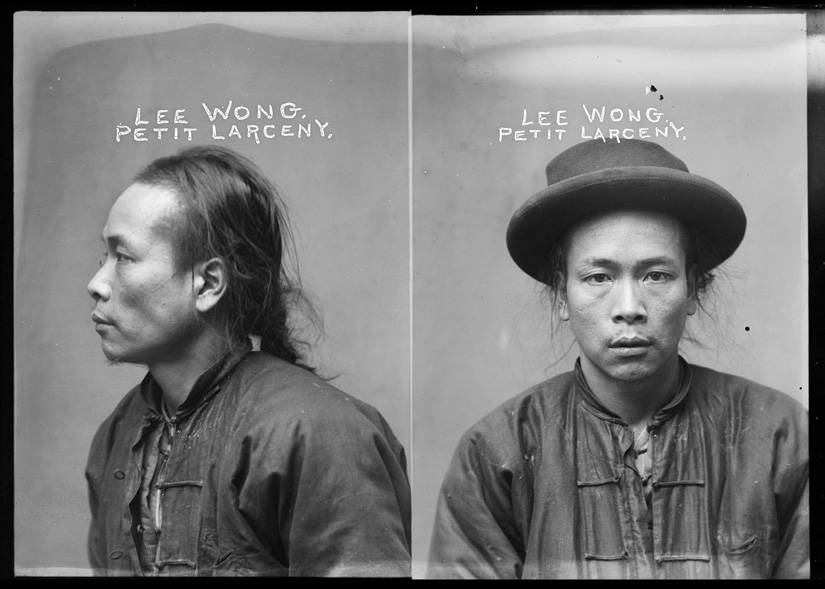

Your series Prisoners is fascinating; tell us about it in a nutshell. What intrigued you most about the prisoners?

While in a California antique store I discovered a cache of early 20th century glass negatives, 500 of which were mug shots picturing front and side views of newly arrested men. In each case, the man’s name and suspected crime was etched into the glass above the subject’s image. I printed the negatives and then spent two years researching the lives of the men pictured, creating the book, Prisoners.

The mug shots were atypical in that they were taken by a small town photographer, Clara Smith, who used her studio – with its pastoral painted backdrops – as the setting, and shot the images with racking daylight. This gave the images a compelling, naturalistic, almost classical feeling that revealed more about the man pictured than a standard mug shot would ever provide.

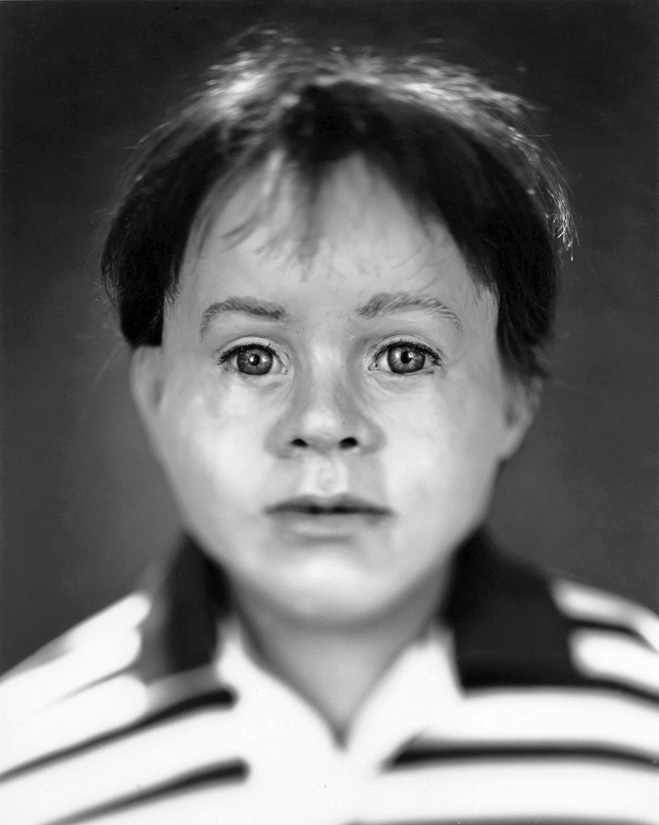

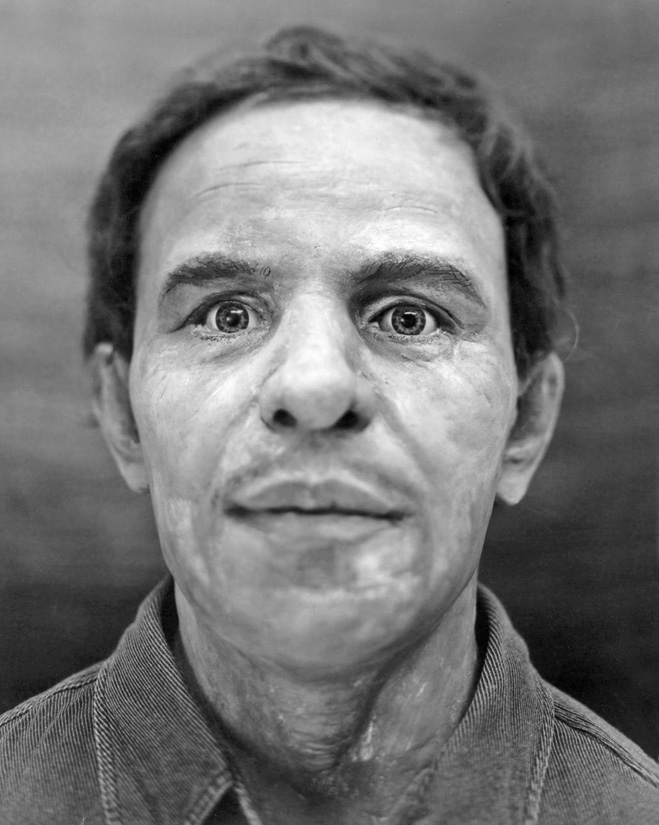

In Unspeaking Likeness, you photograph forensic facial reconstruction sculptures. How did this idea come about and what did you learn from it? What were some of the more interesting stories behind the heads?

I was photographing medical specimens at the Mutter Museum (Philadelphia) when, in a storage room, I came across a sculpture of the disembodied head of a young woman, wearing a wig and a pair of oversize 1970’s eyeglasses. I learned this was a forensic facial reconstruction sculpture and, intrigued, began an international search for more examples of this art to photograph. Much of my work revolves around the concept of reanimation and resuscitation – the breathing of life back into the moribund or forgotten. The forensic reconstructions were the perfect subjects to satisfy this criteria; a person lives and dies, the soft tissue, thereby the physical identity, disintegrates, the skull is found and, finally, a face is rebuilt – an imperfect path to a form of resurrection.

The vast majority of reconstructions I photographed were of people who had been murdered and their stories are harrowing, i.e. a woman is last seen pacing on a hilltop alone, smoke begins billowing out of a grove of trees and later her body is found burned beyond recognition. Or a child’s skeleton, clothed in a jean jacket with a ladybug brooch pined to the lapel, is found laying behind bushes on a golf course, hidden in plain sight from the golfers for a number of years.

How did The Neighbors idea come to you? Who did you shoot and why? What were you trying to discover or say?

I shot for the tiny nuances of gesture and posture that define who we are, collectively. The subjects are to be seen as representations of humankind, non-identifiable as the actual people photographed. I was also intrigued by the way light struck the building/glass, how it diffused and flattened the subjects within, giving the photographs a unique palette and an almost painterly presence.

There was some controversy; were you surprised by that?

Yes.

The lawsuits over The Neighbors must have caused a lot of grief. Would you count that as one of the worst experiences you have ever had to go through, or was it not as bad as we might imagine?

Of course any lawsuit is stressful, but one that challenges artist’s rights is more so because the consequences reach past the individuals involved and (can) directly affect the lives and art of all creative people.

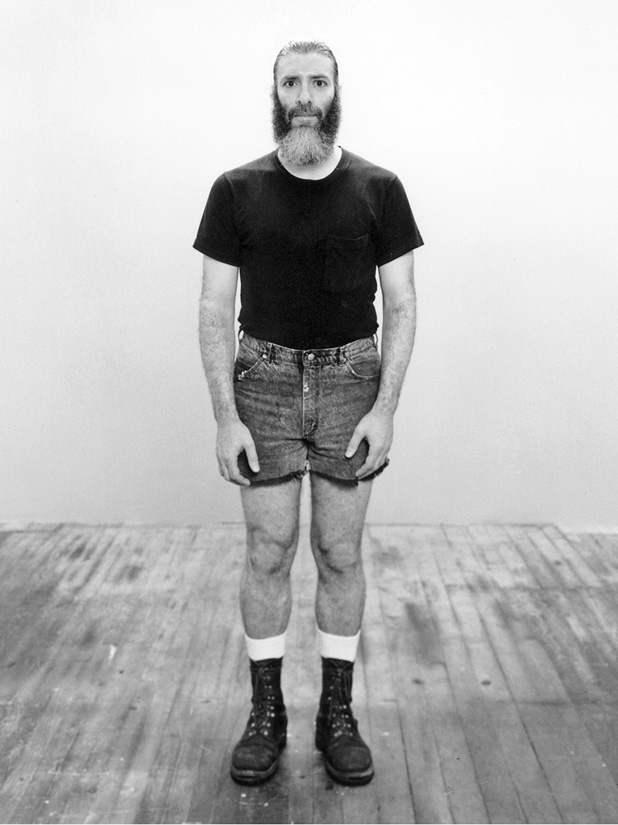

In your series Faggots, you shot gay men in very a very neutral state and environment — exactly the opposite of what most artists might do. It’s like you were trying to reveal the banality of sexuality. Your website mentions “the impossibility of stereotyping.” What were you trying to achieve and why? Did you succeed?

One morning while my partner and I were working in the garden a truck slowly drove by and the driver yelled out “Faggot”. Startled, I called out “Who, me?” and he said “No, the other guy”. This got me thinking about what the signifiers are of “the other” in a neutral, non-specific setting. So I asked men to come to my studio, stand on a spot on the floor and stare at the camera – no gestures, no expression, no body language. I then photographed them and examined the subsequent images for “signs”. I found none.

What is your fascination or non-fascination with Las Vegas? Is it the over the top kitsch? Why do you think so many people go there?

People go to Las Vegas because they like to dip their toe in the illicit and naughty despite the fact that those attributes, in the case of Sin City, are for the most part manufactured illusions. But I don’t go there to photograph those illusions – I go to record the evidence of what happens behind that hallucinatory scrim.

What is your photographic training, and what equipment do you use?

I have no photographic training – for better or worse I am self-taught. In the past I’ve used a Hasselblad and a 4 x 5 view camera. I now use a Nikon DSLR almost exclusively.

You are shooting everything 35mm digitally now? Most photographers usually start at 35mm, and then move onto medium format or 4×5. You actually went the other way and have gone to small format? Is that mostly for ease of use? Was shooting medium-large becoming a hassle? Do you think you will miss the resolving power of large format, or the look of film?

In my recent work I’m searching for the subtlest of nuances and the digital format lends itself to this exploration by allowing me to shoot extensively without changing film every 36 exposures, i.e. I can immerse myself entirely in the shoot and not worry about the mechanics. But primarily I like the rendition of digital files and the control I have over the final output. These days I don’t see much difference between the look of film vs. digital and feel if one format gives me more of an edge in transferring my concepts to paper, then that’s the winner. That said, I’m toying with the idea of going back to the 4 x 5 for a specific project but hope I convince myself otherwise…

Why are you thinking of going back to 4×5, and why do you hope it does not happen?

I don’t necessarily look forward to going back to the 4 x 5 because of the physical demands, but I’m always willing to break my back for an image. I won’t go into the subject matter, but suffice it to say it requires extremely high resolution and the usage of tilt and shift, which I’ve never been able to replicate using smaller formats or post-production tools.

What are your main goals now as an artist? Are you teaching and is that something you would like to pursue?

I am forever pursuing clarity in articulation, streamlining and sharpening the process of concept to actualization as best I can. I haven’t taught photography but have a great respect for those that pursue that formidable task.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024