McNair Evans: The States Project: California

It’s not an easy task to take on the California States Project Editorship. It’s an expansive state that draws visual artists to its light, to the spectacular range of landscapes, and to its educational institutions. It’s a state rich with communities of photographers on both ends of its borders (and in between). Fortunately, McNair Evans was up to the task, focusing his selections on Northern California.

McNair may call California home, but his work reflects deep roots in the South and the narrative gifts of Southern writers. He has an innate sensitivity to his subject matter and makes work that is thoughtful, well-considered, and intelligent, understanding the human condition and connection in a profound way. He brings those same sensibilities to his editorial work, as evidenced in a recent essay in the California Sunday Magazine, and in an article about that same work in the current issue of PDN. We are grateful for his curation, time and efforts, and for being a shining light in our photography community.

McNair Evans is a 2016 Guggenheim Photography Fellow living San Francisco, California. He explores themes of shared experiences and identity by photographing the American cultural landscape amidst forces of modernization. His personal, often autobiographical, subject matter is recognized for its literary character, unconventional narrative form, and metaphoric use of light.

Growing up in a small farming town in North Carolina, McNair Evans worked repairing track on a 32-mile railroad. He discovered photography studying anthropology at Davidson College (BA, 2001).

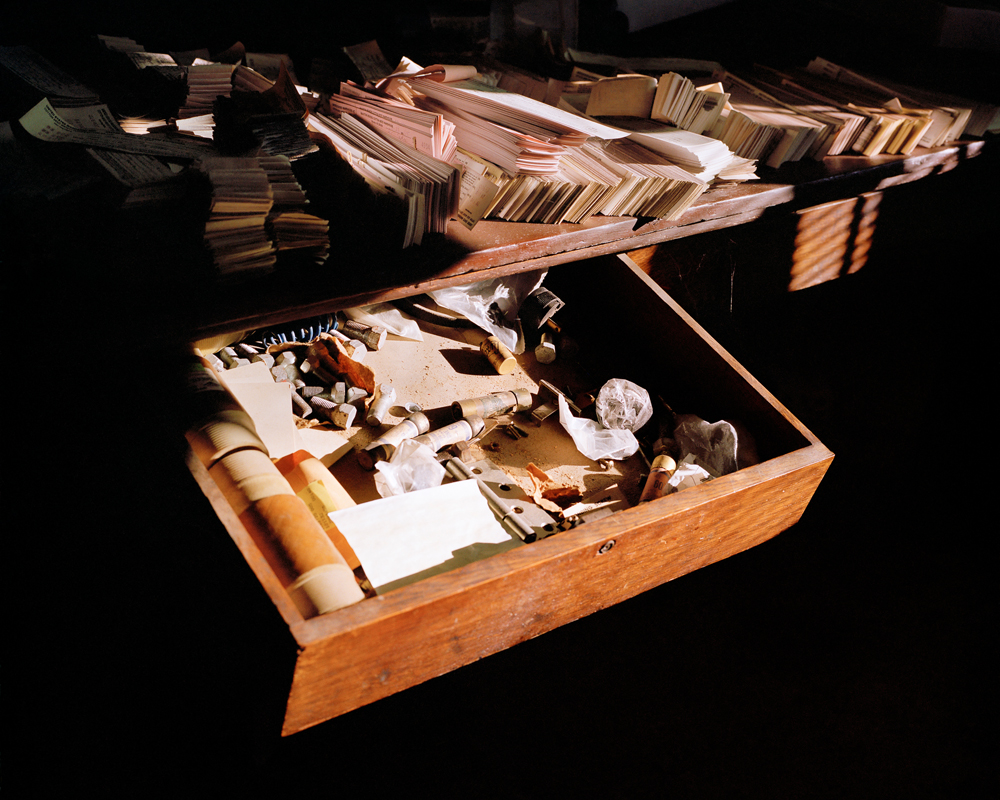

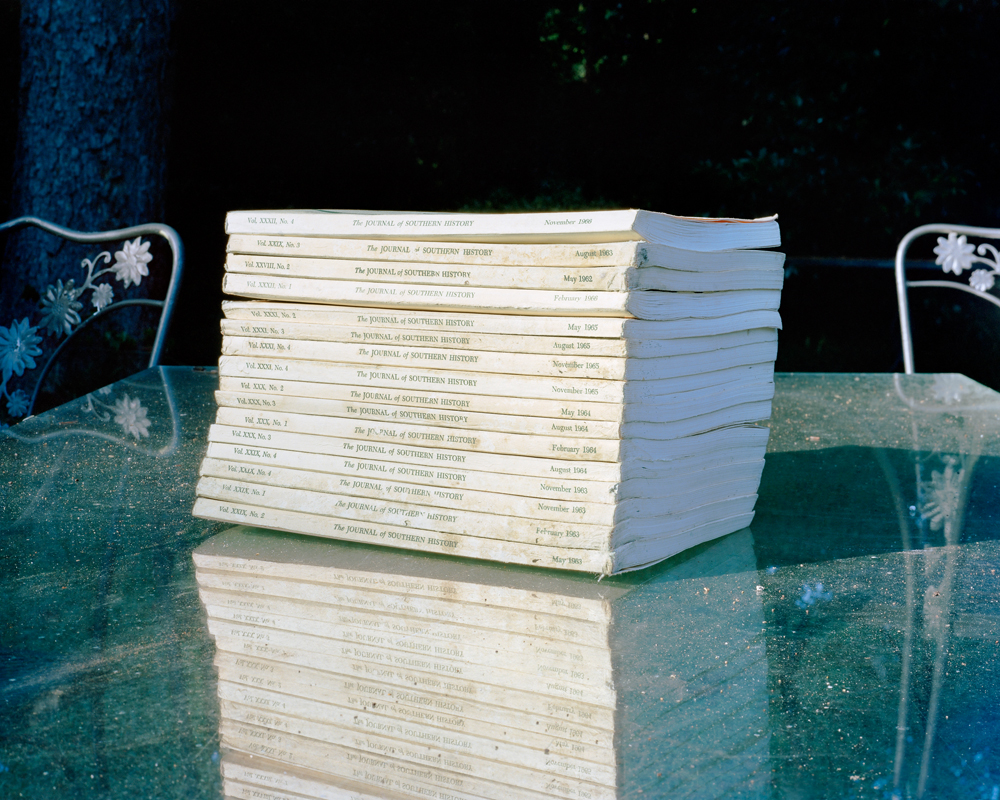

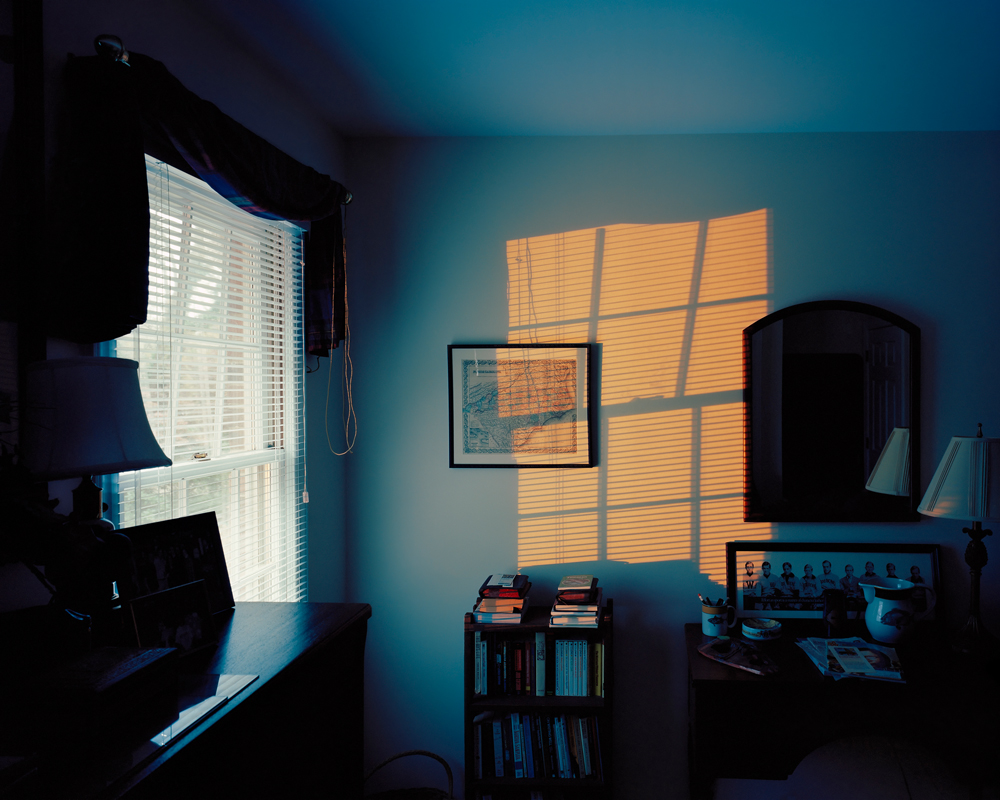

In 2010, McNair Evans returned to his childhood home of Laurinburg, North Carolina to retrace his father’s life and legacy after his death nine years earlier. The themes of this project were universal—the relationship between fathers and sons, the strength of family, and the disappearance of an agrarian way of life. Pre-released at the New York Art Book Fair (Owl & Tiger Books, 2014), Confessions for a Son sold out within months.

In 2014 with a North Carolina Arts Council grant McNair created a public art project compiling Laurinburg’s photographic history through a custom, online platform combining social media ideology with DCMI standards. Content collected will comprise public art installations in downtown spaces opening June 2016.

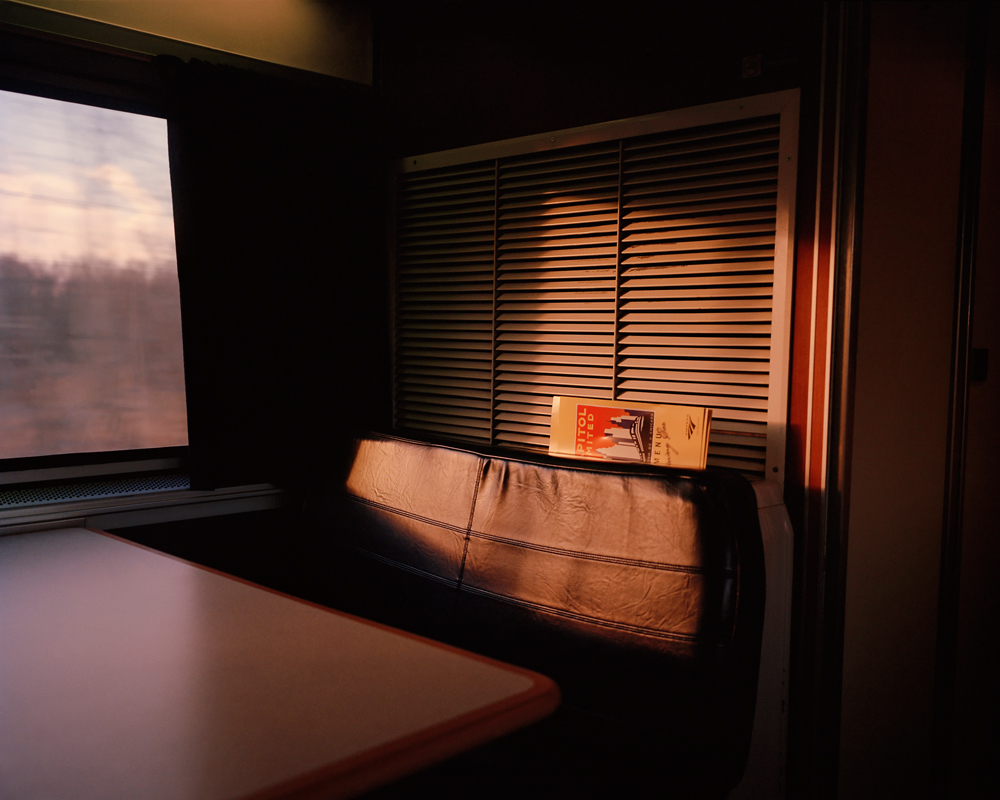

For three years, McNair has taken two-week Amtrak trips to meet and photograph passengers. He elicits first person, passenger-written journals, often about connection and change. Intimate, and at times autobiographical, In Search of Great Men explores a search for hope that so defines national identity.

His photographs are exhibited and held in public and private collections including those of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Sir Elton John. McNair’s work has been featured in editorial publications such as Harper’s Magazine, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The Financial Times, as well as on the cover of William Faulkner’s novel, Flags in the Dust.

McNair is represented by Sasha Wolf Gallery in New York City and lectures regularly at universities and colleges.

California is such a complex and expansive state; is it possible to feel one is a California photographer?

A California photographer yes, but a Californian photographer I am certainly not. Perhaps one or two of the photographers we are featuring this week will shed a little more light on what it means to be a Californian and seriously photographing during this exciting time and place for image making.

There exists in California a very wide, commonly accepted spectrum of what it means to be a photographer. For starters, saying you’re a photographer is about as general as saying you are a doctor. From there I tend to break it down between commercial photography (work for hire created in order to sell or document something), editorial photography (photographs created to illustrate or accompany magazine articles), journalism (newspaper work), documentary (which is kinda mix between editorial style and journalism concern but without the rules of either), and fine art photography. The last of these categories I find to be the most interesting today in California because good art is generally earnest, created out of a true curiosity, interest, or existential need, and innovative, generating fresh perspectives about a subject or photography itself. While there are hundreds, if not thousands, of ways to be a California photographer, the defining zeitgeist of fine art photography is one of earnest innovation.

How did you go about finding photographers for this week?

There are many amazing photography resources in the Bay Area (Rayko Photo Center, Pier 24, SF MOMA, and the Larry Sultan Visiting Artist Program to name a few) that attract serious image makers. In all of these locations I’ve bumped into enough amazing photographers to call it a community, and wow what a community we have. Some of the featured artists and I meet to share ideas and portfolios, while others have mounted impressive shows in local galleries or museums. All of the artist we’re featuring are based in the Bay Area and blur those neat categories I described above in pursuit of their creative curiosities. Each of them is a friend, all of them are teachers, and in every case they inspire me to revisit my own photography with a renewed awareness and sense of urgency.

Does living in California shape your work in any way?

I split my time living and working between San Francisco and my native North Carolina. While I do have a current project rooted in San Francisco, the majority of my work is made in the southeastern United States or the country at large. For the most part San Francisco is an editing, printing, and finishing place for me. This is where I return to read, research, and assemble bodies of work.

The Bay Area (which some consider to be 45 minutes from California), is a constant photographic education. There are amazing schools here, including the California College of the Arts, Stanford, and the San Francisco Art Institute. Between local schools, those resources previously mentioned, and ongoing conversations with many amazing artists that live here, I am forced out of my comfort zone on a daily basis. What are the fundamental concerns of photography, how should it evolve, and which tools are best are constant questions in the Bay Area. This intellectual and creative climate certainly shapes the outcome of my projects.

The Bay Area also provides assignment opportunities with national and international publications. As an artist, this is the closest I come to the current technology bubble, and it’s a wonderful opportunity. Editorial assignments expose me to new people, ideas, and creative problems. They challenge and inspire me. Within today’s editorial market, living in a location where this type of paid work is regularly available offers a tremendous amount of opportunity unknown to many incredible photographers working in other locations around the country.

So much of your work is about light—a quality that I associate with the west, maybe because of the sunsets or the open landscape—did that sensibility develop in California?

In many ways photography is like music and language. It carries regional dialects and characteristics, markers of the creator’s cultural origins. Nationally produced media deconstructs traditional geographic boundaries and homogenizes regional divergence. These days you don’t have to live the The Delta to grow up listening to the blues.

Light, like rhythm and beat within music, is fundamental to photography. How a photographer uses light is an indication of who and how they are. Some people craft this identity consciously and it is always changing. For others it is rooted deeply in their regional culture. Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi is a great example of this. Cool, even, articulate light is something I associate specifically with the northern Midwest. These characteristics are indicative of the geography as well as Midwestern culture. As his trip progressed he brought this distinctly midwestern sensibility with him into the Southeast, and that provided a very fresh perspective.

Perhaps I have not tried to become a Californian or my childhood still dictates who and how I am. My light sensibility is much more indicative of a southern heritage than my time living in California. William Eggleston, William Christenberry, and Sally Mann feel more relevant than photographers I associate with California light, such as Ansel Adams, Larry Sultan, Mitch Dobrowner, and RJ Shaugnessy, to name only a few.

You’ve had a remarkable couple of years, not only as a fine art photographer releasing a sold-out monograph, becoming a Guggenheim Fellow, garnering a prestigious New York gallery, and on top of that, your editorial work has also been stellar. Can you speak to this trajectory and your early years in photography?

It is easy for all of us to see one another’s careers as an immaculate conceptions of accomplishment. Freud theorized that we prefer to see successes in this way because it allows us to overlook all the hard work such recognition requires. Even Ryan McGinley who, more than anyone in photography, would appear to have catapulted from obscurity into the international stardom, talks about his career a long sequence of small baby steps that eventually begin to add up.

My development as photographer has been a slow, and at times really difficult, process since first becoming interested 15 years ago. As a BA anthropology student photography was a means of ethnography, describing the customs of individual peoples and cultures. Though I couldn’t yet articulate why, shared experiences and common languages that transgressed cultural boundaries dominated my pictures.

I was on track to become a fly fishing guide in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem, and my photographs explored this new spatial experience of Rocky Mountain geography. Most of the pictures were subject dependent and terrible. When the opportunity to spend six months photographing in the rural Cuchumatanes Mountains of Guatemala arose, I jumped on it. There I photographed like an anthropologist, identifying people by their social roles with the vision of completing a holistic cultural description.

Back in the United States these pictures facilitated photojournalism opportunities, a 2-year stint working with the US Ski Team’s Official Photographer, and freelance editorial and commercial photography assignments focused on outdoor sports and adventure travel. Working around the world making pictures in gorgeous locations and remote cultures, I was living the dream, but with a major problem. Ultimately the pictures I was taking were utterly meaningless to me.

I moved to San Francisco to learn more about photography on the gut feeling that I had a bigger calling. Tremendous teachers such as Alec Soth, Mike Smith, and Lon Clark shaped my understanding and vision, and I invested everything into a project that felt utterly unavoidable creatively and personally, Confessions for a Son, (Owl & Tiger Books, 2014). The accomplishments you cite from the past 2-3 years have been a growing culmination of 13 years hard work, sacrifice, and blind faith.

When I spend time with your two projects, Confessions for a Son and In Search of Great Men, I am first drawn to your abilities as a storyteller and then to the sensuality of the images. Both projects are imbued with a sense of another time and memory, but not nostalgic in the traditional sense. Do you see connections in the two projects?

Absolutely. The lingering anthropologist in me credits societal expectations instilled through cultural symbolism for modern life’s greatest existential conflicts. Beyond aesthetic similarities both projects deconstruct such symbolism in pursuit of emotional truth and a sense of self.

Confessions for a Son uses personal relationships with my own father and hometown to deconstruct fatherhood, generational expectation, and an often romanticized agrarian way of life. Initially confused and angry, I grew to know my father as a teenager, college student, co-worker, and lifelong friend who lovingly withheld business realities. I realized shortcomings and success and found empathy with a man who faced so much loss. The images offered only thin ephemeral connections to a broader narrative. Story specifics transcended into the universality of love and loss, leaving room for others to insert their own ghosts.

In Search of Great Men follows that trajectory by combining original photography with first-person, passenger-written accounts. The lives and stories of those traveling on passenger rail illuminate tensions between the individual and society’s expectations.

The train can be a beautiful way to travel but, for the most part, long-distance trains are used by people trying to get their lives together, find work, or reunite with people they love and hope will love them back. This project explores that search for something just out of reach and a bit intangible. It is about the desire for change and the possibility of hope fulfilled.

In Search of Great Men uses the symbolism of trains to explore of our nation’s psychological landscape, collective identity, and idealized myths.

When I travel alone, I find I have an inner narration of what I am experiencing, almost as if I am making a movie for myself, noticing the light, the behaviors of my fellow travelers, the details and nuances of what surrounds me. In Search of Great Men feels that way to me: cinematic and elevating the people who crossed your path. I can only imagine that you felt a profound connection to humanity after your many train trips.

Any scenario where people openly share their lives presents the opportunity to look at verses with them. Identifying someone as different than me may be perceived as a really ‘safe’ position, but I agree with Thomas Merton, “Of what avail is it that we can travel to the moon if we cannot cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves?” Listening to other people’s stories and sharing their countless aspirations is an incredibly bonding experience. Each time I photograph with someone, I tend to fall in love with at least some small part of who they are. After fifteen days straight, I’m tremendously inspired but emotionally exhausted.

Can you share a bit of your process of work and what cameras you use?

Projects generally begin with one photo or small idea. I keep notes of these to see what lasts: individual photos, project titles, editorial stories etc. There has to be a tone and pitch that feel true as well as a critical tension. Ideas that continue to hijacking my presence after six months or a year develop into projects. During that time I’ve researched previous work relating to that topic and considered the right process. I use all types of cameras from digital 35mm to 8×10, and believe that a very specific pairing between the tool a project’s concept is essential. This helps me organize my work, and not feel stressed out about trying to work on everything all the time. Confessions for a Son was predominantly shot on a Shen Hao 4×5 field camera, while In Search of Great Men is made exclusively with a Mamiya 7.

The one group of cameras I’ve yet been able to really use are the viewfinder-less digital cameras like iPhones and small point-n-shoots. Thus far I find those arm-distanced screens surrounded by the remainder of the world completely undesirable for anything other than referential notes.

Currently most of my work is about striking about balance between the what and how of an image. If something is too subject dependant, I struggle to make meaningful pictures. When my photos become overly ephemeral, they begin to lose potency. I look for strong design (color, line, contrast, scale, juxtaposition, etc.) and equal balance of narrative (recognition of subject) and metaphor (what else the picture may mean). I need to feel a deep resonance when I see a potential picture. I’ll then work that scenario until I’m confident the picture will communicate what I felt.

Bringing pictures together into a larger project is like composing an album. Each picture has a tone and pitch that should build on it’s predecessor, foreshadow what’s to come, and reference other pictures included in the group. One picture can change the entire sequence.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Meghann Riepenhoff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 14th, 2016

-

Kevin Kunishi: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 13th, 2016

-

Adam Katseff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 12th, 2016

-

Nigel Poor: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 11th, 2016

-

Carlos Chavarria: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 10th, 2016