Emile Askey: Monuments are Forever

Emile Askey has the unusual heritage of being half black and half Greek and a homeland of Australia. I first met Emile when we were classmates in the MFA program at Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of the Arts in New Brunswick, NJ. Over the summer, when I was in Arkansas, he drove across country from New York City, and we went out to photograph in the Arkansas Delta for a day. While on that trip, we talked about Stephen Shore, someone who has been an influence for Emile, and we pondered the question, what does it look like when we go out and make pictures on a cross-country trip, like Stephen Shore or other white male photographers like Robert Frank, William Eggleston, Joel Sternfeld, Lee Friedlander, Soth, etc.? Does race enter into that way we capture the landscape? We are still working on the answer.

Emile shares his experience as a black photographic artist:

For me, it’s complicated. People often comment that I’m “from everywhere.” Born in Los Angeles, raised in Australia. My father is African-American, but mixed like most of us (to some extent) with traces of french speaking creole and Native American. My mother, an Australian Macedonian-Greek. Before moving back to the United States as a 23 year old, I’d considered myself to be a black man. My father was black. I was black. End of story. However, over last 10 years living here my identity has become as muddy as my genealogy. Australian, not born there. African-American, looks white (“could pass for Puerto Rican,” said my sister). Weird accent. “What are you?”

My personal identity completely informs my photographic art practice. I feel this intense desire to make art that is explicitly political, but then I take landscape photographs in the vernacular of so many white men who are canonized in photographic history. I think a lot about this quote from an interview with Mel Edwards “Rarely are African-American artists asked to discuss principals and dynamics and art on a level of aesthetics at the higher level. We’re always asked to explain something about how do you feel about being ostracized or left out but a real aesthetic discussion?” Because of how I look (other), I’ve never been asked about politics of my work by somebody who doesn’t know me personally. Yet, that’s all I ever want to talk about.I guess I think a lot about uncertainty in my work. Sometimes I want a photograph to be a statement and point at something pretty clearly. Other times, and perhaps a lot of the time, I want a photograph to be read the same way my ethnicity is. “What are you!?” I think that more accurately represents the world we live in. There are times when things are clear and straight to the point, and other times to be confused, uncertain, and lost.

Emile is a Macedonian-Australian and African-American dual-citizen and photographer. He is interested in photographing the landscape as a way meditate on one’s personal and family histories, and how current and historical social, economic and environmental issues, alter the way one traverses and sees the world in front of them. Emile was born in Los Angeles and raised in Melbourne, Australia with roots in Austin, Texas, Iberia Parish, and Florina, Greece. He received his MFA from Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University in 2015, and currently teaches photography at Rutgers, Parsons The New School for Design and Columbia University.

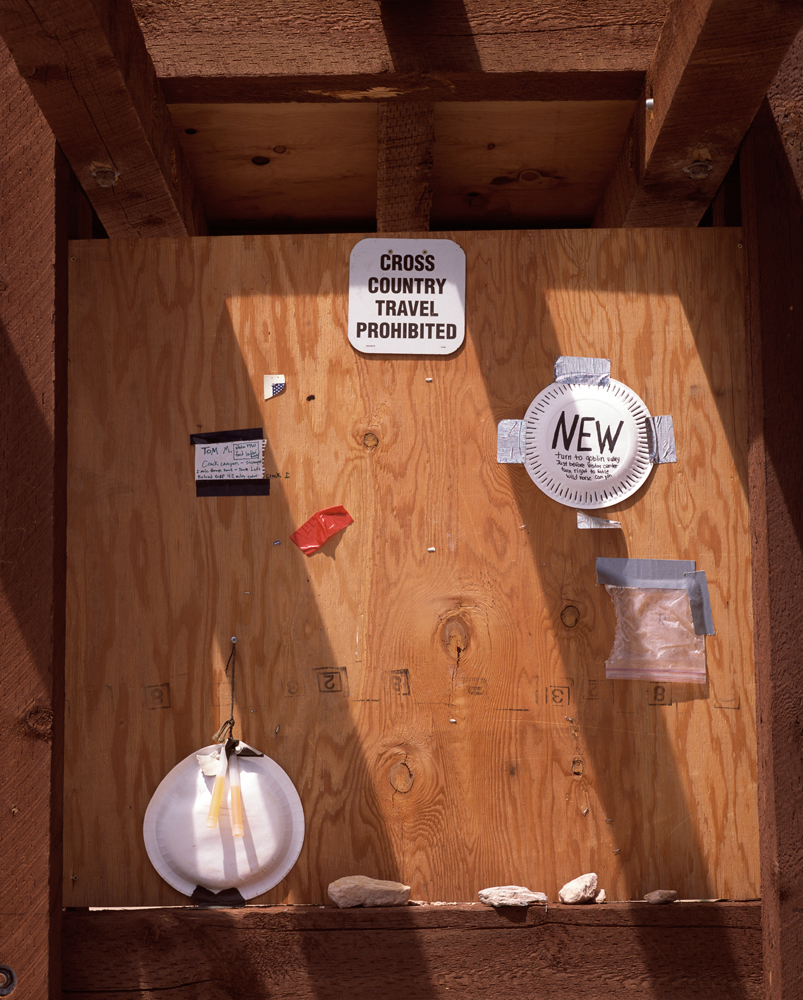

Monuments Are Forever

As a photographer, it’s not hard to be enamored with the American landscape. One can think about the country coming into it’s own with the development of the camera. Wars, industrial and cultural revolutions, social rebellion, and civil rights, all have their iconic images through which we can feel connected to our collective history and perhaps imagine our personal histories that we were unable to experience first hand.

Then again, that puts a heavy burden on the photographer, and the historian to present an unbiased and “truthful” account of the events they are documenting. Or, maybe that’s just what we expect. That our information is unbiased, uninfluenced and impartial, presented for us to be consumed as fact. Were the first photographs of the American West taken to show the physical, and unsullied natural beauty, or were the photographers commissioned by the railroad barons to bring the masses west and make them a fortune in the process.

There are always alternate histories. A William Henry Jackson photograph of the Yosemite Valley taken in the 19th century presents this landscape as some idyllic, Eden like, untouched Utopia, a place to create a national park and preserve for future generations. Of course, the Yohhe’meti that had inhabited and held the Awani sacred for thousands of years were excluded from these photographs. So was the systematic genocide being committed on them by settlers and the government. And what about the California Gold Rush that existed right outside of the future parks boundaries and have had long lasting Superfund like toxic effects on the ecosystem.

I feel implicated in all of this. As a child, I traveled with my family as somewhat of a casual observer. We would hit up all of the important American Monuments between family visits. Anything between Los Angeles and Austin was worth visiting. Yosemite? Check. Grand Canyon? Check. Zion? Check. Carlsbad Caverns? Check. Occasionally we’d get lost. Roswell, New Mexico? Check. Or sometimes we’d have a family reunion or an old relative who wanted to say hello and we’d end up in New Orleans, Atlanta, D.C or Monterrey Bay.

The strange part for me is that I don’t particularly remember anything about these Monuments, just peripheral details that have stuck with me. I remember feeding deer at the Grand Canyon a Hershey Bar, listening to George Michael’s “Careless Whisper” in Mum’s VW Beetle, picking up hitchhikers, trying to guess ‘Tucky Chicken while playing “I Spy,” or being so afraid of a thunderstorm that I refused to go to the bathroom for 14 hours.

And this is where I and myself. I initially began this project as an investigation into tourism of National Parks. I started out by tracing a line across the country to loosely follow the footsteps of earlier trips. Part of this was my own desire to be outdoors and to experience the Monuments as an adult and the other part was to document my own experience in these places in the same way my family had.

My first observation was how foreign all of these place felt. I couldn’t place my- self with any of my own memories. There might be ashes here and there, and of course “Wow” moments where I’d succumb to the intensity of what I was seeing. The second part was seeing how quickly others seemed to navigate these spaces. There would be the family in the mini-van holding up traffic for 20 miles or so, that would pull up to the scenic lookout, pose for a picture, and hop back in the van. Then there would be a couple doing the same thing, or a tour bus full of Europeans recalling the footsteps of their colonial predecessors. People seemed more concerned with the photograph they were taking on their iPhone, than their own direct experience. Everything was being mediated through an LCD screen of some description. I pointed my own camera at them, while taking the same pictures of myself with my iPhone. I had to update Instagram too.

As this body of work of has evolved, my sole focus on tourists started to feel limiting. I didn’t enjoy the restriction of my travels to one particular idea. It felt dishonest. Dishonest to the landscape and its complex histories, and to my own experience as well. I thought back to those first photographs of the Yosemite Valley. I thought about how we consume information without a trace of nuance or subtlety, and a heavy dose of bias and skepticism. Even though our world contains endless detail to engage and explore, to often we put things in terms of black and white, right or wrong. “10 Things You Won’t Believe”. If it’s not entertaining, ignore it all together.

My photographs are quiet. I am merely a 6’7” arrangement of bones, water and atoms, with a dodgy back, wandering my way across a minuscule area of the earth’s surface. But, I let my own history, and that of my ancestors travel with me. I can’t help but be afraid while traveling alone in the Deep South. Just like my father was 60 years ago. Nor can I forget Stephen Shore talk about taking photographs of food because, according to him, the food in America at the time was so bad, while debating whether the carnitas taco that I’m eating in Texarkana is in fact the best taco I’ve ever eaten. And then I get lost while using a GPS, and wonder how people ever used the stars to navigate. I travel with my own bias and rules, but I try to be sensitive to what I don’t know. I create my own Monuments and watch others do the same.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Shari Yantra Marcacci: All My Heart is in EclipseApril 14th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024

-

Broad Strokes III: Joan Haseltine: The Girl Who Escaped and Other StoriesMarch 9th, 2024

-

Brandon Tauszik: Fifteen VaultsMarch 3rd, 2024