Kalen Goodluck: The States Project: North Dakota

©Kalen Goodluck, Sahnish Scouts search for Kristopher “KC” Clarke, a truck driver murdered by his boss, in badlands. North Dakota, from Contrails

I first encountered Kalen Goodluck’s work on the website Natives Photograph which features work from a range of indigenous visual journalists. Goodluck focuses on a variety of subjects in his practice, but two series — Contrails of a Fevered Dream and Fort Berthold — look at specifically at issues and places in the Fort Berthold reservation in northwestern North Dakota. In both collections Goodluck photographs in analog black and white and examines the changing conditions in the reservation as a result of natural resource development. In his Contrails series, for example, Goodluck uses infrared film to interpret the rural landscape as a dynamic entity, and as a witness to a history of nefarious activity on the land. His second series, Fort Berthold, looks at neighborhoods, community spaces and his family’s home in the reservation.

Kalen Goodluck is a documentary photographer, photojournalist, and journalist from Albuquerque, New Mexico. His work has explored indigenous human rights issues on his tribal home in Fort Berthold, ND, food scarcity and justice in the Hudson Valley, cultural identity and landscapes in his home of New Mexico and New York.

Goodluck attends the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism in pursuit of a MA Journalism degree. He writes for NYC News Service and BKLYNR. He received a degree in a B.A. in Human Rights with a concentration in Latin American and Iberian Studies. At Bard, he was an editor, writer and photographer for The Draft, a student-run human rights journal, and a member of the Native American Journalist Association (NAJA).

Kalen comes from the Diné (Navajo), Mandan, Hidatsa, and Tsimshian tribes and is a tribal member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota.

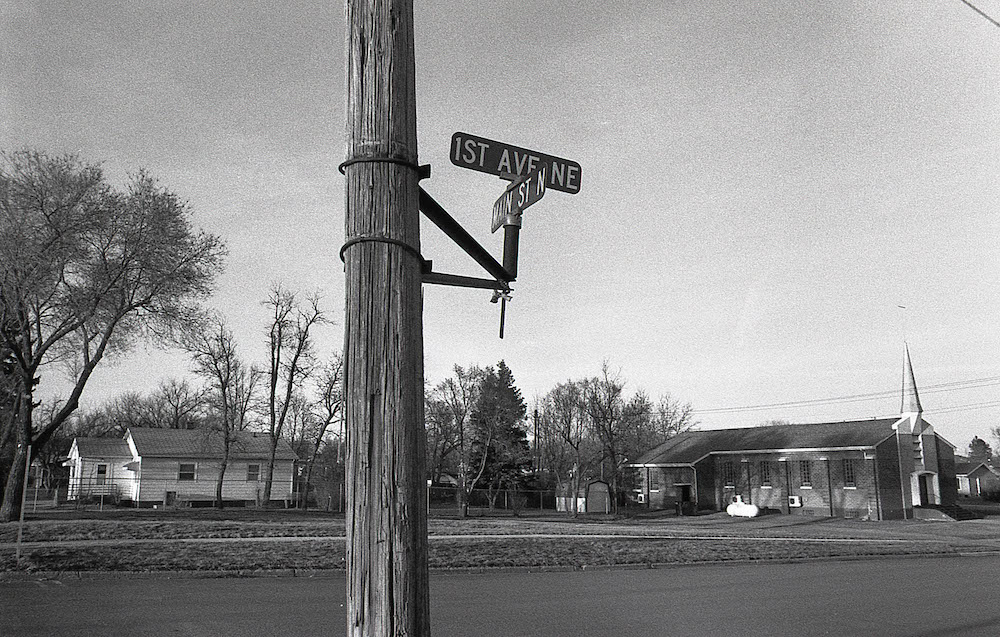

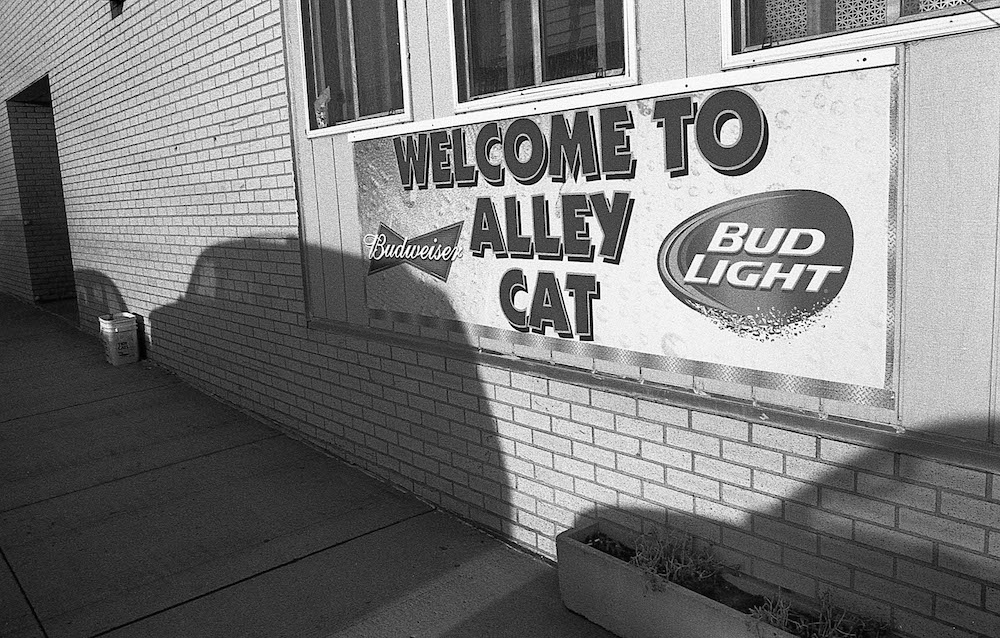

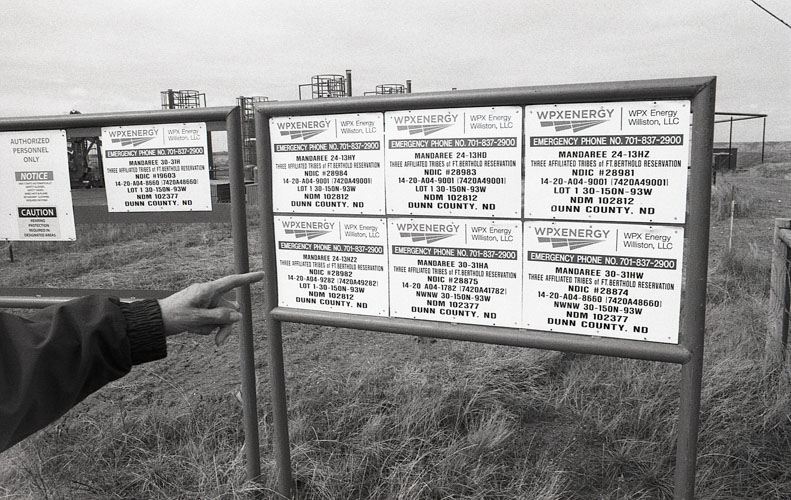

Lissa Yellow Bird-Chase searches for the missing and murdered in North Dakota. An Arikara woman, she is a Three Affiliated tribal member of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. From 2006-2014, an oil boom rocked the small reservation, attracting thousands of transient workers…and crime.

KC Clarke, a trucker for oil company, went missing February 22, 2012. His boss, a hitman and a driver all took part in his death and lonely burial, deep on the badlands.

The homelands of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara turned into a prairie of flares, oil pads and money. Yellow Bird has been searching five years. KC Clarke is still missing.

Our contrails dissipate behind our bodies in clouds of heat and turbid memory. In the delirium of life we find no cure for this fevered dream and no relief from unqualified impromptu awareness, perception. – Kalen Goodluck

You have traveled and worked all over the country. What is the best thing about photographing and working in North Dakota?

My grandmother’s family is from Fort Berthold, so it’s always been a special place to return to. Sometimes it feels like the center of the world.

I grew up hearing her stories about growing up in Elbowoods, a southern town that doesn’t exist anymore. It was destroyed by the flood brought by the construction of the Garrison dam in the 1940s.

I like to connect what she tells me to the land, and then to myself.

Forrest and I usually stay at a house that used to be my great aunt Phyllis’ house, but is now kept by my great aunt Marilyn.

It’s always funny going back. I’m always carrying a camera and wear clothes that look much more urban because I mostly live in New York now. We get stares the moment we walk into a gas station, driving on the road, walking around the neighborhood or sometimes heckled while taking photographs.

Though I love going back, I’m definitely a bit of an outsider.

©Kalen Goodluck, Lissa’s little cousin explores a hilltop near Fort Union Trading Post historical site from Contrails

Can you talk about what motivated you to create this series? How does this project relate to your other work?

I saw Richard Mosse’s Aerochrome infrared photos that he shot in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It brought a new layer of perception to the many ongoing wars and the disturbing aftermath.

I began to look into film stocks that could interpret different frequencies of light and render them visible..What I realized, working with true black and white infrared film is that I was working with much longer exposures than I was used to, which meant I carried a tripod with me wherever I went.

People began to feel like ghosts. A photo capturing human entropy.

What were some of the thoughts and feelings running through you while creating the Fort Berthold series? What have you gained from making this work?

I think I gained a lot of confidence in my intuition as a photographer. I could react to the spontaneity of a situation and compose something that I felt was authentic.

I do wish I spent more time photographing people though. It’s still a challenge for me to shoot more than landscapes.

There are a lot of photographers who create by shoving a camera in someone’s face and blasting them with a flash. It always felt aggressive and unnecessary. It kind of makes me feel ashamed to be a photographer when I see it.

I prefer to feel accepted or unintrusive when I photograph, which is a huge fucking challenge because everyone seems paranoid when there is a photographer in the room.

Native people especially don’t like photographers. And I can see why. They are sensitive to their own dignity and when you take their photograph without permission, it can be triggering.

There are rules and laws that govern photojournalism, but there are also cultural rules that photographers sometimes violate.

©Kalen Goodluck, Loren Yellow Bird, Lissa’s uncle, and his daughter in front of their house from Contrails

How did you get started in photography?

Honestly, it all started with my brother, Forrest.

My brother was actually the one who was getting deep into photography as a teenager. He bought a low-end DSLR, a T3I, and started making short films. He was always someone who pursued his interests at any cause, at whatever means. He’s absolutely a person who lives with no excuses.

I would walk past the bathroom and see him agitating tanks of film, pouring and mixing chemicals—doing god knows what. He would coax me to shoot film so he could teach me to develop it on my own. It took my a while to warm up to the idea. He also tried to show me the movie Children of Men by Alfonso Cuarón and DP’ed by Emanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, who would later be my heroes for storytelling and visual language.

It was when we both went to visit our family in North Dakota to explore an oil boom in 2016 that I started take photography seriously. We shot Portra 400 and delta 100, developing it ourselves in the basement of our great aunt Phyllis’ house.

Later on at college a friend of mine named Stephen Joyce, who is a gifted and sensitive photographer, out of the blue, gave me a Canon A1 film camera, a set of lenses, and a flash.

I had mentioned to him in passing that I had wanted to begin shooting film. Stephen shot an utterly tender and personal photo project about his father. At the time I was mostly interested in photojournalism work, humanizing and documenting the stories of others. It never occured to me to create a work that was aimed so close to the photographer’s soul.

I was mostly self-taught, aside from trading tips with Forrest and other photographer friends. I turned to Youtube, as one does.

What’s next? Anything new you can share?

Right now my time is occupied by reporting for NBC’s Investigative Unit, my own reporting and taking classes at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

So for the moment I’m taking photos for me, because it makes me happy. I develop film in my sink, hang it up to dry in my closet, and then scan the negatives on my desk.

I’m still working on “Contrails of a Fevered Dream.” It was conceived to be a work to document the far-right authoritarianism of this administration and this sense of dystopian future lingering in our collective imagination.

The treatment of immigrants, criminalizing black people, rise of a once closeted-white nationalism and denial of climate change can be too hard to bear at times. But I think we have to look at it.

While I think there is a lot of hope in the story that Lissa Yellow Bird-Chase brings to my work, her searching for KC Clarke in the badlands, there is still an angst that I can’t get over. I think that shows.

What is one book that you think every photographer should read?

Oh gosh, that’s a hard question! I think poetry or listening to music is a good place to start.

I’ve been reading Sylvia Plath’s poetry collection.

When I think about writing, or rather writing about myself, it kind of scares me to distill my thoughts and experience into words on a page. It shows how much I know myself and I realize that I really don’t.

Sylvia Plath knew herself.

What photographers or photography inspires you?

There are so many. I look up to the photographers in the collectives Natives Photograph, like Russel Albert Daniels and Josue Rivas, and Women Photograph photographers like Daniella Zalcman.

The masters: Gordon Parks, of course; Dan Winters; Chivo Lubezski’s work in Children of Men; and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

What else is giving you inspiration these days? Something you are listening to, seeing, or reading?

One of the most creative experiences I’ve had was listening to Kendrick Lamar’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City on repeat in the darkroom. I try to replicate this feeling when I’m photographing.

Sometimes I play movies in the background when I write, too. Movies like Hunger by Steve McQueen, Children of Men, 2001, Zerkalo (The Mirror) by Andrei Tarkovsky. Anything that breeds contemplation.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024