Developer: Rana Young: The Rug’s Topography

I had the wonderful experience of sitting down with Rana Young to discuss the intricacies of publishing her very first monograph The Rug’s Topography. The book is a beautifully intimate look at the delicacy of a shifting relationship, and the space for intimacy that photographs can provide. It was published with Kris Graves Projects, it launched on January 10th, 2018 alongside an exhibition at Filter Photo. With an ever-growing societal conversation growing around gender, this work feels like a timely exploration that does its diligence to explore romantic and platonic relationships through portraits and ambient images. I couldn’t be more thrilled to begin the Developer series with an artist whose work I’ve respected for such a long time. Rana and I met almost three years ago at the National SPE Conference in Orlando and was such an open and friendly person from the get-go. Seeing her work and career develop over the last few years, I know her and her work will continue to grow and be such an important voice in the photo community.

Rana Young is an artist and educator based in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Rana holds an MFA in Studio Art from the University of Nebraska Lincoln where she was an Othmer Fellow and a BFA in Studio Art from Portland State University. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, as well as published online by Hyperallergic, VICE, Huffington Post, British Journal of Photography, and The New York Times, among others. Recently, Rana was selected as a winner of Magenta Foundation’s Flash Forward 2018 and LensCulture’s 2017 Emerging Talent Awards. Rana launched PHOTO–EMPHASIS, an online platform for highlighting contemporary works made by photography educators, students, and practitioners, with Alec Kaus in June 2017. In collaboration with Kris Graves Projects, Rana will release her first monograph, The Rug’s Topography, in January 2019.

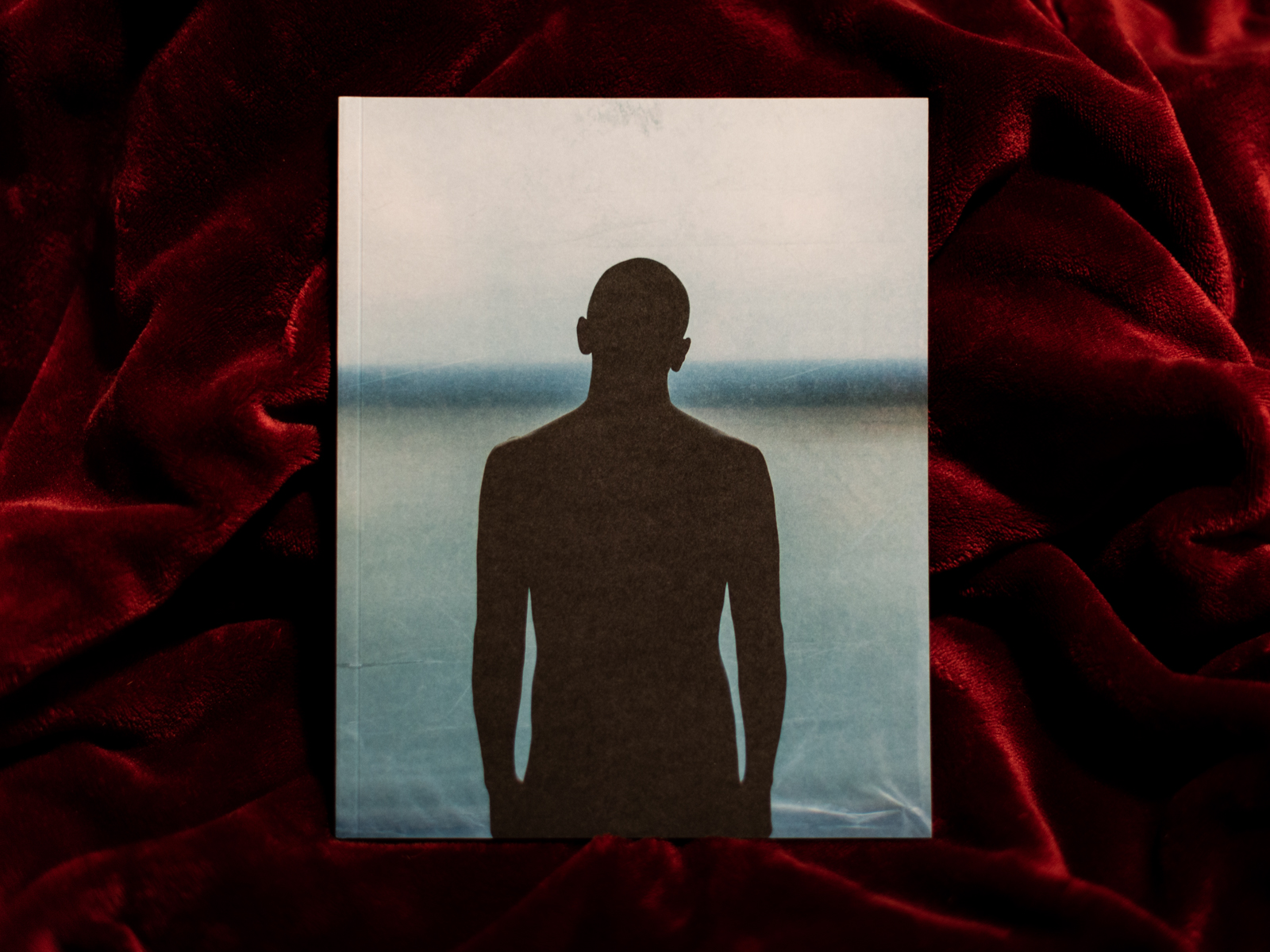

The Rug’s Topography

The Rug’s Topography began with me photographing my intimate partner of six years. Simultaneously, we were facing an internal conflict: how we identified as individuals differed from the roles we occupied in our partnership. As we began to grow apart romantically, our anxieties rose in response to the distance widening between us. Our individual identities within a romantic context stemmed from the commonality of both having witnessed predominantly cisgender roles during our formative years. Our performance of those expectations was perpetuated by inexperience and an impulse to adhere to, or in my case “correct,” our potential family structure. Recognizing a shared inherent foundation opened our dialogue and together we began unpacking our preconceived notions regarding societal norms. Collaborating visually to express our reflections served as a catalyst for the reconciling of our emotional intimacy in the midst of a separation. It is through the juxtaposition of gaze and gesture we create blended self-portraits, expressing our emotions in relation to who we were and who we’ll become.

My photographs employ themes of tension, voyeurism, and transition to represent interpretation of self. I construct images that balance organic intimacy and cinematic theatricality by implementing symbolism, color theory, and seductive lighting. Using a directorial approach and a single subject allows me to create an environment that transforms viewer into voyeur. The singular vantage point and lack of reciprocal gaze invites one to silently observe an unfolding narrative. However, the personal account is never fully described and the viewer must bring their own history, biases, and prejudices to interpret the imagery. Transition within this work is highlighted through the notions of gender and time. Though the viewer is privy to feminine interventions placed upon the male figure, faint physical changes sequentially manifest in the subject. Rigid musculature and posture is overcome by delicate and poetic gestures; the manicuring of body also becomes a form of sublimation. The ambient photographs, which signify fleeting moments, mark points of personal evolution. Emphasis is placed on the threshold between public and private, as well as the implied or literal mirror embodying introspection. Life comprises moments navigating both the literal and psychological space; my intention is to render that dichotomy. – Rana Young

Brennan Booker: Thank you so much for talking with me with today. Let’s start with a little bit of background. Where did The Rug’s Topography begin? Was it immediately clear you were making these images as a larger body of work or more sporadic?

Rana Young: The short answer is no, I didn’t start off even considering it as a body of work. It was in the very early stages of graduate school, and at that time, you’re just trying to figure out what to make work about and why. You hear time and again to “photograph what you know.” I’ve always been more comfortable responding to my immediate environment, rather than “hunting” for those moments.

Although I consider myself socially extroverted, I spend a lot of my free time alone or with one or two close friends. At that time, that was mainly with my partner, Matty. It was a very strange time for us, however. We had just moved to Lincoln, Nebraska and Matty had just started a new career there, and I was just starting graduate school. There was a lot of uncertainty about our futures, both independently and as partners. Matty wasn’t really shy in front of my lens because they’d been a subject before in my work, but always typically as a stand-in for what I was conceptualizing. At the time, it wasn’t directly about Matty.

We began with me making work to highlight intimacy and privacy, tension in our home, and in our relationship. I wanted to articulate that uncertainty or that tension I was feeling. I explained my feelings to Matty the best that I could. Matty was feeling similarly and agreed to participate in my photographs. When we started to make more images our conversations expanded to be more about our relationship and about our individuality within the relationship, and we started to think about the future… it snowballed from there. In the beginning stages Matty was identifying as male, and when we started to have these conversations about our individual identities within the relationship, Matty unveiled to me that they wanted to identify as gender-fluid. Since then, Matty has transitioned to fully identifying as female. With that being said, it’s a little complicated how I talk about it because I’m attempting to describe three different contexts. In the beginning, I more or less aimed to highlight this transitional period, and then it quickly deepened into how Matty and I were feeling in a more intimate way. The images began to echo our personal narratives, despite that not being the original intention.

It took me a long time to think of it as a body of work. It was a one-step at a time process, and to be really honest, it was the first body of work I’d ever made photographically. So, even that aspect of making was very new to me. I was used to the process of making a collection of images about a particular time or situation, but it was more like working in volumes. I wasn’t used to contextualizing the work on this level and that’s what drove me to go to apply to MFA programs — I was anxious for the opportunity to work that way for the first time.

Finding the balance between your voice and aesthetic as an artist and the vulnerabilities of someone else can be difficult. How has the changing of this work as a personal project into a monograph changed how you navigate those vulnerabilities? How has Matty’s reaction been to the making of the work and now its form as a monograph?

RY: Creating a book has given the work an ultimate sense of permanency. It becomes a visual archive from my perspective, as well as Matty’s. It archives a very specific chapter in our lives and even though the images themselves are staged, they’re based on a personal narrative that stems from our lives and our truths within those lives. Even though we were creating these heightened constructions of our perceived environments and situations, it became a visual record of that time. It really solidified that permanency through the process of choosing images. Matty has always been very open and almost passive about the work being public. I really value the trust they put in me in terms of judging what types of venues I submit to and things like that. But, it’s important to keep in mind that the meaning of the work can get away from you. Once you put it out there you have no control over who interprets it and how people “read” it. There’s always been that looming idea; what if someone doesn’t understand the project, or what if they come to a different conclusion? However, we know what it’s about and why we made it. Now we have a permanent record of these versions of ourselves. We consider the work to be a sort of blended self-portrait.

In terms of turning the work into a book, I tried to treat that process as delicately as making the actual imagery. I wanted to be as thoughtful as possible about how a viewer would navigate through the imagery in a linear way, while also showing it comprehensively. I definitely consider the book to be a final edit.

I love that answer. I do want to step back and talk about what you said about relinquishing control over who sees and interprets the work that we make. Do you have any lessons learned or advice you might give to somebody that’s struggling with that same experience?

RY: Yeah, I think it’s really important, especially within a structure like academia to absorb as much feedback as possible. But, always remember that you’re making your work and not someone else’s. You have to determine how to utilize feedback and implement it into your work. Or, perhaps, choose not to. I made this work during the hardest time in my life. Graduate school is very challenging in that way. It really forces you to decide what you’re going to protect about your work/self and what you want to open up about to the viewer. I had mentors that encouraged me to put it all out there. Not in a pressured way, but to put it out there and not be ashamed of what kind of conversation it might start. I also had mentors that wanted me to be protective of our personal narratives; I had to find that balance. I do place some burden on the viewer to investigate why I made this work and tried putting enough context out there to make it clear. Conversely, I do save some deeper context for private situations like this interview, or an artist talk, too.

How has the way you consider/think of the work changed as you transitioned from work made in an academic setting to monograph? What considerations did you have to make that you weren’t conscious of before?

RY: Since I was making the work in graduate school, there were “checkpoints” with our scheduled critiques. You had to be prepared to share work during pre-scheduled “deadlines.” Making the book was really special for me because I got to do that completely independent of anyone else. I had a lot of freedom in terms of sequencing and working with Kris Graves was a really wonderful experience. He’s such an advocate for artists and truly believes in you if you believe in your work. He encouraged me to design the book the way that I wanted to given our budget and timeframe. He’d look at it, make (crazy awesome) suggestions, and I could choose to implement them or not. The mutual trust was extremely comforting and made for a relaxed process.

Initially, the project was primarily portrait based. Seeing portrait after portrait of the same subject became a visual redundancy that I really struggled with. It was easy to feel like you’re making the same image over and over again. I wanted to create these visual breaks and decided to add ambient images. They become metaphors for feelings and I believe ultimately really helped the book edit when viewing work linearly. I wanted to navigate between past and present and even project the future. The ambient images help create a sense of pause that allows an entryway to another point in time.

Were there any standout lessons you learned when sequencing on your own and worked on the images independently? I remember when I left school to take time off I had many moments where I realized what I learned in school wasn’t the total truth about my art making.

RY: I definitely learned how much I value community, feedback, and having the opportunity for people to look at my work. Making the book was the first major thing I’ve done without the voices of my peers and mentors in a school setting. You have to trust the network you have and hope they don’t mind you sending them edits. It’s important to remember that nobody has to give you their feedback and that it can even become burdensome with so much happening in everyone’s lives. I think the lesson for me was to value those willing to look at what you’re making and invest in that. After academia, you’re very quickly alone and unless you’re privileged enough to pay-out a lot of money for review events, there isn’t anyone to give you objective feedback without that investment in your community. I definitely had to learn to be more patient with myself and the process of working alone. I recognize that I’m not the only one who will hold this book, so reaching out to others for feedback was really important. Obviously, I’m the closest person to this work, but as a book, it becomes very removed from me and something that people experience without my direction. It’s important to consider all of the possibilities of how your work can be interpreted and be okay with that.

For a lot of artists, a monograph feels like an ending to something. A closing chapter, if you will. How does a monograph change the finality of this work for you? Is it finished or will you continue this body of work?

RY: It’s a bit of a relief, now that it’s done. I made careful decisions with the book in terms of the images selected and I feel good about the final edit. There are also a few secrets in the book that don’t typically represent my work. For example, the work isn’t presented chronologically because I don’t think about it in a chronological way. However, there are definitely little nods to the passage of time. The rose image that opens the book was one of the very first ambient images I made and quickly became a signifier for the potential of this conversation and this body of work. Soon after that image, there’s a close-up portrait where Matty has my eyeshadow on and signified the close of our romantic relationship and the beginning of our platonic one. The last portrait in the book is the last one I made for the series. These markers remind me of when things were made and who Matty and I were at the start and end of this project.

Has this experience of publishing your first monograph changed the way you’re approaching the work you’re making now?

RY: I’m working on a new project now feel like I’m coming at it in a sort of backward way (from what I’m used to). When making The Rug’s Topography, I wasn’t sure where it was going in the beginning and I was working from “start to finish” in terms of conceptualizing and then making images for the project and trying to fill in those gaps of what I wanted the images to represent. In the beginning, I didn’t have a solidified conceptual underpinning until, to be honest, the end. I was appreciative of that because I could look back at everything we made and then choose the imagery that I felt was the strongest and reflected what I was trying to visually articulate.

With this new work, I’m thinking about that context ahead of time while working with a photographic archive and responding to it through my contemporary images. I’m also not making on what feels like, a schedule now. Like I said earlier, graduate school has all of these “checkpoints” which is a really unique structure that I don’t have anymore. It’s really at my discretion what goals I want to set for myself, so these days I’m in my head a lot. I’m considering the outcome in terms of context or conversation before I put the images together.

All work making has points where we start and stop. Even some where we may think we’re actually done with it. What advice would you give to a newer artist to get through that?

RY: I would say to stop looking at what you’ve already made and just keep making. I have a bad habit of assuming that I’ve already made what I want to convey. As I continue to photograph, I find that the final iteration has yet to be made. So often I make an image and say, that’s the “final thing” and I really want to break out of that. I suppose my advice would be not to assume you’ve already made the image you want to make. If you’re feeling stagnant, there’s always an opportunity to re-work an idea which could potentially evolve into something entirely new for the better.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026