The Intention to be Unintentional: A Conversation with Daniel Arnold

Daniel Arnold takes photos that defy definition. While his practice of walking the streets for endless hours and shooting candid moments would place him squarely in the “street photography” camp, somehow he doesn’t fit in. There’s an eccentricity which overlays his pictures’ earnestness, resulting in a halting power that threatens to be poetic but just as often veers into absurdity. Or maybe that’s just how I read them. If you read the many things that have been written about Daniel, you will see a lot of accusations that he’s somehow either a fake, or overly aggressive, or “random” in his aim. None of these things are true. Arnold is the rare kind of photographer who no one knows how to be: he has amassed a large audience who are not necessarily photography fans, per se. His work’s reach has extended beyond the ghetto of the “Photo World.”

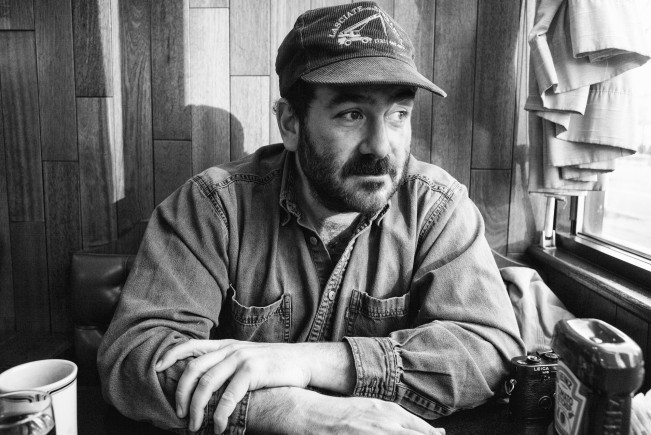

Often described as an Instagram phenomenon, Daniel Arnold burst into his odd condition of having real-world recognition back in 2014 when he made an unprecedented $15,000 dollars in a single day on Instagram in response to his offer of 4×6 prints for $100 each to help him make his rent. The unexpected windfall also resulted in a lot of mainstream press. Soon he was invited to shoot for websites, newspapers, magazines, brands, and more, but the cornerstone of his life and practice continues to be long hours of solo NYC street wandering, and very few exhibitions. His 2019 solo show at the gallery Larrie in NYC, and accompanying book, were curated from work made that summer, in a feverish mode, partially stoked by a discovery of a kindred spirit in poet Walt Whitman. For this conversation I met up with Daniel at the classic Waverly Diner in Greenwich Village on February 17th, 2020, a couple weeks before his 40th birthday.

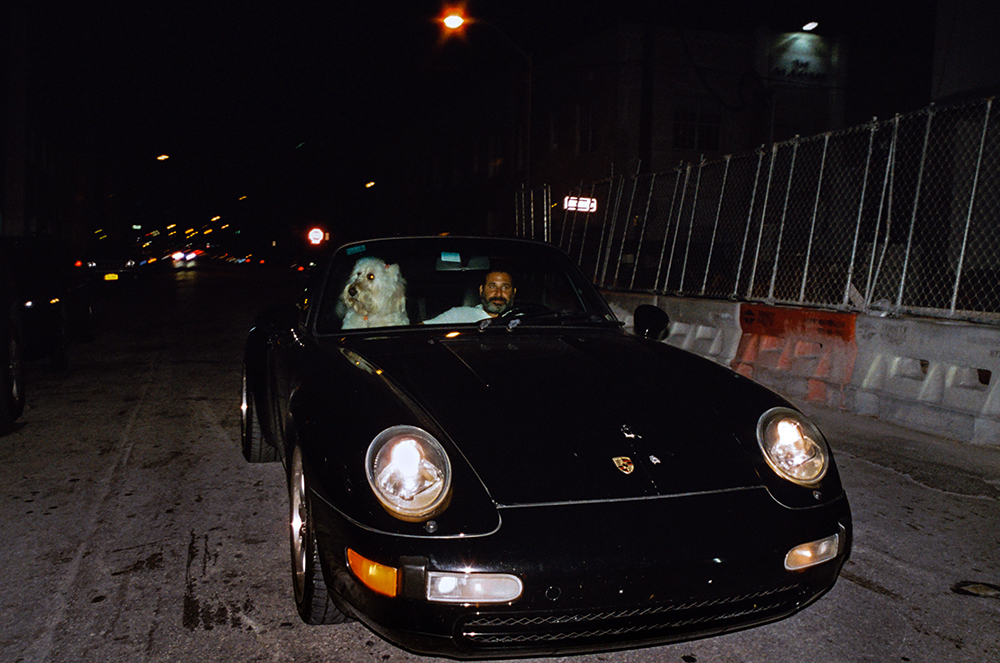

Daniel Arnold is a curious, marathon-walking weirdo, a self-employed spy and obviously a photographer. His habit evolved un-ambitiously, in the background of a 10-year writing career, where it wasn’t subject to much outside influence. What began as a practical memory-aid, and a reason to brave intimidating new rooms, eventually capsized that decently stable writer life in 2013, when Arnold quit his job to open all of his time up for wandering. Since then, he has curiously indulged in the odd opportunities a photo career affords, shooting everything from dog parties and haircuts to the Met Gala and the Republican National Convention. But no matter how many vegan shoe look-books he shoots at all-night drum and bass festivals in the mountains of rural Japan, Arnold’s practice stays pathologically rooted in compulsive investigation of his own city’s odd, exciting streets.

Reuben Radding: I was at that Vogue Q&A with you at the Roxy Hotel where the moderator asked you whether you “grapple with the ethics” of taking photos of people without their permission, and you simply said, “no.” And he seemed kind of shocked. Like he was expecting another kind of answer and wasn’t sure how to follow that up. And I remember you rescued him by saying something along the lines of, “I think all of this, everything, is for everybody.” Did that point of view take some time to arrive at? I know that was always my instinctive belief, but when the question is framed that way it feels difficult all over again.

DA: There’s a million arguments to be had about ethics, especially in this era of everything being a crime, and I get stumped by that question, but I’m always happy to try to talk my way through it. It’s a surprisingly helpful privilege being interviewed, in that I don’t necessarily have answers to their questions, so I end up learning as much from having to talk through them as anybody learns about me from reading my responses. To be held accountable that way has I think really helped me kind of clarify the borders of my own thinking and experience.

RR: I had to do a long exploration of the ethics of my practice in grad school, and I dreaded doing it, but in the end I wound up being grateful for that process, because I came to understand that my own ethics come from my deeply held personal values based on my experience. And one of the values I identified was: I place a high value on a sense of risk, which is all over this street photography practice, and it can manifest in any number of ways. Do you relate to that?

DA: I think it connects really heavily with what we’re already saying about the question of ethics. Because that question kind of gets in the way of the answer. There’s a totally false implication that there’s some code of ethics out there, some concrete thing, some black and white thing. And I do think––I mean in so many ways beyond ethics, but definitely as it relates to ethics–– that part of this endless task, part of this experiment with the city and with yourself, I think, is learning what your ethics are. I mean, there are things that I would have done five years ago that I would never do now. Nothing extreme. It’s like the tiniest nuances. Probably an onlooker wouldn’t even notice the difference, but in an internal way the photo practice ends up being a vehicle for learning what your ethics are, and rather than sitting in judgment from a distance and thinking “what is right and what is wrong?” I think it’s a much more responsible engagement with that problem, if you’re mindful about it, to go every day and put yourself in the way of the public and repeatedly take the ethical tests that arise and figure it out as you go, every day.

RR: Yeah it’s very safe to sit back and decide ahead of actual experience what you think is right and think others should live by that too.

DA: I’ve always felt like that was one of the great, great gifts of New York, is that… you know, they say we’re in a bubble blah blah blah. I don’t think that’s right. It’s that there is no bubble, no cushion, and you’re so piled up under and on top of every other kind of person that you are very in touch, especially if you’re walking around actively looking at it every day, like scouring it for details every day, you know the experience of being a person so much better, in a way that makes it impossible to be blindly prejudiced. If you’re prejudiced, there’s a firsthand experience that made you that way. It’s not pre––it’s judice! I also think it does you the great service over and over and over again of jamming down your throat that you’re not special, and that’s just kind of a very unifying experience. At least my version of it, to go and really look whenever I have time…I feel like any ethical sense of the world that I have is so enriched by that practice. I understand people want it to be controversial. But it’s the opposite! It’s so of the supposed victim. It’s bothering to know what people are instead of…even if there’s an angle where you can say it is objectifying or you know, exploitative, but not in the way that they want to frame it, it’s a way of learning about being a person.

RR: That’s the way I’ve experienced it too.

DA: Yeah! It’s made me so much better at being in the world. Like it makes me feel a bit psychic sometimes, because you spend so much time thinking about what people do and what they’re thinking and how they feel, and what will come next.

RR: But then back to the framing of questions, like earlier I was recalling the whole question of “do people get mad at you for taking their picture?” which we get asked a lot. And the thing that I try to point out to people now instead of just trying to directly answer that question is say, “maybe what you really want to ask is, “what’s the spectrum of reaction that you get when you do get a reaction?” Cause, you and I both know, often there is no reaction or even awareness. And sometimes the reaction could be something you’d never imagine. Sometimes friendliness. Sometimes curiosity. Sometimes indifference. People asking that question go right to the worst case scenario in their own mind, of somebody getting violent. So, that’s something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about: the framing of those questions, and what it says.

DA: Yeah. Well, and when that question is framed non-critically, as I find it more often is, it really does seem to be curiosity about managing the fear of confrontation. A lot of times I hear street pictures being dismissed as “snapshots,” like if anyone can do it, what’s so special about it? Of course there’s more to it than just bothering to face the possibility of confrontation, but fear does seem to be like the big X-factor for anybody who doesn’t do it. I guess so much boils down to people dismissing what they don’t relate to or understand, at least in terms of, like, fear, and the myth of the threat of photography.

RR: The control factor is really interesting to me, because with things like Instagram being so dominant the assumption has become if you’re taking any picture it is very quickly going to be seen worldwide, which didn’t used to be an expectation.

DA: Instagram is…it’s crazy how deeply it has wedged itself into every one of these conversations. Even if you completely ignore it. Even if it’s not part of your thing at all. It’s just become the language. I was thinking about it today, about how a lot of my time lately has been consumed by weird curveball assignment shit, like fashion editorial. Like, I did a skincare campaign! Who the fuck wants me for a skincare campaign? And I’ve been waking up to the arbitrariness of this choice that I’ve mindlessly made to be a “hired” photographer––like I’ll just try to figure out what the fuck you want me to do, which I guess is just like, capitalism? Or, like which photographers I knew when I was transitioning out of the last version of my life. Commercial guys. But, I was just realizing how much that is, in a way, a function of Instagram. That I stumbled into this weird new unproven source of whatever the fuck Instagram gives you. I don’t know. What’s it called? Clout? Or just some leverage in a new pursuit.

RR: And at just the right time.

DA: Yeah! Right. I totally, accidentally threaded a needle. Without ever quite processing it. I had the option to lean into it hard and be an “influencer.” You know, something’s gotta pay the bills. But then I also had this instinct even in the beginning to rebel against it, like prove that there was some substance, and then it became this gateway into a whole new use of my brain and my time. But in that way, even at its most Instagramlessness, my trajectory is, in a way, a function of Instagram. Rejecting my Instagram story pushed me into this endless cycle of proving to myself that my flukey fuckin’ phone app moment wasn’t a flukey phone app moment! It’s a weird time to talk about photography, cause there’s so many versions of it, it seems like the versions need different names. My way has benefitted greatly from Instagram, but it’s not Instagram photography. I feel that way about digital. I’m not against it whatsoever. I think it’s great. I wish I was better at it. But, I just feel like it should have a different name than “digital photography.” There should be a different word. Gorflag. It’s such a different experience. Obviously the results are similar, but…all these different avenues for turning time into an object, they really could use some new names. Or even better, no names.

RR: I’m always trying to wave people off of the whole question of digital vs analog because I feel like it’s a distraction from the stuff that really matters about a picture…

DA: Totally.

RR: …and from having your own endeavor. It’s like the whole color vs black & white question. There’s no objectivity to this!

DA: Right, well, and it’s also about as deep and significant as “boxers or briefs?” It has no bearing. It’s like, you know, how do you walk? I mean, I don’t exactly know how to articulate what I’m thinking, but it’s so personal. I guess everything’s like that though. I mean when you’re deeply personally committed and hooked on a thing, in a way that makes the world quiet, the meaningfulness of your experience is inevitably lost in translation. Cause it doesn’t matter! You’re just deep in your thing. Like the tool doesn’t even really register, as long as it works.

RR: When I applied to graduate school I wrote this big impassioned essay complaining that the photography world was stuck in old questions, like film vs digital, black & white vs color, fine art vs documentary, etc…and I said, what we need to do is put all that shit away and find the new questions. And they let me in the program, but then 2 years later I was writing my thesis and I realized I never really came up with those “new” questions. I mean, in a some ways I did, for myself, but not in the more broad or empirical way I thought I would, and so that’s one of the things that I’m also trying to do at this point is go, okay, well since I didn’t really do that in grad school I need to do that now. It’s so annoying to hear how my brain still returns to the same questions that I tell people are a waste of time.

DA: Yeah.

©Daniel Arnold, New York, NY – 8/9/18 – Strollers don’t work on sand, but one Long Beach lady finds other ways to move her sleeping baby.

RR: So, what questions seem to matter for you?

DA: Well for one thing, I think that those automatic questions can still be worth asking because you get lost on your way to the answer and then figure out what question is worth asking on your way. But I do agree that old questions, and just any context, the story of photography, success as a photographer, blah blah blah, the model of what doing this “right” looks like, it’s all such poison. I think that applies across all creative fields. We’re so steeped in this stupid rock stardom story. But you have no control. There’s no qualitative…anything! There’s no measure of whether a thing is good or not and so we just grasp at old stories of what it looks like to succeed. Some people get all precious about craft, or I don’t know, how to navigate business, or the art world, anything for a taste of control or an illusion of progress. So the question that stays interesting to me is: what can I do to suppress that instinct and try to have a genuine experience? How can a narrowing classification be an enricher and enlarger of my life? And I think that’s a thing you have to constantly have in your mind because the lack of order, the lack of control, always pushes me backwards. Like, “what am I doing wrong that I’m not in a gallery?” or, you know, “why don’t I have a book yet? Why doesn’t Gucci call?” Any of that shit that, ultimately, is only useful for other people’s lazy consumption of your story. As if you can see yourself more clearly if other people see you in a certain way. I don’t know! I’m lost in the thought of it, but it does feel like one of the only things worth really asking every day, like how not to be in the trap of the story of being a photographer in New York. Cause it instantly ruins it.

RR: Yeah! I spent decades living primarily as a musician, and I see all of the issues that I experienced in the music world replicated in photography all the time. And seeing those same questions in two mediums makes me recognize them all the more. Like I have two views into the same foolishness, which I walk into all the time. And so one of the ones that I really laugh at, that I find the easiest to step outside of as comfortably as anything, is the whole “is it, or isn’t it Street Photography?” Right? Because I went through 20-plus years of arguments about “is it Jazz or not?”

DA: Uh huh!

RR: …and I remember in the 90’s having friends who were much smarter than me, saying “you know what? Let them have Jazz. We’ll still be downtown doing whatever it is we do, and it’s fine.” And the whole Street Photography argument to me is like that, it’s like, well while you’re over there worrying about what the parameters of “street” is or isn’t, I’m going to be doing what I do, and hopefully––like the worst poison isn’t the conversation, it’s the mindset that tells you need to be a certain thing, and so what I hope is that, while I may not know what the “new questions” are, if I could do anything, I’d just find a way to be more free.

DA: Yeah.

RR: And that’s the hardest thing. Cause even having a conscious thought like, “I don’t care whether it’s street,” I will still catch myself thinking, “if I say it’s street will people care more? [laughs]

DA: Right! [laughs]

RR: And then thinking the opposite, like “if I say it’s street will that just lump me in with everyone else who does it and make me vanish into the crowd?”

DA: I don’t know. It’s such a curse to me, to name a thing.

RR: Did you ever make a conscious effort to avoid that terminology for yourself? It isn’t something I’ve seen you emphasize. I’ve seen some people will refer to you as a street photographer, but not always.

DA: Yeah, well, cause the purist street people hate me.

RR: Why?

DA: I don’t know. The only reason to hate on somebody who’s deep in doing their own thing (assuming it’s harmless) is because you don’t like what’s happening in your own life. And honestly, more power to them. Let me be their whipping boy. That’s fine. I don’t even experience it firsthand, I just hear about it. Friends who use messageboards tell me, “oh they’re after you again. They’re talking shit, and you’re just ‘snapshots’ and blah blah blah.” But I do a decent job of really not caring about that stuff. And as far as classifying myself goes… I’m lucky to often get paid for what I’d be doing anyway, and it makes the practice self-sustaining. So I just get to work all the time, whether I have a job or not. And that’s a blinding privilege, because I’m sure I’d feel much differently in the absence of that freedom. But from here I don’t worry about naming anything. I mean, the question worth asking, if we’re still thinking in questions is “how much time do I have left?” And, “how can I use that time to make as much work as possible?” If that’s the question, criticism and praise are basically the same thing. They mean equally little. To enjoy praise, or sweat criticism, or try to name anything… It all gets in the way of working.

©Daniel Arnold

RR: Henry Wessel said that as soon as you name something you’re not really seeing it anymore, which I interpret as, as soon as you name anything your mind is closed. Like now, whether you know it or not you have parameters around something you think really exist. You know?

DA: Yeah. You understand without looking at it.

RR: Like as soon as you say “street photograph” we think we know what that is, even if we think that’s very broad. We still think we know what that is. That shit really bothers me.

DA: It makes it very hard to work. It makes it very hard to have vision.

RR: By the way, I was fascinated hearing about your discovery of Walt Whitman and the epiphany you seemed to get from the connection between his work and yours.

DA: Yeah, big lightbulb!

RR: Did you feel like you were looking for something like that when you stumbled into it? A way to process what you do?

DA: Not exactly. I guess that’s always there, passively. I wouldn’t call it looking for a thing. It’s just a receptiveness to parallels. Something I’ve been thrown by sporadically is, for example Diane Arbus did that manifesto thing that her friend reads on YouTube, or just like any documented thought processes of people who have gotten deeply into this, and having come at it not as like a fetishist of photography, to come upon them now that I’m into my own thing, and read them––and find my own thoughts spoken by somebody else, fifty years ago––that kind of thing always…I mean I have goosebumps thinking about it. And it’s not you know, some mind-blowing thing. It makes sense, but, Walt Whitman was a huge one of those, I guess maybe because, a) the time difference, but also it being cross discipline … it’s nice to think that there is a thing––if you make yourself available to it––there is a thing about this city that is still the same as it was––whenever that was, 150 years ago? This experiment of a city has a certain effect if you let it happen to you, and to find that in Walt Whitman, to find it in such a remote, unexpected place, and so resoundingly, screamed, it’s the same thing. Yeah, that was very exciting to me.

And any time you can feel like…I mean, all the stuff we were saying leading up to this, you know all these sort of grabby attempts at distinguishing yourself from 20,000,000 people doing the same thing as you, and to find a thing, a thrilling, positive thing that makes everyone the same, in the midst of that automatic mindset? I don’t know, you don’t have to be looking. It’s just a thrill to find that. To feel like, oh, I’m not distinguishing myself, I’m tapping into something that has always been here. And to combine that with all the other mindfuckery of just growing up, and all the different things that living in a city with millions of people exposes you to, those universal things just always trip me out. When I quit being a writer, I was working for some friends who had this new-agey art business, and they hired me to do their social media when I was figuring out how I was going to quit my job blah blah blah for a little extra money to pad my fall, and as a gift to celebrate my departure from the previous life, they sent me to an ashram for two weeks. It was the first and last time I ever did yoga. Did it like three times a day, ate delicious vegetarian food, hung out with a guru, I had crazy conversations…I had a really interesting time! The impact of which was never to cross a threshold into a new spiritual practice, although, what I found out most significantly was that all that shit––meditation, yoga, etc––was the same thing I was doing, that there’s just a lot of different paths to this place in everyone’s brain that’s sort of transcendent.

RR: Being present, and connecting to the oneness of all?

DA: Yeah. Be present. Have a purpose. Self-sacrifice. You know, whatever the list may be. Ritual.

RR: Suspending the ego at least.

DA: Yeah! And so that’s just like one of these many times, like the Walt Whitman time, where you find these larger resonances and it’s just reassuring, cause I think that you really need some sort of independent source of confidence that this thing is worth doing, cause it is––it’s crazy, it’s a little embarrassing, especially the way things have gone, like that there’s such an economy of street photography and you know, I couldn’t walk a block today without stopping and chatting with someone––which is great! I love that. It’s so nice to be in a community like that, but really, I think you need some kernel of personal meaning if you’re going to be able to swim through this situation. Cause it is, it’s very distracting. It’s very hard to have a community of photographers in your life and not make that a source of comparison and self-analysis.

RR: What about competition? Do you feel any?

DA: No. I feel pretty immune to it. I mean, there are times where things get under my skin, but it’s not ever about like, someone got a great photo. When someone gets a great photo I feel excited for them! It feels like we’re all working on the same project. It’s a breakthrough for everyone.

RR: So what is it then?

DA: Ehhh, I don’t know, it’s cheap shit. Like, nothing real. It ends up being like, recognition…it’s just the tricks of the business. Like someone gets a certain job or someone gets a certain accolade, or you know someone’s getting recognition where I feel like I’m not. And ultimately I don’t fucking care.

RR: Well, especially if you’re working.

DA: Right. And that ends up being the antidote to everything. And not even just getting paid to work. Which is––that’s just kind of the fix for everything. Hopefully it lasts. I don’t know. I’ve been preaching this the whole time, and if it runs out I’m going to be very embarrassed, but it really does––it makes me feel pretty bulletproof. Not much fucks with me, because I have this thing, like, if the world ended tomorrow I feel good about how I was using my time, and I don’t feel competitive about it. I mean also, again, I’m so spoiled. Like, it’s a cheap world of lists and my name’s been written in big letters enough times that I do get spoiled with an unspoken thing that means a lot more to other people than it does to me, but I don’t know how much it steers my answer, because…you know it’s like the invisible white privilege kind of thing: I don’t know what the world is without the structure of what it is. That won’t translate well to writing, but I think you know what I mean. Like, I can’t fully see anything. I’m not worried about if anybody’s doing it better than me because it doesn’t matter. I would be happy if someone’s doing it better than me. I love to see great work.

RR: Right, it’s like, I don’t mind that people who lived 20 years before me did great work that I don’t know that I’ve exceeded…

DA: Yeah, yeah!

RR: …why would I care whether someone tomorrow is doing it?

DA: Totally.

RR: I was thinking again, sometimes the feelings I have are not in agreement with my actual philosophy and I’ll feel competition with people––competition’s the wrong word––usually more it’s jealousy of an opportunity they got or attention they got, my perceived rewards that they’re getting, but the truth is that success for you is success for photography, and that bodes well for me. It’s not a zero sum game.

DA: Well, and one of the best parts of this arbitrary success part of it, is that I get to go into supposedly coveted rooms and be conscious of that and an agent of it, and get to be like, “you should be looking at this person’s work, you should be looking at that person’s work. This is an exciting job, but you’d be better off hiring this person than me.” And in that way I get to occupy this little puppetmaster secret role of infiltrating the big room, and trying to bring everybody along with me.

RR: They must know that while you might be the one that they know, or the one that they trust, or the one they believe has a track record that justifies making you the call they make, but they have to know there are others, or that there will be more. Of course none of us know what’s going to happen, to our planet, let alone industries, so everything’s fucking temporary.

DA: Yeah. The idea that any of this is going to last is very hard to hold onto.

RR: Do you ever worry about what you would do if what you’re doing became impossible somehow?

DA: I think about it all the time. And it’s always felt like something that could very quickly disappear. I mean I have no illusions about any kind of long-term significance. And that’s another thing…It just goes back to that same thing of like, the question is, “how much time do I have left?” So the priority is NOT like…

RR: Squandering it?

DA: Yeah. Not getting bogged down in all the potential disastrous fates awaiting me. Just like, you’ve got your time, they’re letting you do it, you have all the space to work, so fuckin’ work! And I’m turning 40 in a couple weeks. I don’t know how long I’m going to have energy to go this hard

©Daniel Arnold, New York, NY – 8/23/18 – Miss Coney Island hopeful, Pearls Daily, attracts an audience even under the boardwalk.

RR: You know, another thing you said that I found refreshingly honest was someone asking you about “how did you get over the fear” of photographing strangers, and you said “I haven’t.”

DA: [laughs] Yeah!

RR: I was so grateful to hear you say that. I don’t think people mean to be dishonest, but again it’s the framing of the question. “How did you conquer your fear?” is already assuming that the answer to the problem of fear is to somehow remove it, and maybe that isn’t even it.

DA: Yeah, come on, nothing gets figured out. Nothing gets easier. You just get used to shit being hard. You just get better at letting go. It’s not like you get more to hold on to, you just care less. Like, the things that matter stick a little bit better, and you have a better sense of it, and you just care less. You’re still scared. You still don’t know what the fuck’s going on, but you just get used to being scared. Like you just know that it’s always going to be that way, and then there’s like some relief there. It’s not going to get easier. You just get used to it.

RR: Yeah, how many times did I not take the picture and then feel scared that I wouldn’t have another opportunity like that? Like, which fear am I going to choose today?

DA: Yeah, totally. Well, and then that fear ends up being so helpful. I just got back from Tucson, where the whole city becomes a gem show. And so I was wandering around there and feeling timid in a space where a flash on a camera is like an act of violence, and I was scared to do my thing. But I’ve been scared often enough to say to myself, you know what? You’re here for a day. You’re going to feel bummed if you shoot less than you absolutely can. Like, I remember this fear, and I have all these other times to measure up against, and it ends up being helpful. I remember being afraid. I remember that I got through it. Don’t let it fuck you up like it fucked you up last time. And that ends up being built into the walk-around thing too, I mean, I’m maybe leapfrogging a little bit too much, but to be in the business of failing all day, like all those failures end up sticking in your head and then you see kind of an echo of your last failure, and you’re a little bit better at not failing.

RR: Yeah, that old “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

DA: Yeah! Is that a thing? That’s great! That’s exactly what it is: fail better.

RR: It was…

WOMAN AT NEXT TABLE: Beckett.

RR: Thank you!

DA: [laughs] Sorry.

WOMAN AT NEXT TABLE: No, it’s a great talk, it’s great!

RR: But what if instead of framing the question as being about conquering your fear, make it, “when have you given in to fear?”

DA: Enjoy your fear!

RR: So when have you given in to your fear?

DA: Constantly. I mean it’s every day. I don’t know, I think if you’re in a position to figure that out you’re doing something right. That’s always been a compass for me. I was a fearful kid and my mom was the type––like I was freaked out by bugs, so she would find a bug and just squish it in my face, and like made me watch all the Nightmare On Elm Street movies, and just drowned me in all the things I was scared of which, again, the temptation to mythologize yourself is always there, and I don’t want to do that too much, but it is kind of my instinct to…like if something’s scary? Better get closer! And not cause I’m some brave guy. I’m not! I’m not a cavalier, storming the castle and getting in people’s faces guy. I’m managing reluctance and politeness and fear all day long, and so fear wins at least half the time. But fear is so helpful in that way because you get used to it. If you’re scared all the time it’s easier to be brave. Just put yourself in a position where you’re scared and you get used to it. So yeah, it’s always happening. I mean…has it happened today? Was there any time––well, I haven’t really been able to get in a groove today because I kept running into people, but definitely at this gem show. And just like the nature of how I use a camera, like I shoot down by my waist and look away, almost always. I have to really force myself to compose a thing and be accountable for looking through a camera when I’m taking a picture. So much of it is snuck. Yeah I think that’s the answer that nobody wants to hear cause it’s not particularly fun or approachable, but if you do it all the time it’s just an endless process of like every day you get used to the fear in the morning and by the afternoon you’re a little bit more brave.

©Daniel Arnold, New York, NY – 8/7/18 – A woman talks on the phone and claws at the Rockaway Beach sand as a giant lizard crawls up her body.

RR: So, I don’t even know why I want to ask this question but it just kept coming into my mind when I was thinking about talking to you. What would be the best thing that could happen to you right now, regarding photography?

DA: Mmmm, it’d be nice to be invisible. [laughs] That would help. How’s that for attainable goals? Invisibility would be the best possible development. I don’t know, I’m in a pretty sweet spot right now. I mean it’s a good sign that I’m not wringing my hands sitting around thinking what might make this better. I’ve got a good spot. People think of me for interesting jobs, like ”Here’s a thing that made me think of you. Go figure it out.” And it makes life a) unmanageably intimidating––i.e. I don’t have time or interest to feel pride about any of it, or bask in anything. I don’t experience it that way. I experience it like––I mean I’ve said it a million times, forgive me, but I do I always think of Quantum Leap. I feel like I’m dropped on a new planet once or twice a week. So, it would be great if that kept happening. It’s interesting, like I never know it when it’s happening. I don’t know if awareness would be better or worse. Probably worse. Yeah…it’s nice to be asked that question because I would not have known that the answer is if things could stay how they are for a long time that’d be pretty good. Like in the past week––what have I done? I did a skincare campaign, I’ve told you, the gem show in Tucson, a run-around fancy fashion editorial thing, and I’m going to Milan tomorrow for a Prada show…it’s just like all curveballs, nothing I would choose for myself, and really, truly, I think it’s hard to express this, and maybe annoying to continue to try, but like not in a way that comes with any glory. It’s even better than glory, it’s like a new life-threatening situation every 3 or 4 days. Which keeps me feeling really kind of “to the hilt,” to borrow from the bullfighting model. So do you have an answer for that?

RR: I think what I wish for the most is the freedom of mind that we were referring to earlier, like if I could really have that all the time instead of just knowing that that’s what I believe in and having it some of the time. Like I would really love to have that all the time.

DA: Yeah that would be good.

RR: To where there’s not even a struggle, where it’s just like…

DA: Nirvana.

RR: Yeah, like “why would I even wrestle with those dumb questions?” I think that’s the thing I long for the most, like if the genie would wave their magic hand and give me what I want, I think I would want that even more than invisibility right now. I really do. That would be the best.

DA: Yeah.

RR: Like, if I could really have a free mind, then all these other things that feel like big concerns, whether it’s money, or career, or whether I’m great––that’s all taken care of by that one wish.

DA: And those obstructions…I mean, what would freedom be without the opposite?

RR: Sometimes I allow myself to worry about that, like, if I really had that freedom of mind would I be happy? Maybe part of the happiness that I do get to have comes from having to struggle through not being free. I don’t know. I’d like to find out!

DA: Yeah! [laughs] Right. Look back on your life of worries and think, eh, that was an interesting time! I’ve been having this conversation a lot lately, just swearing up and down that the only value that I have gotten from any of these so-called superficial successes, is getting my hands on the thing that people want and really finding out for myself like, oh this is fucking worthless! [laughs] Looking for the thing is much better than having the thing.

RR: Totally, but I’m sure there are people who would respond that it’s easy for you to say cause you have the thing. Photographers who would be like, “at least you’re working, and I’m trying to make rent!” Do you experience resentment from other photographers?

DA: Good question. [laughs] Uh…not directly, but I feel it. I assume it. If anything, that ends up being my tangible experience of so-called success, is that I feel like I have to apologize, and not because anybody asked me to, but I feel guilty. Why should it be me getting all this attention? And not that I feel like it’s some great gift of the world that you have to be worthy of, but you know, it’s the opposite, I have found in all of my experience with it, it’s a cheap, quick pleasure and then it’s gone, and you need to find a new thing. But yeah, I think that that ends up being my weird demented experience of it, is that it makes me feel guilty. It makes me feel like I have to explain to anybody else who’s doing the same thing why it shouldn’t be me. It’s a very automatic complex and I don’t, so far, really know how to turn it off. Not that I think it’s particularly damaging or anything, and it doesn’t really complicate my articulation of my experience I don’t think, but I just kind of assume that everyone must be like “who the fuck is this guy?! Why is this guy getting all this work?”

RR: But there’s probably people who just flat out admire you for it.

DA: Yeah, but the two kind of mean the same thing, or at least they have the same impact. Like, both are kind of abstract and external and they don’t really make any difference inside. Look, I’m very happy to work, and by work I don’t mean doing jobs, although that helps. It helps to have that constant discombobulator and re-configurer of things, but I just want to work. And so the rest of that stuff kind of comes and goes and doesn’t hit that hard.

RR: You know, the assumption with most art-making is you have an intention, and you try to realize it, sometimes there’s a mistake that’s better than your aspiration, but it’s either realized or it’s not. But in my case much of my work is very apart from what I may have thought my intention was. I have a hard time with so much of the critical language of photography from say the 70’s and 80’s, where there’s such a fetish placed on the act of seeing. I think seeing is an extremely small part of what we’re doing. So often what makes or breaks a picture of mine isn’t whether it looks like what I saw, but more often something completely else, which only the camera saw. I mean, especially if you’re taking photos like you do so often, from chest level and not looking through a viewfinder…

DA: Which comes all the way back to the fear thing, for me. I mean, that is the function of fear, and I’d be worthless without it, because it’s the get out of jail free card for intentionality. If you’re afraid, you can’t be intentional. And that’s what I love about the career side of it is that I’m still scared of my job. Like, very scared of my job. And that’s what makes me good at my job. Cause like I don’t go in and execute a plan, I go in and I’m scared to death and get to the end of it and look back and go, okay what did I do when my brain was in that place where it couldn’t think. And so I end up stacking up proof of what my brain does without anybody at the wheel. It’s so much better than anything I do on purpose. It’s so much more interesting to me than anything I could do on purpose. And you’re right: seeing is none of it. I don’t see it. I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing! I don’t see the picture. I feel a thing. I know that there’s like, energy here, and things are lined up in a certain way, and that I need to point it that way and push the button, but like, I don’t look at it and get it right. If I’m trying anything, if I have any intention, it’s not to be intentional.

RR: That’s not taught very much.

DA: And I couldn’t have been taught it anyway, because if I had that in my head then I’d be seeking it. This is a thing that I only know looking back. This is a thing that I’ve noticed as I survive. Like, “oh, this is interesting because I could not have done it on purpose. This is like my animal brain.” Once I got that in my head I was like, “okay, keep going. Don’t ask any questions. Stack up proof of what your brain does on its own.” That stays interesting to me.

RR: What else stays interesting?

DA: [gestures out the window] The city. It’s funny, like, there’s definitely an ebb and flow to it where…I mean how many times can I walk down the same goddamn street? But, so far the answer––so far there is no answer! So far it stays interesting.

Reuben Radding is a photographer, writer, and musician based in New York City. His award-winning street and personal documentary photographs depict elusive or unlikely candid moments, and intentionally provoke unanswerable questions in the viewer’s mind. Radding’s work has been exhibited in galleries around the world, and in publications like The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Hamburger Eyes, Time Out, Hyperallergic, Downbeat and others. His work has also been featured at the Miami Street Photography Festival, The Center for Fine Art Photography, and the Focus on the Story Festival. His first book of photographs, Apparitions, was published in 2013. Radding has been an instructor with the New York Institute of Photography since 2013, and has taught workshops or lectured at New York University, The School of Creative and Performing Arts, Marble Hill Camera Club, and others. Since 2017 he has offered a series of street photography workshops from his Brooklyn studio. He earned an MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts from Goddard College in 2019.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anna Guseva: The Black Night Calls My NameJanuary 26th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Student Prize 2025: Top 25 to WatchJuly 20th, 2025