Granville Carroll: Storytellers

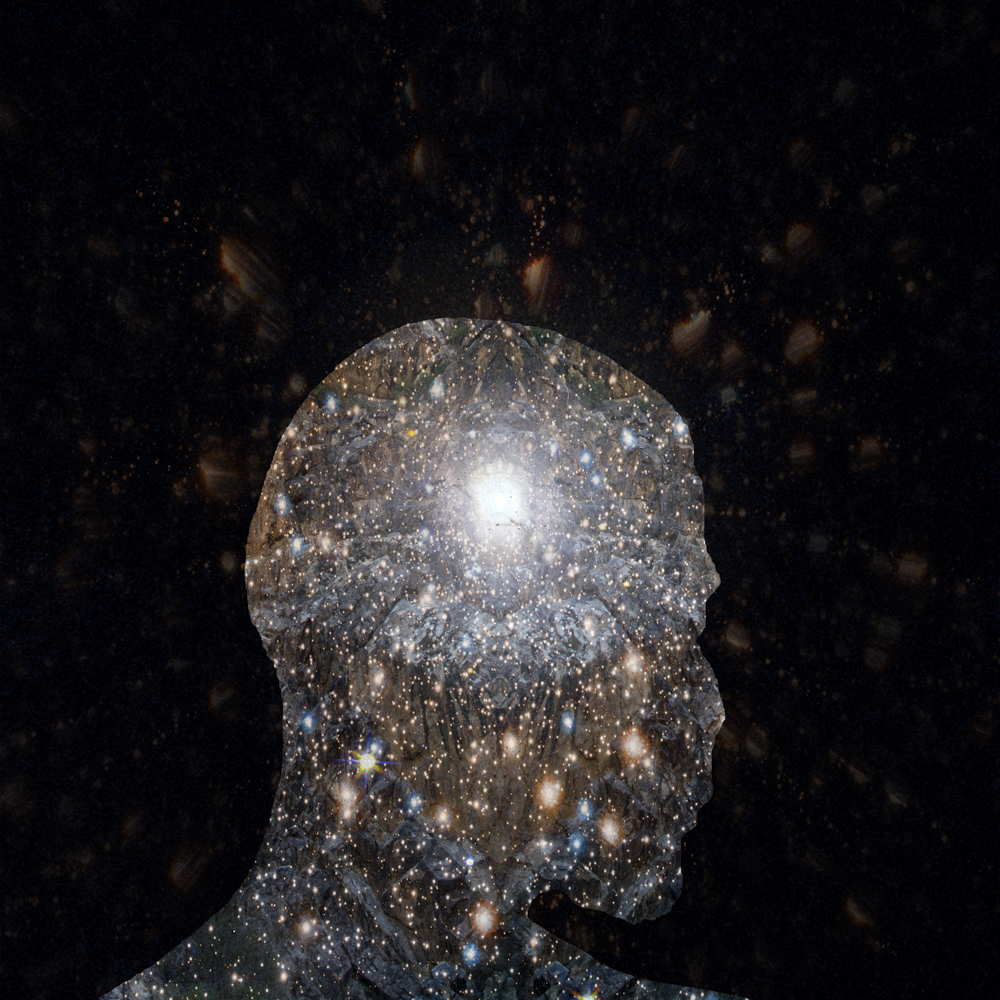

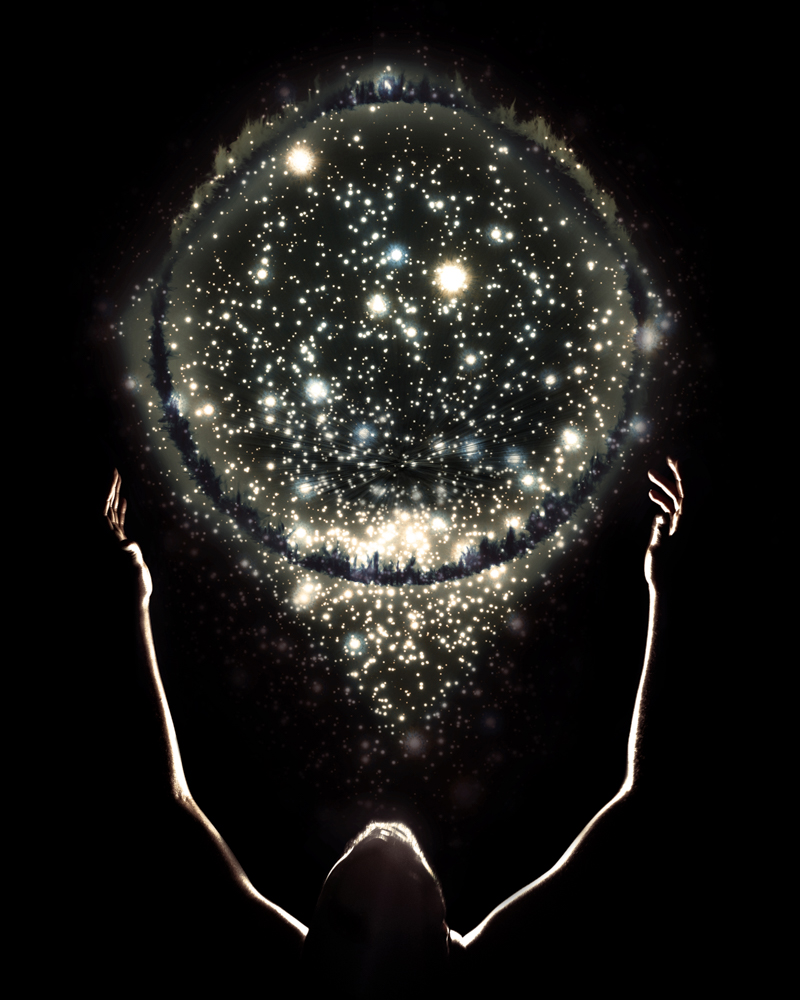

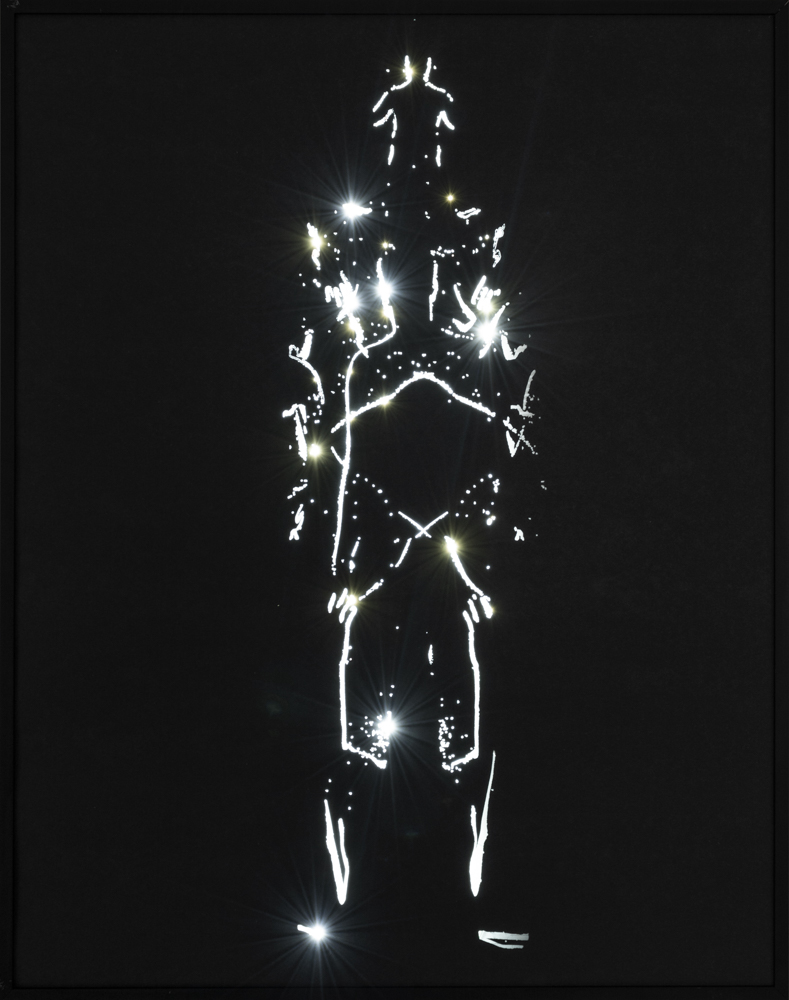

The average adult human is approximately 60% water. The idea that we are fluid beings both physically and spiritually is undeniable and yet historical context, the stories that shape our worldviews, and oppression both past and present, often remove this from the reality we consciously experience. Through a process that Rochester, NY based artist Granville Carroll (@granville_carroll) describes as a reimagining of identity through Afrofuturism, landscapes are deconstructed and digitally rebuilt, portraits are reduced to silhouettes and filled with starlight. In some ways this process is reminiscent of the life cycle that binds all beings: growth, decay, and then new growth. However, perhaps more accurately, it dismantles the familiar and with its pieces creates cosmic scenes of healing that suggest not only a future for black life but one of prosperity, connection, and wholeness.

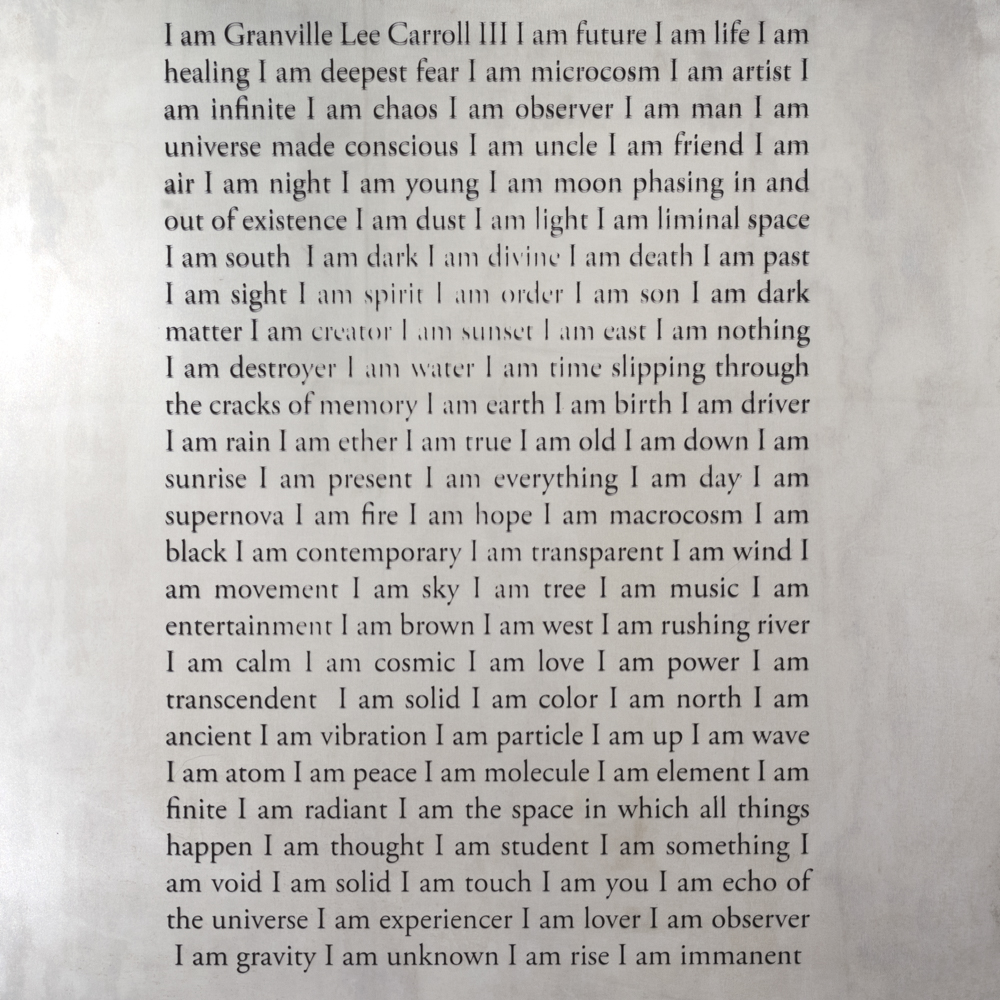

Granville Carroll is a visual artist currently based in Rochester, NY. Carroll holds an Associate of Art (2015) from Mesa Community College, a Bachelors of Fine Art (2018) in art photography from Arizona State University, and an Masters of Fine Art (2020) in photography and related media from the Rochester Institute of Technology. Carroll’s work is influenced by Afrofuturism and spirituality. Carroll reworks the physical world to address the possibility of a world beyond the material by combining multiple images into one. His work addresses issues of representation and identity construction. He questions who we are beyond the constructs of society and labels we define ourselves with. When our physical self dissolves who are we at our core? Carroll activates this space of questioning through the imaginary landscapes and portraits he constructs.

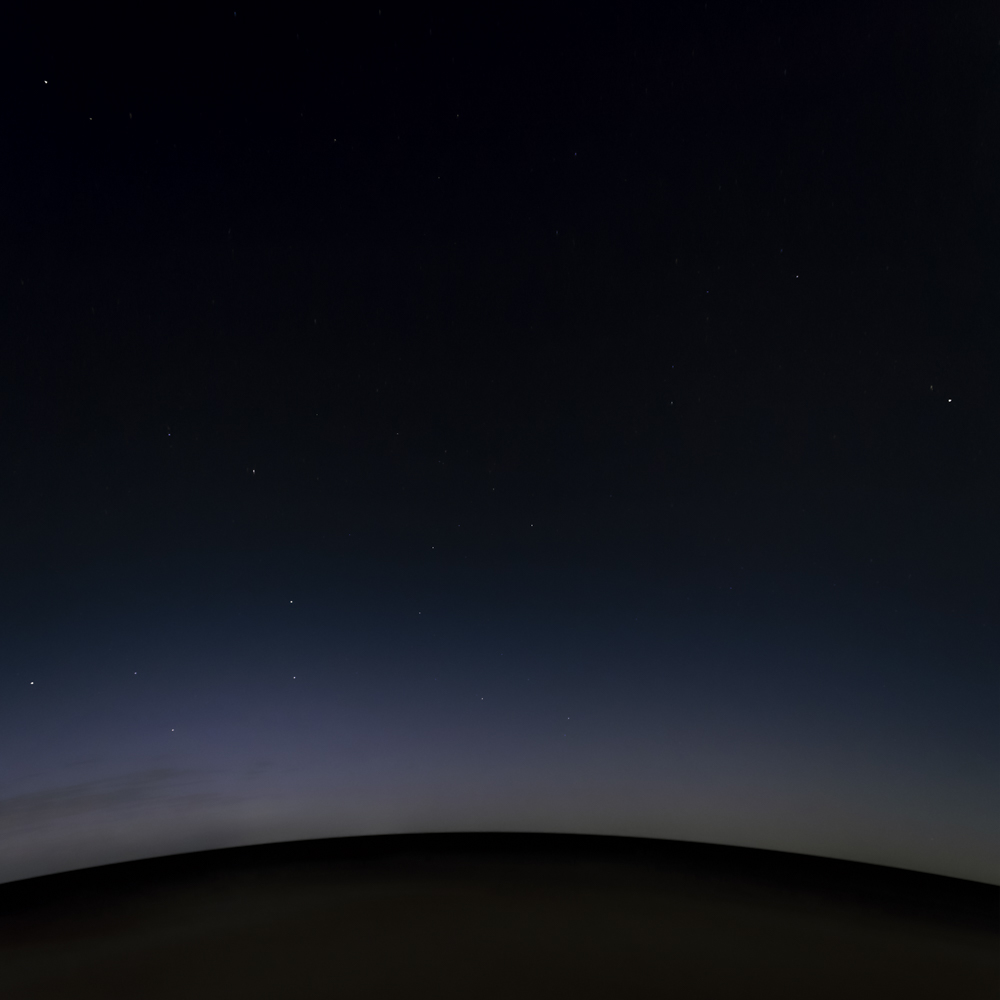

Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me

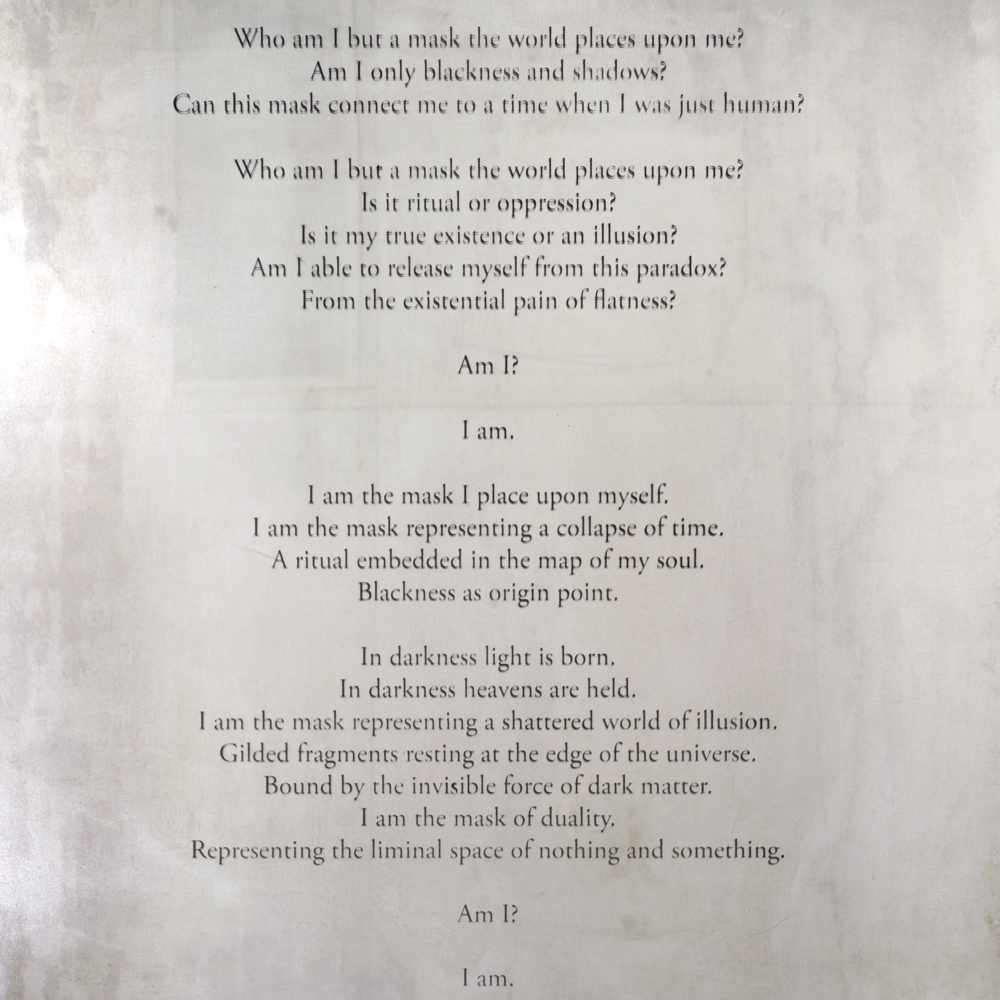

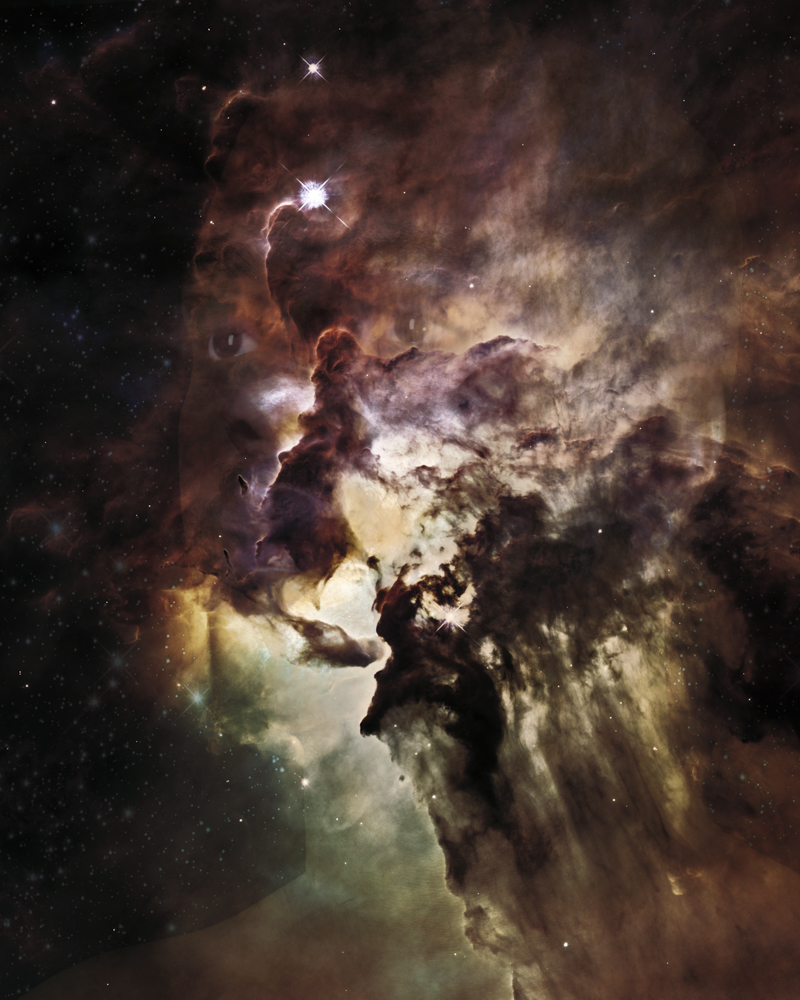

“Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me” is a photographic project examining identity construction on an individual, society, and cosmological level. It is a response to racial limitations and judgements thrust upon the African diaspora. I reimagine my identity through Afrofuturism by intersecting cosmology, philosophy, and spirituality. Using digital technology, I composite photographs to create new landscapes and self-portraits. The landscapes are my vision of the promised land; the ground references the physical world, the sky becomes a canvas for projection and imagination, and the horizon acts as a symbol for the liminal space between the physical and ethereal. They serve as points of rest and sanctuary. The portraits introduce a new way to envision my Black identity through the power of the universe. The theoretical concept of “liquid blackness” allows Blackness to be as fluid and unbounded as the cosmos. I construct a space where Blackness is immanent and expansive, using the Yoruba cosmological concept of ase and connecting it to the idea of dark matter; the force that holds the universe together. Ase is said to have come from Olodumare the Yoruba supreme deity, who is believed to be the source of creation. It is a force that breathes life into the universe bringing everything into existence, giving form to the formless and motion to the motionless. I look beyond the separation and limitation that occurs in racial stereotyping, positing that identity is more complex than just our physical representation.-Granville Carroll

The title of this series, Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me references the Song of Solomon. What’s your connection to the bible, your interpretation of that specific book and how it applies to your work?

I grew up in the Christian church, so the Bible was a part of my upbringing. As I grew up, I moved away from identifying with a specific religious ideology and began looking at the world more broadly. As I was doing research for my thesis I came across the verse “Look not upon me, because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me: my mother’s children were angry with me; they made me the keeper of the vineyards; but my own vineyard have I not kept.” (Song of Solomon 1:6). I was more concerned with the first part of the verse, “look not upon me, because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me.” How many times has a brown person walked into a space and the first thing that people notice about them is their race? Race is always at the forefront and obscures the essence of an individual. It creates a framework that denies the ability to construct an identity beyond this societal construct. I had been thinking a lot about the idea of racial categorization and how that limits or elevates the person being labelled. Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me emphasizes blackness as being touched by the sun’s light and grace and its power resonating beyond the surface of skin. I use this passage as a reference to how the sun darkens skin, brings forth life, and illuminates form. Thus, calling attention not only to my dark skin but the cosmic unboundedness that I possess. This body of work addresses the concerns I have with racial categorization and how I look beyond these false constructs to redefine my identity. Look not upon me because I am black, but look upon me for the life that I express, the joy that I can bring, and potential I possess. I am a black man but that is not all that I am.

What can you tell me about your journey in photography thus far? Has your interest in the medium always revolved around digital compositing? What about that process speaks to you?

When I picked up my first camera, I never imagined I would eventually follow a career path in the arts. I took my first photo class in community college just for fun and that’s where I found the magic in the medium. Initially I was interested in landscape and portrait photography. When I started out, I actually wanted to be a purist. I made minimal edits to my images aside from slight adjustments to color and light levels. I wanted my images to be a reflection of reality. All of that quickly changed. Photo manipulation was introduced to me early on when I took an intro to digital photography course. My professor gave us a multiple image assignment and taught us the basics of Photoshop. It was like magic to see how an image can be transformed. I like to think of my process as painting with photography. The single photograph is my blank canvas and then I build layer upon layer creating something entirely new and different. The images are given a new breath of life, it’s exhilarating to experience the transformation. I had the pleasure of working with Stephen Marc during my time at Arizona State University. He challenged me to shift reality to the way I see it, teaching me the symbolic meaning behind the additive and subtractive nature of the process. Jerry Uelsmann was quite an inspiration with my early work. Uelsmann believes photographs to be metaphors, acting as portals to one’s psyche. I like to explore what lies within the depths of the mind and how we can make sense of the external and internal worlds. The indexical nature of photography allows me to capture the world as I see it and its malleability allows me to enact my will on the image and bend it to my needs. Through this process I become the architect of my reality.

My working process is mainly digital, but I do like to experiment with other processes when I have the chance. I’ve worked with alternative photographic processes such as gum bichromate, platinum/palladium, Vandyke, cyanotype, wet plate collodion, and lumen prints. Often mixing the digital process with these 19th century processes.

When did you first discover the Afrofuturist aesthetic and ideology? Did it inform a previous way of artmaking for you? How so?

I first discovered Afrofuturism through one of my professors, Binh Dahn. I was showing him some new images I had constructed using self-portraiture, landscapes, and patterns and he asked if I had ever heard of Afrofuturism. I was completely unaware of its existence until that moment. I went home to research Afrofuturism and was astounded to see the connection between my work and the movement. My work fit right in with this way of making and thinking. Afrofuturism relies on the imagination, technology, and science-fiction. So, in a way no, my previous work was not informed by the specific movement, but also yes because it was influenced by the same values and ideals associated with Afrofuturism. My work is imaginative, hopeful, utopian, and has elements of science-fiction. It calls attention to the ethereal, ancient, and invisible forces of myth and legend. I grew up watching movies/shows related to science-fiction and magic. I explored the outdoors pondering the origins of the earth, its plants, animals, and humans. In undergrad I was really interested in sacred geometry and the symbolic forms that appear throughout the microcosm and macrocosm. What I love about Afrofuturism is the license to explore. There are no bounds to its expression, no rules for what it should look like. It is the values and ideology that reshapes our identities and leads to mental, emotional, and spiritual healing.

In your statement you mention the idea of “liquid blackness”. Could you tell me more about this theory and how it applies to your work?

Liquid blackness was founded by Alessandra Raengo and is a theory that studies blackness as aesthetics. This theory examines the fluidity of blackness and how it morphs and changes. In particular Raengo explores the sensorial expressions of blackness and its impact on American culture. She notes how the construction of race through the senses was imperative for whites to solidify stereotypes and to justify the unjust and heinous mistreatment of Africans and their descendants. This structure of blackness, as a negative expression, embedded itself within the fabric of our culture which remains present in our current cultural sphere. Raengo explains that it is everyone’s responsibility to be aware of their expressions of blackness. Liquid blackness was developed to recontextualize blackness as it is perceived through the senses. You can find a brief reading on the many ways blackness is redefined here: http://liquidblackness.com/lb-original-about-page/

I picked up on three descriptions which I find a direct connection to my art; unboundedness, vibration, and formlessness. Unboundedness is defined as being widespread and uncontainable, life blooms through the vigor and vibration of dark matter, and formlessness identifies blackness as filling all available space, taking on endless forms. I visualize blackness as being bold, powerful, and immanent to life. I connect blackness to the sublime of the cosmos. I seek to understand the origins of my blackness by connecting it to the origins of the universe. I use my body as a container of blackness allowing it to morph in different ways. I express the ideas of unboundedness, vibration, and formlessness to construct new spaces and weave a loose narrative telling a story of transformation.

Spiritually your work is very inclusive and draws reference from Christian ideas in addition to West African religion and philosophy. Why is this merging important to your way of art making and storytelling?

The knowledge of who my ancestors were, where they came from, what traditions and values they held are lost due to the displacement of Africans during the slave trade. Christianity replaced many of the indigenous religious and philosophical thought in Africa. By merging the two together I begin to make sense of the multiple worldviews I come from. The intersection of the two grew somewhat organically. I was reading Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi and immediately was thrust into a word filled with African culture and magic, specifically, Yoruba. I started researching Yoruba cosmology and found a striking resemblance to my own teachings in Christianity. Yoruba spirituality was dispersed globally during the slave trade. To save aspects of their culture, the Yoruba people imbued their ideas within the religions they were converted to. It now manifests in different iterations such as, Candomblé, Santeria, and Vodun, to name a few. The merging of various religious and spiritual thoughts is something that has been occurring for a long time. Personally, I challenge the Western perspective I have grown up with questioning the teachings of my past and cultural values. In doing so, I begin to build my own personal origin story and creation myth. It tells the story of where I come from and imagines a new frontier to explore. I don’t believe that one specific ideology has the monopoly in the truth. I draw inspiration from a number of spiritual thoughts to construct my identity and therefore how I think about and make art.

2020 has been a year of great societal shift with the spread of a global pandemic and a surge in the ongoing fight for racial equality. How have these events transformed your way of working?

A lot of my work already has themes of isolation and solitude running through them. Entering into quarantine was not a new experience for me. I went into a mode of reflection realizing how important it is to understand the difference in isolation and solitude. Isolation can be interpreted as being lonely and disconnected whereas solitude is about healing and reconnection. By adjusting our language to identify with a space of solitude we can begin to heal and address ourselves in new ways. The theme of solitude is constantly resurfacing for me. In my work I want to show people that looking within is not always scary but can be a beautiful and life changing process. The pandemic forced me to slow down and truly understand what I value as an artist and what messages I want to convey.

Current events confirm my viewpoint on race and how I can use art to combat it. One of my professors in grad school identified me as a photographic healer. I’ve been meditating on that statement for over a year now wondering how this may be true. I have always believed art to be healing but wasn’t sure how to express it. Now, more than ever, I understand the power of image making and the impact it has on how we see ourselves and others. The fight for racial equality is right in line with my most recent project, Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me. When I started graduate school in 2018, I was confronted with speaking about the topics of race and representation. I was reluctant to do so because it felt limiting. I did not want to be classified simply as a “black artist.” As a black man who takes self-portraits I started to realize how the first thing people see is my blackness. For the past two years I have been researching race as a construct and how to move beyond it. I believe racial categorization to be destructive and limiting. I see this playing out in our fight for equality right now. The black community is tired of being demonized, mistreated, unheard. That pain is manifesting itself in the form of protest and education and art. Honestly, it has been for a long time, but it is only now that it is at the center of attention. Racial labelling is archaic and serves no other purpose than to uplift whiteness to sit at the apex of our society. That is not to say that ethnicity and culture shouldn’t be valued, race and ethnicity are not the same. I’ve been meditating on my research on race and its effect on society, thinking about how it creates the illusion of separation and deepens the divide. Race defines who we are before we even get a chance to explore the essence of ourselves. I wanted to create a body of work that celebrates blackness but also speaks to the depths and complexities of it beyond skin color.

Macaulay Lerman was born in the Spring in Southern California and raised in New England. As a young adult he traveled throughout the US and Canada hitchhiking, hopping freight trains, and driving his camper van. While Lerman rarely carried a camera during this time, he developed a practice of documentary storytelling through extensive journaling. To this day he remains fascinated by fringe communities and alternative ways of living, perceiving, and being in the world. While his process is largely ethnographic, in the sense that he immerses himself in the worlds he depicts, he is far more interested in emotional realities than hardlined physical truths. Above all else he values dreams and memory. A photograph exists somewhere between the two and this is why he is drawn to the medium. Lerman earned his BFA in Photography and Documentary Studies from Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont. Since then he has shot for a variety of organizations including the Slate Valley Museum and the Vermont Folklife Center. His work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group exhibitions, and featured in publications including It’s Nice That and Anywhere BLVD. Lerman currently resides in Burlington Vermont where he is an active member of the Wishbone Artist Collective.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024

-

Interview with Peah Guilmoth: The Search for Beauty and EscapeFebruary 23rd, 2024

-

Brice Bischoff: How CloseFebruary 18th, 2024