Photographers on Photographers: Lorenzo Triburgo in conversation with Jasmine Murrell

© Jasmine Murrell, #05 (the Power Source), (acrylic, canvas), 2019

Jasmine Murrell and I were both 2019 CCNY/Baxter St Workspace Residents and I was immediately fascinated by her practice. Jasmine makes sculptures, video art, photographs, sound art, performances – and she does all of these things well and then combines them in the most thoughtfully provoking ways. I have seen Jasmine make wild sculptures, turn them into a social practice project for which she then creates conceptual photographs — then combine all of the aesthetics and ideas related to these modes of creation for an installation of all new objects born from the images, the social practice, and the sculptures. Brilliant. I will also reflect that during our first conversation at Baxter, Jasmine already started thinking of artists who I might like to be friends with and ways that she could help me bring the vision for my residency into a reality. I have learned since then that having a conversation with Jasmine is a treasure of an experience. So, I decided to have a conversation with her for this piece.

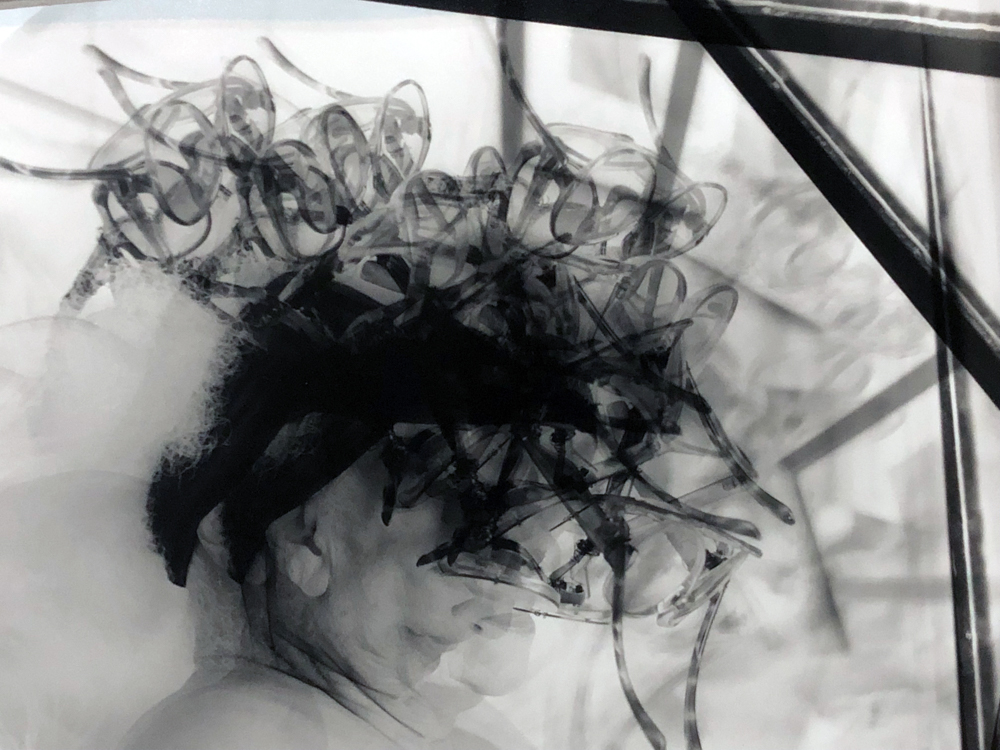

In The Unknown One (Reimagining the singular as a collection of One) artist Jasmine Murrell pays homage to the oldest members of her community. Murrell reframes the traditional portrait using video, photography, printmaking, and sculpture, to present a more inclusive alternative to the classic/postmodern nude figure in contemporary art. Murrell draws from an eclectic range of aesthetic and theoretical influences ranging from abstraction, feminism, post-colonialism, indigenous artisans, Afro-Futurism, Négritude, magic realism, Dadaism, the science fiction, and musical pieces such as those by visionary jazz composer Sun Ra.

The exhibition features wall mounted sculptures created through layering photographs of the female body (placed on a variety of substrates including canvas, paper, wood, and fabric) with found objects, and marking their surfaces with silkscreen and paint. The subjects of the photographs are women adorned in headdresses sculpted by Murrell. She describes the headdress as a method of psychological transformation, and the women as being connected through a larger consciousness in their ability to work against adversity.

© Jasmine Murrell, Black Movement (silver gelatin), 2019

Lorenzo Triburgo: I always start conversations with “Hi, how are you?”, and it should be “How are you holding up?” Like, seriously, how are you doing?

Jasmine Murrell: Today I’m doing great. [Laughs] At this very moment I’m doing great.

LT: Good.

JM: How about you?

LT: Yeah, same. Today- the last couple of days actually- have been pretty good. It’s hard to define why some days feel so much harder. I feel sort of unmoored or ungrounded since the pandemic…but some days, you know, I feel more grounded, more able to face things, more full of hope for the uprisings.

JM: Yeah, I think it’s just the unknown- of not only our precious life, but also what’s happening with our jobs and the economy. I feel a lot better than in the beginning, but I think the uncertainty makes it stressful. I think as human beings we want to control things- like the whole ecosystem- and we kind of feel superior, that we can change or control things to be the way we want. But you know, it’s not always so.

LT: And I feel like the pandemic has made me question so many things and really think about my art practice. For me, it’s this idea of trying to live outside of a capitalist structure and creating a life for myself…like, the lifestyle of an artist and the sacrifices we have to make and what that means in terms of an act of resistance. Does that resonate with you?

JM: No definitely, it’s so hard and I completely agree that being an artist is kind of like an act of resistance. But then, at the same time, I feel like it is such a privilege. For me, in America, and to go to art school- it is a privilege.

It doesn’t mean that you’re not an artist [if you don’t go to art school]…like, I think of Robert Blackburn or these self-taught artists that use that as an act of resistance. And I think about different cultures around the world and the way art is used as a way of resistance, and how even just having education is a privilege… I do a lot of collaborations with all different types of people in different parts of the world and it’s really humbling because, you know, even just having water — just running water…

So to be an artist, it is an act of resistance. But on the other side I remember when I first went to undergrad and my father came to visit me and he was such an artist, he used to just kind of make things but he never felt in his wildest dreams that he would ever be able to pursue art because he was always trying to provide you know, substance and food, so it always comes back to having access to some – thing.

I remember looking at him, he was just like in an awakening, like, “Wow, this is a possibility. My daughter is going to be able to pursue art.” But there are some artists, they didn’t have the privilege of going to art school, and art was this calling for them. Several of my friends with the queer collective “How Do You Say Yam in African?” (YAMs for short) were completely like that. They were some of the most amazing artists and they literally were living in mostly poverty. So yeah, it’s like everything is kind of a mixture of gray, you know? [Chuckles/Smiles]

© Jasmine Murrell, Dell, 2019

LT: Totally, yes. So I want to talk to you about your show at Baxter, The Unknown One. I would love to talk about your ideas behind the layering; the installation of it was gorgeous. I love the combination of some images hanging as straight photographs alongside these layered canvases with printed images and other tactile materials- I thought that combination was really smart, and it was also just pleasing to be in that space that you created.

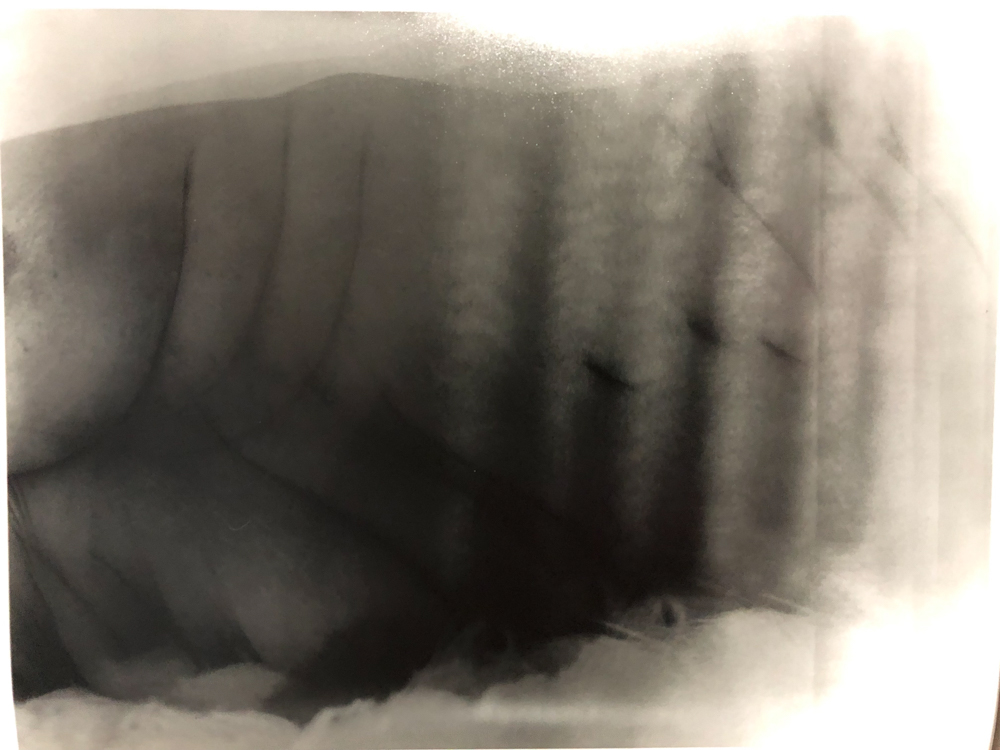

JM: Oh thank you. I mean, it was really challenging to merge the two. For the pieces that were not framed I was really just interested in skins. This idea that we have become so much about the surface and we don’t have a chance to really see so much that is just beyond the surface. I feel like that even with a lot of art, because we’re looking at them through boxes and we are not really present, it’s changing the way art is seen, the way art is supported, and so I wanted to make something that was almost alive. I wanted to think about them as skins and layered skins that, you know, you have this top surface, but the substance of the piece is really unknown. That’s why it was “The Unknown One.” It’s really kind of like the foundation of all my work is just thinking about that collective of DNA — that collective, ancestral bodies are part of you.

LT: Actually, one of the first times we had a chance to talk, at Baxter, you mentioned your work with the collective, and I think the U.S. is so individualistic- we are seeing that now, of course, with these people not wearing masks. It’s the toxicity of our hyper-individualistic society- and I think it’s radical to think about collectivity, collectives, and collaboration. I’m wondering how that made its way into your life and your thinking. Is it something that has always been part of your life? Where does that sensibility come from for you?

JM: Well, I think that without collectives black people would never have been able to survive in some communities; collective economics, collectively working together for a common goal. Growing up in Detroit there were a lot of these kind of marginalized or subcultures of interests and art collectives. AfriCobra was also nearby in Chicago, so I was always surrounded by black art collectives.

And, for me, being in New York and going through an institution where there weren’t a lot of people that looked like me — there was basically no representation of black professors [at Parsons], maybe one or two, and hardly any that were female, especially doing sculpture or mixed media — it was my saving grace to be a part of a black queer collective.

Dealing with a school where so much art history and perspectives were completely erased was very traumatizing. For me to come from Detroit, immersed in so much history — not just of Africa or the Caribbean, but also of African American influence on art — to New York, which was supposed to be this multicultural mecca…there were just so many [artists] that no one knew, except for maybe Basquiat, you know?

They [the YAMs] spiritually, emotionally, in every capacity- even financially- gave me the support I needed. I literally borrowed a camera for the last 15 years; I didn’t own one until the Baxter Street and Bronx Museum residencies. All of my resources went into trying to create space for survival and collective economics, making sure we had a home and, after that, my art materials.

© Jasmine Murrell, Nefra, 2019 (canvas)

LT: How did you all find each other and get started?

JM: The group was actually much older, starting in DUMBO in the early 90s or maybe even earlier in the 80s, but one of my best friends, Dominika [Ksel] introduced me to the group in grad school. I also met Sienna [Shields] around that time and she became one of my cosmic sisters. She’s one of the most brilliant artists to me. She brought all of us together to do a project, but I felt like the project wasn’t as important as the process of making the project.

LT: Can you talk about that a little bit, the process and the project?

JM: When it started we were making video operas and it was just a bunch of folks collectively coming together to just create things and feed off each other’s creativity. People would visit from different parts of the world and we would just hang out. Sometimes it would be like, “We gotta go shoot, we’re gonna do a film,” and sometimes it was just like a studio party. It was very free. We weren’t always together at the same time; we were collectively working on different things, from sound to installation to sculpture to performance. It was any kind of artist you could think of- performance artist, visual artist, sound artist- working together. There were also writers in the group. And it was the only space where I felt like people had different kinds of superpowers or abilities, that communicated in different ways, and it was understood. It was really difficult to show that, but the end result was films, videos- The Wayblack Machine- which was like an archive of all of these different articles and images from Twitter several years ago about police brutality and violence on the black body. There were so many pieces to it, our installations. Then, what most people know about was [turning down an invitation to] the Whitney Biennial.

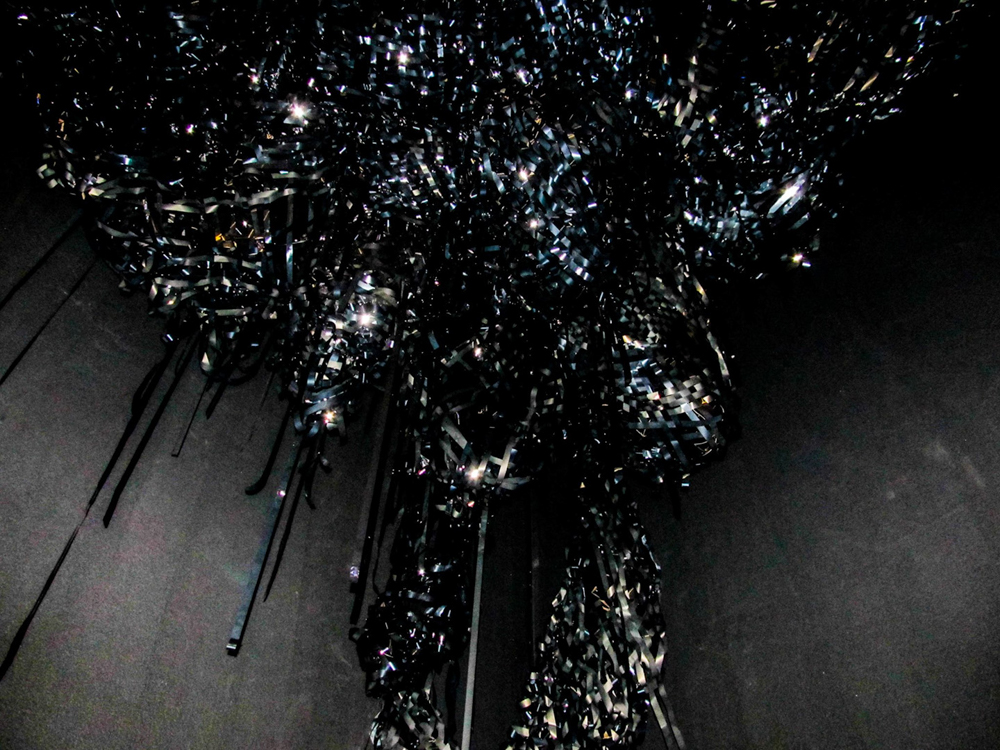

© Jasmine Murrell, Immortal Uterus, (VHS Tape, Wire, Light, Sound equipment, performances of Kelsey Lu inside the Uterus), 30x40x 20′, 2012-2020

They [the YAMs] also helped me on my projects like Immortal Uterus, which is a 30×40’ woven installation of film I didn’t have enough money to even buy the VHS tape and, again, collectively people put together money, and then they helped me weave literally thousands and thousands of yards of tape. Even during the pandemic, they were a huge reason why I was able to feed myself. You know what I mean? They’re just…I could cry, it’s like family, you know, so fragile. So many black trans and gay men and women, just queer, queer women that are dealing with so much abuse in their daily life — not even including with the police — but just in society, and they are the most loving and giving. I am a queer woman, too. I’m married to a man but I am a queer woman. You know, I just think that some of the things that are the most precious in our communities, in our life, we take for granted. And the people we take for granted, we don’t realize how much they’re really holding us, and holding up the community from just snapping or breaking.

LT: It sounds like that they’re still an important part of your life.

JM: Oh yeah, definitely. And I think like with all families you’re gonna disagree, and I think that’s what I have an issue with in terms of social media. I’m really fearful that there is no space for people to disagree. You have to “like,” and you can’t have a discussion. And for me, disagreeing and having a discussion is real growth and real understanding. It’s not a process that’s going to be comfortable — any transformation is very very uncomfortable- and so that’s what I get worried about, that we don’t have enough spaces for human beings to have a different point of view.

LT: Yeah. So speaking of the YAMs, can we go back to the Whitney Biennial? Are you open to talking about the YAMs’ decision to turn down an invitation to the Whitney Biennial?

JM: Really, Sienna [Shields] was the one. That was really her project, and she wanted to have a conversation about the presence of blackness in institutions like the Whitney. I feel like she’s made a huge impact now, today. She was doing this, like, six years ago when there really weren’t a lot of these conversations happening. And when the chosen few black people are chosen, they’re happy. They take it, and then they ride to glory…but she chose another way, and she’s kind of been blacklisted for doing that.

I was a huge fan of David Hammons, and I will always remember his piece — was it the Whitney or the Guggenheim? — when he did a massive portrait of Jesse Jackson and they were like, “No.” And then he painted the face white, and then it was like, “Yeah.” But the institutions…they knew. So I really wanted to have that dialogue within the institution, but it would not have been as impactful as what Sienna and many of the YAMs saw [as the right direction]. I think her point was really to bring attention to it, and I think she did it very well. She also did this fantastic piece, and she didn’t like the idea that people were going to pay to go see this opera and the money was going back into this kind of institution. Sienna was a mastermind of trying to create a collective economics outside of these white-led institutions, and I see so many artists and art collectives I can tell were influenced by that project, which she started.

Now I think we are preparing for another exhibition and, you know, we go back and forth. Some artists go off and do their own thing and then come back together and do projects- it’s like breathing- you go out and come back in.

© Jasmine Murrell, Madonna, 2019

LT: It also kind of goes back to this idea of the artist as this individual genius…it’s such a false construct, and it’s so based in racist sexism. Basically, like, “Oh yeah, the individual genius is who? It’s this white guy, right?” and he’s never had help from anyone and definitely never had any ideas from anyone else, and definitely not from anyone besides white guys who lived before him. And in the history of photography there’re so many ‘effing men who don’t give credit to their girlfriends or wives, or younger female assistants, right? So it’s like, eff that. You know, I got the Baxter residency, and Sarah and I were working on the project together and I’m like, “You know what, this is a collaboration and we need to acknowledge that.” So, yeah.

JM: That’s beautiful.

LT: Don’t even get me started.

JM: [Laughing]

LT: This idea of working inside the institution vs outside the institution kind of goes back to this question of, “How radical can I be as an artist, and what am I willing to give up?” And giving up an opportunity is a whole ‘nother level of radical act and statement. I think that’s so impressive and powerful. Thinking about sacrifices, we think about these material things…but to sacrifice opportunity is next level.

JM: Definitely. Definitely. I feel so exhausted, to be honest. I understand and I can relate but I guess right now I’m at a place of just trying to find radical joy.

LT: Yeah yeah yeah.

JM: In the midst of chaos — and there was always chaos — I remember asking my grandmother when she was towards the end of her life, like, “God, when is it going to get easier? When is it going to get better?” and she’s like, “Life is a fight.” And it was like you have to fight for everything. So right now I’m just so tired from fighting in some capacity. I fight for the work. I definitely fight for the work. I put all my energy into making and thinking about the work. There’s so much to be said about the work but then, in saying that, at the same time I’m thinking about the process over the product because my life can’t be solely just about surviving and fighting. In these kind of moments, even with your partner, these collaborations, you’re trying to figure out “How can I do this powerful work with help and with joy and comfort?” Comfort is really dangerous too, as you know. It’s very very dangerous, and it perpetuates a lot of thinking- of whiteness and of hierarchies. And sometimes in comfort you cannot have empathy for other people who have less or more, that are not able to pass for certain privileges. On many levels comfort is just horrendous, ignorance and not reading, not constantly educating yourself.

LT: Complacency, right? Comfort and complacency. “Well I’m good now, so I’m just gonna call it a day…for the rest of my life.” [Laughs]

JM: [Laughs] Exactly. Yeah, complacency, perfect. It can be dangerous, but I’m trying to find that balance.

LT: Yeah, you don’t need to suffer…or at least not intentionally, right? It’s like, if we can relieve some of the suffering for ourselves, that’s also really important.

© Jasmine Murrell, Grandma Full, (mixed media on canvas), 2020

JM: Definitely, and I think that at the same time we’re kind of addicted to a certain type of abuse.

LT: Ah. [Sighs] Yeah.

JM: We’re attracted to it all the time, a certain narrative of that. And it’s in our consciousness, so even in erasing it, it’s always there. So I’m trying to break out of that, because I think that’s also part of the colonizer fantasy of keeping us in our place. Even when I think about sex, our sexuality, and fully expressing our beauty, I feel like it’s so much attached to torture, and there’s so much dysfunction.

I mean, the first film I ever shot, like real film, was kind of a reenactment of an ancient time in China, the first dildo and what lesbian women would use, like using tofu and so.

LT: Wait, and using what?

JM: Using tofu.

LT: Oh wow.

JM: I’m thinking about all types of tools you can use for pleasure, and I’m just really curious about it. For years I worked with a lot of seniors whose partners had died. They would tell me in intimate conversations that, as they got older, their sense of touch and everything actually got more sensitive, especially for women. It’s very different for men, but for women everything is kind of still working. It’s actually even stronger. And so, what do you do?

You know, I’ve seen older women in my family as they are aging, they almost always outlive their husbands or regardless of whatever gender their partner is, if they are still alive and their partner is not, and they don’t have someone, most of them do crave a touch. That’s why sometimes they would go to the doctor just for someone to rub on their legs and it’s really common, even with men. So I think that we have so many negative narratives about our sexuality and about our sex and our needs that are kind of related to really poisonous religious propaganda.

© Jasmine Murrell, Walking Time Travelers 2019

LT: Absolutely! So, I don’t want to be like, “So what are you doing now?” or “What’s next?” because those questions are sort of based on this idea that we have to be producing all the time, but what does your practice look like and feel like right now?

JM: [Smiles] I’m actually getting ready for a show! It’s at the Alabama Contemporary Art Center and I’m doing a combination of my dirt sculptures and videos. I’m animating many of the photographs from the exhibition at Baxter street and turning them into these mythical stories around historical facts. I’m doing a lot of research around interspecies communication from different time periods, present and past, and how we used to collaborate and communicate and work with other species in a way that we maybe do more so now with computers and non-living things. I’m really fascinated by that right now. And evolution has kind of been deeply influenced by those relationships.

LT: Is this kind of going back to this idea from The Unknown One of collective memory and knowledge that’s passed on through generations?

JM: Definitely. I think we think of environmentalists as mostly white, and it’s just not the case. I really feel like many things that we would consider ancient are really going to be our saving grace to get us out of the mess that we’re in now. I’m not saying that it’s exotic or that it’s perfect. It’s not and there’re definitely a lot of issues, probably far worse than now, but there were some things that were unbelievable to me. Like, I believe it’s in Mozambique, where a group communicates with these birds through a whistle in order to find honey in a tree. The bird can’t get to the honey- a human has to dig it out of the tree. And then the part that the human likes, the honey…the bird likes the other part.

LT: [Facial Expression = Wow]

JM: Yeah, and there’s millions of other examples. I’m just so curious about that. So for the piece that I’m going to be recording a lot of things, doing sound, collaborating with some of the YAMs, literally recording the sounds from certain plants and putting it in the video.

© Jasmine Murrell, Mother of Mother’s, 2019

LT: When is the show?

JM: It’s in the beginning of September. What about you? Tell me about your show! [Hands raised in the air] Your show at Baxter’s coming up!! Woohooo!

LT: [Laughing] The longest anticipated show of all time! It was supposed to be in April, but it will be in October! All the pictures are finished for the show, so that’s really exciting.

JM: [Smiles big]

LT: I know! The last day we shot was super early in the morning the day before the lifeguards started because, you know, technically being nude on Riis beach is illegal…

JM: [Laughs]

LT: Yeah, and we weren’t looking to get arrested or fined. [Laughs] And now we are just working on installation ideas. So Shimmer Shimmer will be opening October 7th!

JM: I know it’s going to be amazing. I can’t wait.

LT: Aww thanks. [Big smiles]

Jasmine Murrell is a New York-based interdisciplinary visual artist that employs several different mediums to create sculptures, painting, photography, performance, installations, and films that blur the line between history and mythology. Her works have been exhibited nationally and internationally for the past decade in venues such as the Museum of Contemporary Art and Bronx Museum, Museum Contemporary Art Chicago, Whitney Museum, African-American Museum of Art, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art and International Museum of Photography, and non-traditional institutions. Works have been included in the book MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora and the New York Times, Time, Hyperallergic, The Detroit Times, and several other publications.

She has an exhibition opening in early September 2020 at the Alabama Center for Contemporary Art.

Follow her on Instagram: @jasminemurrell

© Lorenzo Triburgo, Venus, 2020

Lorenzo Triburgo is a Brooklyn-based artist employing performance, photography, video, and audio to cast a critical lens on notions of the “natural,” the construct of gender, and the politics of queer representation.

Lorenzo has artworks in the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL, and Portland Art Museum in Portland, OR. They have exhibited and lectured in cities throughout the U.S., Europe, and Asia, including Bruce Silverstein, NYC; Photoforum Pasquart, Biel, Switzerland; Kunst und Kulturhaus, Berne, Switzerland; the Dutch Trading Post, Nagasaki, Japan; The Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; Magazzini del Sale di Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy; and Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, as the first place winner of the international Pride Photo Award.

Lorenzo was awarded a Workspace Residency at the Camera Club of New York at Baxter Street in 2019 and is currently a 2020 AIM Fellow at the Bronx Museum of the Arts.

Lorenzo holds a BA from New York University in Photography and Gender Studies and an MFA in Photography and Related Media from the School of Visual Arts. Lorenzo teaches Critical Theory, Art, and Gender Studies for Oregon State University’s online campus.

Lorenzo’s solo exhibition, Shimmer Shimmer, will open October 7, 2020 at CCNY/Baxter St.

Follow Lorenzo on Instagram: @lorenzotriburgo

© Lorenzo Triburgo, from Monumental Resistance Stonewall, 2018

© Lorenzo Triburgo, from Monumental Resistance Stonewall, 2018

© Lorenzo Triburgo, from the series Policing Gender, 2015

© Lorenzo Triburgo, from the series Transportraits, 2012

© Lorenzo Triburgo, from the series Transportraits, 2009

© Lorenzo Triburgo, from the series Transportraits, 2009

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

Love and Loss in the Cosmos: Valeria Sestua In Conversation with Vicente IsaíasMarch 19th, 2024