América Latina Week: Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira

This interview was written with the kind help of and in conjunction with Elena Gálvez Mancilla – Mexican historian and sociologist; a researcher on the Amazon and indigenous culture, interested in the image as a historical source, photography enthusiast and environmental activist. The post is featured in both English and Spanish. The Spanish version follows the English.

I never want to stop looking at these photographs. Nothing stays still, their movement occupies my senses. Every image occurs as if it were a distant memory before a forced exile from water, mountains, nature and the knowledge of past lives. As if they were from another time and space and yet, I can feel them on my skin.

I do have to admit that Karen’s photographs make me wildly happy. There is a sense of play, discovery, care and consciousness. The possibility of coexisting with all living species is tangible when you are one and the same with nature. Everything she’s learnt from the wise women and men from the Andes and the Amazon inhabits these photographs. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do!

Karen Miranda Rivadeneira is an Ecuadorian-American artist, whose work focuses on memory, ecology and trance states through collaborative processes and personal narratives.

Following these interests, she has collaborated with her relatives to create photo-based projects, videos and performances. She has worked extensively with indigenous communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon, in the Andean Mountains and more recently in the American Southwest.

She has exhibited widely among places, The Portrait gallery at the Smithsonian in DC, The Americas Society, and numerous solo shows across the country. She has participated in the Musee Quai du Branly biennial and received their fellowship in 2017.

In 18’/19’ she was nominated for Prix Pictet on the theme of Hope, nominated for The Foam Paul Huff Award, she was a finalist at The Rolex Mentor & Protégé initiative by Carrie Mae Weems, and was shortlisted for the Hariban Award.

Her first monograph Other Stories/Historias Bravas was published by Autograph ABP in 18’, the preface was written by the seminal writer Alanna Lockward.

She has been invited to the BRIC and Woodstock residency in the summer of 2020.

Currently, she is a master mentor for the Women Photograph mentorship program and is a recipient of the WeWomen award.

Meda is fictitious;

As in its Latin root: to make by hand; made of clay; to earthen.

It pertains to the imagination, to the realm of dark creative force.

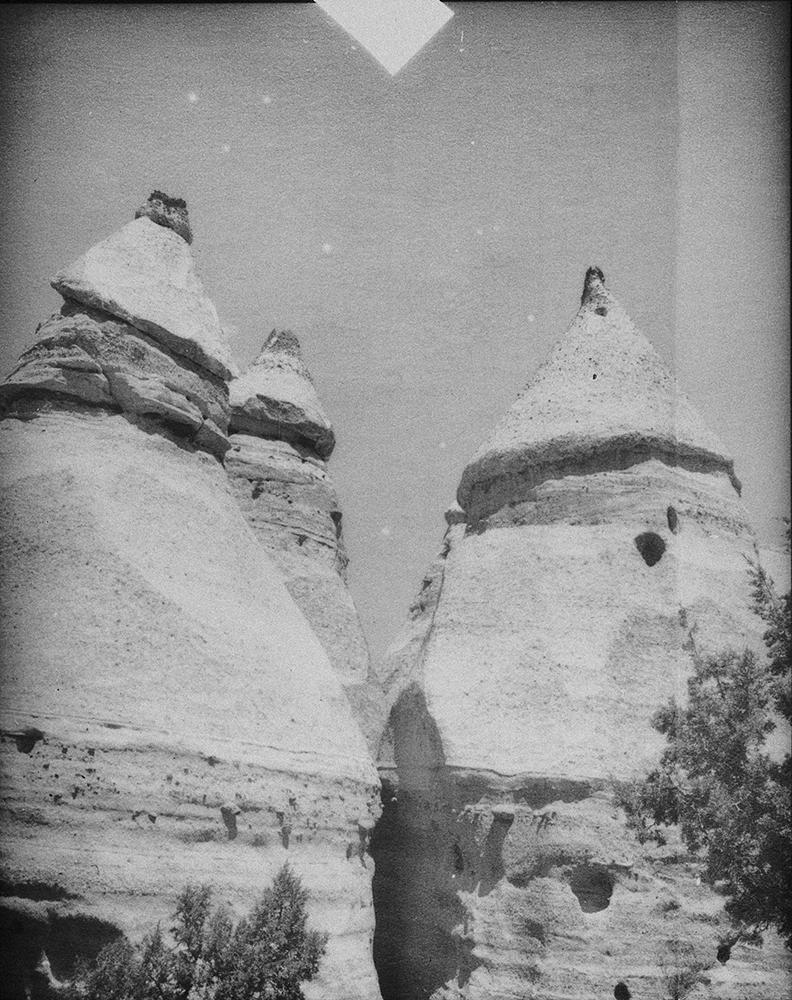

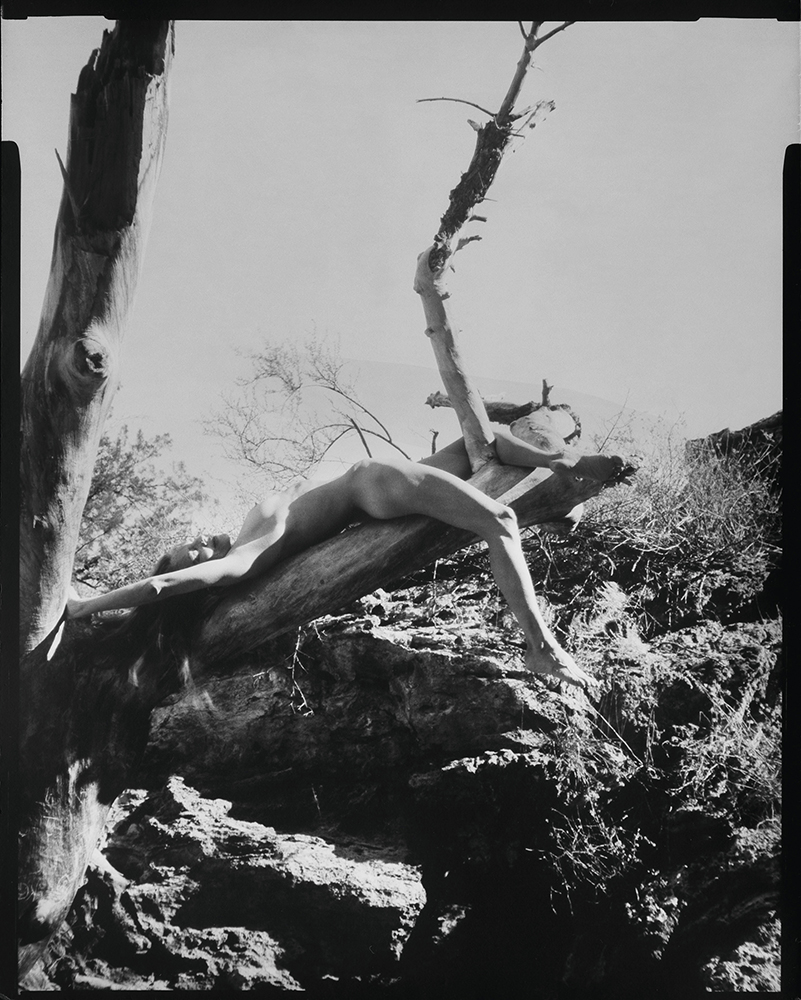

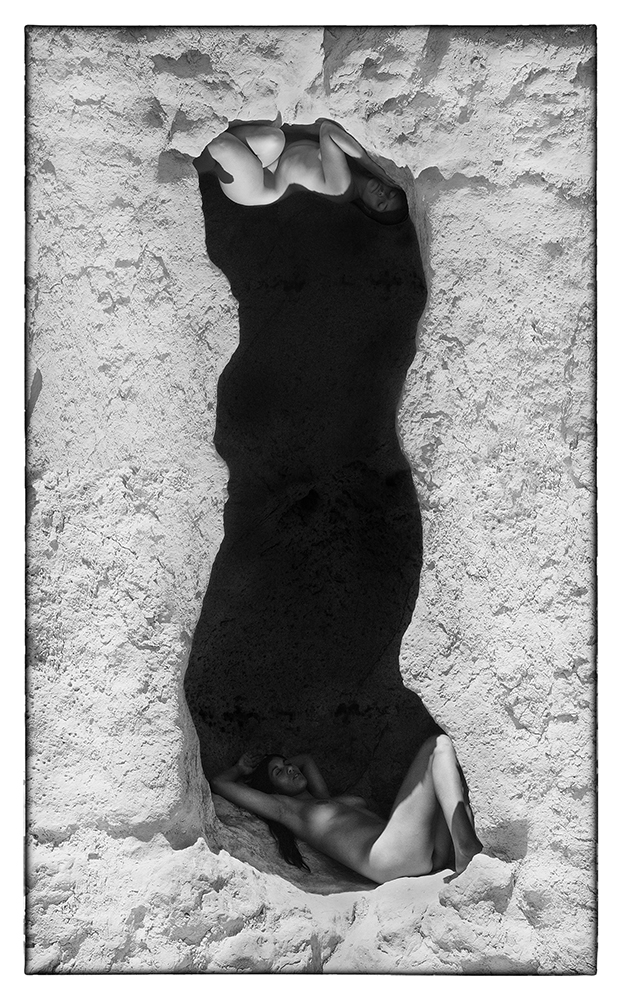

Informed by the southwest landscape where I lived, these images explore our relation to nature from the principle of myth and memory embedded in the body as the first land and the land as the first body.

To talk about the desert is to speak of water, its vestige exposing a tactile earth story, what does it mean for the psyche located in myths and in the memory that lives in the skin? In the languages of the Original people, Iyurina, ya sankofa; to remember by contemplating the land.

Deep in the mind of every living human, there are memories that can be traced back to millions of years and they can be activated under specific sounds, patterns, and images; ancient cosmologies shaped by geography, dust and blood. I seek a relation to nature that is spontaneous, collaborative and non-binary. Matriarchal sustenance birthed from transformation, pain and power. What I capture and encounter in these women is their relation to the body as the first land that we live in, which is also a land that bleeds. Photography has the ability to confront illusion: as both, a layering subjective process and as a raw direct experience.

We live in tumultuous times, contemplating the land is contemplating our origin and also where we are heading. MEDA is an anthology of the essentiality of intersectional storytelling, blood memory, a celebration of resilience, and our increasing need for a new paradigm.

How did you start doing photography? What is your process?

I began with painting and performance. However, when I was living in Guayaquil, I started using the camera as a tool to capture what I saw in order to understand the world. I think that there are many creative people but we cannot all paint, draw and sculpt; thus, our relation with art becomes blocked because of the lack of ability. Whereas with photography, the camera allows us to connect with our creativity.

That is how it all began, I was in Guayaquil, doing photography and working as a photojournalist for “El Comercio”. There weren’t any women photographers, they were al 50+-year-old men. At the time, I was a rare creature to them; a woman, tiny. Compared to them, I was different.

Later, I became very interested in the Amazon; travelling to that part of the country, while living on the coast, was a different and distant hemisphere. I was 19 and it was the first time I was travelling on my own. Getting there was an adventure and an experience in itself.

Finally, I was given the opportunity to travel and study photojournalism in Denmark; it lasted a year. Six months studying and the rest of the time I travelled and did photography with the people I’d met.

Who are the artists or people who have had an influence on your photographic work?

The beginning of one’s love for photography is quite a memorable one. Even if I do not follow the same line of work, the genius and ingeniousness of Graciela Iturbide were of great influence. She was one of the very first photographers whom I admired. Another important influence was Adriana Lestido and her work on women’s lives, daughters and mothers, prison labour; they are phenomenal. Those were important inspirational sources, I really love photography made by Latin American women. Naturally, that’s what I was drawn to.

Then, in the contemporary arts, there is Marina Abramović. Her work was of great influence when I was just starting. Now, I feel it is a lot more difficult to decide. There are so many people, from different ages and countries.

What inspires you about Latin America?

I like everything about Latin America; everything, everything, everything… Breathing in, the colours, the people, even the proximity of people on the bus to hear their accents; it makes me very nostalgic and I get tears in my eyes with the thought of it. Every time I go back to Ecuador, I wish I’d live there again. But I want to be honest too, there are many issues in Latin America; violence, lack of equality, etc. However, I think that what strikes me the most is the fighting spirit and mindset; “everything can go wrong but we keep on”.

Have you developed any new projects during the pandemic?

I’m working with video and performance, highlighting geopolitical and geopoetical aspects of reality. Now that I do not have the opportunity to travel to Ecuador, I have tried to grow from a personal space. I have an important nexus with nature and the ecosystem and I want to address this without recurring to indigenist discourses. Sometimes, we think that the answers to our processes are on the outside, but there is no need to do it as everyone else does it, the answers are on the inside.

Meda, your last photographic project, is so compelling… I admire how you have portrayed a dialogue between the body and nature. Could you explain how it was developed?

Meda is really about something quite simple, the body as the first land and land as the first body. There is also a personal environmental concern. I lived in New Mexico, where you can see the lack of water’s impact on the territory. It’s mostly a desert but shapes on the land show the memory of a different existence, it’s become so different now.

“Iyurina” is a Kichwa concept that means: Understanding our present through the contemplation of the land. I was interested in questioning my own actions. What am I doing, as a human, for the earth? How do my actions impact our habitat? Overall, the same question from a different perspective: How does the earth influence and impact me?

There is an important component of contemplation and analysis regarding the body’s connectivity – the wisdom it has acquired over a 30.000-year process. Meda explores the many possible ways of activating our innate wisdom through nature. While speaking to people who were going to be in the photographs, I generated questions for them: How would you interact with the earth if you were touching it for the first time? Each and every one of them reflected upon their proximity to the land through touch and their own bodies.

Meda was selected as the project’s title, not because of the thought of a specific etymology but because the word came to me. When I think about a project’s title, I find myself analysing and resignifying words. Later, when I researched the word’s etymology, I learned that it means fictitious. When searching for the etymology of fictitious, I learned it means creating with clay, creating with our hands. Thus, the term seemed adequate.

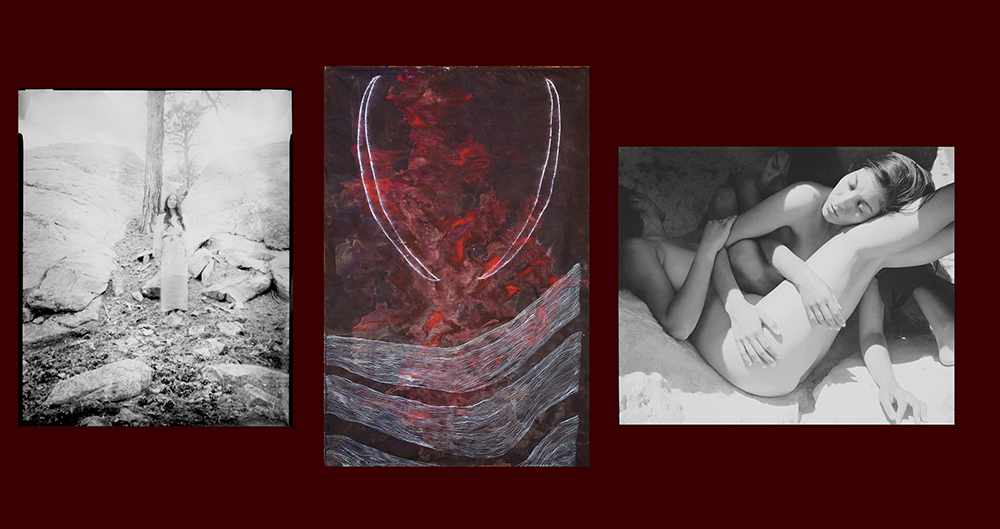

©Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira, Spider-Woman

What does ritual mean and how can you represent it?

That is what I am researching now. Rites or rituals are a means for changing the paradigm under which we are living. Nowadays, there is no time for silence, connecting with the earth and water, eros – pleasurable moments for oneself. There is no space for that in modern life. Ideas on rituals, resting and our relation to the earth are ancient; they are innate to humanity and we should try to rescue these practices.

What is spirituality’s role in your photographic work?

Spirituality is what infuses and surrounds my work, perhaps because of how I have lived and what I have learned. It has become part of how I reflect on my actions.

©Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira, She Sees Seashells

Elena: What you have said reminded me a lot about indigenous Maya communities from Mexico, where I come from. They say that the past is never to be seen looking backwards but it is in front of us. They take a present, ever returning wisdom into account. I can see that same purpose in your work. I also see the tearing of photography’s historical mission, documenting what is true.

There is a reservoir of symbols in your images; women, territory. They are very specific and yet, they communicate something universal. How do you select those sites and symbols?

I select them by thinking about how the experience of going to each site will teach me something that is absolutely essential about life. Part of my photographic work is co-creating with the universe. It has never been useful to work through imposition, in a hegemonic manner. Instead, if I am present, I am demanding of myself and it is in those spaces in which symbols start to appear.

Elena: When looking at your photographs, one can feel the cold of the mountain; it appeals to the senses through the body’s contact with nature. Many times, even if we do not know those landscapes, we are aware of them. Your work invites us to create and reformulate a new consciousness about the gaze in relation to the body and nature. Is this your objective?

Yes. When I stopped doing photojournalism I asked myself: How can photography recall smells, sounds, sensations and textures? The fact that there is an extra sensorial relation through a two-dimensional medium is very captivating.

Bruno Latour talks about the necessity of breaking our duality-based modernity, breaking identity as a systematic denial of the “other”. It appeals to the consideration of oneself as a node through which there is a circulation of knowledge, memories, objects and subjects, nature, etc. It seems that this proposal goes hand in hand with your photography.

That sounds amazing! Could you please share that information with me? However, my knowledge comes from my time in the Amazon and the Andes; observing and sharing with Mama Matilde in the mountains. She was my teacher, even for photography. That is how I learnt that things are not that binary, they are complementary.

ESPAÑOL

©Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira, Gathering Roots

Esta entrevista se hizo con la amable ayuda de Elena Gálvez Mancilla. Historiadora y socióloga mexicana, estudiosa de la Amazonia y la historia indígena, interesada por la imagen como fuente histórica, amante de la fotografía y activista ecologista.

No quiero dejar de mirar estas fotografías, nunca. Nada se queda quietx, sus movimientos ocupan mis sentidos. Cada imagen ocurre como si fuera una memoria lejana, previa a un exilio forzado de las montañas, el agua, la naturaleza y el conocimiento de vidas pasadas. Como si fueran de otro espacio y tiempo, pero aún así las siento sobre la piel.

Debo admitir que las fotos de Karen me llenan de felicidad; rememoran el juego, el descubrimiento, el cuidado y la consciencia. La posibilidad de coexistir con todas las especies se hace tangible cuando se es unx y lo mismo con la tierra. Todo lo que ha aprendido de lxs sabixs de los Andes y la Amazonía vive en estas fotografías. ¡Espero que lo disfruten!

Karen Miranda Rivadeneira es una artista Americana Ecuatoriana que se enfoca en la memoria, representación y la narrativa a través de procesos colaborativos e historias personales.

Karen ha colaborado extensamente con su familia para crear proyectos fotográficos y ha colaborado con diferentes comunidades indígenas en la provincia del Bolivar y Napo en Ecuador y mas recientemente en el desierto de nuevo mexico.

Ella ha exhibido en el Portrait Gallery el el Museo Smithsonian de Washington, DC, en el museo de Queens, Ella ha participado en el bienal de Musee Quai du Branly y recibio una beca de investigación del museo en el 2017. Ella ha participado en el New York Times portfolio reviews dos veces, en Fotofest en Houston, y en el tercer Latin American fórum en Sao Paulo, Brazil.

En el 2018 fue nominada para el Prix Pictec, el Foam Paul Huff Award, The Rolex Mentor & Protégé initiative y fue finalist del premio Hariban.

Publico su primer libro con Autograph ABP en 2018.

Karen es una de las mentoras para el Woman Photograph mentorship program y tiene el premio WeWomen en el cual esta desarrollando un proyecto en Nuevo Mexico.

Mi arte esta enraizada en la tierra que me formo y las historias que me cuenta.

Uso el cuerpo como espacio para narrar historias que rehusan ser categorizadas, y que crecen en la periferia, busco los territorios animísticos que están guardados en el abismo del pensamiento.

Pienso en el cuerpo como contenedor para la fuerza primaria mas creativa, pienso en la necesidad de soñar entre especies, y co crear con la tierra.

En la ferviente vehemencia que existe un legado de tradiciones en cada ser y que el ritual y el contar historias anima la memoria primordial que conecta a la célula y la persona.

Una memoria que hablaba una lengua común de mares, montañas y tierra negra, para luego ser transformado en cuerpos que migran.

Contemplando la tierra voy al pasado y futuro simultáneamente y

este acto de contemplación enciende al alma.

¿ Cómo empezaste a hacer fotografía? ¿Cuál fue tu proceso?

Empecé con pintura y performance y cuando terminé regresé a vivir a Ecuador. Estaba viviendo en Guayaquil y empecé a usar la cámara como un instrumento con el que podía capturar lo que veía, para entender el mundo.

Considero que mucha gente es creativa y artística pero no todos podemos pintar, dibujar y hacer escultura; entonces la relación con el arte se vuelve truncada porque no tenemos estas habilidades. En cambio, la cámara es un instrumento con el que todos podemos tener una conectividad con nuestro lado creativo.

Así comenzó, estaba en Guayaquil tomando fotos y de repente empecé a trabajar en El Comercio; no había ninguna mujer tomando fotos, eran todos hombres de 50 para arriba. En ese tiempo yo era un “bicho raro”; por ser mujer, joven, comparada con esos hombres mayores había mucha diferencia.

Después me interesó mucho ir a la Amazonía; viajar al oriente y conocer esa parte del país, que viviendo en la costa era un hemisferio muy lejano. Tenía 19 años y mi primer viaje fue sola y fue toda una aventura el simple hecho de llegar al lugar.

Finalmente, me dieron la oportunidad de viajar a Dinamarca por una beca para estudiar fotoperiodismo y eso me tomó un año. Fueron seis meses de estudio y los demás estuve viajando y fotografiando con la gente que conocí.

¿Quiénes son los artistas, o personas, que más influencia han tenido en tu trabajo?

El comienzo del gusto por la fotografía es un momento muy memorable. Si bien quizá no siga su misma línea de trabajo, el genio e ingenio de Graciela Iturbide fue de gran influencia. Es una de las primeras personas que admiré en cuanto a obra fotográfica. Otra fotógrafa importante es Adriana Lestido y todo el trabajo que hizo de mujeres, de hijas y madres, trabajos en la cárcel; son fenomenales. Esos trabajos me influenciaron, realmente me gusta la fotografía latinoamericana hecha por mujeres. Naturalmente, fue eso lo que me atrajo. De ahí, en el arte contemporáneo está Marina Abramović, sus obras me influenciaron mucho al comienzo. Ahora es mucho más difícil, me gusta tanta gente de distintas edades que no podría elegir.

¿Qué es lo que te inspira de América Latina?

Me gusta toda América Latina, todo, todo, todo. El respirar, los colores, la gente, hasta el roce con la gente en el bus para escuchar sus acentos; me pone muy nostálgica y me dan ganas de llorar al pensar en Latinoamérica. Cada vez que regreso a Ecuador desearía vivir ahí de nuevo. Pero también quiero ser muy franca, hay muchos problemas en Latinoamérica; hay mucha violencia, falta de equidad, etc. Sin embargo, creo que lo que me llama es el espíritu del sur de decir “todo está mal, pero seguimos adelante”. Me inspira mucho el espíritu de lucha.

Has desarrollado nuevas propuestas durante este tiempo de pandemia?

Estoy trabajando con video y performance, haciendo énfasis en aspectos geopolíticos y geopoéticos. Al no tener la oportunidad de viajar a Ecuador, he tratado de desarrollar desde un espacio personal. Tengo un lazo con el ecosistema y la naturaleza y quiero abordarlos sin entrar en diálogos indigenistas. A veces tendemos a la idea de que la respuesta está afuera, pero no hay que hacerlo como los demás, la respuesta está adentro.

Meda, tu última propuesta fotográfica, me parece interesante por el diálogo entre el cuerpo y la tierra. Me gustaría que nos cuentes cómo se desarrolló.

Meda trata sobre algo muy simple en realidad, trata sobre el cuerpo como la primera tierra y la tierra como el primer cuerpo; existe un diálogo entre ellos. También, en el proyecto, está una preocupación medioambiental y personal. Yo viví en Nuevo México, donde se puede ver el impacto del agua en la tierra. Gran parte del territorio es desierto, pero las formas muestran la memoria de que algo más existió allá, ahora el clima es muy distinto.

“Iyurina” es un término kichwa que significa: Entender el presente a través de la contemplación de la tierra. Mi interés recae en preguntarnos: ¿Qué estoy haciendo yo como ser humano por y para la tierra? ¿Qué influencia tienen mis acciones? Y sobre todo, la misma relación desde el otro lado. ¿Qué influencia tiene en mi la tierra?

Existe un proceso contemplativo y un análisis sobre la conectividad del cuerpo – la sabiduría que alberga al mantenerse así por 30.000 años. La obra investiga cómo activar nuestra sabiduría innata con la naturaleza. Al conversar con las personas que salen en mis fotografías, yo generaba preguntas como: ¿Cómo te relacionas con la tierra al imaginar que la estás tocando por primera vez? Así, cada una entró en su propia reflexión y su propio acercamiento a través del tacto y de sus cuerpos.

Meda no fue un título seleccionado por tener una etimología específica, es una palabra que me llegó. Cuando pienso en los títulos de los proyectos, me encuentro analizando la resignificación de las palabras a lo largo de la historia. Después, cuando investigué la etimología de Meda, una de las definiciones era ficticio. Cuando investigué la etimología de ficticio aprendí que significaba crear con arcilla, mover los dedos. Por ello, ficticio me pareció adecuado y así existe una resignificación de los términos que utilizamos.

©Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira, Spider-Woman

¿Qué significa rito y cómo lo podemos representar?

Es lo que estoy investigando ahora. Para mí el rito o ritual es como cambiamos el paradigma bajo el cual estamos viviendo. Porque ahora no existe tiempo para el silencio, para conectarnos con el agua y con la tierra, no existe tiempo para hacer eros – el placer de hacer algo que es para tí. Esos espacios no existen, y si existen, no se habla de ellos.

Las ideas sobre el rito, el descanso y nuestra relación con la tierra son muy antiguas; son innatas del ser humano y deberíamos rescatarlas.

¿Cuál es el rol de la espiritualidad en tu trabajo fotográfico?

La espiritualidad es el aroma que rodea mi obra. Quizás por la forma en la que he vivido y lo que he aprendido, se ha vuelto parte de cómo he aprendido a accionar.

©Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira, She Sees Seashells

Elena: Lo que dices me ha recordado mucho a comunidades indígenas Mayas, de donde yo vengo, en México; ellos dicen que el pasado nunca está atrás, sino que está en frente. Se toma en cuenta el regresar a una sabiduría presente, que regresa, muchas veces de forma inconsciente. Veo eso en tu trabajo fotográfico. También encuentro una ruptura de la misión histórica de la fotografía – la documentación de lo verdadero. Existe todo un reservorio de simbología en tus imágenes; la mujer, el territorio. Son fotografías de cosas muy específicas, que a la vez hablan de algo muy universal. ¿Cómo eliges esos símbolos y sitios?

Los elijo al pensar que la experiencia me enseña algo de la vida que es absolutamente escencial. Parte del trabajo fotográfico es cocrear con el universo. Nunca me ha servido trabajar a través de la imposición, de forma hegemónica. En cambio, si estoy presente, demando todo de mí y en esos espacios los símbolos empiezan a aparecer.

Elena: Al mirar tus fotografías, se siente el frío de la montaña; apela a los sentidos con el contacto del cuerpo con la naturaleza. Muchas veces, aunque no conocemos los paisajes que muestras, los tenemos presentes, en algún imaginario. Tu fotografía parece invitarnos a crear y reformular una nueva consciencia de la mirada sobre la relación entre el cuerpo y la naturaleza. ¿Es este tu objetivo?

Sí. Cuando dejé de hacer fotoperiodismo me hice una pregunta: ¿Cómo ver a la fotografía como algo que nos pueda recordar olores, sonidos, sensaciones y texturas? Sobre la fotografía, me ha cautivado mucho la relación extrasensorial que trato de crear a través de un medio de dos dimensiones. Como tratar de hacer al calor, frío.

Bruno Latour habla de la necesidad de romper la modernidad que se basa en la dualidad. La identidad como negación sistemática de lo otro. Apela a considerarnos nodos por los que circulan conocimientos, memorias, objetos y sujetos, naturaleza, etc. Me parece que esta propuesta va muy de la mano con tu fotografía.

Me parece increíble, por favor, envíame esa información. Sin embargo, mis conocimientos vienen de mi tiempo en la Amazonía y en los Andes; de compartir y observar con la Mama Matilde en las montañas. Ella fue mi maestra para aprender fotografía. Así aprendí que las cosas no son tan binarias, sino complementarias.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026