Wrongful Convictions: Interview with Jason Kerzinski

When Jason Kerzinski started interviewing public defenders in New Orleans, he never imagined it would be a new beginning in his artistic career. Kerzinski, a New Orleans based street photographer and photojournalist, was inspired by his conversations with the attorneys to tell a larger story: wrongful convictions. From there he connected with the Innocence Project New Orleans, an organization dedicated to freeing people “sentenced to life in prison and those serving unjust sentences.”

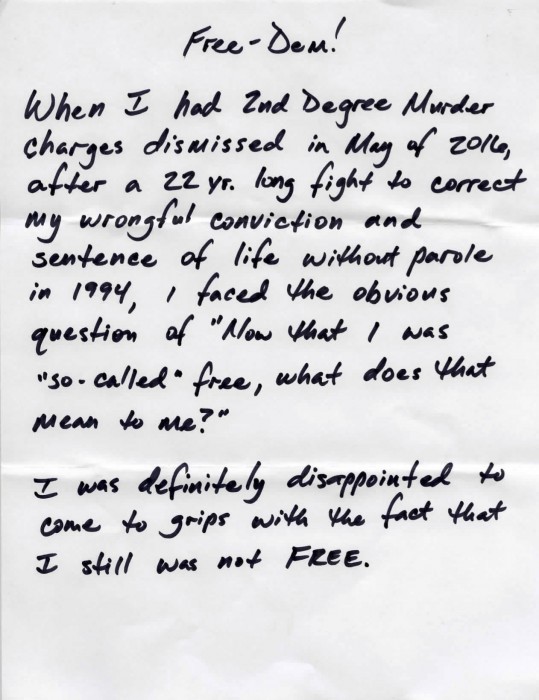

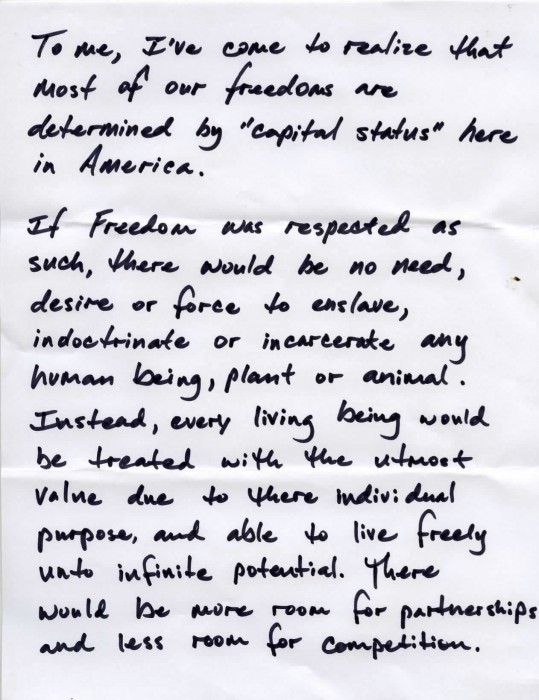

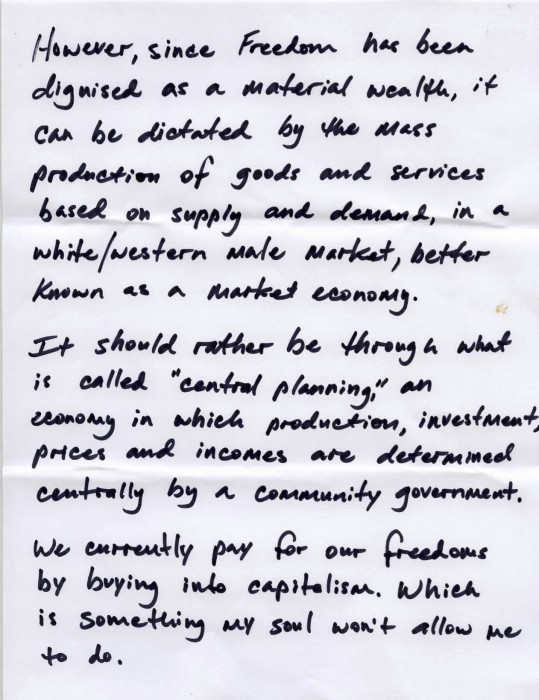

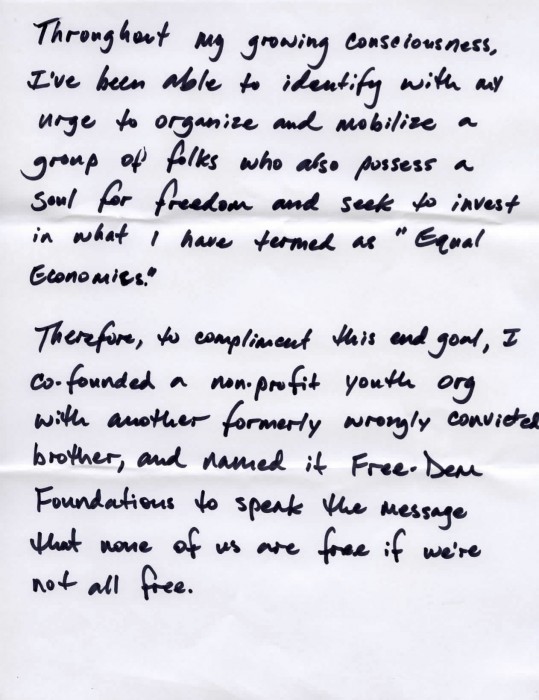

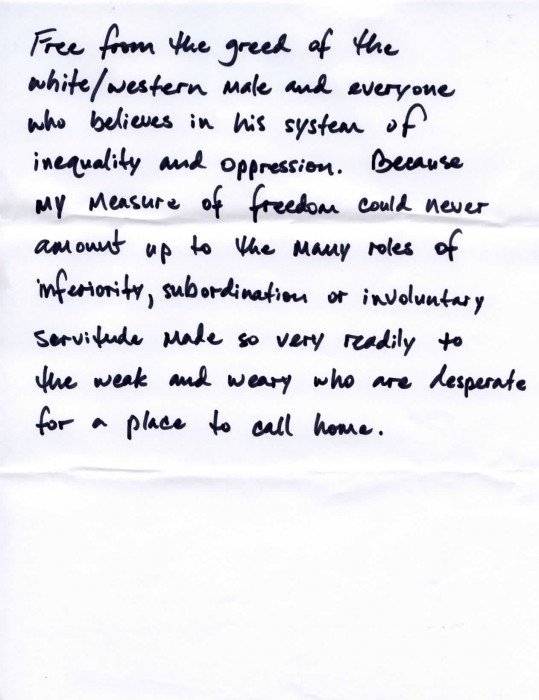

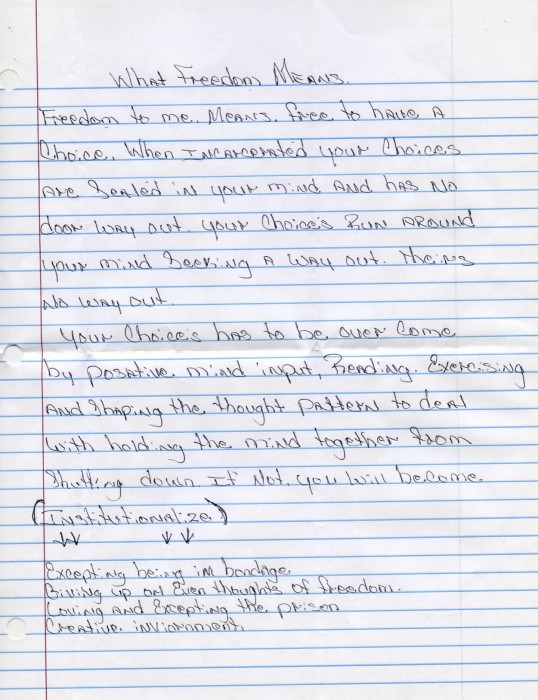

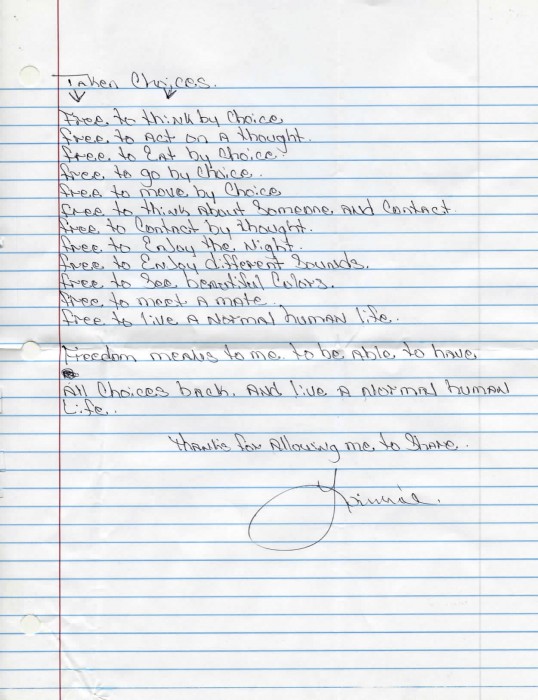

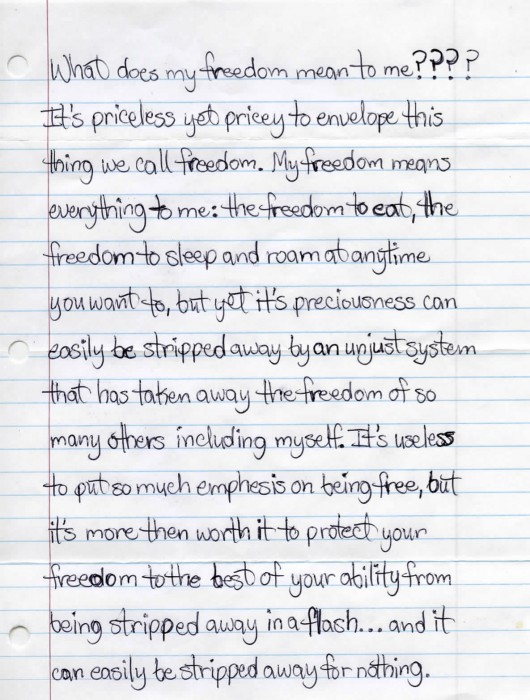

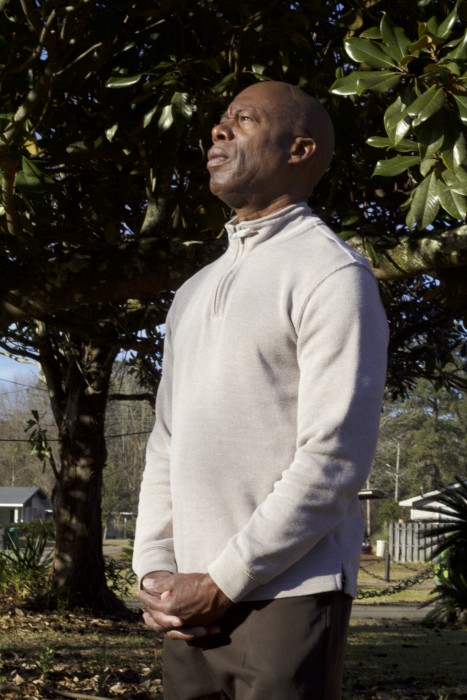

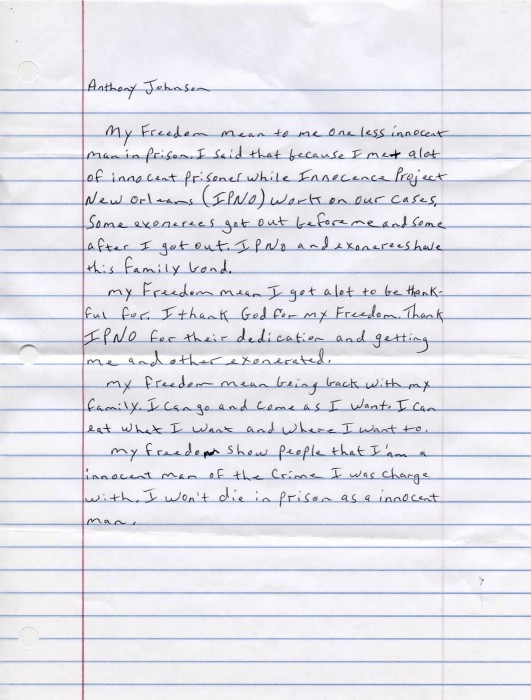

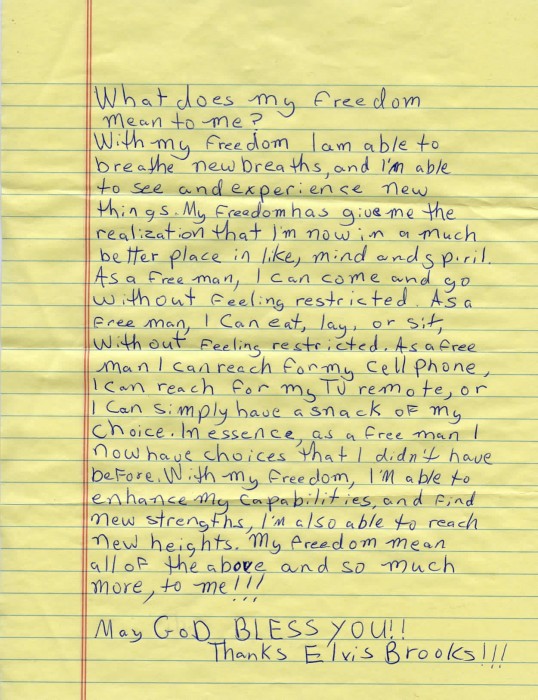

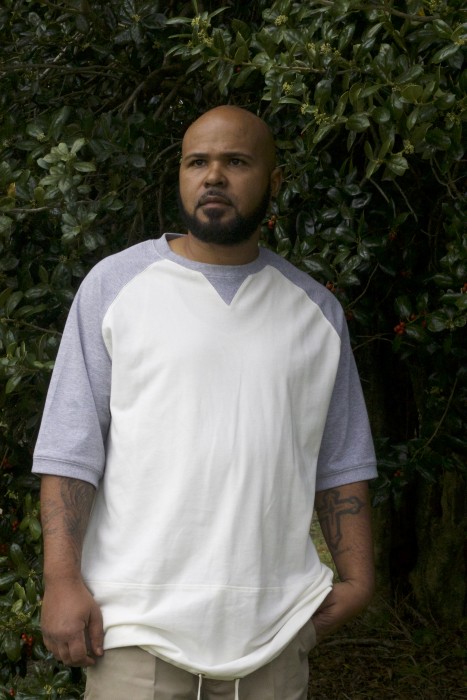

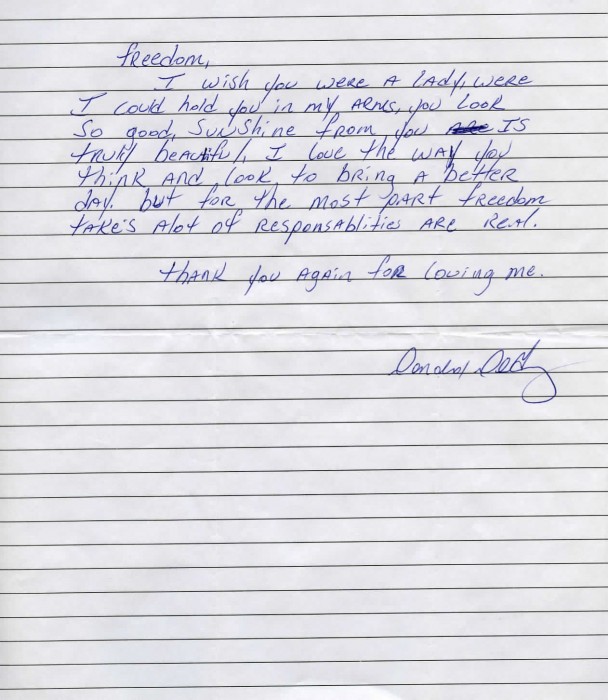

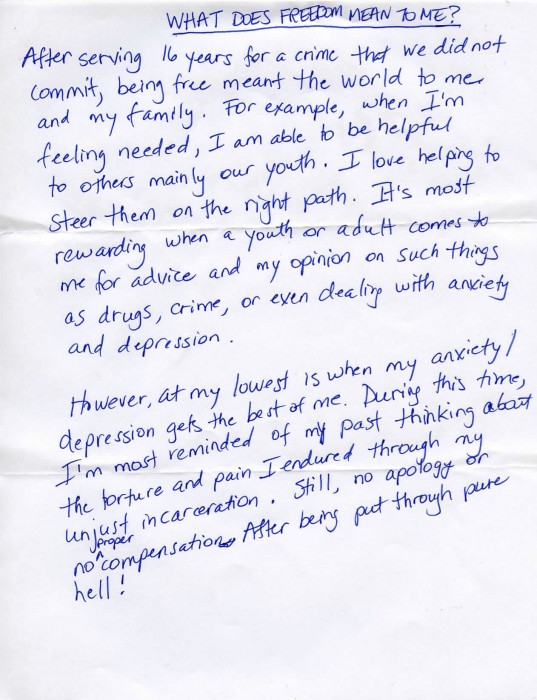

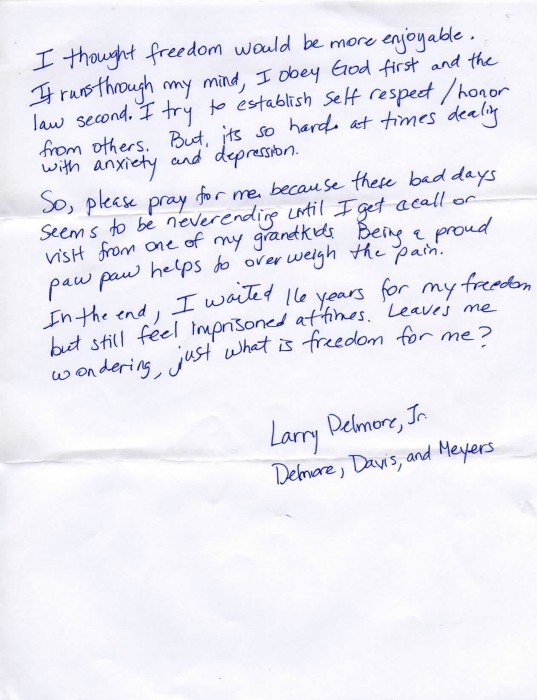

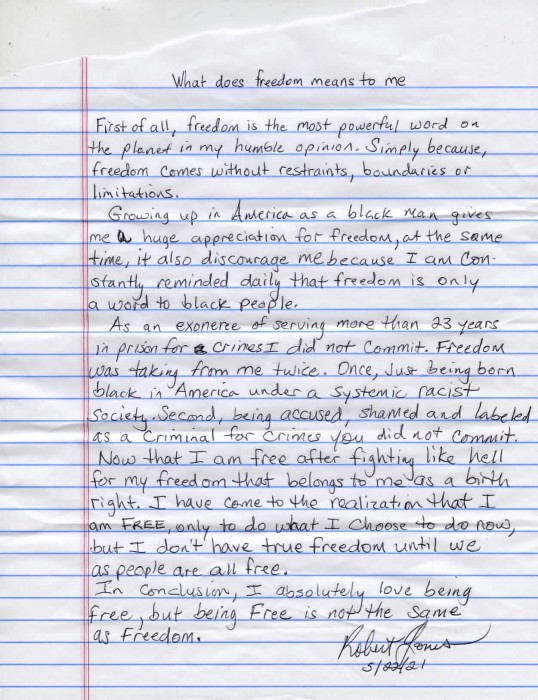

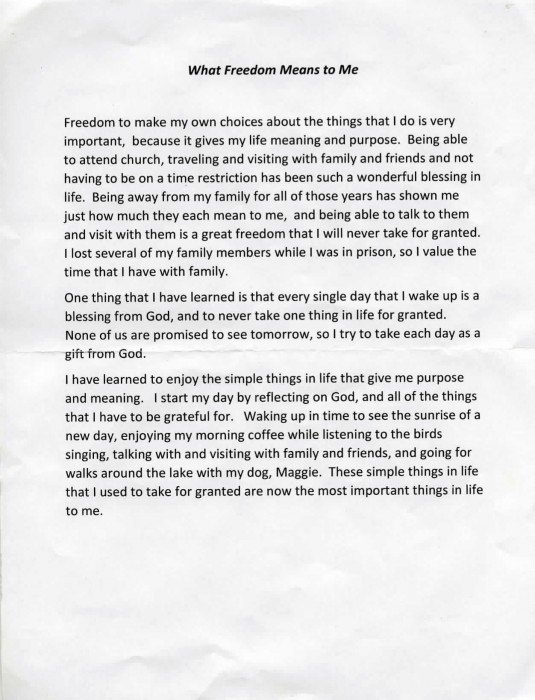

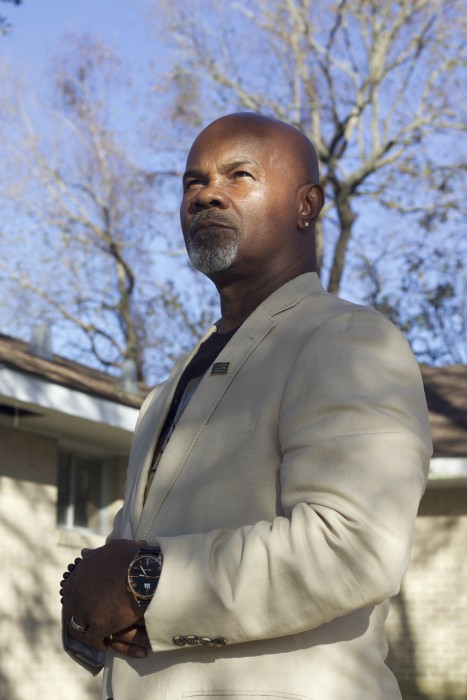

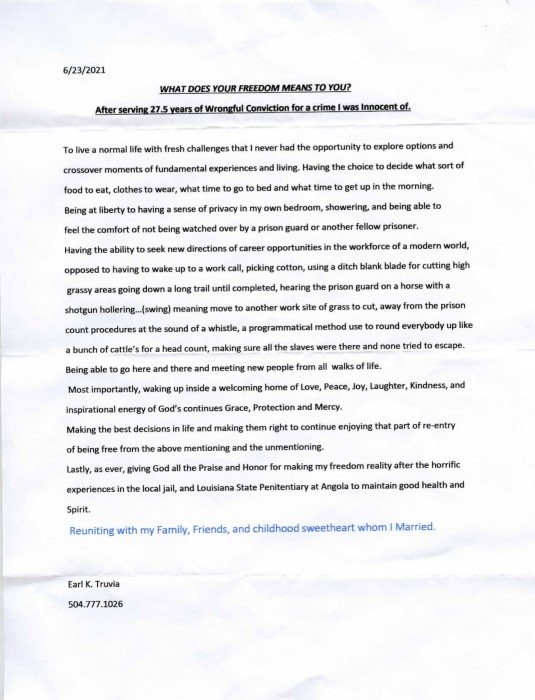

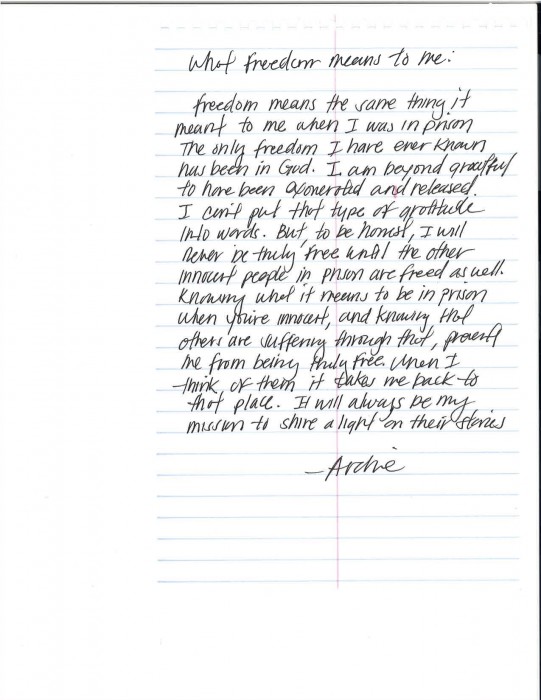

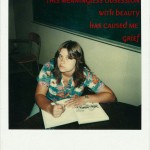

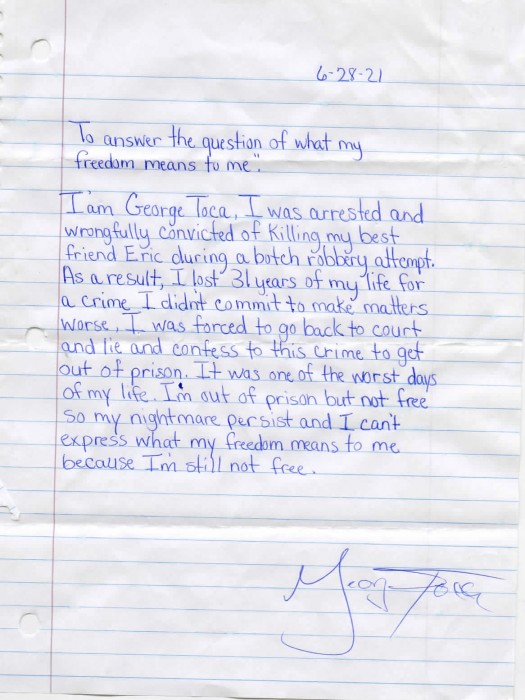

The result is his project, Wrongful Convictions. Kerzinski took portraits of recently exonerated individuals and asked them to write down their response to the question “What does freedom mean to you?” The result is somber, yet hopeful. The subjects stand victorious in their portraits, their faces turned to the sun, taking in the world around them. Their letters are joyous but tinged with the reminder of what was taken for them. Paired together the images and writings are living evidence of a broken criminal justice system. A reminder of the systemic inequity that led them to be wrongfully convicted, and the power of the community that freed them. Now they stand out in the world, ready to live the life that they deserve.

Below is a conversation with Kerzinski about his artistic process, his start as a photographer, and what he took away from this project. You can find him on Instagram at @504living.

“I decided to pick up the camera because of my circle of friends who are photographers. I ended up purchasing a Pentax K1000 on eBay and I began to watch YouTube videos obsessively on how to operate the camera. From there, I began to make photography part of my daily practice. The camera is a tool that I use to engage with the people who live in New Orleans.The photographs I take are a documentation of the encounter between the subject and myself. I spend time getting to know the people I capture, and I hope they feel as if they’ve gotten to know me, too. In relationship, and in the work itself, this is an effort to dispel the myths of New Orleans—and surrounding areas—by focusing on its people. I hope to give everyday people a platform and connection to a larger audience.”

Wrongful Convictions

This particular project began after a series of interviews I conducted with public defender’s in New Orleans. Before the interview, I had asked each attorney what they thought needed to be talked about, what needed to change. I wanted to have a discussion with attorneys beforehand, so I had an opportunity to do some homework in preparation for the interview. The purpose of those interviews was to give them a platform to speak about the inner workings of the criminal justice system, that way the public had a better understanding of the legal system. After that project concluded, I wanted to learn about wrongful convictions, so I got in touch with the communications director at Innocence Project New Orleans (IPNO), and the project was underway. My goal from the outset was to highlight the voices of those who went through that lived experience by asking a thoughtful question that would elicit a wide range of responses. With the help of Jimmy Bass, one of the exonerees, I settled on this question, “What does your freedom mean to you. “

Elizabeth Wayne: How did you get started in photography? You say that you are self-taught, tell me what drew you to the art form?

Jason Kerzinski: I started out as a painter, painting with shoe polish and acrylic large-scale portraits based on photos of the deceased that I found while reading obituaries in the Chicago Sun-Times. These paintings were central to my recovery as an alcoholic. The obits gave me a sense of belonging. I was missing human connection in my life. I had felt dormant for so long, and it was as if the portraits I painted were bringing me back to life. Painting gave me a sense of purpose and structure missing in my life. Those paintings were the stepping stones to becoming a photographer. It wasn’t until I reached my thirties that I began to explore photography. When starting out as a photographer, I was on the lookout for elusive moments. To become a photographer, I thought I had to capture images the way that Henri Cartier-Bresson had done—he was one of the few photographers whose work I was aware of at the time. Cartier-Bresson’s work led me to believe that I had to snap a photo as a moment was unfolding, like that famous reflection image he took of the man jumping over a puddle. As much as I tried, I felt these moments were eluding me and I was chasing phantoms. From my photographer friends, I learned that the art of photography includes a vast array of approaches and methods. I asked myself what I could express that came from inside, and realized that I wanted to go deeper, to speak to people, to feel connected to those around me, to become a storyteller. I use the camera as a way to connect with the community around me. I feel like I’m making genuine connections.

EW: What is your process when it comes to street photography? What about New Orleans makes it a good place for storytelling?

JK: New Orleans is a great place for storytelling because everyone has a story—no exaggeration. Twelve years ago, when I arrived in New Orleans from Chicago, I met people who launched into their life stories soon after we exchanged a “hello.” These people had an openness that I’d never experienced before. Connecting with New Orleanians made me feel like I belonged to the city. When I started to study portrait photographers, such as Diane Arbus and Dorthea Lange, I knew I wanted portraiture as my focus. As for my process, I like to walk or bike around New Orleans with my camera and just interact with my surroundings. My practice is very nonchalant. I don’t really have a method when I’m out in the streets.

EW: You first started this project after conversations with public defenders regarding the modern legal system and prisons. How did you become interested in telling stories about the carceral system in the United States?

JK: My interest in the carceral system goes back to my twenties, when I had dealings with the legal system. Up close, I saw the theater of the courts. If you could afford an attorney, you could count on a slap on the wrist. I felt uncomfortable or unnerved by what went on in the courtroom, seeing my lawyer chummy with the prosecutors and judge, while families sat in silence waiting for their loved ones’ cases to be called. As a young white kid, even without much money, the system was designed to help me and disadvantage everyone else. It wasn’t until my thirties that I began to process what had happened to me a decade earlier. The justice system seemed like a sham, but I only understood the bare outlines of the racism and injustice that went on—so I took it upon myself to learn more. A friend who worked as an investigator for the Orleans Public Defender’s Office put me in contact with a public defender he knew named Alexis Chernow. When I spoke with her in the summer of 2018, we discussed “Breaking Brady”—a common practice in New Orleans where prosecutors withhold evidence from the defense. Later that summer, we collaborated on an interview that explored prosecutorial misconduct. That interview led me to conduct four additional interviews with attorneys on staff at the Orleans Public Defenders Office, where I made a deep dive into the legal system that led me to recognize patterns of ongoing and pervasive injustice.

EW: What was it like working with Innocence Project New Orleans?

JK: I had a great experience with Innocence Project New Orleans. Cat Forrester, the communications director, went above and beyond to help me get this project up on its feet. I’m grateful for her support and hard work.

EW: Describe your method for taking these portraits. I imagine it is an emotional process for both you and the subjects, do you think that comes across in this body of work?

JK: The portraits are emotional for myself as the photographer as well as the subjects of the photographs. My relationships with the exonerees started over the phone with conversations every week, allowing us to cultivate trust. At first, I doubted that I had the journalistic chops to complete the project. When the pandemic started in 2020, the weekly phone calls offered emotional stability during an unstable time in our country. As everything felt as if it were falling apart, these conversations were a lifeline. My process was to engage with the exonerees as I’d done with the New Orleanians I’d met while on my photo walks. Those outings in the streets had prepared me for this project. The portraits of the exonerees reflect the rapport I established with them.

EW: How do the written responses to the question, “What does freedom mean to you” work in tandem with the portraits?

JK: The question “What does freedom mean to you?” humanizes the topic of wrongful conviction and makes it more real—and less of an abstraction—to the viewer. With the media cycle moving at warp speed, few people find time to delve into long-form articles about social justice or civil rights. The exonerees’ portraits and their answers to the question condenses a complex issue into a form that is both enlightening and uplifting—allowing the audience to view the world through a more compassionate lens. Writers such as Studs Terkel who interviewed working-class people have inspired me to pursue this type of grassroots storytelling. Identifying with each other’s experiences, trials, and triumphs is what binds us together as a people.

EW: The subjects in this series have fascinating yet frustrating backstories and years of their lives have been taken away by a corrupt legal system. What did you learn from your conversations with them?

JK: From the exonerees, I learned to lead with my heart. I learned that I needed to remain in touch with my humility. Despite the years they lost to incarceration, they have found a way to keep going. I learned that things may seem insurmountable or imbalanced but sometimes wrongs are made right—even if much too late. Before meeting these men, I was far more pessimistic. But their positive outlook, their ability to survive, their capacity for forgiveness, and their strength to move forward have changed the way I look at life.

This story was originally published by Scalawag, a journalism and storytelling organization that illuminates dissent, unsettles dominant narratives, pursues justice and liberation, and stands in solidarity with marginalized people and communities in the South.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Ian van Coller: Naturalists of the Long NowApril 22nd, 2024

-

Amy Lovera in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 23rd, 2024

-

Brittany Marcoux in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 22nd, 2024

-

Penumbra / Image Threads LTP: Adam Meeks and Raymond Meeks in ConversationSeptember 9th, 2023

-

Penumbra Foundation / Image Threads LTP: Again and Again: Ruth Lauer-Manenti and Evan Davis in ConversationSeptember 7th, 2023

George Toca letter, ©Jason Kerzinski, from Wrongful Convictions

George Toca letter, ©Jason Kerzinski, from Wrongful Convictions