The Dynamics of Photography and Disability: Mari Katayama: Bystander

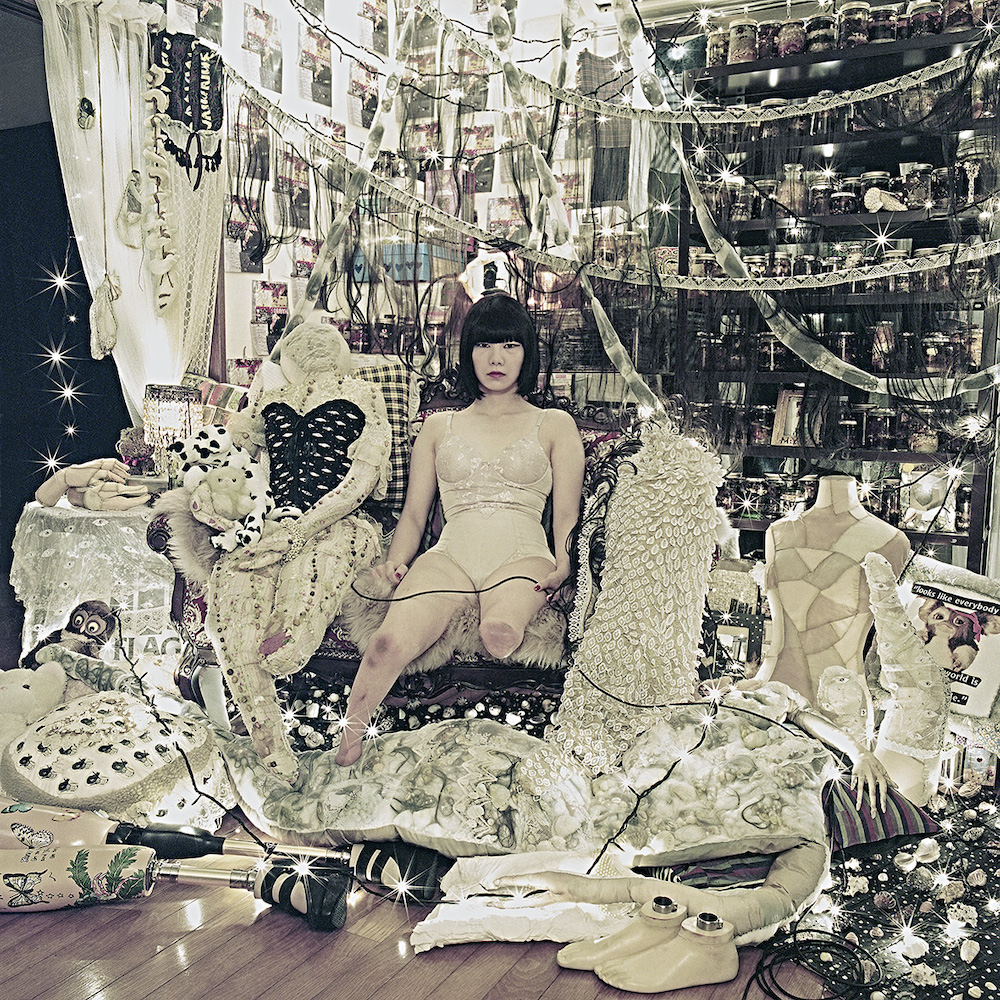

©Mari Katayama, Shell, 2016 Image description: Mari gazes directly at the camera and is holding a shutter release cord. She is lit by twinkle lights and surrounded by personal artifacts. She is wearing a cream corset, has a bob haircut, and is reclining in a loveseat. Beside her sits a lifesize doll, a handsewn replica of herself – and on the floor in front, decorated with images of leaves and butterflies, lie her prosthetic legs, each shoe adorned with twinkle lights. The mirror in the middle shows a camera. It signifies the “eternity” that exists in the mirror.

This week we are looking at projects by disabled/chronically ill photographers. The definition of dynamics is “forces or properties which stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.” Each of these artists is approaching their work in ways that embrace this meaning, enacting change and raising important questions about societal systems through their ideas, craft, and processes they use.

Born 1987 in Saitama and raised in Gunma, Japan, Mari Katayama graduated with a Master’s degree from the Department of Intermedia Art at Tokyo University of the Arts in 2012. Suffering from congenital tibial hemimelia, Katayama had both her legs amputated at the age of nine. Since then, she has created numerous self-portraits, alongside embroidered objects and decorated prostheses, using her own body as a living sculpture. Her belief is that tracing her own self connects her with other people, and that just like a patchwork is made by stitching together edges with needle and thread, her everyday life can also be connected with wider society and the world.

In addition to her creative art, she has also worked as fashion model, singer and keynote speaker at international events. She also leads the “High Heels Project”, which has recently entered its second phase. The motto of the project is to use the body and art in any way possible to achieve “freedom of choice.”

Her major exhibitions include, “home again” (Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, France, 2021), “58th Venice Biennale 2019” (Giardini and Arsenale, Venice, Italy), “broken heart” (White Rainbow, London, 2019), “Photographs of Innocence and of Experience – Contemporary Japanese Photography Vol.14” (Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Tokyo, 2017), “on the way home” (The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma, 2017), “Roppongi Crossing – My Body, Your Voice” (Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2016), “Aichi Triennale 2013” (Nayabashi, Aichi), etc. Public collections include La Maison Rouge (Paris, France), Collection Antoine de Galbert (Paris, France), Mori Art Museum (Tokyo, Japan), Arts Maebashi (Gunma, Japan) and Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (Tokyo, Japan). She received the Encouraging Prize of Gunma Biennale for Young Artists in 2005, Grand Prix of Art Award Tokyo Marunouchi in 2012, Higashikawa Award for The New Photographer category in 2019 and Kimura Ihei Award in 2020. Her major publications include “GIFT” (United Vagabonds, 2019).

Statement

I always liked going out. As a child, I often begged my grandmother for a piggyback ride and she took me for a walk in the neighborhood. Concerned about my feet being exposed, she firmly held them in her hands. I felt deeply touched by her kindness, almost to the point of sadness, but I loved the feeling of holding on to my grandmother’s back, resting my feet in her palms.

In 2015, I traveled to Ashio several times while searching for a house in Gunma. The Watarase River runs through the region where my grandfather lives. The upstream and downstream areas of the river, surrounding mountains and fields, as well as the people living there, suffered from severe water and soil pollution due to the Ashio Copper Mine Mineral Pollution Incident—Japan’s first pollution case in the late 19th century. Due to mine development and toxic substances from the factory smelters, mountains near Ashio town became barren and river fish died, while field harvests dropped drastically. Death and stillbirths occurred from mineral poison and economic hardship from poor harvests amounted to more than 1,000 people. The smelter continued to operate until the 1980s and is now recorded in our textbooks as “history”. The mountain was about an hour drive from my house, and the river has always been in the scenery of my life.

Enormous factories, congregate apartment blocks, steel towers, electric substations, guardrails, banks, and the river—reflecting on how most of them are artificially made and maintained generated a lot of hope in my heart. I had no doubt that the same applies to my body, which had undergone surgery—just like my poor scribbles or sewing and many other little things that don’t have a name. Humans can create anything! And can do anything!

But instead, I found my notebooks and textbooks torn to shreds in school, and my seat was taken from the classroom. In town, a shower of sympathetic words poured over me, people saying, “poor you”. The television disseminated news of brutal realities and wars erupting all the time around the world. Humans can also destroy any building no matter how big—and even our minds that have no shape or form.

Ashio reminded me of this—history, abandoned factories that still remain there, houses for the local people, and the river that leads to my hometown. Are these all a thing of the past?

After renting a small apartment, I immersed myself in making art every day.

My hands are hard workers. They work also as my two feet that were amputated when I was nine years old. Hand-crafted work that I’ve been accustomed to since I was a child has taken me outside and into the world—that’s also what my hands have accomplished.

I believe that beauty is inside everyone, and can be seen and felt as beautiful by everyone, no matter what. Beauty, unlike art, is certainly not for those privileged.

In the making of objects and self-portraits, tracing my own outline was equal to pursuing the beauty that everyone contained. It was one thing I truly desired since my childhood; that no matter how hated I was, I may too have such beauty.

The needles and threads that pursued this beauty connected the boundaries between family, neighbors, life, and society. I learned that I have within myself the same as you do. I am you. I think it’s the most intimate eternity one can feel.

©Mari Katayama, Bystander 08, 2016 Image description: Mari is laying on a bed and looking at something off to the side. She is hugging a soft fabric pillow-like multi-armed sewn sculpture.

Megan Bent: Please tell us a bit about yourself.

MK: My name is Mari Katayama. I make hand-sewn objects, photographic works such as self-portraits, and installation works. I currently live with my daughter and husband in a rural town in Japan.

MB: How did you get into photography? What compels you about the photographic medium?

MK: I have been familiar with the single-use camera and Polaroid since I was a child. My grandfather was a photography lover.

The main reason I chose photography as my artwork was when I was a teenager, when social networking services were not yet as popular as they are now, I was registering on MySpace and programming HTML to create my own homepage. I was sewing with a needle and thread before I was taking pictures or holding a pencil. But I couldn’t make anything concrete and useful (clothes, bags, or anything that had a clear use), so I started making things like “objects” at that time. I needed a photo to put it on my website. But I didn’t know what it would look like if I put it on the website exactly as it was. I began taking “self-portraits” of myself as a mannequin to illustrate the objects.

MB: How would you describe your art practice?

MK: Hmmm…like life, I guess. Production and life are inseparable.

Thinking about production is like asking, “Why do you make a living?” “Why are you alive?” It is similar to being asked the question, “What is the best way to get a good result?”

Since I am a contemporary artist, I am re-premised to live in the contemporary world.

©Mari Katayama, Shadow Puppet 001, 2016 Image description: A black and white photograph of Mari. She is in silhouette and is bringing her two fingers up to touch her lips. She is next to a shelf containing many glass jars.

MB: You have described your practice of making as a form of communication when words weren’t enough. Could you say more about that? And how has that process of making/communicating transformed over the years?

MK: I have much to learn in raising my daughter, who will be five this year.

She inputs everything I and my husband do around her. And then she outputs them as they are.

Therefore, we cannot lie to her, nor can we make things up. I think therein lies the essence of expressive activity (i.e., artistic activity).

MB: What does disability mean to you?

MK: Disability is something that people create.

Disability is something that can be defined by people or outlined by society.

For better or worse, I could not have discovered my disability without getting involved with others.

©Mari Katayama, Bystander 001, 2016 Image description: Mari is lying on a wooden floor wearing a white slip dress, red lipstick, and a soft, fabric, multi-armed sewn sculpture. She is looking up at the camera.

MB: What does the process of sewing mean for you?

MK: This is also the most basic and most important thing in my life, something I can confidently say I am good at. I think it is very important to have what you are most confident in.

MB: Is there a specific image you have made that taught you something new?

MK: It always does. When I am creating, the work is making me create. So sometimes I don’t even know what I am doing. And after it is completed, sometimes I know right away, and sometimes I am taught after several years. Sometimes I receive a different message each time I encounter it.

I realize that a person’s life is at most 100 years, but the time frame of a work of art is different from that.

©Mari Katayama, Beast, 2016 Image description: Mari reclines on a loveseat and is partially covered by a cream blanket. Beside her sits a lifesize doll, a handsewn replica of herself – she is surrounded by twinkle lights, personal artifacts, and on the floor in front, decorated with images of leaves and butterflies, are her prosthetic legs. Each shoe adorned with twinkle lights. The mirror in the middle shows a camera. It signifies the “eternity” that exists in the mirror.

MB: Do you feel there is a performative aspect to your work? Do you consider your work self-portraiture?

MK: I was a mannequin in my early self-portraits. Therefore, I was not really aware that the beings in the photographs were myself. However, in my recent works, I feel that I am photographing and expressing my body in a more straightforward approach. I think they are self-portraits. In that sense, I feel that there is a performative aspect to the work. I think these changes are influenced by what I just answered:

I have much to learn in raising my daughter, who will be five this year.

She inputs everything I and my husband do around her.

And then she outputs them as they are.

Therefore, we cannot lie to her, nor can we make things up.

I think therein lies the essence of expressive activity (i.e., artistic activity).

MB: Which other photographers/artists have influenced you?

MK: Painters Kazuki Yasuo, Modigliani, and Marcel Duchamp, I think.

I have been reading their books and collections of their works since I was a child.

©Mari Katayama, Bystander 004, 2016 Image description: Four hands reach and touch the fabric of Mari’s sewn fabric sculpture made of replicas of the hands of the puppeteer on the island of Naoshima. Some parts of the sculpture are filled with shells and beach ephemera.

©Mari Katayama, Bystander 014, 2016 Image description: Mari reclines on a beach with her head resting on one arm. She is gazing into the camera and is wearing a soft, fabric, multi-armed sewn sculpture representing the many hands and arms of the puppeteers on the island of Naoshima.

MB: In your bystander series, you collaborated with many people from the island Naoshima, photographing, printing, and sewing fabric hands of Naoshima Onna Bunraku puppeteers. This makes me think about interconnectedness/interdependence. What did the process of collaboration bring up for you?

MK: When I was invited to do research, make art, and hold a solo exhibition in Naoshima, I was very worried about what I could do. At that time, I did not yet have a studio and was making objects and taking photographs in my room, so I felt like I was under a lot of pressure to go out and relate to other people.

So I thought to myself, “First of all, I should make friends with the people of Naoshima. Let’s not worry about the production of the work. If I want to do it, I can do it” (laughs).

Print the photos on cloth and make objects out of the cloth. Wearing the object, I take self-portraits. This has been my way of working since before Naoshima.

It was a new experience for me to have others participate in this process, and as a result, I was able to do something I had never imagined and had the courage to go out and engage with others.

©Mari Katayama, On the way home 001, 2016 Image description: Mari is standing on a bridge. She is wearing her prosthetic legs and is holding a soft, fabric sewn sculpture that covers most of her body. She is looking off into the distance and a shadow of her body and sculpture is cast onto the pavement in front of her.

©Mari Katayama, On the way home, installation detail, 2017 Image description: A detail of the on the way home exhibition. In the center of the gallery hanging from the ceiling is a net. Appendage like, cream, see through fabric hangs down from the net and is filled with beads, shells, and other organic ephemera. On the wall in the background are framed photographs.

MB: Looking at the installation photographs from your exhibition 帰途 on the way home at the Museum of Modern Art Gunma there are so many things that captivate and move me. I love the net which is cast above the gallery. There is delicate appendage like drops of mesh descending from it filled with beads, shells, and other organic ephemera. Can you share more about this decision and other decisions you made in this exhibition space?

MK: This place is a museum in my hometown that I have often visited since I was a child.

I was very poor as a child, and I often went to see the exhibitions of the museum’s collection.

I think the exhibition was inspired by the idea of “coming back there” or “circulation”.

That is how I came up with the title of the exhibition, ”on the way home”.

Life seems to be a cycle of repetition. Of course, they are not exactly the same each time, but they come and go with different forms and meanings. And each time we repeat them, something different is born even if we are doing the same thing.

Even mountains that seem natural at first glance are planted with trees and have been touched by human hands. And if we look around at our lives, everything is made by human hands. Guardrails, food, clothes, artwork. So since I was a child, I would look at those things and think, “Humans can do anything!” I have lived my life with hope. Of course, humans are capable of destroying the environment and hurting people. We can do “anything,” including those things.

Computers, desks, floors, glass. Planted trees and artificially altered figures by cosmetics and surgery. Things that look “unnatural” at first glance shine beautifully when there is “life” in them.

With this in mind, I spent my childhood in my hometown, a rural town in the middle of nowhere.

Because I find the beauty of artificial things as beautiful as the beauty of things born in nature.

I use shells and pearls as symbols of them. Our idea of “nature,” and the “beauty” and “rightness” that are so often associated with it, are also constant themes in my creative work.

What exactly is our idea of nature, beauty, and rightness?

©Mari Katayama, On the way home, Installation detail, 2017 Image description: A detail of the on the way home exhibition. On a pedestal is the soft, fabric, multi-armed sewn sculpture. In soft focus in the background are photographs on the wall and a net hanging from the ceiling.

©Mari Katayama, You’re mine, 2014 Image description: Mari reclines on a white bed and an assortment of white pillows. She is wearing a cream corset, has her hair in a bob, red lipstick and fingernails and grey stockings covering her legs.

MB: What are you working on now? Is there anything new and upcoming you would like to share?

MK: I am preparing new works for a solo exhibition to be held in Japan in the summer. I also want to make video work. This year, I will resume the “High Heel Project”, an activity I started in 2011 in which I sing songs while wearing high heels with both prosthetic legs. This project is based on the theme of “the freedom to choose whether one wants to do it or not,” regardless of whether one has a disability or not. In other words, I will resume my musical activities as well!

Megan Bent is a lens-based artist interested in the malleability of photography and the ways image-making can happen beyond using a traditional camera. This interest started to occur after the diagnosis of a progressive chronic illness. Drawn to image-making processes that reject perfection, accuracy, or any certainty in results, she is interested instead in processes that reflect and embrace her disabled experience; especially interdependence, impermanence, care, and slowness

Her artwork has been exhibited nationally at The Halide Project in Philadelphia, PA, The Center For Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO; The East Hawaiian Cultural Center/HMOCA in Hilo, Hawai’i; Flux Factory in Long Island City, NY; El Museo Cultural, Santa Fe, NM; The Foster Gallery, in Dedham MA; Soho Photo Gallery in Tribeca, NY; the Austin Central Library Main Gallery in Austin, TX, and internationally at F1963 in Busan, South Korea; Alternative Space 298, Pohang, South Korea; and Fotosotrum in Barcelona, Spain.

She is currently an artist in residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency and has been an artist in residence at the Nobles School in Dedham, MA, and the Honolulu Museum of Art, HI. She has presented her work at Atlas Obscura: The Secret Arts, The Pacific Rim International Conference on Disability and Diversity in Honolulu, HI, at Other Bodies: (Self) Representation, Disability and the Media at the University of Westminster in London, U.K., and at Critical Junctures at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Her work has been featured in Analog Forever Magazine, Fraction Magazine, Too Tired Project, Rfotofolio, and Float Photography Magazine.

Follow Megan Bent on Instagram: @m_e_g_g_i_e_b

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024