Kim Beil in Conversation with Klea McKenna

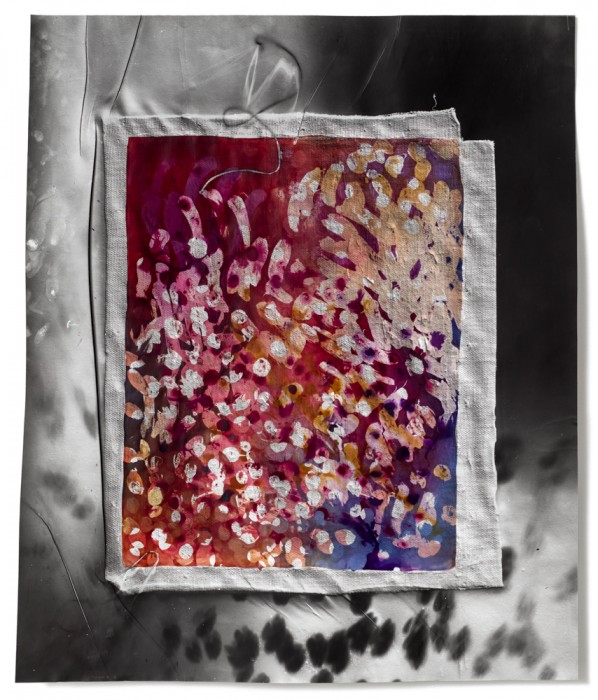

©Klea McKenna, Rainbow Bruise 13, Photographic relief (embossed gelatin silver photogram, fabric dye), 23×19”, 2021

When I met Klea McKenna at her studio this winter, she had to push aside a pile of colorful vintage handkerchiefs to make space for me to sit. Whether embroidered, lacy, colorful or plain white, these square pieces of fabric were once the canvases of their owners’ lives. Handkerchiefs were with people in sickness and in health, or proffered to friends and loved ones in times of need. Stuck at home during the early months of the Covid-19 McKenna began using the handkerchiefs to make photograms. Exposing them to sunlight, a shadow image appeared slowly over a period of days. The incremental changes in light-sensitive dye, like the slow blur of time many people experienced in the spring of 2020, becomes the image. McKenna’s images traced the outline of these new times and layered them in correspondence with the past.

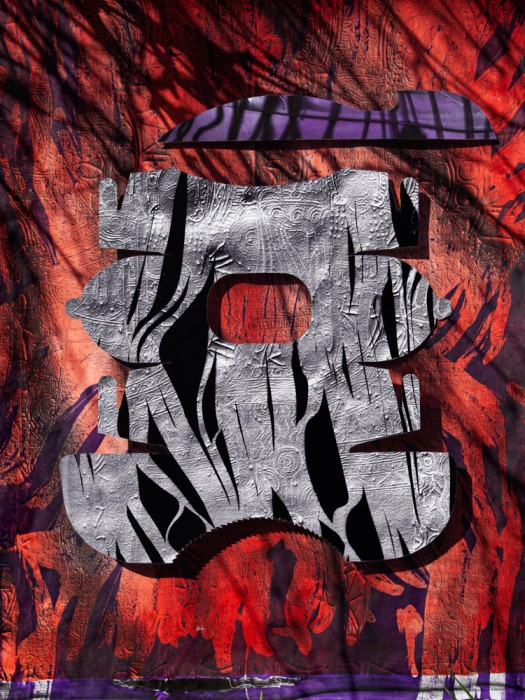

McKenna’s most recent body of work, Rainbow Bruise, on view until August 11 at Euqinom Gallery in San Francisco, likewise draws inspiration from historical objects: paintings McKenna found at flea markets, garage sales, and on eBay. In this conversation, we discuss how McKenna’s attraction to the past has animated her work, as well as her talent for remixing familiar media to make new hybrid forms that are always greater than the sum of their parts.

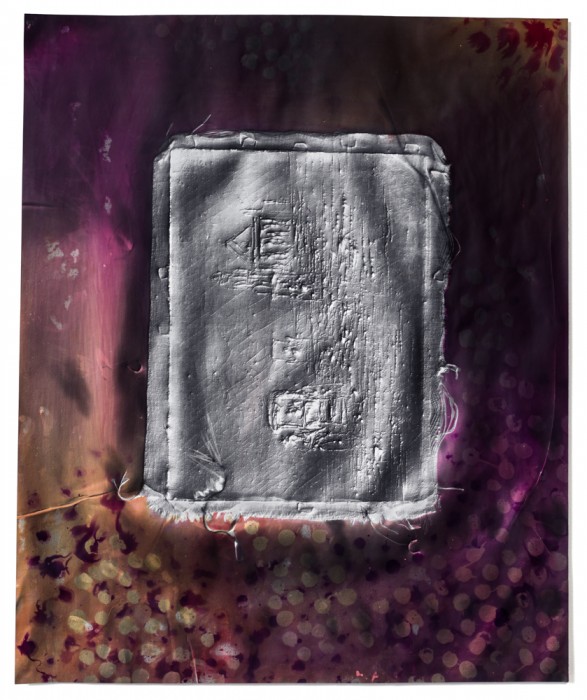

©Klea McKenna, Rainbow Bruise 11, Photographic relief (embossed gelatin silver photogram, fabric dye), 23×19”, 2021

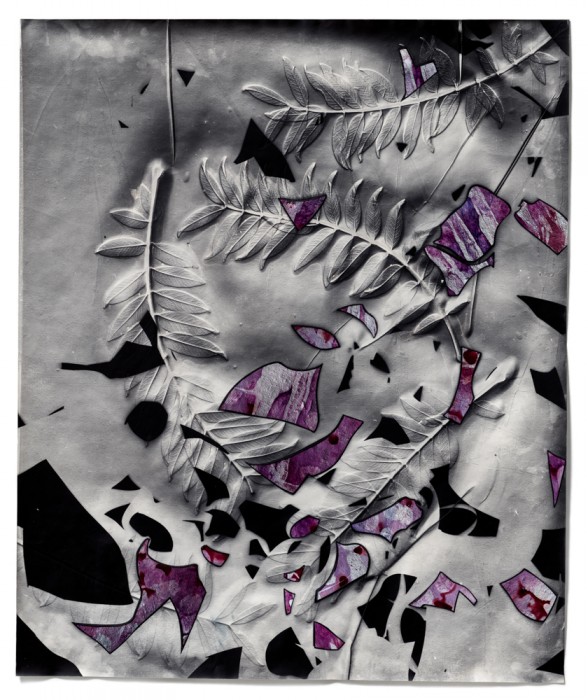

©Klea McKenna, Rainbow Bruise 1, Photographic relief (embossed gelatin silver photogram, fabric dye), 23×19”, 2021

Klea McKenna (born 1980, Freestone, CA) is a visual artist who also writes and makes films. She is known for cameraless photography and her innovative use of light-sensitive materials. Her work is held in several public collections, including San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA; Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, CA; United States Embassy Collection; Mead Art Museum, Amherst, MA; Museum of Fine Arts Boston, MA, and The Victoria & Albert Museum, London. She studied art at UCLA, UCSC and California College of the Arts. Klea is the daughter of renegade ethnobotanist, Kathleen Harrison and psychedelic philosopher, Terence McKenna. She lives in San Francisco with her partner and their young children.

Kim Beil teaches art history at Stanford University and is the author of Good Pictures: A History of Popular Photography. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter.

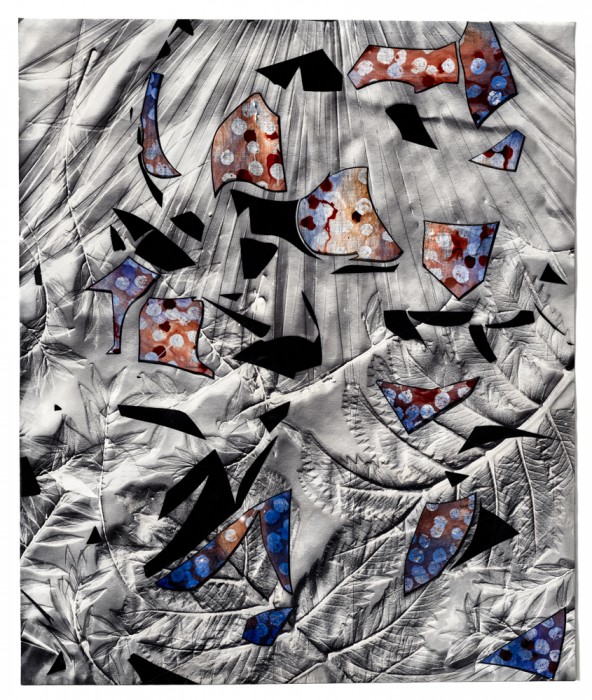

©Klea McKenna, Rainbow Bruise 7, Photographic relief (embossed gelatin silver photogram, fabric dye), 23×19”, 2021

Kim Beil: Your process now uses elements of printmaking, collage, painting, and photography. How did you first come to photography? How long have these other media been part of your practice? And, what excites you about bringing them all together.

Klea McKenna: I came to photography when I was about 12 or 13. My mom had an artist friend who was into Polaroid transfers and she taught me that technique and let me visit her studio a few times. Then I found a darkroom at the local junior college and would take the bus there after school. I was a dancer and I continued to be, but through my teens and early 20’s photography gradually took over as my primary artistic mode. Of course, being an artist is not an easy path, but compared to being a professional dancer it seemed kinder and more practical. My parents were extremely bohemian and I was raised in a rural hippie sub-culture so I didn’t really know people who had professional jobs, I had no model for that.

I’ve always used other mediums for my own pleasure and with my kids, but I didn’t consider it my “real” work. Photography was both my trade and my clearest voice. In the last few years I have chosen to stop compartmentalizing the various parts of my identity and interests and let them all bleed together. So there has been a gradual integration of photography, writing, filmmaking, printmaking, painting, motherhood and I’ve been more public about how all those things intersect. To viewers these shifts may appear sudden, but it has all been brewing under the surface for years.

©Klea McKenna, Rainbow Bruise 2, Photographic relief (embossed gelatin silver photogram, fabric dye), 23×19”, 2021

KB: Your work is often motivated by a sense of history, whether it’s a personal history, as you explored in your book The Butterfly Collector, that addressed your father’s legacy, or a larger cultural story, such as the history you described in Generation, your series that focused on textiles and women’s handwork. When does research come into the work—before you’ve started, while you’re working, or after the work is completed? And, what about these histories is inspiring for you?

KM: Yes, I would have liked to be an archeologist. Research has long informed my interests and my process, but I only started making that visible to others in the last 5 years, in the form of writing, artist books, process videos etc. Sometimes learning about a piece of history will spark the idea for a project (such as the soldiers who were stationed on the California coast in WWII to endlessly watch the horizon. This inspired my 2011 installation “Paper Airplanes”). Other times, I become enchanted by an object and I know I want to work with it, so then I research its origins and meaning. Most of the subjects I work with are fairly mundane and from the recent past, not precious or ancient, so it’s a combination of historical research, cultural observation and my own intuition about how our stories are embedded in the material world.

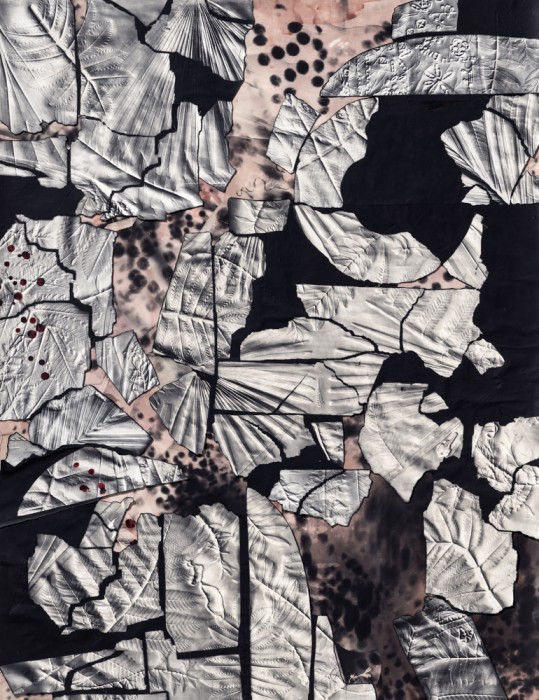

©Klea McKenna, Fossil Record 3, Collage of photographic reliefs (embossed gelatin silver photograms), fabric dye, 24×20”, 2022

KB: You’ve said that during the pandemic, you resorted to a kind of “clawing, desperate optimism” that the present moment is just part of a larger cycle. I love this description because it suggests that optimism isn’t just an accidental state, but one that can be created. How do you do this (asking for a friend)?

KM: I am not naturally optimistic, but I am resilient and I think part of that is the skill of finding interest, hope and meaning even in grim times. I think my “desperate, clawing optimism” is a byproduct of motherhood. I hear millennials saying “I’m not going to have kids because the world/country is too messed up” and I agree with that. However, I already have two kids, so I have to do the mental gymnastics to feel OK about that, which means zooming out and thinking really “big picture” about cycles within nature, humanity and civilization. Despair is not an option for parents of young kids because we cannot pause to feel it nor put it on our kids (I am grateful that at least I can put it into my art). I have to find a way to imagine a future in which my children can have meaningful, joyful lives, otherwise WTF am I doing? Personally, I don’t think that fighting to turn back the clock on our culture, climate, and crumbling empire is going to work, so I think the most optimistic thing we can do now is accept change and adapt to it by being flexible and building new models and systems. Living amongst the ruins does not have to be a terrible thing. I’m reading a book right now that makes this case much more eloquently and economically than I can. It’s called “The Future of Decline” by Jed Esty. It sounds dark, but I am finding it really hopeful.

©Klea McKenna, Fossil Record 2, Collage of photographic reliefs (embossed gelatin silver photograms), fabric dye, rag paper, 24×20”, 2022

KB: Could you walk me through your choice of objects for the collages in Rainbow Bruise? How do these things come together? What kinds of stories are they telling?

KM: I began by collecting old paintings, oil or acrylic on canvas, that were being sold at flea markets, garage sales and on eBay. I’m interested in objects that have had a lot of human attention poured into them, in the form of labor, wear, appreciation. These sort of amateur paintings are made with devotion and every bit of their surface is touched and rendered with care, then they are lived with for years and decades in people homes and often kept, not because they are beautiful, but because they are personal. They have meaning embedded in them which is not visible to the eye. I wasn’t interested in their subject matter but rather in their texture, brush strokes, flaws and unraveling edges. In darkness, I emboss them into analog photographic paper, then I cast grazing light across the resulting imprint, creating a photographic image told through texture. This process erases color and any pictorial representation and leaves only a map of the surface in all its minute details and flaws.

There is an arc to this work that is parallel to my own arc over the year and a half while I was making it. First there was erasure of these old images, then (through the pressure of my process) they began to break apart into shards and fragments and those shattered forms became a reoccurring pattern. Then I began to recombine all these pieces to build new artifacts. The images became increasingly layered hybridized and colorful as time went on. I felt like I was rebuilding on my own terms.

©Klea McKenna, Dig 1, Collage of photographic reliefs (embossed gelatin silver photograms), fabric dye, rag paper, 60×45”, 2022

KB: Although there were elements of collage in the arrangement of textiles in Generation, Rainbow Bruise uses collage more explicitly: sheets of photographic paper are cut and overlaid in your final works. Tell me how this developed and what it adds to the experience of the work?

KM: At first it happened out of necessity, I’m working with unique photograms that are hard to produce and impossible to replicate, so there are times when collage is just a resourceful solution and it also allows me control of composition that I don’t have while working quickly and in darkness, on the initial photograms. Then it became clear to me that this process of fragmentation and reinvention mirrors the content of the work and of the experience I was having and witnessing around me. Both my mother and my life-long best friend experienced violent traumas about a year and a half ago. These are the two closest women in the world to me, so we all went through it and it heightened my awareness of the transformation and reinvention that can come in the wake of trauma. The rainbow bruise.

©Klea McKenna, Cave Painting, Photographic relief (embossed gelatin silver photogram), fabric dye, 42×36”, 2021

KB: Your work seems to celebrate touch—and it really challenges a viewer to think about how tactility is represented on a (nearly) flat plane. This is endlessly fascinating for me: the work seems to invite touch in return, but of course, you can’t touch it in a gallery. How do you think about this interplay between vision and touch?

KM: It is the quality that I am most enamored by and I’m so glad that it’s what you are picking up on. My work has long been more about “the body” than may be evident at first glance. It’s not about looking atthe body, but rather about being ina body; sensory experience and perception and the gaps in it and the limited tools we have to express it. Photographic technology has been modeled after the eyeball and optics. To subvert that and make touch more primary than sight gave me a new way to read my surroundings. It felt like finding an encoded history written into the surfaces around me. When people visit my studio, I love letting them touch the prints and realize how 3D they are, how much information is physically embedded in them. I have made book covers out of embossed prints to try to share that experience with viewers more broadly. Photography is always a combination of evidence and fiction that’s what gives it power. Bringing other senses into it deepens the way our body experiences a piece of art.

©Klea McKenna, Ring of Fire, NFT of a digital collage of hand painted, analog gelatin silver photograms, fabric dye, shadows, 2022

©Klea McKenna, Wolf Mother, NFT of a digital collage of hand painted, analog gelatin silver photograms, fabric dye, shadows, 2022

©Klea McKenna, Blue Mirror, Photographic relief (embossed gelatin silver photogram), fabric dye, 49×41”, 2021

©Klea McKenna, The Glove, NFT of a digital collage of hand painted, analog gelatin silver photograms, fabric dye, shadows, 2022

Installation view of Rainbow Bruise at EUQINOM Gallery (photo by Henrik Kam)

Installation view of Rainbow Bruise at EUQINOM Gallery (photo by Henrik Kam)

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026