Photographers on Photographers: Tristan Sheldon in Conversation with Ron Jude

I selected Ron Jude to interview because his practice presents a deeply curious and genuine relationship with his subjects, the world, and the medium that I continually draw upon. His most recent project, 12 Hz, directly influenced the body of work that earned me a chance to participate in Photographers on Photographers. Delving into his older works stimulated an interest in the narrative and poetic potential of photographs and their ability to communicate beyond the boundaries of the frame, as well as the power of quieter, subtler imagery. Finally, I have a deep appreciation of the way he has integrated photography into his life as a means to wander, discover, and learn about the world around him. Discovering Ron Jude and his work has fundamentally changed the way I think about and make photographs, and so it felt right to take this opportunity to learn a little more from him.

Ron Jude’s work often explores the relationship between place, memory, and narrative through multiple approaches ranging from the use of appropriated images to photographs that echo traditional documentary methodologies.

Jude earned a BFA in studio art from Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, in 1988, and an MFA from Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1992. His photographs have been widely exhibited nationally and internationally and are held in the permanent collections of the George Eastman House, Rochester, NY; the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others. Jude is the author of twelve books, including Emmett (2010); Lick Creek Line (2012); Lago (2015); Nausea (2017); and, most recently, 12Hz (2020). An experimental publication entitled Dark Matter will be published in the fall of 2022 by Monogram in Belgium, and he currently has a traveling exhibition of 12 Hz, organized by the Barry Lopez Foundation for Art & Environment which will finish its run at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, TN in 2024. He has received grants or awards from Light Work; San Francisco Camerawork; the Aaron Siskind Foundation; the Friends of Photography and was the recipient of a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 2019. Jude is represented in the USA by Gallery Luisotti in Los Angeles and in Europe by Robert Morat Galerie in Berlin. He is a professor of art at University of Oregon and lives in Eugene with Danielle Mericle and their son Charley.

Follow Ron Jude on Instagram: @ron_jude

Tristan Sheldon: I’ve read in other interviews that you usually don’t begin a body of work with a plan, that your projects sort of begin as an act of wandering and discovery. In the short time that I’ve been pursuing photography, this has been my process as well. I’ve found that developing a plan before I go out to make pictures feels limiting and less productive. My favorite pictures are the ones that I find. You’ve said that when you were younger, working this way made you nervous and feel like you didn’t know what you were doing. This is an experience that I am going through right now, so it was really comforting to read that you eventually came to trust yourself and your process. I’m curious about how you handled this sense of self-doubt, how it may have influenced some of your early decisions in your career. I’m also wondering if you believe that the contemporary art/ photo world is any more or less receptive to the more personally expressive, perhaps less critically situated work that you tend to make?

Ron Jude: It’s generally true that I don’t have a preconceived idea of what I’m after when I first start something. I say “generally” because there’s always some basic decision making that starts the ball rolling—do I take the subway downtown, or do I drive out of town and walk into the woods? Do I make original photographs, or do I work with preexisting material? Do I want to dust off the view camera, or do I want to see what I can do in the digital realm? I know this all may seem somewhat trite and perhaps not relevant to what you’re asking about, but those fundamental decisions do get made, albeit somewhat intuitively and sometimes on whim, and can have everything to do with the work I end up making.

I rarely (if ever) set out with an “idea” and a specific subject in mind. My process is guided by the images themselves, at least at the beginning stages of a new project. I’ve learned to trust that by simply being in the world and having a basic curiosity about how photographs can alter, distill, and organize the visual chaos of lived experience, I’ll be led to things that I find worth looking at, both visually and intellectually. This requires a bit of a leap of faith and making some photographs without really knowing why. When I was first starting out, I imagined that successful photographers worked almost as if on assignment, with clear intentions and a deliberate agenda. It may be true that this is how some people work, but I’ve learned that we all go about this messy business in different ways and the hardest thing to figure out early on is which way works best for you. That requires a lot of experimenting and a lot of failing, which can be difficult if you’re trying to make work in the context of a degree program with deadlines, expectations, and professors who think everyone should work the way they do.

In terms of self-doubt, I’m afraid that never completely goes away, at least it didn’t for me. I learned to trust my process, but I think if you’re truly and consistently challenging yourself to push the boundaries of your work and explore new terrain, self-doubt is part of the bargain. But again, maybe that’s not true for everyone. I have had so many false starts and dead ends in making the work, so much indifference to and rejection of the finished work, that it’s hard not to let the doubt creep in. But I keep making the work because it seems like a worthwhile thing to do and it’s something that’s always given me more satisfaction than not. There’s the ego and there’s the work. I think it’s important to recognize the distinction between those two things, despite them being constantly intertwined.

As far as the art/photo world’s reception of the work due to its tone, that’s something I don’t really think about or let influence the work as I’m making it. Even though my audience has grown over the past couple of decades, I feel like I’m still making work for the same four or five people—the people whose opinion I trust and with whom I share an overlapping sensibility. The “art world” is a nebulous thing and although it’s possible to track trends of what’s being shown or published at any given moment, I don’t think that’s something you want to chase. If you do that, you’ll always be two steps behind and you’ll never do work in which you’re truly invested.

This might also be a language problem and what we mean by “critically situated.” I think work can be critically situated in a variety of ways, and that its expressive qualities, regardless of how pronounced, don’t exclude it from finding a footing in critical thought. I think in photography we sometimes confuse work that addresses social issues in prosaic, often didactic ways to be more “critically situated” than work that has just as much (often more) intellectual rigor but favors a nuanced philosophical and visual approach over one that’s prosaic, reductive, and polemical. There’s a humanist documentary impulse that runs deep through our medium that can be dogmatic in its insistence on the surface legibility of social utility. There are a lot of engaging, interesting ways into any given subject and I think it’s possible for a work’s visual and expressive qualities to support, rather than diminish, criticality.

TS: For several of your projects, such as 12 HZ and Executive Model, you have a very project-specific visual language that you develop over the course of working. After you’ve finished a project and put it out into the world, do you ever continue to make those pictures, or do you leave the style behind? For me, I would imagine it being very difficult leaving behind something so successful once you’ve developed it. Will you continue to make 12 HZ work?

RJ: When I finished Executive Model, I knew I wouldn’t revisit that way of working or that subject. The project was finished when I did the show at the High Museum in 1995, and to continue making those photographs would have seemed redundant and empty to me. I sometimes honestly wish I could find a way of working that I could plug into and just do for the rest of my life, but I always know in my gut when it’s time to move on. The difficult part, as you alluded to in your first question, is that I pretty much start from scratch every time I start a new body of work. Sometimes it can take a while to get traction on a new direction, but I think that sense of experimentation and uncertainty is an important part of the process.

As far as the 12 Hz work goes, I’m feeling a little more open-ended about that. I think as a body of work 12 Hz is finished. (The cap on a project these days usually comes when a book is published.) That being said, I think there are related, smaller projects that I will do that can still feel fresh and interesting and not like I’m beating a dead horse.

TS: I’ve read that Alpine Star, Emmett, and Lick Creek Line act as a trilogy of works that, while not directly autobiographical, are rooted in the experience of your childhood and youth. The projects work together beautifully, even though they were made in very different circumstances. I’m wondering about the process of realizing that you could contextualize all this work together. At what point in the process did it happen? To what extent, if any, did the existence of the three projects influence the conceptual development of the other.

RJ: The three projects you mentioned weren’t conceived of as a trilogy, but each one influenced the next in terms of how I was thinking about structure. It really wasn’t until I started putting Lick Creek Line together that I understood the interlocking pieces between the three projects as a trilogy of works.

Alpine Star and Emmett are similar in terms of how I was thinking about organizing collections of pre-existing, unrelated photographs into something that had a subversive nod to narrative and an arc that gave shape to the images. In both instances, I was working with photographs from a single source, with the common thread being the location—the small town of McCall, ID. Alpine Star was culled from The Star News, the town’s weekly newspaper. This was the newspaper that I grew up with since the early 70s, and even worked at for a short time in the early 80s. (I worked in the darkroom for a month one summer while the regular darkroom guy went on an extended vacation.) It was a publication that I knew intimately, as it chronicled the lives of the residents of this town, many of whom knew each other. I appeared in photographs in the paper throughout my childhood for different reasons, so it became a personal link to the community in addition to a repository for civic banalities and obituaries. It was a seemingly random collection of images and news from a working-class mill-town as it transformed into a resort town during the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Due to my connection to and fascination with the photographs in this newspaper, I collected and archived the weekly issues for over a decade. At a certain point I started thinking about the way the images worked in that context and how they could be reshaped and fictionalized to fit my own perception and memories of the place, much in the same way we all structure, narrativize, and filter our own experiences into digestible stories.

With Emmett, I became fascinated with my own early photographs, many of which I had no memory of making, or of the circumstances in which they were made. Sifting through piles of these images seemed like glimpses into another person’s life, with no narrative context for the fragments. In this sense, Alpine Star completely informed how I was thinking about putting Emmett together. Another similarity was that these photographs were made in the same place as the photographs in Alpine Star. The difference is that the scope of the images was narrower, having all been made from a single perspective, whereas the images in Alpine Star were more socially oriented and resided in the realm of collective memory. If you look at the two books side-by-side, you’ll see obvious similarities in basic pacing and structure. I think Emmett was more complex in its arrangement and arc, but it was a natural evolution of some of the same ideas about memory, narrative, and the past (as a philosophical notion) found in Alpine Star.

After having made those two books, I began working on Lick Creek Line. It was at this point that I saw the three projects as being related and began consciously thinking of them as a trilogy and of Lick Creek Line as the lynchpin. If you look at all three books together, you’ll see how they begin to inform and interlock with each other. Nothing on the surface would make you think of these works as having anything to do with each other, as they each draw from very distinct pools of images, but there are several clues in Lick Creek Line that bind the projects. For instance, the cover image of Lick Creek Line, as well as the images in the insert that accompany Nick Muellner’s short story were all pulled from The Star News, the source for Alpine Star. The prologue of rushing water images in LCL pick up where the epilogue of Emmett leaves off. Each of the three projects uses the same landscape and locations as a backdrop. More importantly, however, are the parallel ideas about narrative, memory, and place that run through each of the books. To me, this is what really binds them together. They’re each about the same place during roughly the same period, but from three completely unique perspectives. At the heart of all three is the fallacy of photographic empiricism. Although they each appear stylistically different, all the photographs were made with the same fundamental documentary impulse, and the naïve assumption that images can serve as a reliable narrative shorthand of lived experience.

Shortly after publishing Lick Creek Line I was approached by Karen Irvine at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and invited to bring all three projects together into a single exhibition. I saw this as an opportunity to make an argument for these projects functioning as a trilogy. We also made a publication called Fires, which wove images from all three projects together into a single printed piece. Whether or not the whole thing translated effectively as an interlocking trilogy is up to those who saw the show, but I was happy with how it all came together.

TS: Getting more specific into the long-term development of those bodies of work; One of my regular travel companions is a young man that, for some reason, I tend to photograph more than anybody else. People tease me that he’s my muse, they joke that I must be in love with him. I don’t know why I make so many pictures of him, or what I may eventually do with the images. When I was reading about Emmett, I was fascinated to discover that many of the portraits in that body of work came from a remarkably similar situation. I’m wondering how you felt about those pictures before you made Emmett, both as images and as a photographic tendency of yours. Maybe it’s just because I’m new to all this, but when I make pictures or types of pictures that I really enjoy, that become special to me, but I don’t have any idea what I’m ever going to do with them or what context I’ll be able to show them in, I get a sort of anxiety about it. Like, “this picture is really great, I can’t let it go to waste!” Do you have pictures like that, and if so, what do you do with them? Did you feel any remorse that those portraits in Emmett, or really any of those pictures, hadn’t yet found a place to live?

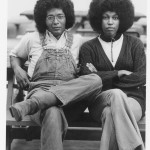

RJ: It’s funny that you have been teased about making photographs of your friend. When Emmett first saw daylight as a “project”, Doug DuBois said the same thing to me about my main subject, my friend, Ken. I have no idea, even after serious reflection, why I made so many photos of Ken. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, Ken was a good friend, but I don’t think I would have called him my best friend. There must have something innately photographable about Ken—that feathered hair, those GTO t-shirts… Or it could have been something as simple as consistently finding myself in interesting circumstances with Ken, whether we were repelling off the side of a mountain or watching funny car burnouts at a drag racing event.

In terms of how those images from that period of my life came to constitute a “body of work”, I made all those pictures without thinking at all about anything remotely related to art. Those photographs were the byproduct of my advanced amateur photographer’s enthusiasm for the medium and my desire to make photos of everything happening around me. (Decades before we all began sharing way too much of our lives through photographs on Instagram and it became a mind-numbing banality.) I had no expectations for them other than to make them and see how things looked in photographs. So, I had the benefit of not lamenting over how the images would be used. I was satisfied just making them, looking at them once, and moving on. As I mentioned in my last answer, those photos only became interesting to me long after they were made, and for reasons entirely unrelated to why I made them.

All that being said, I think it’s a good idea to not over-analyze why I’m making photographs during the process of actually making them. There’s plenty of thought that goes into things once I start piecing the puzzle together, but I don’t think it’s a good idea to overthink the basic impulse for taking a photo. The big lesson for me in making Alpine Star and Emmett, was that I can think of all my images as raw material that is given shape and finds meaning through context. It might be that those favorite photos of yours find a home in a project soon after you take them, or, just as likely, it could be several years down the road that an image transcends being a “favorite” and becomes a useful component in something larger. Or, depending on how you use and think about the medium, those “favorites” could themselves constitute a way of thinking about image making and seeing the world through photographs. But for me, taking the photograph is only half the equation. The work really crystallizes into something once there’s a dialogue between images. The key, I think, is patience, and a faith that your photographs will lead you somewhere, you just have to pay attention to the big picture and not get seduced by your favorite images into thinking the work is done. Pretty much every book or exhibition I’ve put together I’ve started my initial layout with several “sure bet” images that ultimately don’t end up in the final edit because they don’t support the larger structure. I know there are some photographers who might cringe at that notion and say that it’s all about the image, but I think we all have different ways of working and different priorities.

I’ll finish this now long-winded answer with a practical point. Every photograph is worth making, if for no other reason than it’s useful to practice. It’s like playing a musical instrument—you need to practice, or you get rusty. When I’m in the middle of a project and things are moving along and I’m shooting consistently, I find it much easier to get into the zone and see the images I want to make when I go out to shoot. If I haven’t shot in a while due to daily demands or whatever, it takes a while to warm up and start making worthwhile images. I’ll often take my camera out with no intention other than to practice and occasionally I’ll surprise myself with unexpected and interesting images that point me in a new direction. That was the case with 12 Hz.

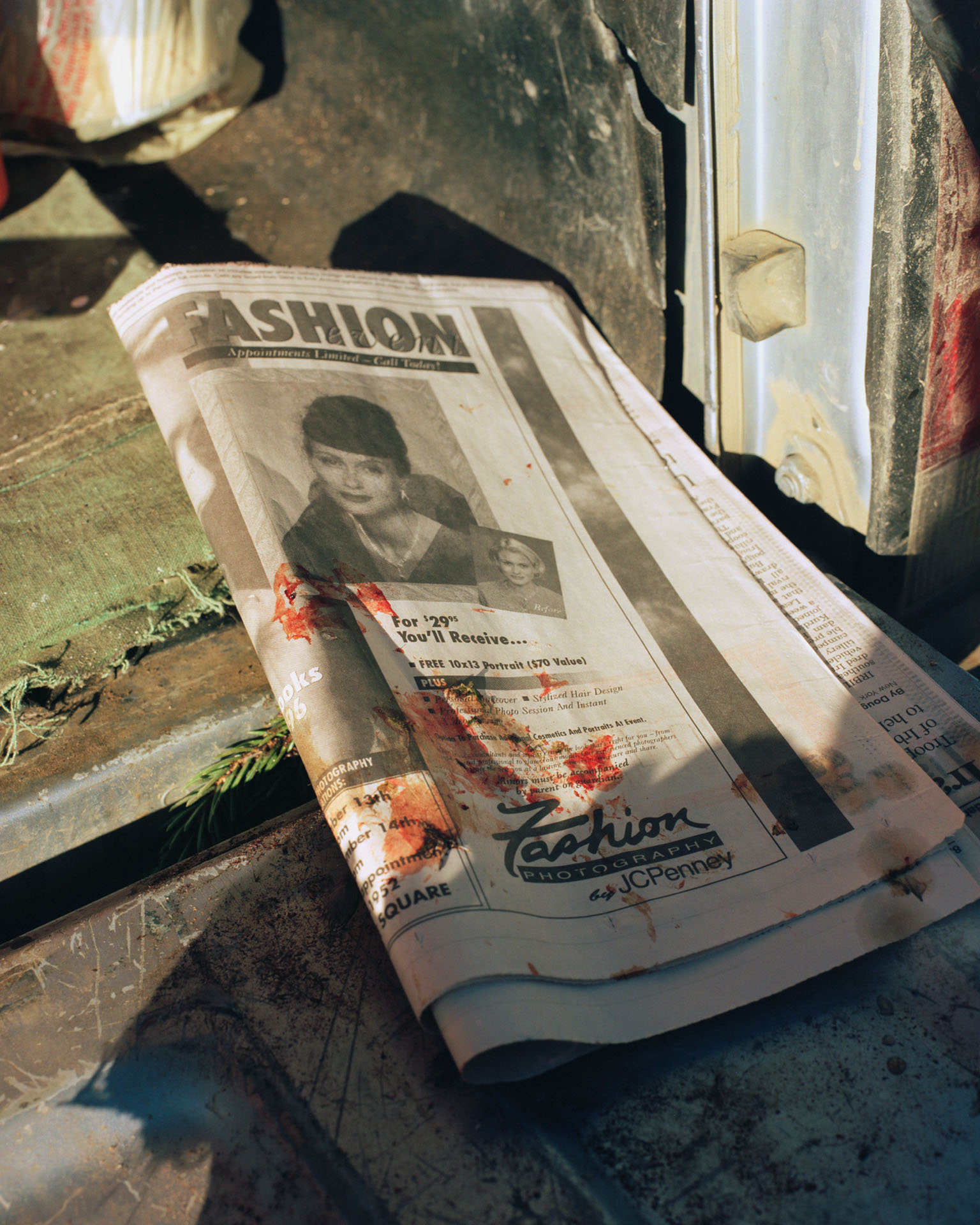

TS: I had been meaning to ask about something that you started to touch on with that last answer. For me, what was so initially captivating about photography was the feeling of making an individually successful image. When I discovered 12 Hz, it resonated with me so much because, to me, all the images in that project struck me instantly as sublime, or awe-inspiring. So, when I went back through your works and found projects like Nausea and Lick Creek Line, I didn’t really know what to think at first. I didn’t even know if I liked it. But something about Lick Creek Line in particular kept me coming back, and every time I went through the sequence, I found more brilliant, beautiful, and subtle little moments, such as the specks of blood on the newspaper, or the gesture of the trapper working with his back turned to the camera. I see this as one of the first instances that I began to appreciate the medium beyond the success of “the image.” And yet, I still find myself obsessing over trying to find ways to cram all my “good” pictures into one project, which is starting to feel like beating a dead horse, to the point where I’m starting to question if the pictures actually are “good.” So, I guess what I’m looking for is any insight or elaboration on the process of culling the “sure-bet” images. How do you step back from the work and realize that an aesthetically strong picture actually weakens the narrative strength of the project? Do you ever have a hard time removing a picture that you previously considered integral to the body of work? Is this something that you do primarily alone, or do you rely heavily on peer feedback?

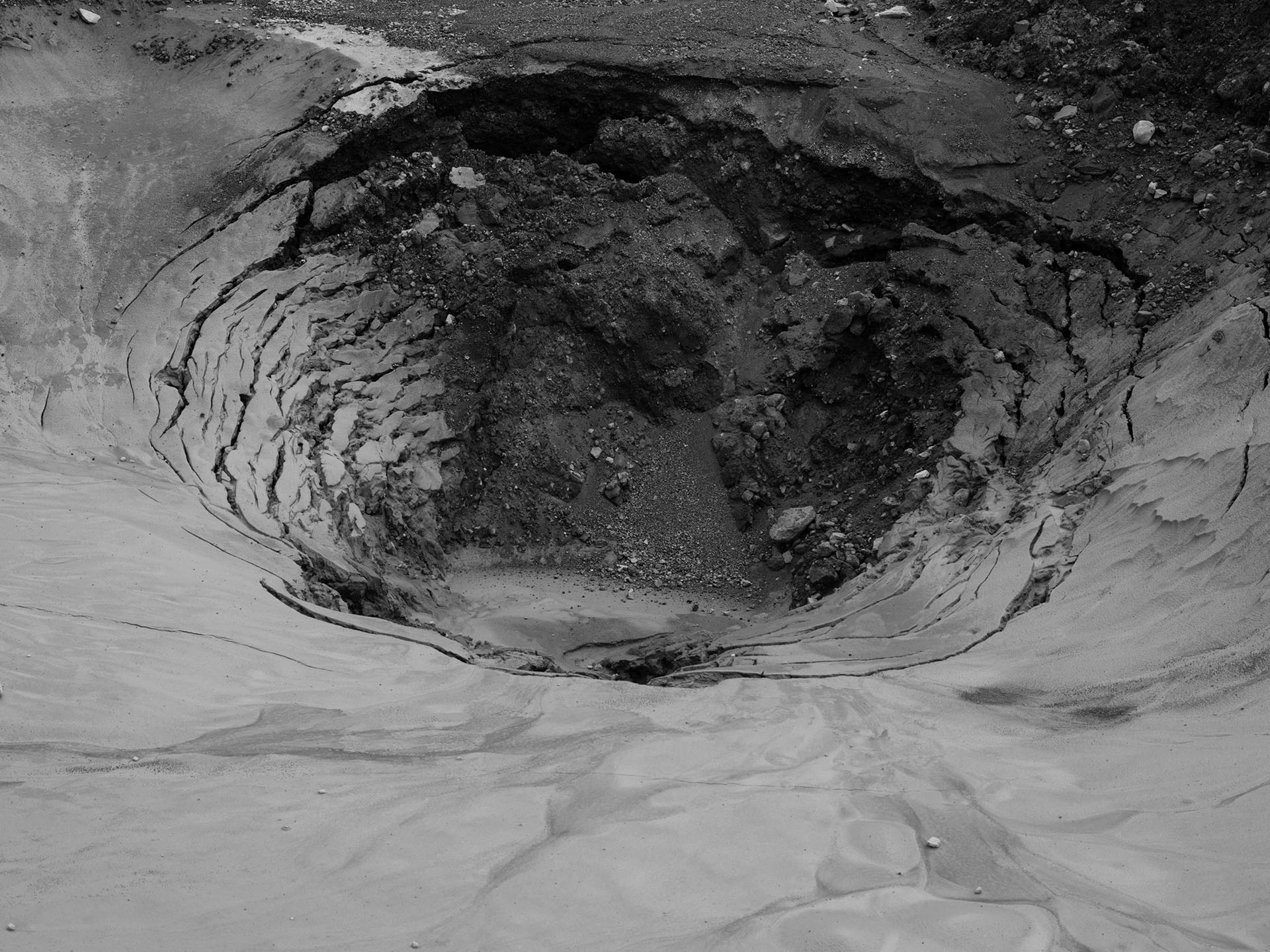

RJ: There’s a lot to sort through here, but this is a good line of questioning, and it touches on something that I think I’ve somewhat miscommunicated about my work in past interviews (or artist talks, or whatever). I tend to emphasize the importance of the sequential structure in my books, which I think unfairly diminishes the investment I’ve always had in individual images. While it’s true that I think it’s important to understand what an image contributes to the overall arc of a sequence, my process has always been that in editing I first consider images based on their individual merits. That doesn’t mean, however, that if I make an image that performs particularly well on its own that I’ll include it in a book at the expense of everything else that’s in play in a sequence. But that also doesn’t necessarily mean that the image is cut from the body of work if I don’t use it. I see a “body of work” as something distinct from what the book is. Books for me are simply one incarnation of a project and they don’t necessarily represent the entire body of work as it might appear in exhibitions or other contexts. (A good example of this is the banner image for the traveling exhibition for 12 Hz. (Black Ice with Glacial Melt, 2019.) It’s used as an important representational image for the installation, but it never found a home in the book sequence. It simply didn’t work in the book, even though it was one of my early “favorites”. The exhibition, however, is a different beast, and it has a meaningful place in that context.

When I made most of the photographs for Lick Creek Line, for instance, I wasn’t thinking about a book sequence at all. I was simply trying to craft what I thought were impactful individual images, without regard to how they would work in a sequence. Each image gets its own consideration. The creative act of making photographs, for me, resides in a different part of my brain than the creative act of piecing the puzzle together as a book, and I think each are equally important. While it’s true that with certain projects, like Lago, for instance, I was thinking about how the photographs might operate in a larger context as I made them, the process of shooting still favored the idea of the importance of the individual image. This may seem a bit convoluted and contradictory, but I think of the overall process of Photography as being split into two parts: field work, which is an unpredictable process of chance and discovery, and the equally important work of editing and giving form to the work through selection, sequence, and context. Additionally, there are additional decisions like scale, materials, and presentation that shouldn’t be left as an afterthought. Each step in the process can make or break “the work”. But to be clear, I highly value the individual image and I always have, for every project. If one of those “favorite” photographs doesn’t find a home in a book or an exhibition, it doesn’t mean that it has no value and will be discarded. I think it’s important to have a certain amount of patience in terms of when an image might see the light of day.

To your point about 12 Hz operating differently than a book like Lick Creek Line, that was a deliberate departure from a way of working that I was beginning to tire of. With 12 Hz, I wanted to emphasize the individual image, even within the context of a book or exhibition. I wanted to think about how a sequential structure might be comprised of images that work in the same spirit but were less dependently interlocked within that sequence. Of course, at the end of the day, a sequence is still a sequence and it’s impossible to move completely away from the narrative impulse, but I think 12 Hz, as you pointed out, is operating differently than some of my earlier books. This was by design.

In terms of finding the necessary objectivity to edit effectively, it does help to have a small peer group whom you trust for input and advice. I have several friends who have different perspectives on things, each of which is valuable for different reasons. My advice to anybody when it comes to getting feedback is that outside perspectives are helpful, but you don’t want too many cooks in the kitchen. You really need to find those few people who know your work and understand your goals as an artist. It’s also important to remember that everybody’s opinion, no matter how much you trust them, should be filtered and that you always have the last word on your own work. I don’t mean you should be unnecessarily stubborn in receiving advice, but you need to consider the perspective and values of the person offering that advice and filter it accordingly. Sometimes, however, you’re going to hear things about your work you don’t want to hear, and you’ll know deep down that they’re right. You need to trust that, too.

Tristan Sheldon was born in Rochester, New York in 1996. He grew up in Columbia, Missouri, and he is currently a senior at the University of Missouri seeking a BFA in photography. His work has been exhibited locally and has been featured in numerous group exhibitions and publications.

Follow Tristan Sheldon in Istagram: @tristan__sheldon

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024