South Korea Week: Hwang Yezoi: Those With Worms

Arts and culture movements develop as various societal forces ranging from economic to religious demands come together to invoke existing norms and value systems of that period in time.

The five Korean female photographers presented in this year’s series all come from the same contemporary cultural movement while varying their generations and viewpoints on ideologies and societal issues. As the modern history of Korea has seen major economic and social changes, different generations have different perceptions and experiences on how such societal changes have impacted their lives.

A current trend in Korean society today is to create new verbiage and words for everyday expression. Among those is a now-mainstreamatized neologism called MZ generation which stands for those who were born between 1980s and 2000s, a combination of two generations: millennials and generation Z. What’s considered unique about the MZ generation is their familiarity with the birth of widespread digital media usage, a sense of strong individualism propelled with a need for convenience and efficiency, and a need to seek differentiation from others. – Sunjoo Lee

The first female artist that I’d like to introduce in this article is Hwang Yezoi, a perfect example of an MZ generation, born in 1993. She is an up-and-coming photographer in the Korean MZ generation scene, and I came to pay special attention to her work given her focus on women rights and the politicization of bodily concerns in society. Her parents took great pleasure in collecting memories, and through their lifestyle, Hwang effortlessly picked up photography. She graduated from Anyang Arts High School and Kaywon University of Arts, majoring in Photography at both institutions. Rather than taking a grand, sweeping discourse, she collects personal narratives and intimately observes society through individuals’ emotions, relationships, and bodies. She has published photo books titled mixer bowl, season, Mago and a prose book, imagining the caring worlds .

Hwang Yezoi received a strict photography education starting from high school all the way to university, which was motivated by the oppressive environment of her life growing up. With this intimate experience, the artist has developed a strong personal photographic language that is free from the concept of uniformity and is strongly opposed to social coercion. In addition, her work shows the freedom and honesty of the MZ generation, as well as the transcendence of overcoming generational pain.

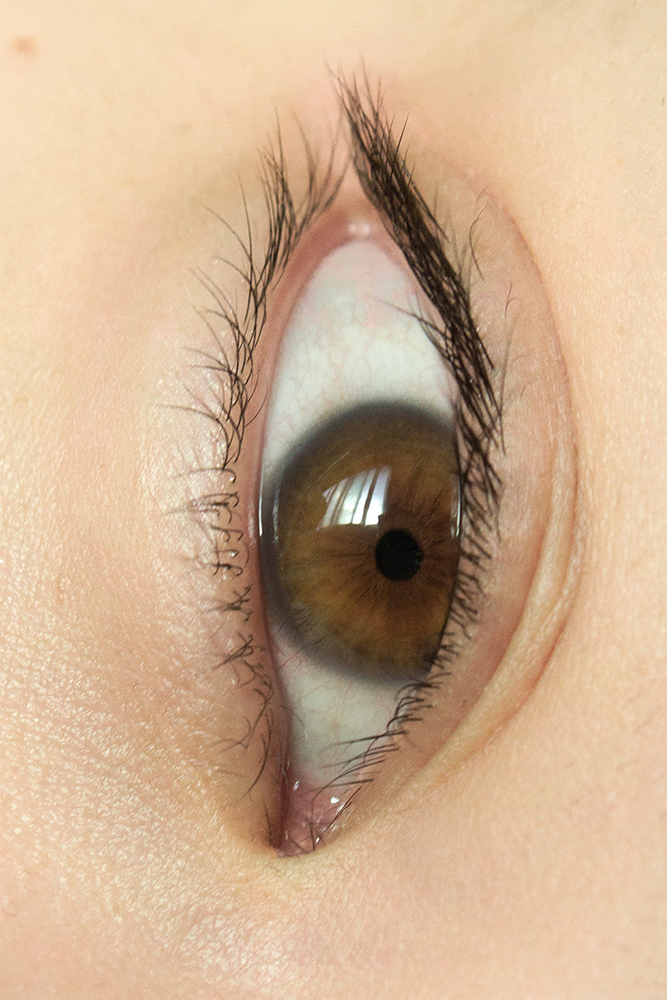

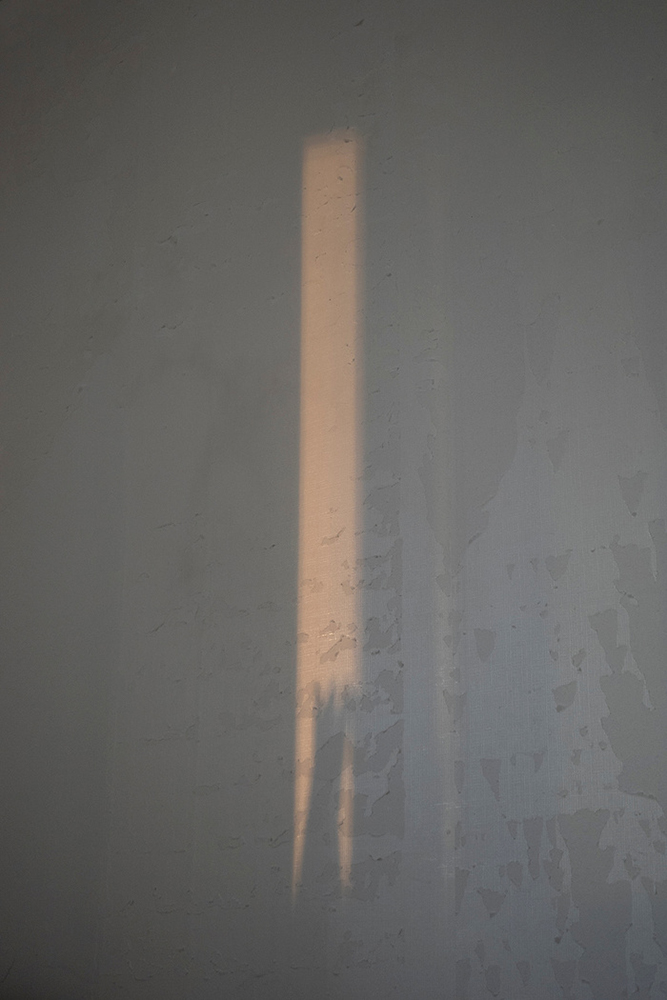

Season and Mago and were her debut exhibitions showcased during her graduation. Together, they were a critical examination of ‘womanhood’ and ‘love’. The artist’s photographic gaze on her women subjects is tense; she brings a sense of unease to the viewer as one does looking out from an edge of a cliff. Hwang’s Season is a work that depicts the three women in her family. In various compositions, she shows the relationship between the artist’s mother and older sister, and the relationship between her older sister and the artist herself. In Mago, the scope of the subject expanded from her family members to recording the body of an unfamiliar woman. The artist projects her own life to express the existence of a woman, but not to shine light on the topic of womanhood as an issue sought out by social demands, but through her own personal desires to hide her pain from familial trauma. The series also aims to expose the shared, human experiences of anxiety, pain, and absence that coexist in the viewers’ lives. This phenomenon is one of the special functions of photography — the ability for the artist and the audience to share and communicate through visual language.

Follow Hwang Yezoi on Instagram @yezoi

“I was small and I wanted to be separated from mom early, and mom had to tie her two legs up and live like that for 2 months just to save me. Life frequently came and went through that stomach, but birth was seldom came. I was the third to be born and the second to survive. There was a life between me and my sister who was born first. The master of that life was female, like us, and it was difficult for everyone to take their eyes off her. Although she is a phantom whose existence I never encountered, but it would’ve been the same for me too. When I mentioned the phantom, mom replied that she was sad, that she was terribly sad.

The hours passed with a dying daughter in the arms, belong to the realm of the uncountable. The shape and symptoms of 10 months disappeared. There was no name. The doctor said there was no other way to blunt the edge of loss than to create someone new, and that someone was me. I am the name created to offset a loss. The fact that I cannot determine my own age, that the axis of time keeps on oscillating, could perhaps be the contact between the phantom and me. I kept on mourning.” — from “Mago” by Whang Yezoi

This is from Hwang’s artist note.

The artist begins to communicate with the world by using visual language to describe the lives of the women in her family. Shortly after her mother gave birth to her second daughter, the baby did not survive, and her mother suffered from immense grief. To overcome her trauma of losing her newborn, her mother took a doctor’s advice to give birth to Yezoi. The author presents this private family story through the photographic medium with a multi-layered interpretation of the intimate events and various emotions that her family members experienced. The subjects in this work are depicted as those who carry different wombs — her mother, eldest sister, and the absent daughter (expressed as a ghost by Yezoi).

Beyond photography, Hwang is also involved in writing, video and film production. Imagining the caring worlds is one of Hwang’s writing publications which contains a collection of essays.

Hwang is a multidimensional artist who leans into the visual, spoken and written words of expression. In our interview, she frequently used the words “absence, anxiety, and mourning.” These seem to be the keywords that define her work.

The artist illustrates her anxiety around the past and future absences in her life through the photographic space. This intense anxiety coalesced and the concept of “absence” formalized in Hwang’s mind throughout the years as she overcame many tragic family events such as witnessing the failure of her father’s business, her mother running away for ten years, experiencing various illnesses her family members faced and the loss of her mother’s newborn.

“My name

so pretty, you could’ve been Yeji.

You came first

and I trod on Spring first, so who’s older?

We did not welcome the bloating stomach.

At times, we wanted to be born, in the time you discarded. We waited for that point of falling.

One day, I was lying in bed with mom. Mom said she’d like to have me shrink and go into

her stomach. With the body that cannot lactate, she asked if I’d like to have her breast in my

mouth. I rolled her breast in my mouth several times and weaned off. As if scalded, my tongue

left numbing traces. The face, restored to origin, let up with a bright smile. The smile was

dazzling bright. A myth unfolded just before my eyes.

The moment of birth marked the starting point of a chronicle called woman. Born from a

woman’s body, borrowed a woman’s body and the woman was loved. Of a woman, as a

woman, and so is woman.

That name feels quite extensive to me. A noble facial expression is made. The collapsed

backbone became a ridge, and the cracked skin became a stream. We draw a circle holding

each other’s wrist. We sing. We are us. As bloody as it can be, it is creation.”

-From artist statement Hwang Yezoi

I met artist Yezoi Hwang at a cafe located in Bogwang-dong, Seoul, one of the hot spots for young artists these days. As I waited for her, the particular sounds of the cafe music and gentle conversations seeping through the MZ crowd made me feel like an outsider in this microcosmic world. The unfamiliarity was short-lived; as soon as I met Yezoi Hwang, we were connected with deep empathy for each other.

Sunjoo Lee: Most Korean photographers have a tendency to major in photography in college and start their career as a photographer, but you chose to study photography since high school. Was there a reason that led you to choose photography as your career path at such an early age?

Hwang Yezoi: My parents’ influence was the biggest factor that led me to major in photography. My parents were good at collecting and documenting ideas and materials. They loved engaging in such practice. My father in particular, was diligent with the process of recording. He was, what you might call, a collector enthusiast — collecting stamps, writing diaries, and taking pictures. When I was young, I was in awe of the way my father intricately handled the camera and took pictures. It was then that I developed a strange admiration for my father’s ability to capture moments. Thus, the root of my love for photography stems from my positive experience growing up alongside my father, who actively engaged in photography. As soon as I had the chance to hold a camera in my hand, I realized that there was something inside of me that quietly supported this connection. It felt so natural to me to discover a language beyond words; and that was, the visual language. After that personal experience, I pursued a high school that had a photography department, and further, I majored in photography at university.

SL: I believe that photographers’ conceptualization of photography varies so widely given their unique experiences of coming to the medium. In particular, it seems your relationship with photography was bound to be inevitable. As such, what does photography mean to you as a medium?

HY: Although I don’t think of myself as passive or timid, the world seemed incredibly uncomfortable and foreign to me until I met photography. It was difficult to live in a world where so many different types of people had to coexist in one space. In particular, I faced challenges adapting to the microcosmic environment of a school setting.

Whether it was going to school or building relationships with other people, I had a hard time getting along with the world and communicating within it. And it was photography that taught me how to communicate with the world at the tempo that felt comfortable to me. In other words, photography was a strong guiding force in helping me to come out of my shell.

SL: You received your photography education within a system established by the older generation. Nevertheless, I witness your ability to go against the traditional methods of photography and you’ve developed your own sense of photographic lens inspired by the MZ generation. I’d love to hear more about your experiences at school and how that influenced your artistry. Please introduce the artist’s experience and influence on photography education from high school to college.

HY: I chose the Department of Photography at Kaywon University of the Arts because of professor Heung-geun Oh, and his unique approach to handling his subjects. I was inspired by his work and thus, wanted to learn under his guidance. In the professor’s class, the word “anxiety” was frequently discussed. This struck a strong chord in me. His method of teaching felt precious to me, and to this day, I carry his wisdom throughout my career: one that I don’t think will leave me for a while. As such, I believe my photography is distinguishable from those of the older generations and from the formulaic-ness of the institutionalized education system because I got to fully experience the inner feelings discovered through photography with the professor.

SL: So it seems as though your education that stems from a rigid system has still found its way to being an important, fertile soil for your photography career. Nevertheless, you seem to have your own way of exploration and growth in perception when it comes to your photography. How do you do it?

HY: I’m always actively engaged in seeing, and I take it upon myself to discover necessary changes that need to occur within myself. I consume visual stimuli, such as photos and movies, and try to crack my internal emotions or thoughts. For me, External stimuli are either found in conversations with others or obtained from experiences in society.

Besides being a photographer, I also teach photography. I am constantly stimulated by the wide-range of generations I come across in my classes — ranging from those in their late teens to their 60s. Engaging in other people’s experiences challenges me and shakes up my internal compass.

SL: Let’s pivot into your work and exhibition. I am interested in your thematic choosing of ‘womanhood’ and ‘love’ in your work. What made you choose the topic of women?

HY: I started working on the theme of “womanhood” in , as part of my college graduation work. It was a series of pictures of my mother and my sister. Rather than going through a rigorous conceptualization process, this series came together in an organic way, given the circumstances of what my family was going through. Before this series, I didn’t have it in me to explore broader societal concepts without resolving the tragic narrative that ran within my own family and myself. I had too many feelings of internal conflicts, misunderstandings, and doubts to figure out before diving into other topics. As the first stepping stone in my photography career, I had to solve my greatest internal sorrow — which was the deep sadness and misunderstanding that took place between my sister and my mother. That is how I got to taking photographs of my mother and sister.

To me, a mother figure was an unfamiliar and insecure one.

My mother ran away from our family for 10 years, and she left a huge void during a time when my sister and I needed the most of our mother’s love. Her absence reminded me of the experience of the absence that was and the absence that was to come.

The female body naturally became an important symbolic and literal vessel in my series, given the anxiety I experienced due to my mother leaving. In addition, with the absence of my mother, my older sister took on the role of a mother.

In all, I wanted to tell a story about the dynamics of women family members and to show the emotional imbalance of a family with the absence of a mother. Further, I wanted to show the subtle moments of understanding and conflict that arose between my mother and sister.

Visually, the photos are supposed to be mundane snapchats of the two subjects. I never imagined that those photos could become works of art and resonate with the audience. The photos were initially taken with the sole purpose of healing my sadness; they ended up comforting so many others who were strangers to my family. I was surprised that I got the attention of photo magazines. The fact that this particular series resonated and brought solace to so many others gave me the strength to start expanding on the lives of other people through the body of unknown women.

SL: What kind of personal connection do you have with the keywords, “absence, anxiety, and mourning” with the theme of “womanhood”?

HY: These keywords encapsulate my photos in and in my photo essay titled, . The words contain the story and meaning of the sadness that has affected me since childhood. The sorrows that ran through my life were the misfortunes that came one after another in my family.

Anxiety, sadness, and fear were frequent emotions that emerged through the absence of various familial events that occurred: the failings of my father’s business, battling family illnesses, and overcoming my mother running away. I always had to think about the departure of one of my family members, and that gave me tremendous anxiety. It was an experience of unhappiness as I recalled the circumstances I was in. Such a process of growing up gave me the sensitivity to sense the nuanced characteristic of the anxiety emotion. As I developed an emotionally-sensitive attitude in my youth, this way of thinking inevitably translated into my visual verbiage as a photographer.

The word “mourning” comes from the trauma and loss of the second woman in our family who came between my sister and me. It is said that my mother gave birth to me as a way to solve the loss and depression of losing that child. Through the series, I wanted to provide enough time to mourn and bring a feeling of comfort towards women’s bodies. I wanted to express the work in a way that feels divine — a mixture of mourning and consolation. I think everyone experiences absence. I believe that experiences such as these that involve women’s bodies in any form of life should be comforted and welcomed rather than be seen as a shame and hidden away.

SL: How did you want your work to be delivered and did you intentionally intervene in some portions of your work?

HY: I wanted my work to be seen and experienced through a series of sequences rather than as a singularly packaged concept. Therefore, my work is hoped to be seen as metaphorical rather than as a directive.

I hope that people of all walks of life — those with a blank slate as well as those with similar experiences — can all find some portions that resonate with their personal lives. But importantly, I wanted to maintain an unshakable axis for the “female body” as a subject. In order to do so, I started with my sister’s body and then expanded the subject matter to landscapes or bodies of completely unfamiliar characters. From then on, portraits of other women began to be included. I took pictures of models who saw their body as a place of struggle, and of those who experienced a state where a woman’s body was deemed as a war zone. The close sympathy developed with female models and their experiences made it possible to organically expand my line of work rather than feeling like I had to go through a pre-planned process.

SL: So you took these snapshots using your Hasselblad film camera without a tripod. What was your reasoning for that?

HY: Unlike digital photography, which is favored by the MZ generation these days, I prefer film. I started learning photography in a black-and-white darkroom. To be honest, the black-and-white film printing process gave me a lot of fatigue, but that fatigue was good for me. I have come to respect the long waiting time as it is part of a meaningful process toward a quality art form.

The delayed time it takes for films to develop feels similar to the pace of my own growth clock. I consider myself to be a very censored person. Film work requires careful censorship until the image is finished. I need to be careful about the completeness of the image, and the sense of serendipity and chance is often found only in film work.

I have two reasons for why I shot without a tripod. First, I didn’t come to photography to achieve technical perfection. Second, it feels disingenuous and unnerving for me to hold something in place. The physical connection between my camera and myself is important in my work. I have a sense of rebellion against perfection.

SL: Can you tell us about your future plans as a photographer and how you want your self-portrait to be depicted in the future?

HY: During my exhibition, I experienced an unexpectedly positive reaction from many visitors. I received letters from many women who sympathized with my life, and I also gained a lot of interest from other photographers. I realized that photography is not something I do alone, as I get the feeling that such a reaction from the audience fills the empty space of my exhibition.

I thus believe that photography is actualized when it is met with others’ gazes.

I plan to continue my future work as a series of sequences that build on the works of the previous stories. As my work started from my family and has expanded to broader topics of on body and women in society, my next layer of work will be a process of discovering important words such as relationship, mourning, and anxiety. I am also interested in the written language. I am aiming to release a poetry book sometime next year. A book on poetry is also expected to be released next year.

I don’t want to bind myself to a single genre. Whatever the story or event, I have a great desire to explore the emotions in the moments that they unfold. I still want to discover a lot more and do not want to limit my identity. Methodologically, I would like to express the current series’ narrative in a traditional darkroom photographic method.

In a fast-paced world, I plan to work on projects that require longitudinal time.

Inspired by the book, “My Private Property” by the poet, Mary Ruefle, I hope I reflect a sense of wisdom and innocence as I grow of age.

Young People These Days

Unlike how her photographs were clearly confirmed to resonate with unspecified individuals, her photographs were somehow omitted from the genealogy. Being listed in a specific genealogy isn’t always something to welcome, of course, but it is strange that the photographs of a person who majored in photography since high school through university and received institutionalized photography education, the photographs that secured a specific and definite audience when compared with those of any other artists, such photographs which receive much feedback online and in the fashion industry, are in a lukewarm relationship, particularly with the visual art industry. Yezoi Hwang seeks the answer from reading comprehension. In the world of photography where only photographs of similar types can be understood, Yezoi Hwang and her colleagues’ photographs are closer to a foreign language that cannot be read. Newbies always know what old hands do. They are even more incomprehensible in an environment where works of the old hands are passed down to them, as if prototypes that they should be exposed to repeatedly and learn. However, to the old hands, newbies are mere ‘incomprehensible young people these days’.

Whipping

The exhibition Mago only deals with woman. I can infer the political opinions that form naturally when an exhibition deals with only woman. Such opinions will be enormously defensive and intimidated. I can imagine someone armed with political correctness, piously extolling these photographs, trying to persuade themselves saying that they are meaningful political gestures in the Korean society. However, just as Yezoi Hwang did not demand anything from the subject, we don’t need to demand something from the images. This is because, there is no need to offer a specific reading method to the people who are already a part of a very old and a long story. A specific role and demand rather lock up photographs in limited time. The objects and figures Yezoi Hwang captured do not ask or long for something. This is not to say that they don’t have independence. To those who allowed others to ‘take photographs of the body filled with trauma’, independence is not something granted from the outside. What must be required to sense the power their existence holds? Here, the whipping called Yezoi Hwang, does not function as a catalyst which accelerates speed or share something spiritual. This whipping only wants to enable replies.” — From The Lonesome and Tranquil World of Mago / Suzy Park (Curator / AGENCY RARY)

Sunjoo Lee is a mixed media photographer based in Seoul, South Korea.

Lee’s extraordinary artistic sensibility that was once portrayed through her voice is now visible through the works portrayed through her camera lens. Her photography focuses on a unique lyrical journey into her personal life. She explores her past, present, and future world in a temporal and spatial perspective.

She received a BA in Music from Ewha Women University, a second BA in Photography from Chung-Ang University(Academy credit bank system), and an MFA in Plastic Art & Photography from Chung-Ang University Graduate School of Photography in Seoul, Korea. In 2019, she was awarded into the 11th cohort for the prestigious artist residency program at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary Art. Through this residency, she’s currently working on her upcoming series.

Lee’s acclaimed works have been exhibited widely throughout the years in South Korea. Most recently, she had her solo exhibition at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary art, Gwangju Korea. She’s also showcased at Gallery Now, Gallery Gong, Gallery Guha, and more in Seoul, South Korea. Her works are permanently displayed at the Haslla Arts Museum (Gangneung, Korea), and YoungWol Y. Park (Youngwol, Korea).

Her work at large, incorporates everyday objects and subjects to make visual sense of the complexities of human emotions and feelings derived from the intangible, such as music. Her photographic inspiration stems from her experiences of living and travelling abroad. She extracts the memories and various emotions born out of the human connections she’s made during that time of being in foreign spaces.

Building on this conceptual narrative, her work has landed her multiple recognitions, from the 2019 Critical Mass as a top 200 Finalist (USA) to the 1st Place Richards’ Family Trust Award during the 25th juried show at the Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, USA). In Korea, she was received the Dong Gang International Photo Festival’s Now and New Exhibition award.

Follow Sunjoo Lee on Instagram: @sunjooleephotography

Thank you to Sejin Paik for her excellent translation

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024