Germany Week: JENS KNIGGE

This week Lenscratch will turn its sights upon the artistic output of German photographers who present a broad array of the personal, social, historical, and political influences of life in contemporary Germany. Germany’s contributions to the photographic realm are extensive from the earliest days of the genre. From August Sander’s People of the 20th Century, a portrait study of all strata of German society, to the Düsseldorf School under the influence of Bernd and Hilla Becher in the 1970’s with its disciples Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth as well as the peripatetic Barbara Klemm, self-taught Michael Schmidt and the creative visionary, Wolfgang Tillmans , German photography sets definitive standards. A nod should also be made to the less well-known photographers of the former East Germany including but not limited to Arno Fischer, Sibylle Bergemann, and John Heartfield who carved a creative path in the face of significant obstacles,

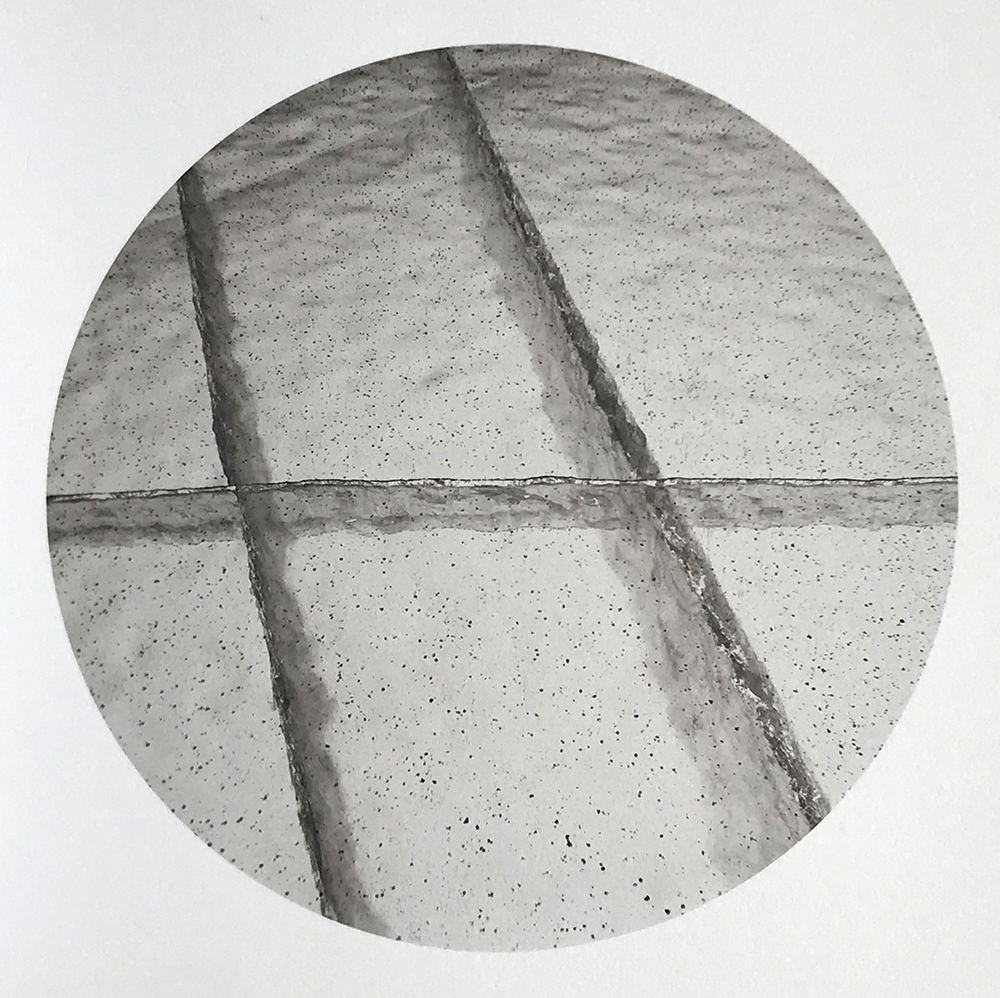

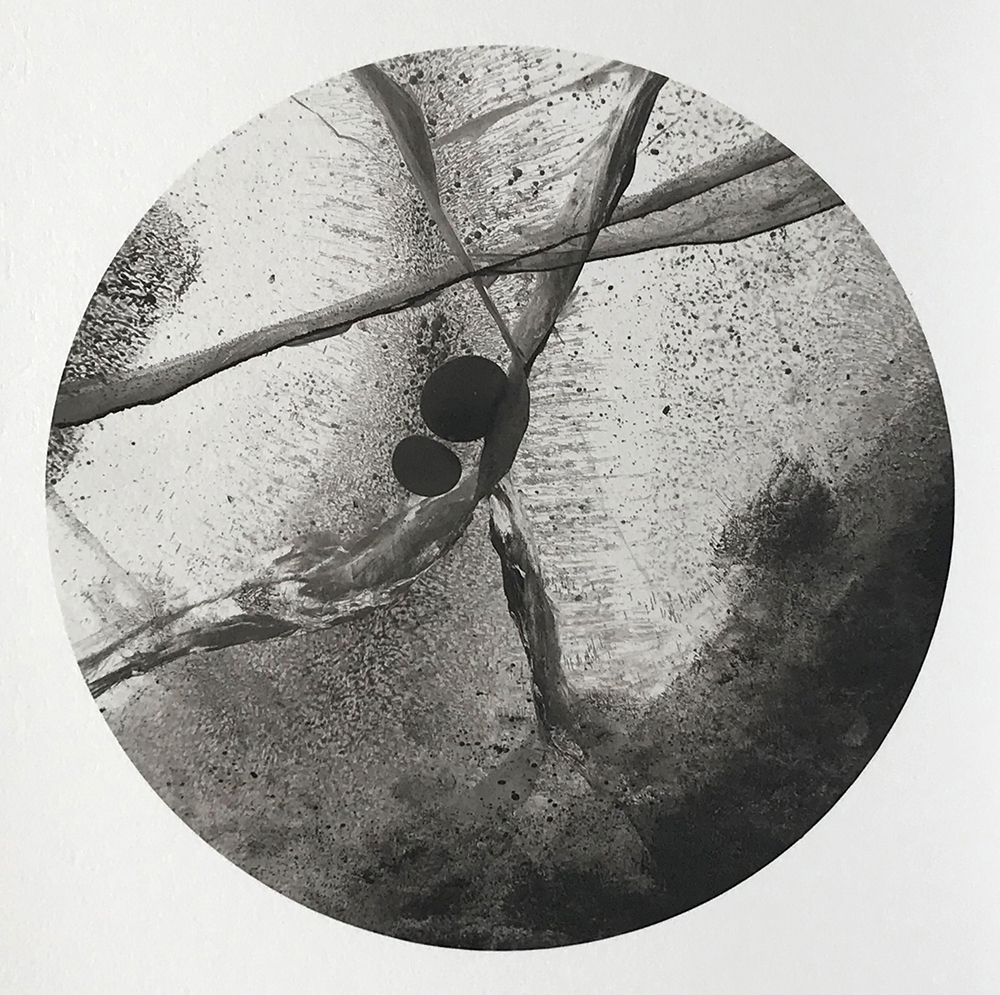

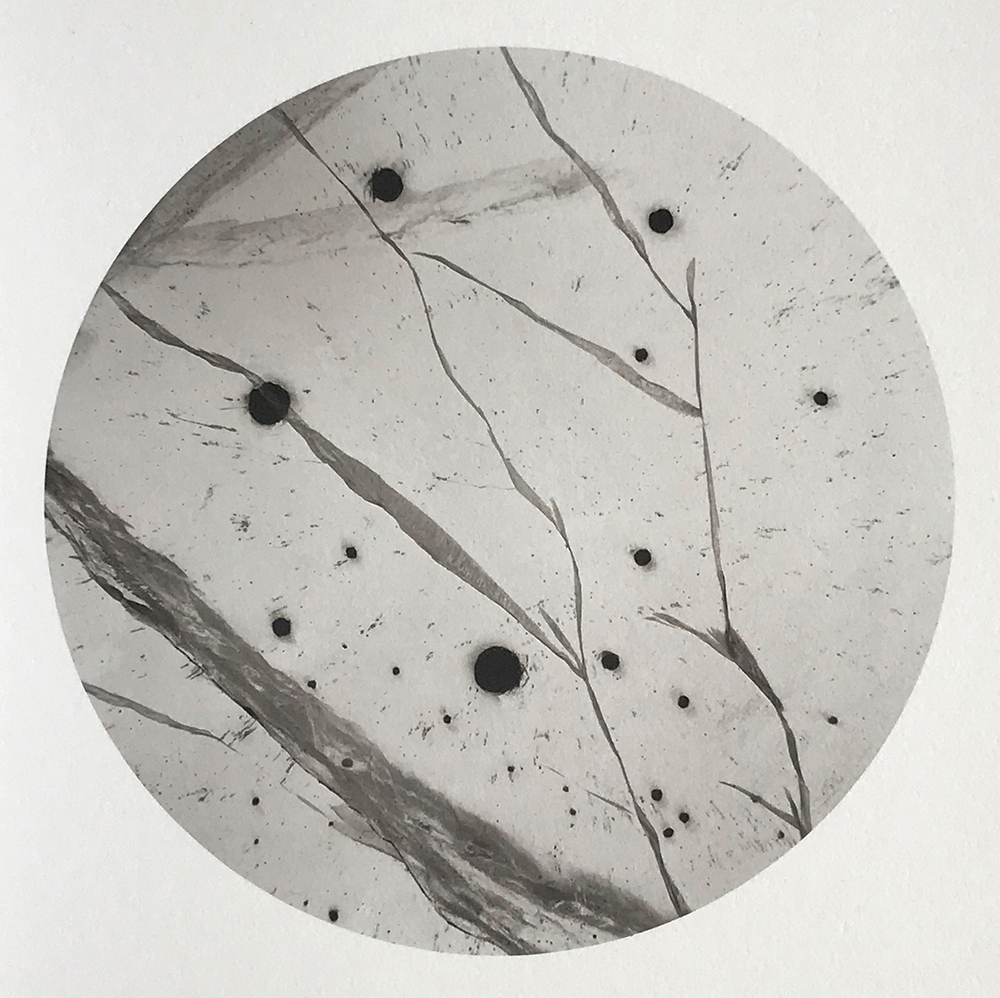

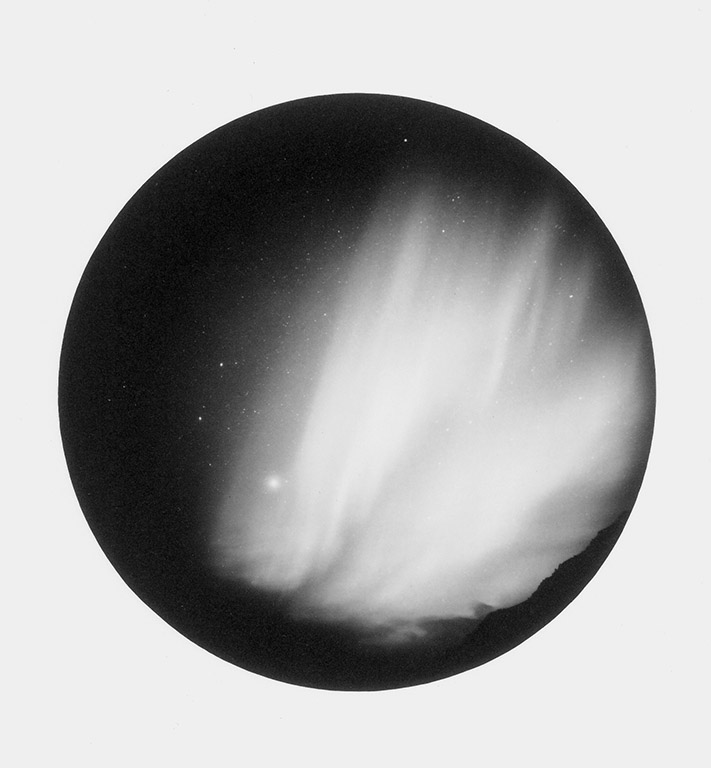

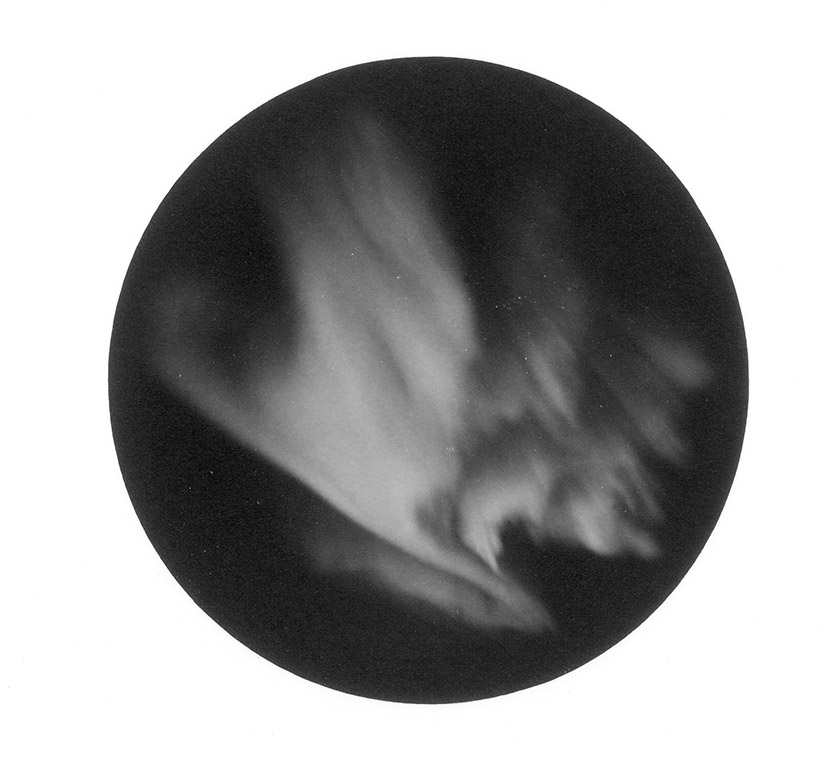

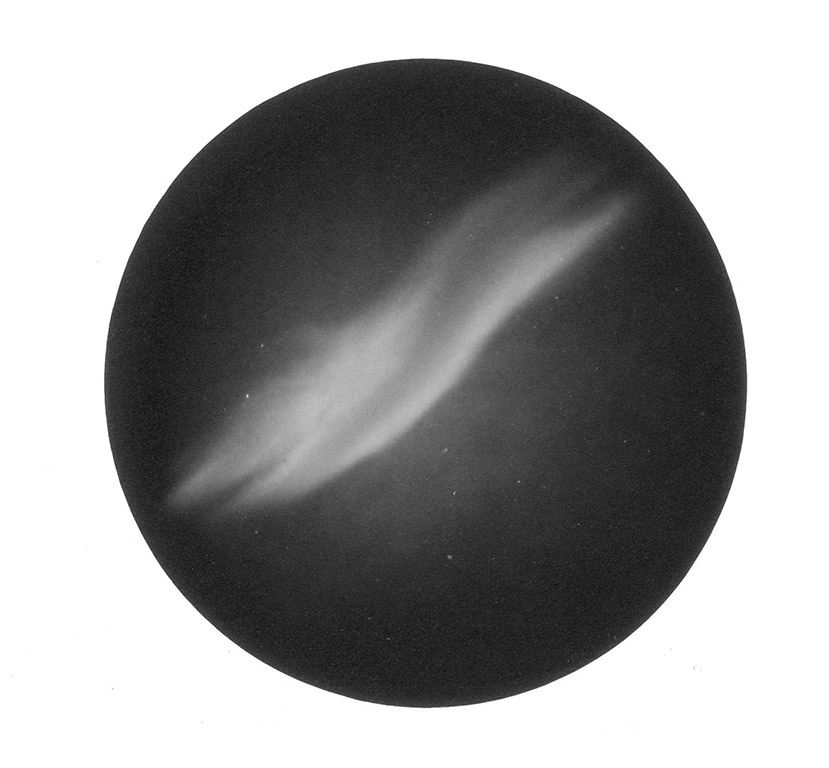

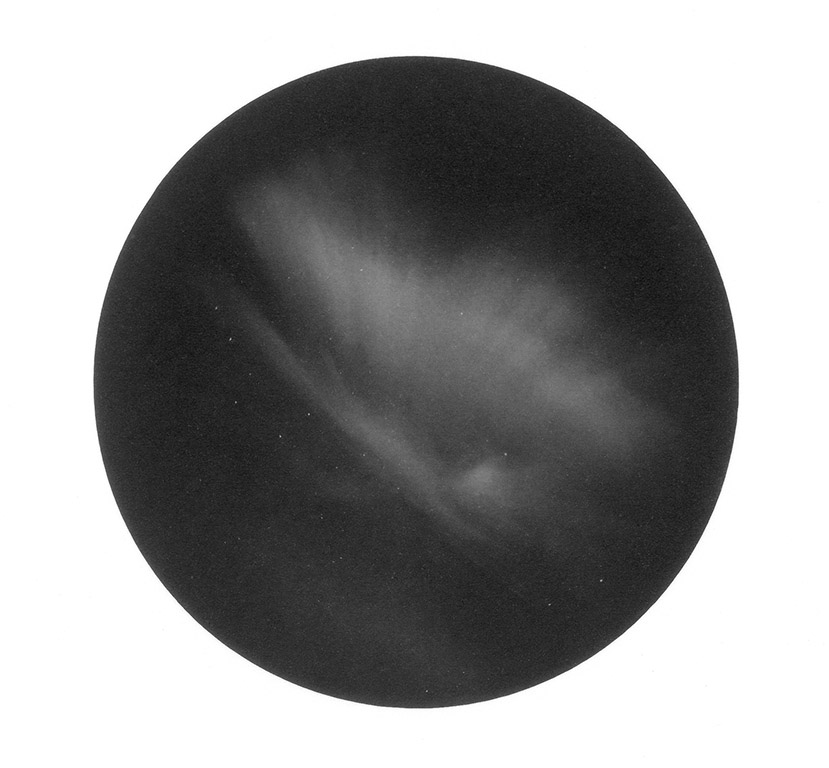

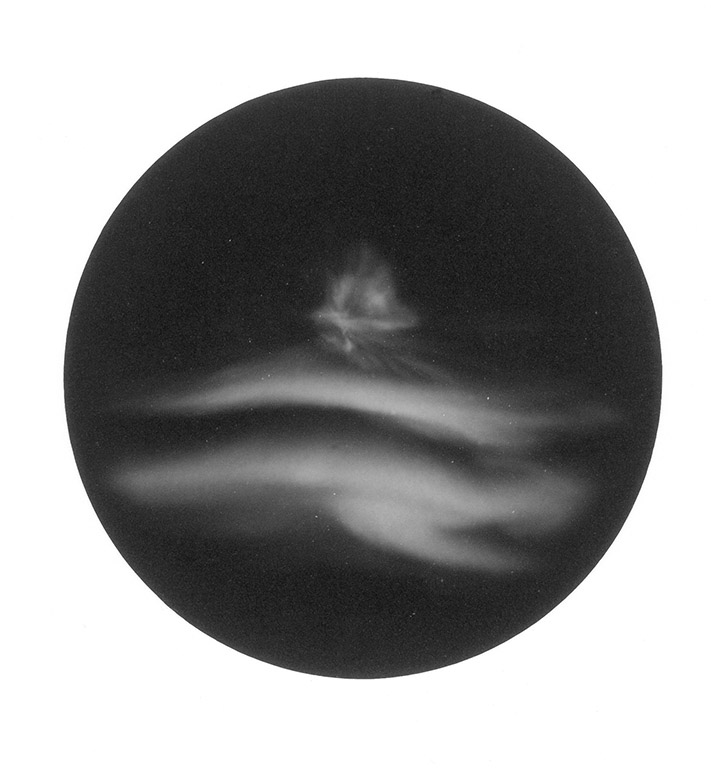

Jens Knigge toys with light at many levels and employs the added dimension of platinum printing to bring subtle details to the fore. His projects explore shadows, abstract shapes and angles that sometimes defy definition. This is particularly true with his project, Baikal, Sacred Sea, a minimalist view of a vast landscape that challenges the viewer to find the sacred in the sea. Knigge’s Northern Light exploration of the aurora borealis and the wintry landscapes of Northern Europe are mesmerizing in their minimalism. The aurora borealis emerges in a telescopic view of the heavens while the landscapes vary between the barely visible and invisible. All these images reap the benefit of the artist’s touch via the platinum/palladium alternative printing process which tends to enhance the mystery and depth of his subjects. Knigge also does graphic studio work with still lifes employing myriad objects in their utmost simplicity without sacrificing the slightest detail.

Knigge grew up in East Germany and studied to become an engineer. In 1987, he moved to Berlin where he lives and works today. Being self-educated in photography, he develops the contact prints of his analogue negatives as hand coated platinum-palladium prints. Knigge’s work is characteristic of extreme sensitivity to light and shadows, to shapes and textures: photography at the limits of abstraction.

His work has been shown widely including Paris Photo, Photo Basel, UNSEEN, Fotografie-Forum Aachen/Monschau, Museum Kunst der Westküste (Germany) and Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts (Japan). Knigge’s work is in the collections at Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts in Japan, General Consulate of Germany in New York, Art and Culture Center Monschau in Germany, among others. He has published two photobooks of his platinum prints, Contact Northern Light (2016) and Prima Materia (2020). He represented by Galerie Esther Woerdehoff in Paris and Johanna Breede Photokunst in Berlin.

Follow Jens Knigge on Instagram: @knigge_photography

Michael Honegger: Your project, Baikal, Sacred Sea is a series of almost microscopic views of the Sea of Baikal even using a round format that further enforces the viewer’s perception of peering through a microscope. What is the significance of your choice to portray a vast sea in miniature?

Jens Knigge: I am pleased when the works from the series Baikal – Sacred Sea give the impression of microphotographs. Because they aren’t. My goal was to create an abstraction in the multi-layered ice structures of the frozen Lake Baikal that does not completely lose its connection to the figurative and allows for a range of interpretations. The round format is intended to emphasize observation, as in early microscopic work, or astrophotography. While not spiritually inclined, I also use the circle format to draw attention to the importance of shamanism and Buddhism among the residents along the shores of Lake Baikal. By countering the tonal values in the finished print, I capture the idea of the underwater view, i.e. the supposed view from the underwater world against the light. I was very impressed by the importance of the ‘Sacred Sea’ in the everyday lives of the people who live there.

MH: What are the influences, if any, that you identify in your work that may define you in the context of German photographic tradition?

JK: It is difficult for me to attribute the influences on my work to a certain tradition. I suppose you might consider the serial work of some of my projects to the tradition of typologies.

MH: Your use of platinum/palladium printing for your images is pervasive and provides a level of detail that is rich yet subtle. What prompted you to choose this elegant alternative process consistently in your work?

JK: The platinum/palladium print runs like a red thread through my various series. Essentially, it will be because materiality is very important to me in my work. Collecting light with the film plate and developing it in the darkroom, then transferring this image to hand-coated platinum/palladium paper, all of this corresponds to my understanding of the balance between the artistic component in the sense of idea and composition, and the demanding manual work with paper.

MH: You originally grew up in East Germany and moved to Berlin in the late 1980’s. What impact did your upbringing have upon your development as a visual artist?

JK: It is difficult to answer this question. My early childhood education naturally influenced my development a lot. My parental home and my school education were not particularly artistic, apart from musical activities.

MH: Your projects vary widely in their subjects and photographic styles, yet the one consistency is the detail and use of platinum/palladium processing. How do you decide upon a particular project to pursue?

JK: In terms of visual language, I’m not particularly attracted to the opulent compositions. This is also the case when I appreciate art. Whether it’s Paul Outerbridge’s Saltine Box or Harry Callahan’s power lines in Detroit, I’m fascinated by these minimalist images, reduced to the absolute minimum, with a very graphic language. If both fit together for me, the idea and the composition of the picture and I already see this picture as a platinum print in my mind, then I can get started.

MH: Several of your projects have an implied focus upon environmental concerns including your images of Lake Baikal in Siberia and the northern Arctic regions where you have photographed. Is this a coincidence or intentional?

JK: Let’s say they focus on our relationship with nature. This is no coincidence but expresses my feelings. Whether in the recordings of the Aurora Borealis or the entire Northern Light series, the cosmic connections in our planetary system have such an immense influence and we encounter them everywhere. We all know that the solar winds deform our magnetic field and create this beautiful light, or that the tilt of the earth’s axis means that the sun does not appear in the wintry north. But it’s important for me to think about it.

MH: Since you are self-taught in the photographic medium what other photographers or artists have had an impact upon your vision?

JK: There are many artists whose work impresses me in different ways.

Be it in terms of visual language, artistic attitude or technology.

Vija Celmins with her minimalist drawings, and of course the two photographers mentioned above, inspire me with their reduced visual language.

Sticking to your own idea, regardless of the acceptance of the general public is most important. Prof. Gottfried Jäger impressed me very much with his generative photography. And, of course, as far as the overall work and the printing process are concerned, Irving Penn! For me Penn is a great artist and impressive person.

MH: What is next on the horizon for Jens Knigge?

I am currently working on a book project in which I combine two completely different series. It is also about getting closer to nature. On the one hand there are landscape shots, which for the first time are not based on my camera negatives, but on digital image files from Icelandic traffic surveillance cameras. In the studio, I brought these digital screenshots into the world of platinum prints in various digital and analogue steps. This created a very impressionistic impression. I then went on a road trip on these streets, which were monitored by the cameras, and photographed the scenery to the left and right. There are also portraits of the people who live there. All this with large and medium format analogue, but in color! I wanted to immerse myself in the world of the local people. I haven’t seen this world in platinum. The main idea is to look at the Icelandic landscape in winter, from two completely different perspectives. I hope it works!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026