Germany Week: JAKOB GANSLMEIER

This week Lenscratch will turn its sights upon the artistic output of German photographers who present a broad array of the personal, social, historical, and political influences of life in contemporary Germany. Germany’s contributions to the photographic realm are extensive from the earliest days of the genre. From August Sander’s People of the 20th Century, a portrait study of all strata of German society, to the Düsseldorf School under the influence of Bernd and Hilla Becher in the 1970’s with its disciples Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth as well as the peripatetic Barbara Klemm, self-taught Michael Schmidt and the creative visionary, Wolfgang Tillmans, German photography sets definitive standards. A nod should also be made to the less well-known photographers of the former East Germany including but not limited to Arno Fischer, Sibylle Bergemann, and John Heartfield who carved a creative path in the face of significant obstacles.

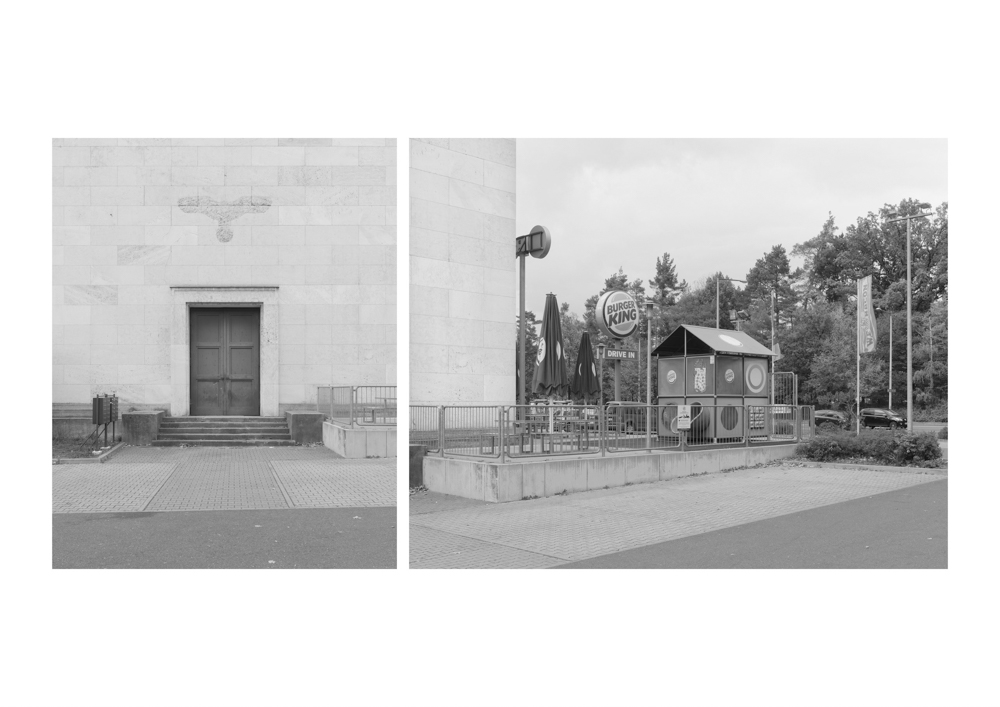

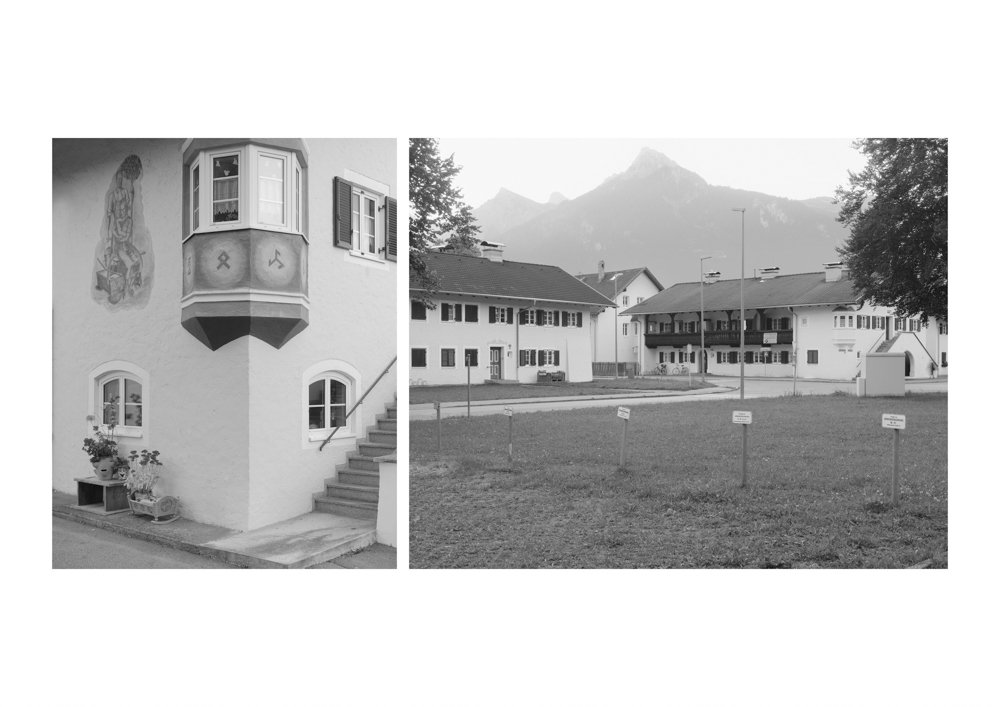

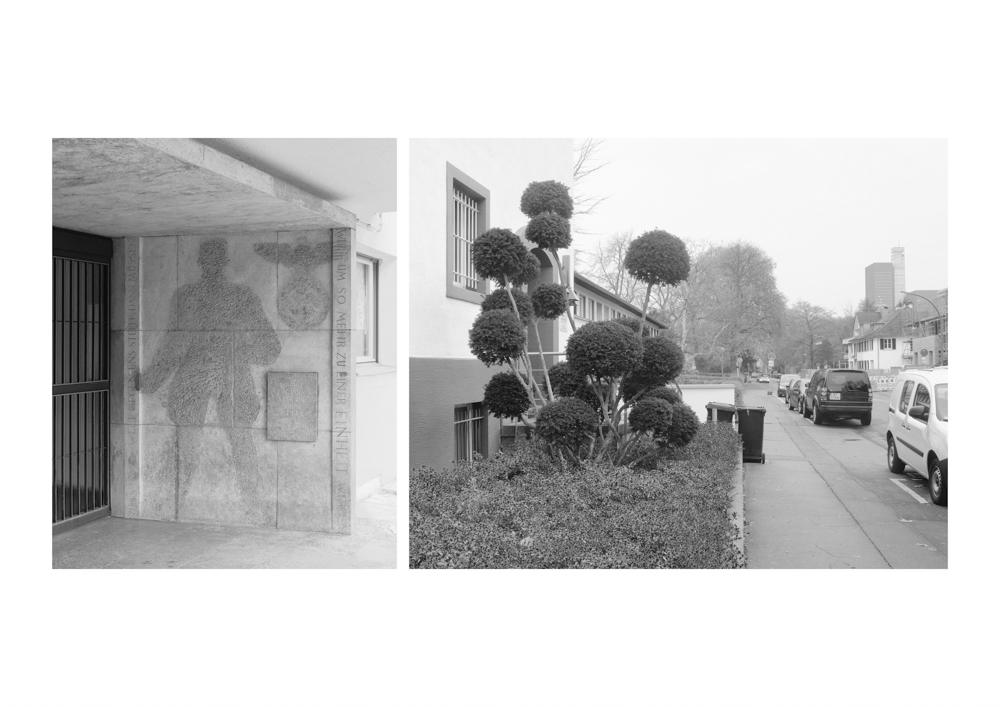

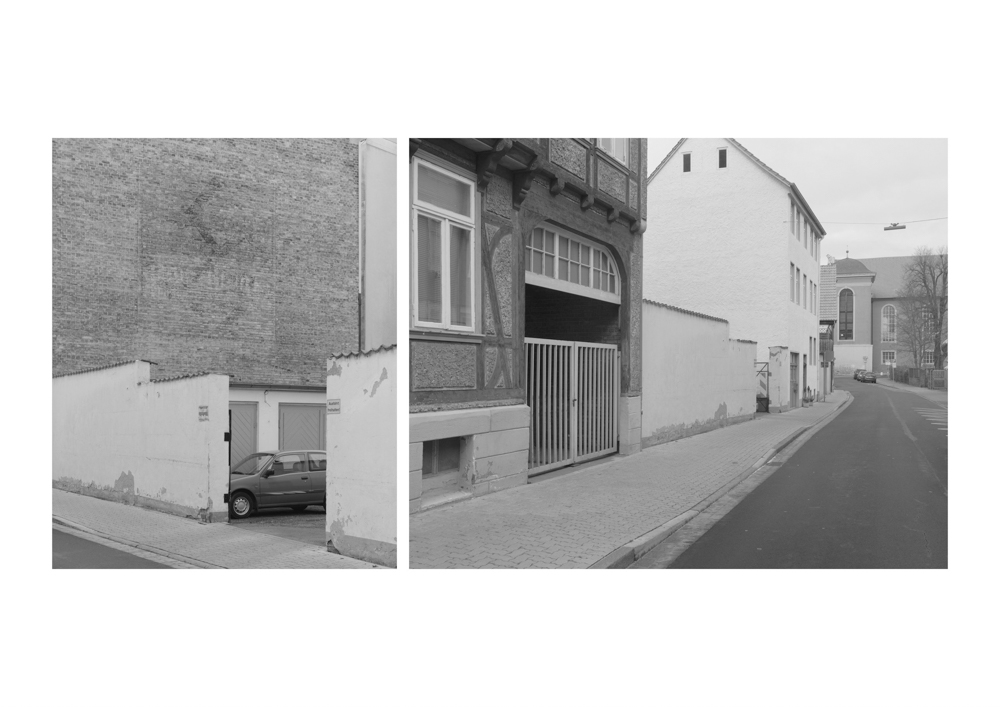

Perhaps the most directly political and socially engaged project that this week’s focus on German artists has uncovered is the striking and provocative work of Jakob Ganslmeier’s Haut, Stein (Skin, Stone). This documentary study juxtaposes stark color portraits of remorseful right-wing extremists who erase the tattooed symbols of their politics with black & white architectural landscapes depicting the still extant and blatant symbols of Nazi Germany on public buildings throughout Germany. Ganslmeier’s stark portraits confront the viewer directly with the fading artwork of the skin on torsos, backs, hands, arms, and legs. This theme reappears in the architectural landscapes only this time filled with faded Nazi swastikas still evident in public spaces in towns and villages of contemporary Germany and that have not been completely erased.

Jakob Ganslmeier is a photographer and visual artist based in Berlin and Den Haag. Growing up in Dachau, in proximity to the former concentration camp and nowadays a memorial center, he quickly developed an interest in socio-political topics. In his artistic practice he dismantles the visual representation of radical ideologies and offers counter-narratives through photography, video, and other visual media. His works have been exhibited internationally, among others at the Museum of Contemporary Art Kraków, Deichtorhallen Hamburg, the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Cottbus. He is the recipient of several awards and grants such as the European Photo Exhibition Award, the Lotto Foundation Young Talent ArtPrize, or the BBK Berlin grant.

Follow Jakob Ganslmeirer on Instagram: @jakob_ganslmeier

According to Ganslmeier’s artist statement, “the color photos focus on the documentation of the removal of – in some instances–extensive tattoos depicting right-wing symbols and signs. I capture the process as the physical inscriptions disappear, which up to this point, have been for years an expression of one’s identity and political ideology. To remove symbols so fused into the body is highly deliberate step for an ex-Neo-Nazi, because the elimination of these distinctive marks is an expensive, lengthy, and painful process. The process of individuals breaking away from the right extremist scene is captured in photographic portraits that trace the renunciation of an ideologically charged environment, both individual and communitarian via the removal of white supremacist tattoos.

The B/W photography shows historical Nazi symbols being integrated in architecture and therefore having a presence in the public space. Despite the so-called denazification, overpainting or other interventions, they are still visible and therefore part of the everyday in cities and the countryside. The photos of these architectures and their peculiar historical inscriptions are conceived as diptychs.”

Michael Honegger: What are the symbols or influences, if any, that you identify in your work that may define you in the context of German photographic tradition?

Jakob Ganslmeier: I certainly do see my work in the context of a German photographic tradition. I studied photography at three very different institutions — The Ostkreuzschule für Fotografie, FH Bielefeld, and The Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague. My time at the Ostkreuzschule was especially influential in terms of learning about the differences between the east and west German traditions. Perhaps most important was my relationship with Ludwig Rauch and Sibylle Fendt. Later on, at Bielefeld University, I studied under Katharina Bosse and learned to sharpen my project conceptually; making them more precise, while in The Hague, most emphasis was on the impact of making a photographic work, as well as a participatory approach to the medium. For that I am mostly indebted to Andrea Stultiens. Coming back to the question of tradition: I might sound old fashioned, but I believe in a humanist approach which is certainly not uniquely German, although many German photographers followed it.

MH: Your project Haut, Stein touches upon the conceptual and actual erasing one’s personal history in juxtaposition with the irony of how difficult it is to erase a nation’s historical symbolism. What gave you the idea to pursue this interesting contrast between the personal and the communal?

JG: While being in contact with individuals leaving the far-right extremist scene, photographing them in the process of laser removal or covering up their right-wing extremist tattoos, I had the opportunity to have many lengthy discussions. One of them told me that during his active time, he organized trips to ideologize younger members. They would go to places like the Wewelsburg, the infamous castle often related to Heinrich Himmler’s SS cult, to train each other and commemorate their Nazi heroes. These places are full of Third Reich symbology. I knew about many Nazi buildings and remaining symbology such as the Arno Breker statues at the Olympia stadium in Berlin or the swastikas on the Haus der Kunst in Munich but wasn’t fully aware of its scope. Many (sometimes de- nazified, sometimes not) symbols can still be found in the German and Austrian city landscapes.

I am not sure if I understand this as ironic. It is rather a well learned mechanism of looking the other way. Perhaps as someone who grew up in Dachau next to a former concentration camp I lack the distance, but what I asked myself during my research while producing this part of the work is how these symbols of power, the symbols of a certain ideology which killed over six million people, can be left untouched. Nazis positioned these symbols around to express an omnipresent power, and yet today there is not even a simple text board present at most of these places to contextualize them.

The parallel to the tattoos is that often the symbols are the same. Whether they are inscribed in architectural elements or human bodies doesn’t matter: swastikas, very often runes, and portraits of soldiers. In both cases, there has been an attempt of these symbols being removed or reworked, and yet sometimes they remain in their original forms.

MH: Many of your projects feature issues that are unexpected and surprising. One does not normally think of neo-Nazis having second thoughts about their political body art nor of contemporary German towns with subtle remnants of the Nazi era. Another project deals with PTSD among German soldiers. What inspired you to uncover these topics that are not exactly typical or traditional documentary pursuits?

JG: I work on long-term projects, which is rather common in the field of documentary photography. After my first studies, I wanted to become a documentary photographer and work for magazines. That never really worked out because printed media were already facing a crisis, and on the other hand magazines and newspapers, also very big ones, were often hesitant to show works such as Haut, Stein. Only a few printed it, however when it did happen, it was given enough space and the collaborations with editors and journalists tented to be close ones. In general, I feel that I never fully entered the German magazine world. I gradually shifted my focus towards exhibitions and installations in different contexts.

In Trigger in which I photographed Soldiers with PTSD, my starting point was again a question. How can I make the mental struggles of soldiers returning from Afghanistan visible? What both projects have in common is the fact that people often prefer to avoid any discussion on this topic. There was little interest in dealing with psychologically wounded soldiers and the problem of Neo-fascism. Same can be said for the German past in general. As long as it is consumed through the History Channel it is all fine, however when you try to position it in relation to current discourses, it becomes a different story. Both projects are highly uncomfortable.

MH: How did you discover the subjects for the “Haut” portion of the project and how did you get them to agree to pose for you given what they were experiencing in erasing their past? How did you uncover the architectural details from the Nazi era?

JG: The former Neo-Nazis I portrayed were part of the Exit-Germany programme. Exit is an NGO helping former right-extremists leave the scene. They have the necessary experience and expertise, which gave me the trust that the people I photographed were truly committed to stepping out. Of course, this went both ways as the individuals portrayed also had to trust me, which took a while. You must imagine that if you leave the scene, you (and very likely your family) are most going to be in serious danger, including death threats. Depending on how long you have been part of it and which group you belonged to, you might have to change your name, or at least leave your city and country. As you can imagine, many were not too keen on being photographed and exposed in such a way. One of them once said to me that he is taking part because he doesn’t want to see his life story repeated. That made a lot of sense to me. As for the architectural part, I made extensive of research on my own, collaborated with historians and spent some time on the road. In total, I visited over 50 German cities and towns.

MH: Your work frequently has political overtones? Do you feel that this helps or hinders the message that you are trying to convey?

JG: That is probably a question for the public to decide. It depends on the context and to what audience they are shown. I personally consider the topics I deal with to be political, and that certainly impacts the work. Still, I see the pictures as questions rather than political statements.

MH: How do you maintain the balance between irony and documentary narrative in your work? Your recent video work is particularly challenging in this regard.

JG: Poetry Is Out of Place which I did in collaboration with Ana Zibelnik and Dutch documentary producer Paradox, raises questions such as: why does the fascination with Nazi ideology keep resurfacing today? How easily is an ideological vision (re)constructed? Why are hateful messages so often disguised as images of hope? It consists of six video installations, some of which use irony to give the viewer the necessary distance to the challenging images that you see. In general, I don’t see documentary narratives as very closed, if they hold their ethical premises to their subjects and collaborators. Luckily, documentary narratives and methodologies are developing vastly and that enriches the field. Examples of this richness include the school of speculative documentary established by Max Pinckers and Michiel De Cleene or the influences of magical realism that we can see in the work of many photographers. In that sense using irony (and I am certainly not the first one) adds to the field of documentary narratives rather than excluding them.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Sirkhane DarkroomMarch 26th, 2024