Roció De Alba: Pobresito Artista Que Era Yo

I first met Rocio De Alba over Zoom for our interview a few weeks ago. It was a disaster of a morning on my end; I had recently moved and my internet wasn’t properly set up. As soon as I joined the call to start our interview, I lost connection and could not rejoin. I had to run to my car and drive somewhere with internet connection, panic and embarrassment racing through my veins as I feared I would be viewed as unprofessional. When I finally returned to the call, I was instead met with immediate kindness and understanding that became a recurring theme of my conversation with Rocio. Despite never meeting face to face prior to this and having only briefly communicated over email, it felt like there was an immediate connection between us. She was easy to talk to, and the longer we spoke, the more it felt as if we understood each other on an emotional level. Towards the end of our conversation, Rocio said, “When I read about you, I thought… I believe this is a good combo because I relate to her work and I think she might relate to mine. That’s when art speaks and forms community. When I can relate to you and you can relate to me and we don’t know each other.” This kindness clearly permeates her being as she opened herself up to me in a way I’m extremely thankful for.

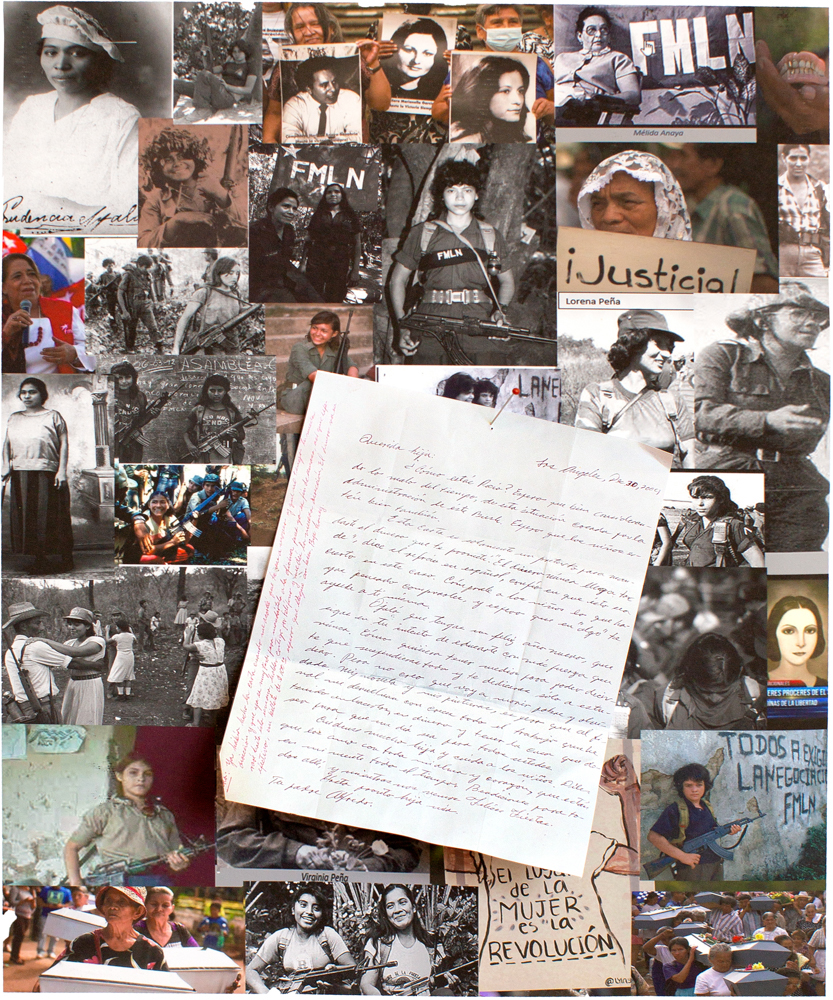

PROBECITO ARTISTA QUE ERA YO

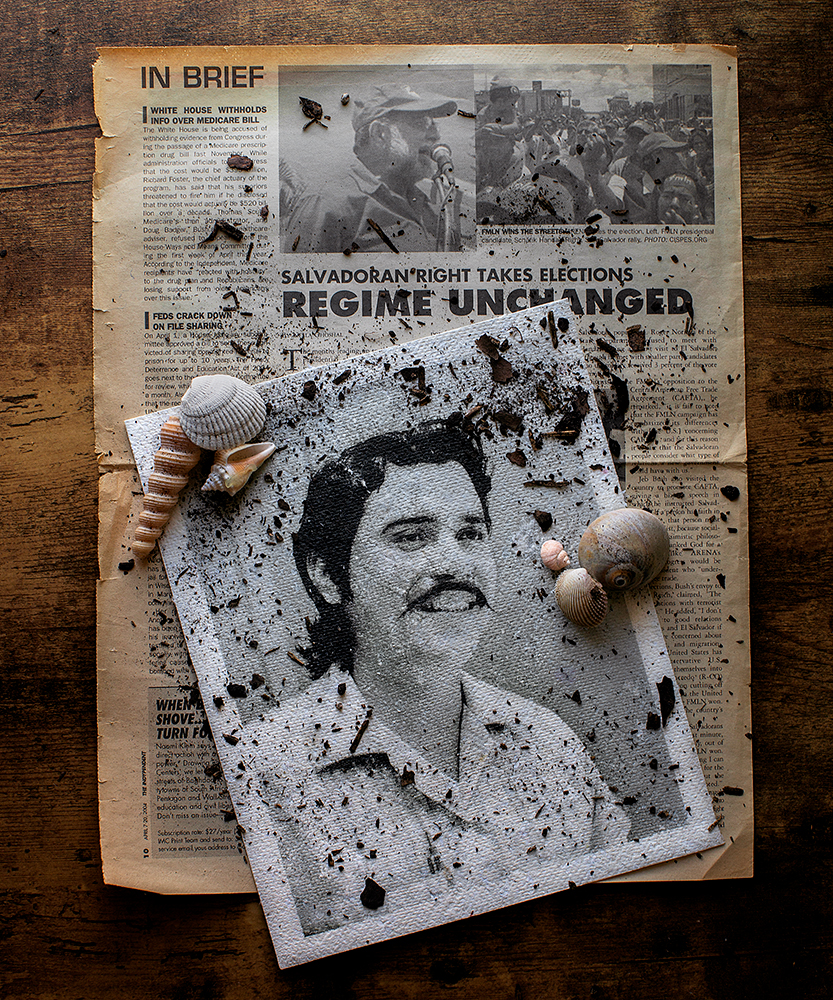

In this deeply personal series, I embark on a heartfelt journey to understand the complex relationship I had with my father. It encompasses an exploration of his profound influence on my artistic aspirations and the gradual deterioration of his mental health that commenced shortly after our migration to the United States. Due to my father’s political affiliations, we fled our beloved El Salvador as refugees, leaving behind my mother’s family, my father’s successful career as an artist, and a comfortable upper middle-class lifestyle.

After settling in California, we encountered financial difficulties that contributed to my father’s battle with alcoholism. This struggle became the catalyst for the abuse he inflicted on my mother, siblings, and me. Eventually my mother developed the courage to divorce my father and with time, he found solace in sobriety and rekindled his passion for painting -even though the recognition he sought remained elusive. Feeling lonely and destitute, he retired and returned to El Salvador, which settled as s democracy that ended the revolution. Unfortunately, within two years he passed away due to complications related to diabetes that were exacerbated by his relapse into alcohol after twenty-five years of sobriety.

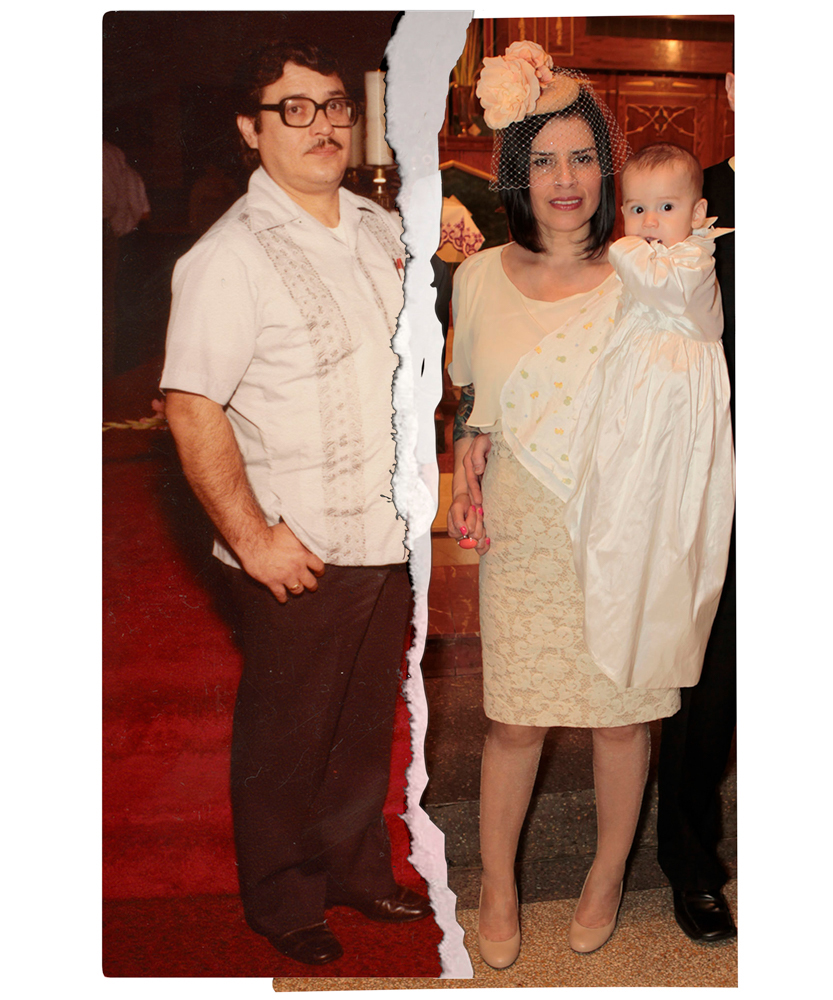

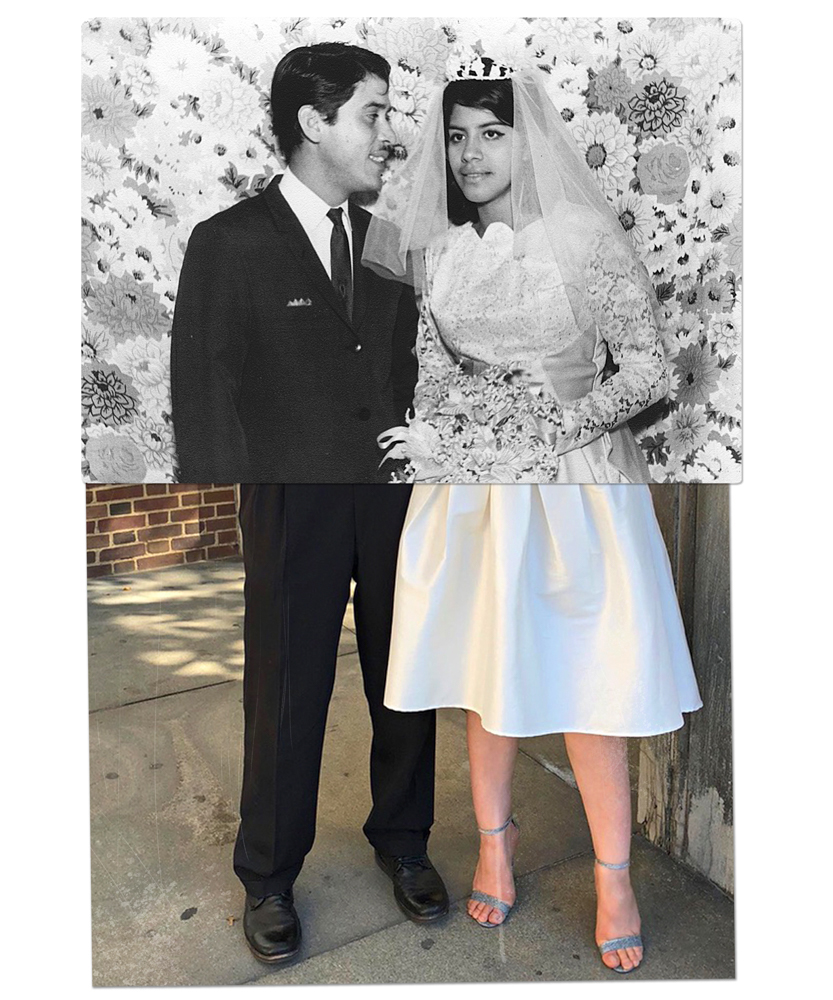

Initially, my mourning was superficial since my father and I had been estranged for ten years, burdened by unresolved emotions and distance. However, during the pandemic, I stumbled upon a collection of family photos that sparked a profound awakening within me. With the use of collage, superimposed images, and textual elements, my aim is to conceptually reconstruct the adverse narrative I once held of my father. Employing various multimedia techniques, I purposefully depict him as an ethereal figure—a beacon of guidance, support, trust, and companionship. As this series unfolds, it invokes a transformative journey of reconciliation, urging me to confront the intricate complexities inherent in familial bonds, unearthing long-buried memories, and ultimately discovering solace through the profound capacity of forgiveness.

Rocio last spoke to Lenscratch in 2016. Since then, she has experienced life changes. But, at the same time, she said, “I’m making art and enjoying it for the first time ever… And you know what, even as I’m saying it out loud, I’m thinking inside, ‘Oh my god, that is so true.’ For the first time ever since I ever began the idea of making art, I’m enjoying it. And I think I finally found my, I guess you could say voice. I really feel that.”

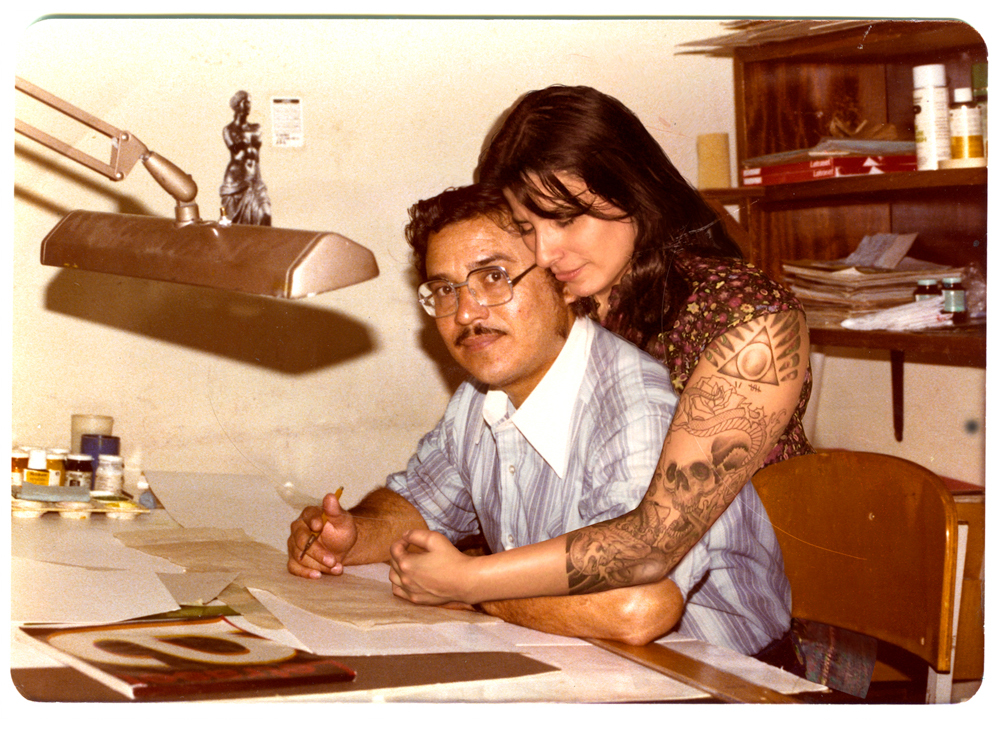

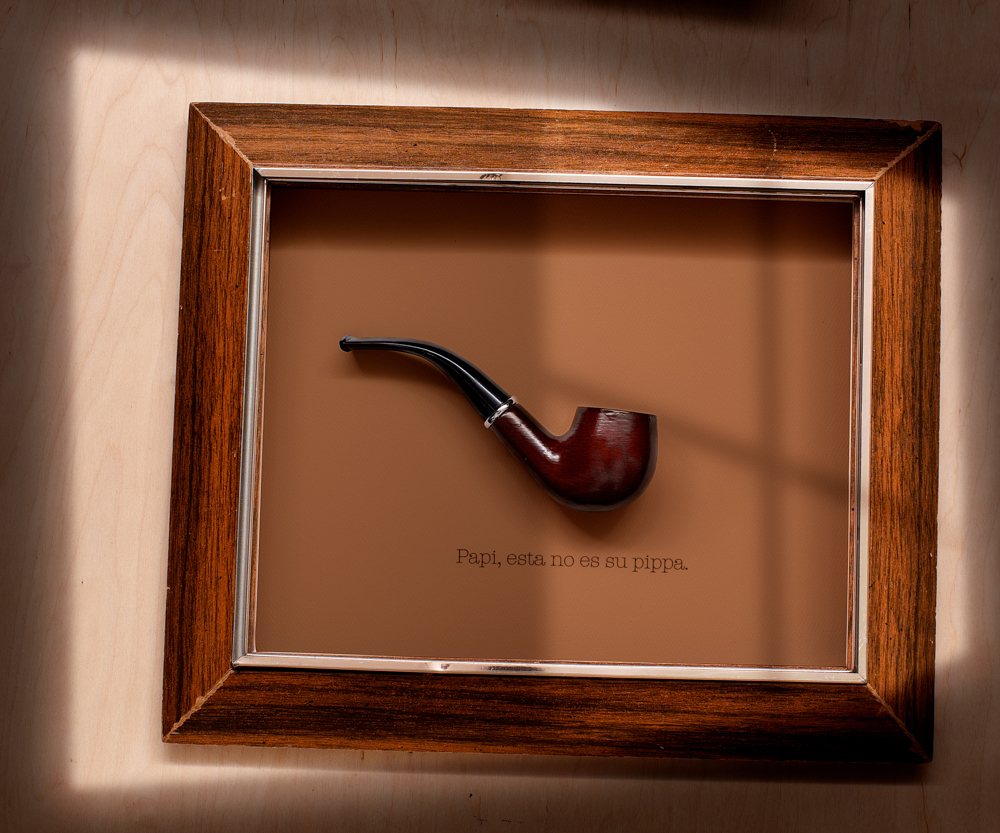

In particular, she has recently been working on a body of work called Probecito Artista Que Era Yo exploring her relationship to her father after his passing. This title comes from a book of poetry by a famous poet in her country named Roque Dalton. He was a guerrilla sympathizer of the Salvadoran Revolution that lasted over ten years. His book of poetry was entitled Probecito Poeta Que Era Yo, which means Poor Poet That I Was in English. It’s based around the concept of the poor little poet or artist who cannot get recognition and dies impoverished and unknown. The book was brought to her attention by her brother. Her father was a painter and graphic designer, and growing up in her country, her family lived a humble yet upper middle class lifestyle. Speaking about her childhood, she said, “So my father was one of those people that was very fascinating, very narcissistic, but yet very determined… And so I learned a lot from him with regards to art. And he was very intelligent about it, the way he spoke about it. And that’s really where I learned that art has a language. He painted… And he used us as subjects… and I learned that there was a magic in storytelling…”

In the 80s, however, the Salvadoran Civil War came, and her family was forced to escape as refugees as a result of her father’s political affiliations. Unfortunately, this move would prove difficult as the family had to leave their middle class lifestyle as well as their extended family. Her father was determined to be an artist, but he had to work as a gas station attendant due to financial difficulties. He had dealt with alcoholism in the past, being inspired to stop drinking after the birth of his children, but he relapsed. With time, he found solace in sobriety and rekindled his love of painting (even if recognition still remained out of his grasp), but, unfortunately, his struggle with his addiction was his undoing as he passed away.

At the time of his passing, Rocio had been estranged from him for ten years, thus leading to a superficial mourning period. During the pandemic, however, she began going through her personal family photographs and realized how many there were of her father and the profound feelings they brought up in her. Speaking on this, she said, “And I think that that’s the power of images… There is a true power in the emotional attachment that photography can create in our subconscious. Sometimes I felt as I was looking through the photos, there was a photograph I didn’t remember we had, and I would recall what a wonderful time that was, or what a horrible time that was. And how do you convey that feeling good versus a traumatic feeling? So, you know, one of my inspirations was, ‘Okay, I know what it was to live with my father and have horrible traumatic experiences… But there were good times, right?’ And I thought, ‘I have to rewrite the narrative…’”

Rocio’s work has dealt with addiction before, but never in this capacity. For her, like many of us, art has been a way for her to understand her emotional traumas. In the case of this project, these particular traumas stem from a deeply personal place, a place she has only been coming to understand herself as she creates these images.

One image in particular, “Choose Your Weapon,” deals with Rocio’s memories of her father trying to teach her to paint. “…it was his dream to have a prodigy artist in the family… he sat me down, and I was accustomed to having these large canvases in the living room, and the smell of oil paint was just wonderful to me. And so I would stand behind him and watch, and one day, he sat me down and said, ‘Here’s a canvas. Here’s a pencil. Draw.’ I don’t even remember what I drew, but he was not happy. He took those big paintbrushes, they’re humongous, and he whacked me on the knuckles. And he said, ‘No, erase it,’ and I erased it, and I did something else. ‘No, do it again.’ Tears are dropping down. He said, ‘You know what? Put that down and get out.’ And so I swore I would never paint…”

The paintbrushes hitting her fingers are a deeply visceral memory, and they were the starting point of this project. She saw those brushes as a way to confront her father, and so she went and bought some large brushes to photograph. While obviously a deeply traumatic memory, it’s also fascinating to hear the small little details that are remembered: the size of the brushes and canvas, the smell of the paint. And ultimately, they brought to mind good memories: the magic of his painting as well as her sense of pride having an artist for a father.

Before this project began, Rocio said she had been determined to not be like her father; it felt like the worst thing she could be. She described her father as one of those characters you know but don’t understand. This project helped her to better understand him, and because of this, she felt her father deserved to be forgiven. She also began to see how much his work had influenced her own, even without her realizing. And she realized perhaps that wasn’t a bad thing.

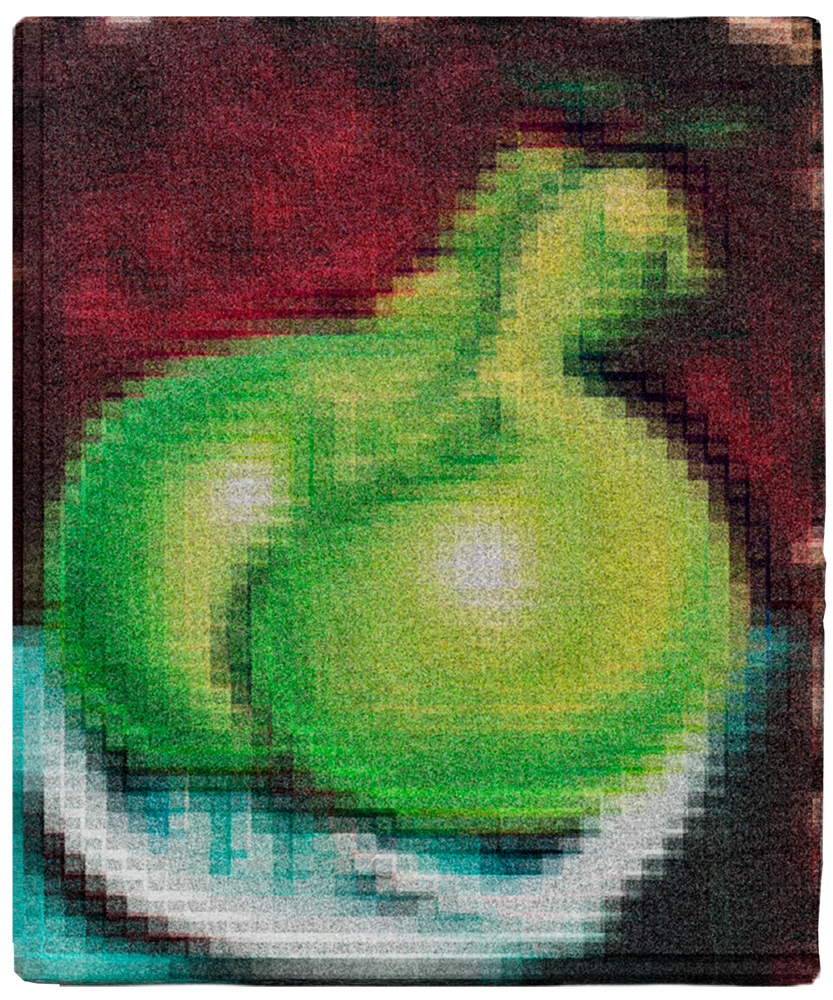

“There were so many images that I had created. For instance, there’s another photograph I called ‘Ode To Our Mad Men’ which is me, covered in butterflies with a background in roses. Well, I showed that image to my mother. And that image was inspired by one of my dad’s paintings that was hanging in the living room. In that painting was this man, this very bloated, deceased person who had been dead for so long, and on top of the person were butterflies. So when my mother saw my image, I said to her, you know, this is an ode to dad. And she said, ‘Well, you know, that painting your dad made as a gesture to his father.’ So I was just blown away, I had no idea that the butterfly image that I had made of myself, inspired by my father’s butterfly image, was inspired or done for his father. So the project kind of grew from there, there were so many parallels. And, you know, the more that I started to look through the photos of his paintings, the more parallels in our style that I saw, the more the project just kept coming…I had vowed to not be like my father, but yet we were so alike…’

Through this project, she was able to get to know her father in a way she couldn’t before. She could see him outside of his addiction for everything else he was: a revolutionary, an artist, an intellectual, a father whose hugs she missed; she could see him as a human being, flaws and all, who, ultimately, loved her as best as he could. And through this, she could mourn his loss more fully.

“As the process went on with the images. I thought, this is really feeling like me, you know, it’s really coming through, and I spent a lot of nights mourning him after that. When he initially passed away, I just sort of thought, ‘Okay, well, that’s too bad.’ And then it wasn’t until I started to do the images that I really had to stop for a little bit and let it out. And I cried. And the more I did that, the more I began to dream about him, and he would come to my dreams and [it was] very cathartic… And I knew I was on the right track. So the end result right now is something that I’m really happy with.”

She was also able to process her traumas related to her childhood and find her own artistic voice. She said, “I feel that I am just starting to understand my voice. I know it sounds corny as shit, but now I just want to roar. And I want to keep going. I found a new love for the medium, I found a new love for my father, I found a new respect for myself, and I believe that I am an artist.”

The work is still in progress, but this iteration of it is painfully and beautifully honest. It can be so easy, especially when you’ve been traumatized by an experience, to view things as black and white, all good or all bad. Yet very little in life is this cut and dry, and Rocio’s work in this project is a deeply humbling reminder of this fact. Staying distant from the loss of her father may have made things easier; in that way, he could stay in her mind as that man who hit her knuckles with brushes. Confronting him, delving deeply into her memory and recognizing him as the man who hit her knuckles but also as the man who informed so much of who she became, who she once felt proud to call her father, is much more difficult, and also, incredibly brave. Rocio choosing to take us along on this journey with her, holding our hand as we step into memories and bonds long-buried, showing us what it means to understand and forgive those who have hurt us is an incredible act of kindness both for herself and the viewer. And I consider myself incredibly lucky to have had her as a personal guide during this experience.

Rocio de Alba is a Salvadoran conceptual documentary artist based in Queens, New York. She earned a BFA in Photography from The School of Visual Arts. Rocio is an award-winning self-published book designer and has taught photography in many fine art institutions. She has won several prestigious grants from The Queens Council on the Arts -with public funding from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs; and she received a scholarship from the New York Foundation for The Arts (NYFA). Rocio was a recipient of The Center for Photography at Woodstock’s 2018 “Artists in Residency Program.” Her projects have been showcased internationally including exhibitions, features, publications and screenings, such as the Month of Photography Los Angeles‘ (MOPLA) Projekt. Rocio’s series have been featured and published on CNN Photos, The New York Times, PDN, L’Oeil de la Photographie, Lenscratch, and The Hand magazine. Selections of Rocio’s group exhibitions include Blue Sky Gallery in Oregon, Colorado Photographic Art Center, Vermont Center of Photography, Candela Gallery + Books, Foley Gallery, The Camera Club of New York, and Flowers Gallery. In 2017 Rocio’s series “She Who Found Grace” was shortlisted for the Kolga Photo Festival in Tbilisi. Her handmade self-published artist photo book, documenting her nine-year-old step-son entitled “Miracle Baby,” was part of an exhibition at the Elder Museum in Nebraska. The monograph then earned a finalist position at the Festival Documental in Barcelona. And on April 2017, it was selected into the INFOCUS Exhibition of Self-Published Photo books and displayed at the Phoenix Art Museum. In addition, the book joined a group exhibition at Fall Line Press in Atlanta. Rocio’s first solo show featuring her series “Honor Thy Mother,” traveled extensively commencing with a show at The Griffin Museum of Photography, curated by Executive Director Paula Tognarelli. The project moved-on to The Providence Center for Photographic Arts in Rhode Island, followed by an exhibition at China’s Yixian International Photography Festival.

Follow Rocio on Instagram: @rocio_de_alba

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Larissa ArazMarch 28th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024

-

Mexican Week: Cannon BernáldezFebruary 6th, 2024

-

Erika Kapin: Mom and MeJanuary 19th, 2024