Isolationism in Photography: Luis Lazo: All That You Leave

What does it mean to be alone? To be isolated from the people and things we hold dearest? Since the pandemic, it seems like we all have an answer to this very question. Some people embraced the mandatory isolation while others struggled being forced to be apart from their loved ones. This week will feature photographers who captured moments they felt most alone and the ways this isolation expressed itself in their lives.

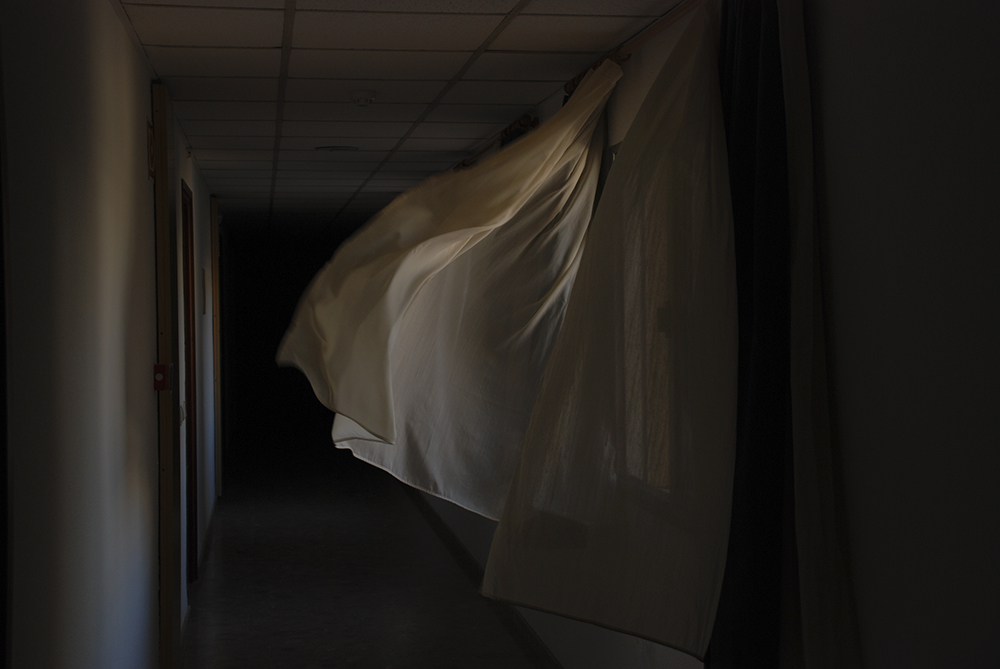

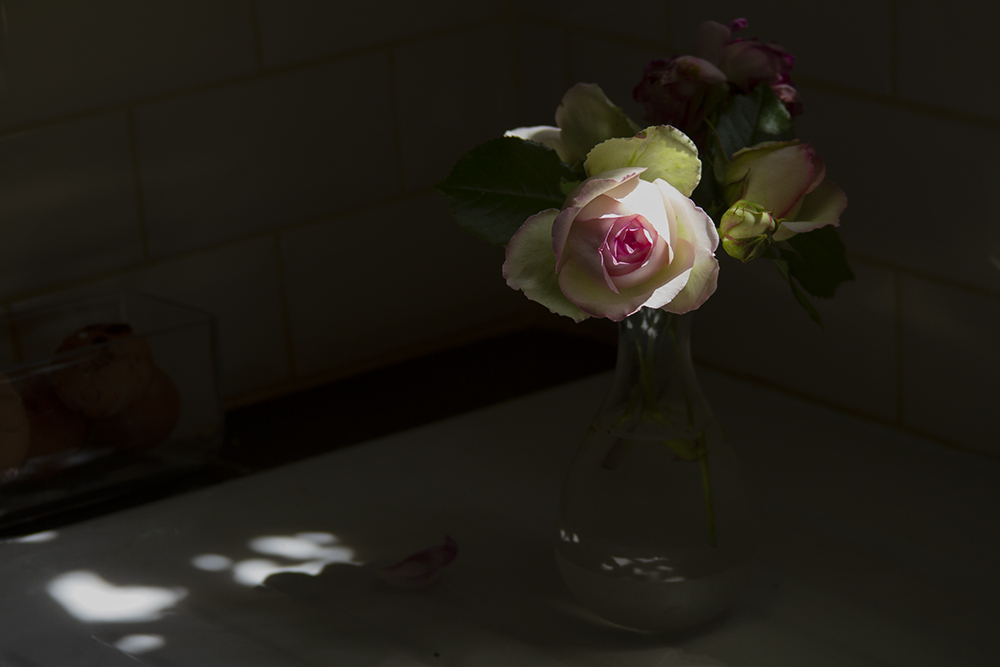

For Luis Lazo, loneliness came in the form of moving from place to place — picking up his life and relocating somewhere new. In his project, All That You Leave, Lazo captures small moments of his life at home, soon to be left behind. Deeply intimate and powerful, Lazo’s images encourage the reflection of one’s most precious memories and the everyday moments we take for granted.

Luis Lazo was born in Chile but grew up in England and lived in France before relocating to the U.S. He is currently in the process of relocating to Spain.

Lazo studied Art History and Photography at Bournville School of Art, before gaining a first class Honor’s Degree is Visual Communication from the University of Wolverhampton, UK.

He worked as a stills photographer on feature films as well as a portrait photographer for publications such as Harpers & Queens, The Telegraphy, and Premier Magazine. He also photographed fashion for magazines including British GQ, Twill in Paris, and SO-IN in Japan.

Lazo has had solo and group exhibitions in England, France, Holland, Italy, and the U.S. He was awarded Viewbook Photostory’s First Prize in conceptual category. He has self published and co-published four books.

Follow Luis Lazo on Instagram: @luislazophoto

All That You Leave

My work interweaves personal memories, landscapes, and portraits to reveal stories of shared experiences in a reflective and hopefully connecting manner.

Primarily concerned with the fragility of memory, my main aim is to engage and record the silent nature of fleeting moments where everything is stripped away, only the simple and essential elements remain.

I was born in Chile and when I was about six or seven there was a military coup there.

Over the following weeks there were internments, curfews, and disappearances. As my mother had been politically active she felt that it was too dangerous for us to remain there and so we were forced to leave.

I didn’t have time to prepare myself for this change. I wasn’t able to tell anyone, not school friends or neighbors, anyone, for fear of being denounced to the authorities. In fact, it felt like I had just disappeared, one day we were there, the next we were gone. I guess that in many ways I felt like I had lost my identity.

I think that the void created by these events eventually came to be explored in many of the projects that I later produced.

Following that experience, small, fleeting moments became fundamentally important to me as I attempted to hold on to them.

However, memories, like photographs, are selective and our inability to physically capture a memory means that we can only capture a fleeting representation of it. Whether painful or joyous, it’s ephemeral presence stays with us.

This series essentially began when I was preparing to leave France and move to the U.S. I attempted to capture images that might work as triggers, moments that might encapsulate something of the experience of living there.

The title suggests not only the remnants of ourselves that we leave behind, but also the people and experiences.

In essence, some small record of our existence. -Luis Lazo

Kassandra Eller: To start off I would love to discuss how your photographic journey began. What made you want to pursue photography?

Luis Lazo: In many ways my journey into photography felt like it was both by chance and inevitable.

Having left school with very little in the way of qualifications at the age of 15. I began working various jobs, including at one point, training as a mechanic by day and a hairdresser in the evenings, both were disastrous ventures.

Then a friend and fellow trainee who was into body building, bought a camera to record his progress and asked me to take some pictures. I had no clue what I was doing but somehow I immediately I felt like I had found something, a way to express myself, to communicate.

I eventually bought my own camera and began shooting everything around me. It was learning to see properly. Suddenly everything had potential, portraits, cityscapes, still lives.

The fact that an object or a person was framed within the viewfinder of my camera gave it some kind of validity, gave it importance.

At the same time, and in a very simple way, I was learning how to see light, to see what it actually does. How it reveals and sculpts, not in a scientific sense but in a much more abstract and natural way.

It took another couple of years before I plucked up the courage to put together a basic portfolio, while I was working as an assistant in a psychiatric hospital, and apply to art school.

Art school was so stimulating and creative, that I was sure that this was finally something that I really wanted to pursue.

KE: You state that All That You Leave began when you were preparing to leave France.

How long did this project take you and when did you know it was a completed project?

LL: In hindsight, I think that the project lasted approximately a year, more or less the time that it took for us to organize our departure from France to the US.

It was never actually began as a specific project, so in many ways it was an open ended idea.

They weren’t images that I was originally planning to share. They were simply moments that I was trying to capture as naturally as possible prior to our departure. A reflection of a place or thing that I would most likely never go back to or simply as evidence of a moment.

It only really came together and to an end when I entered the images into an international photography competition and it won first prize. The series was subsequently exhibited at the Kahmann Gallery in Amsterdam and a small book was produced.

Though I continued to make other images for this series, the project felt like it was essentially done once it was ‘out there’ and we had moved.

KE: The way you use light and shadow in these images emphasizes the feelings of a dark haze and loneliness as I look at your work. Are there any specific techniques or tricks you use to capture these haunting images?

LL: I didn’t intend for the images to feel dark or lonely, but they are quite introspective.

Perhaps part of the reason that the images may seem lonely is because the dialogue was essentially taking place within myself, inside my head.

I didn’t employ any specific techniques as such, but the use of light and shadow together with the limited colour palate, seemed to leave certain things to the imagination while also alluding to life outside the frame. Depicting the evidence of human life without always showing the form directly.

As the title suggest, All That You Leave is not only about a physical departure but also about traces of ourselves that remain.

KE: Each photo contains a sense of stillness. Did you create these compositions or choose to document life as it was happening?

LL: Every image is captured as it happened, I am not art directing. My fascination comes from the act of looking and observing rather than creating an imagined scene.

I guess this may go back to my arrival in England as a child and didn’t speak a word of English.

When you don’t speak the language, visual clues, gestures and tone become really important in trying to read or understand a person and a culture.

Likewise, I try to load my images with some of those subtle visual clues.

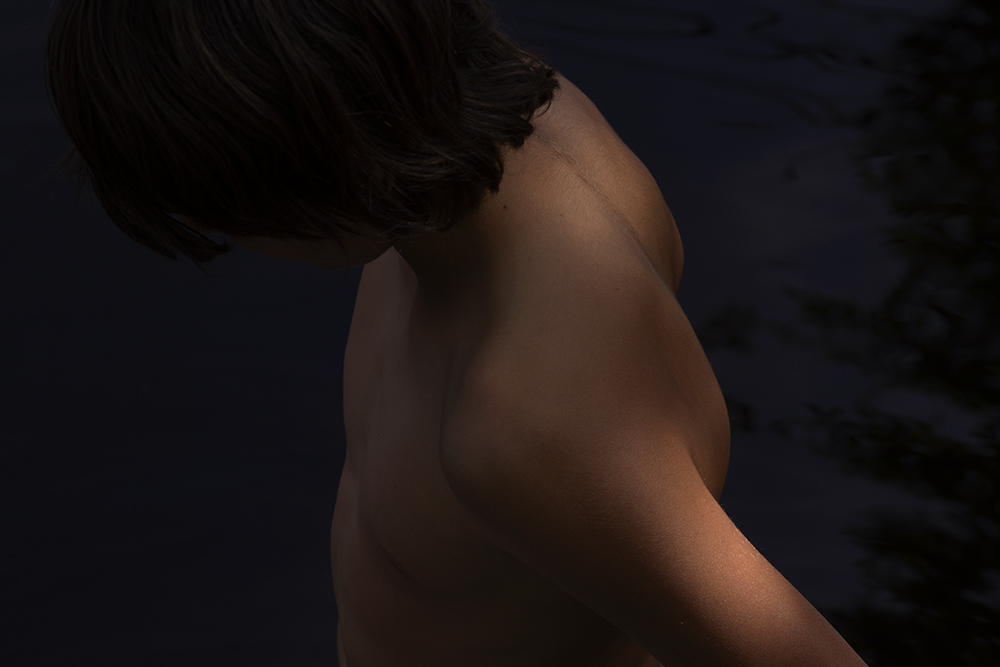

KE: Many of the photos in this project focus on an object or scene rather than a human subject, however, there are two people who are featured in some of the photos. Why did you choose to include these two subjects specifically?

LL: Well, the two people featured in this series are my wife and my son, the two constants in my life. My closest and most intimate human connection. They are mainly featured in close ups to accentuate that intimacy.

KE: I love how in your statement you say “aim to engage and record the silent nature of fleeting moments where everything is stripped away.” Could you expand more on this idea and how you go about photographing these fleeting moments?

LL: The most important thing for me is to be in and react to the moment. Despite the fact that I have a camera to my eye, I am absorbing everything in the scene and the moment. Taking the picture is second nature to me, an extension and enhancement of that moment.

I think that my work and especially this series is based on the idea that everything is important and much like a Murakami short story, it sets a mood, it gives you clues, but ultimately the images remain ambiguous and open to personal interpretation

KE: Many times the projects I take on become a way to process my emotions. It seems as though All That You Leave may have done this for you. Did this project become a therapeutic way of understanding and processing the emotions of isolation and loneliness you felt as you were preparing to move?

LL: Pretty much every project that I take on is in some way therapeutic, whether by allowing me to process certain events or by allowing me to investigate unresolved emotions.

I was born in Chile and when I was about seven there was a military coup there.

Over the following weeks there were internments, curfews and disappearances. As my mother had been politically active she felt that it was too dangerous for us to remain there and so we were forced to leave.

I didn’t have time to prepare myself for this change, I wasn’t able to tell anyone, not school friends or neighbors, for fear of being reported to the authorities. In fact, it felt like I had just disappeared, one day we were there, the next we were gone. I guess that in many ways I felt like I had lost my identity.

I think that the void created by these events eventually came to be explored in many of the photography projects that I later produced.

Many, inevitably deal with the idea of trying to establish some kind of connection. This might be with myself, my past, my environment or people in my life .

KE: Is there anything you are currently working on?

LL: I usually work on a couple of projects at a time, I feel that this helps to keep my thoughts and ideas fresh while also allowing for new and unexpected connections that may develop as the projects progress.

I am primarily looking to expand on the series that I recently exhibited at Sotheby’s in Amsterdam in collaboration with The Gallery Club. A series of familiar yet symbolic images and moments from daily life. Images that when removed from their conventional and original contexts create new dialogues when juxtaposed.

I am also working on a book that is currently at the final editing stage.

The book is essentially about an inevitable passage of time. Sometimes almost indistinguishable, but in constant flux.

It interweaves black and white and color photographs of both day-to-day encounters and staged moments. Bodies and flowers, rocks, birds and landscapes, each image hinting at different stories.

Several motif re appear and influence previous perceptions of the image. However when edited, overlapped or juxtaposed they reveal a more singular and personal narrative.

Interspersed Haiku poems, allows for reflection beyond each image and into life in general.

Haiku is a Japanese poetry form. It uses just a few words to capture a moment and create a picture in the reader’s mind.

Traditionally, they depicts a tiny moment in time and much like these images, it is like a tiny window into a scene much larger than itself.

I have collaborated with Aaron Lazo, a music producer who has created a mesmerizing soundscape to accompany the images. This soundtrack further deepens the sensation of immersion.

However, I guess that ultimately, my main focus at the moment is to find gallery representation, to have my work seen.

I feel that now and with this current work, more than ever, I am looking to interact directly with an audience and to feel some kind of connection of a shared experience.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography & Anthropology: Gloria Oyarzabal, “USUS FRUCTUS ABUSUS”May 3rd, 2024

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024