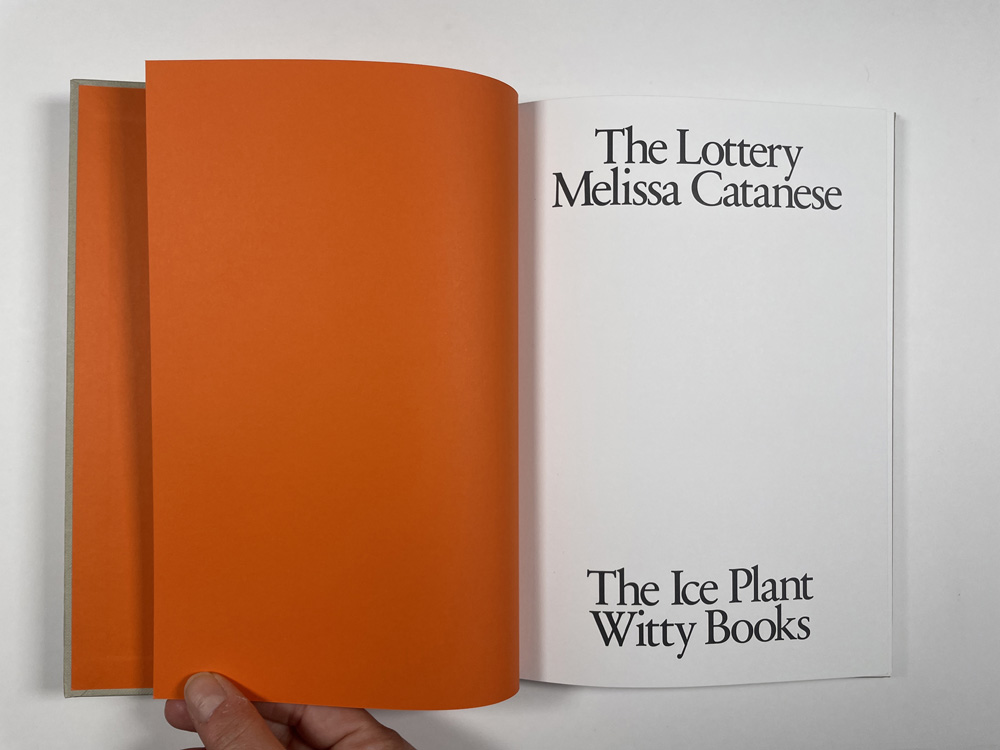

Melissa Catanese : The Lottery

Melissa Catanese’s latest book The Lottery, co-published by The Ice Plant and Witty Books, could be described as a photographic curation project, a masterful sequence of found and made images. That description would be technically true but would not prepare the viewer for the loose fictional narrative that seems to churn on both frenetic tension and vague unease. By intuitively combining her own contemporary photographs with anonymous vernacular photos, press images, and NASA archival imagery, Catanese invokes themes of mob mentality and tribalism while also exploring the cosmic uncertainties of our present reality. These themes are reminiscent of Shirley Jackson’s short story, “The Lottery,” from which the artist borrowed the title. I remember being deeply affected by that story as a middle schooler, a brutal introduction to the destructive rituals of humanity. I was eager to talk with Melissa about her photobook and the fiction that feels a little too close-to-home in our modern world.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Melissa Catanese.

TLC: My kid is reading Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery for 8th grade summer reading. I remember reading it in middle school, myself. It seems to be a dark literary rite of passage, preparing us for the sins of society. What is your personal history with this text? How did it come to be a source of inspiration for this work?

MC: Same as you, I read it in junior high. I don’t think I was intellectually mature enough to really understand the violence of it at the time, but it had such an impact on me, leaving a residue that never left. I was thinking about it when I started this project just after the presidential election in 2016. I felt like it embodied the rise of tribalism and nationalism, a kind of mob mentality and false populism. The timeless themes in the short story became metaphorical pillars in my own book. I started collecting photographs of crowds, for example.

TLC: You had written about the “diffused accountability of the mob”. Sums it up so well.

MC: Yes, it’s almost like troll culture online where you are hiding behind a screen. I feel like that happens with mobs. It becomes more anonymous, a collective pile-on rather than individual and personal accountability.

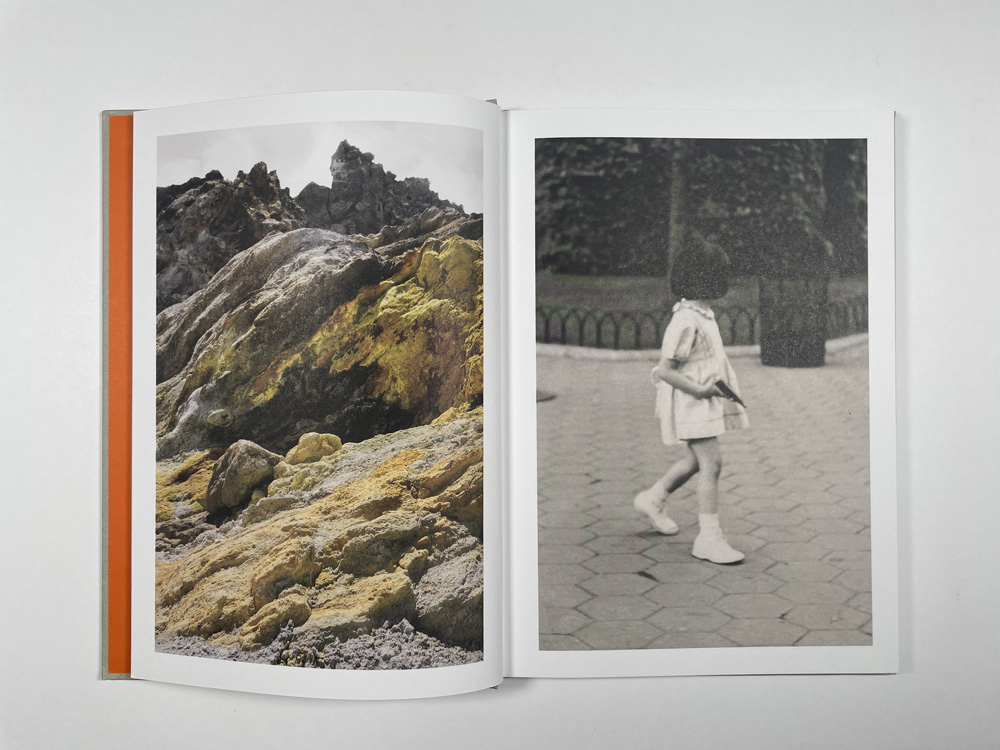

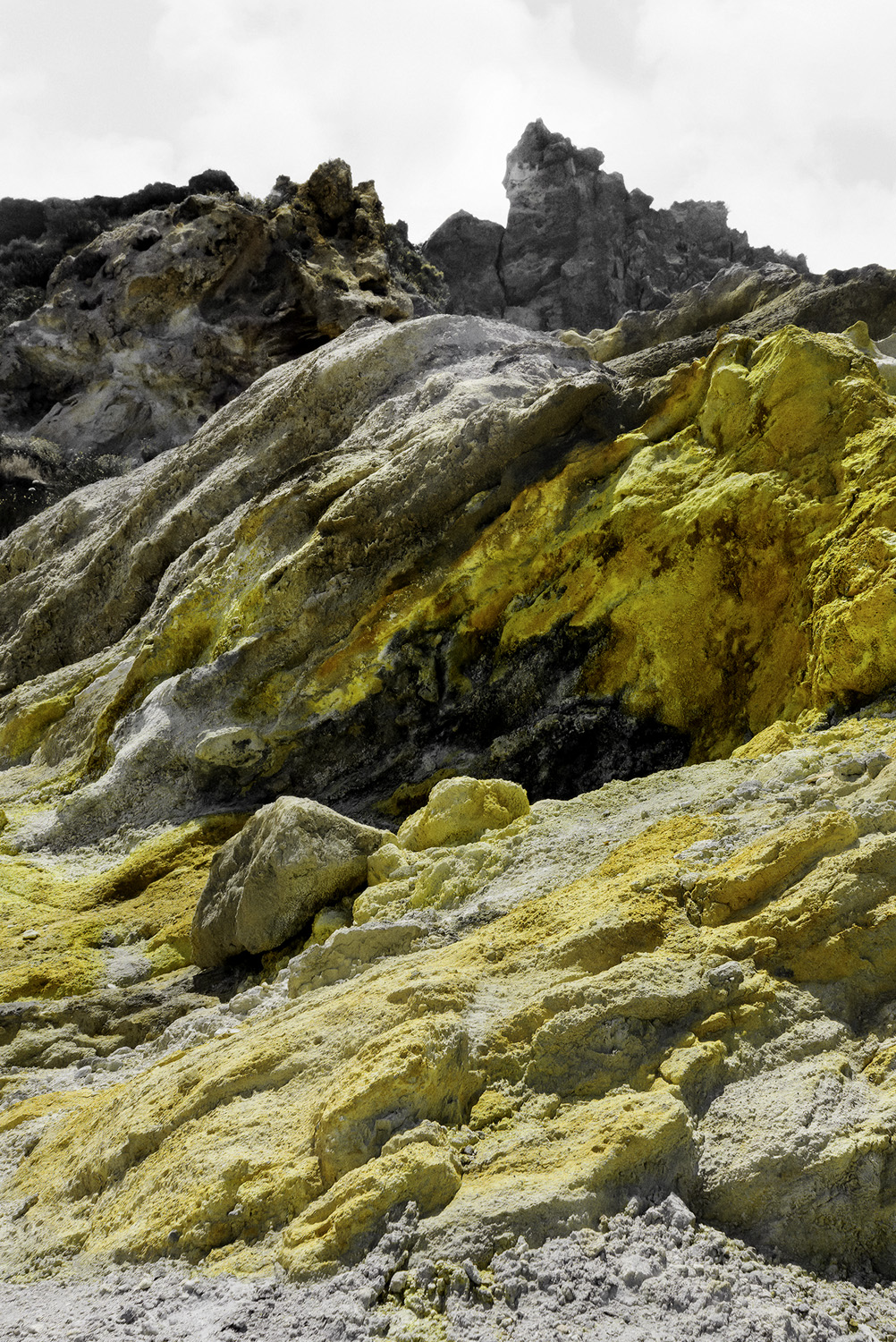

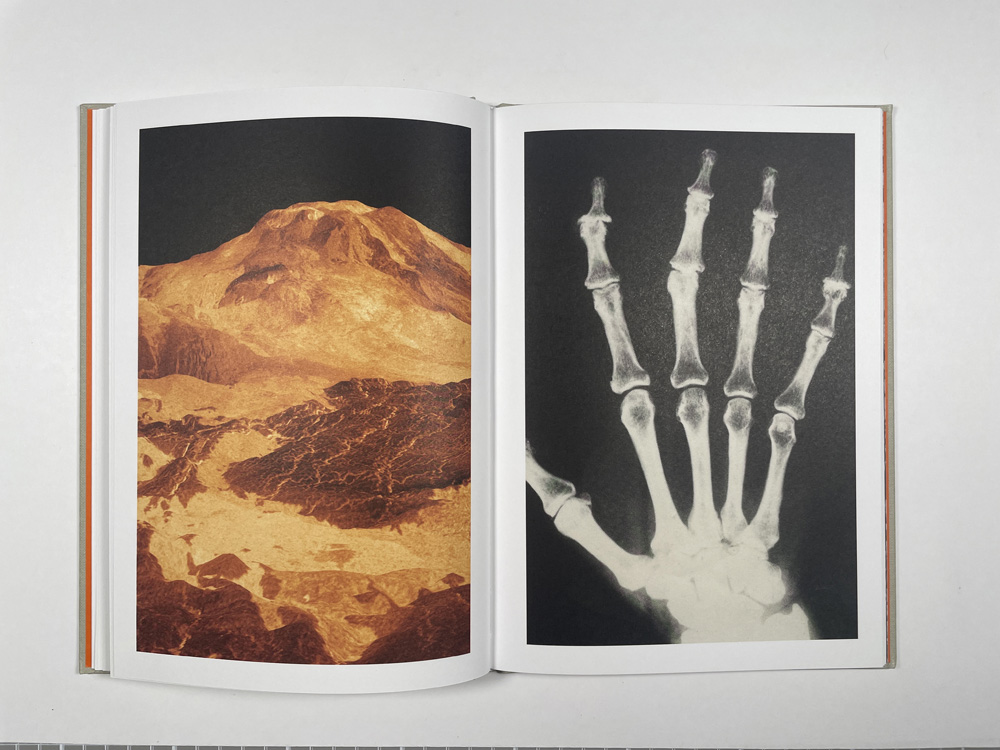

TLC: The opening images of your book are of a rock formation on one side and a young girl with a gun on the other. I am reading the geological time scale of our ever morphing planet paired with the shorter but no less violent evolution of humanity. This image of the sweet innocent child marred by the destructive tools of society is haunting. Are you taking a side on the nature vs nurture debate?

MC: I feel like that image is so striking. It speaks to the capacity for violence, but also specifically violence as a result of American attitudes towards guns. The ambiguity, the way that her head is turned, she’s looking away. It reminds me of Diane Arbus’ picture of the boy with the hand grenade and the anxiety that image brings. With this spread, there is this tension between the collective psyche of the moment and also the more glacial and extended violence of nature. The geological stratosphere and the human space.

TLC: The spread is also an example of your technique of mixing archival images with your own photographs. I understand you collected images from NASA as well as the Peter J Cohen collection. Can you describe your experience working with these collections? How did you know where to start?

MC: Peter’s collection is housed in a tiny Greenwich Village apartment that’s full of boxes of photographs. I used to work for him, helping to archive. The process was not a strict library science, but more of a subjective style of organization. Boxes of snapshots, bought from flea markets or ebay, were sorted into baseball card holders by themes. It was actually really hard to decide which bin to sort things in when you consider the multiplicity of meanings an image can hold. It was a kind of ground zero of working with images that are divorced from their context. As I sorted, I would pull images aside to scan for my own archive. I had a good 2,000 images by the end. For me they all had some sort of untapped potential for reimagining.

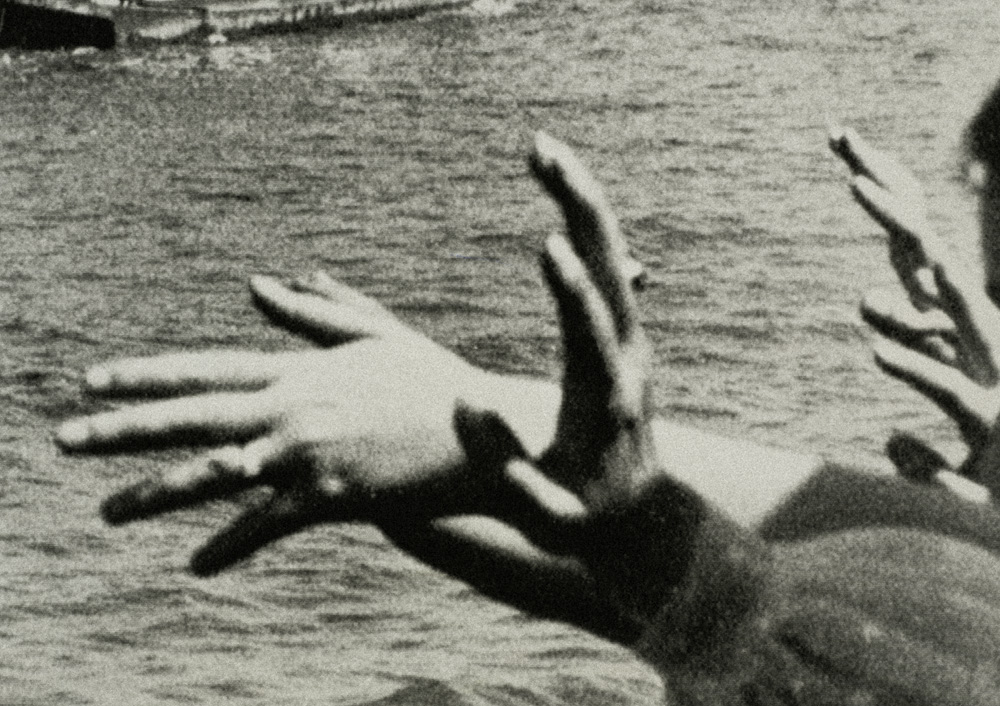

TLC: Yes, without context of the circumstances or personal experience of making the photo, you are free to see the content of the image without those strings attached. Maybe that makes it easier to see archetype and metaphor, to build narrative. Take the swimmers, for example. Are they swimming or drowning? In one image the swimmer could be floating leisurely or dead.

MC: Or resurrecting.

TLC: Exactly! A water crucifixion.

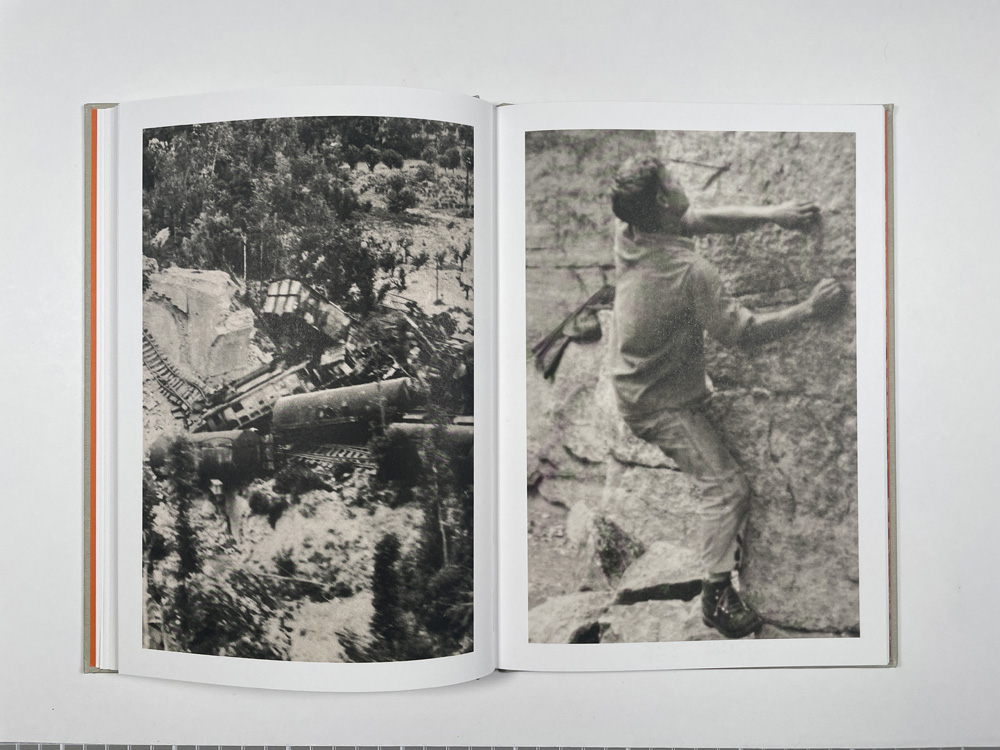

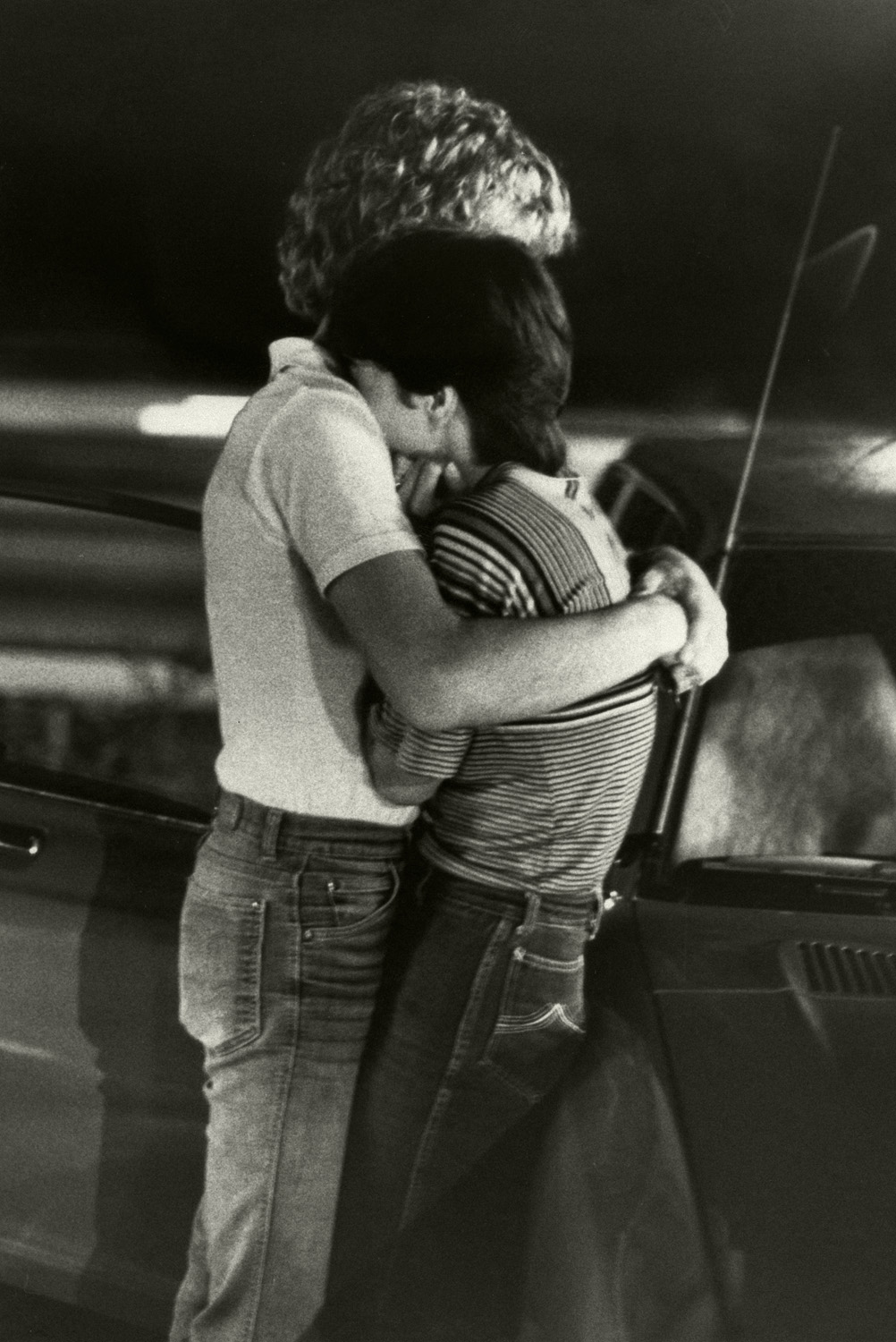

TLC: There are also many images of people touching, even embracing, yet I can’t help feeling there is little comfort. There’s one with the young men that are on this rock edge and they’re holding each other’s hands and yet it is not clear to me that one is helping the other or going to push him off this cliff. Like this could go either way.

MC: There’s an insincerity to some of them that is a little troubling or disconnective. There are other climbers too, mostly men, images of clamoring, clawing, and then figures in conflict, wrestling. But yes, also embraces. There is a press image of a woman whose son had just drowned. We’ve all experienced an overwhelming amount of collective grief and loss over the years with the pandemic, with the political turmoil, not to mention the ecological disaster that we find ourselves in. There’s trauma everywhere.

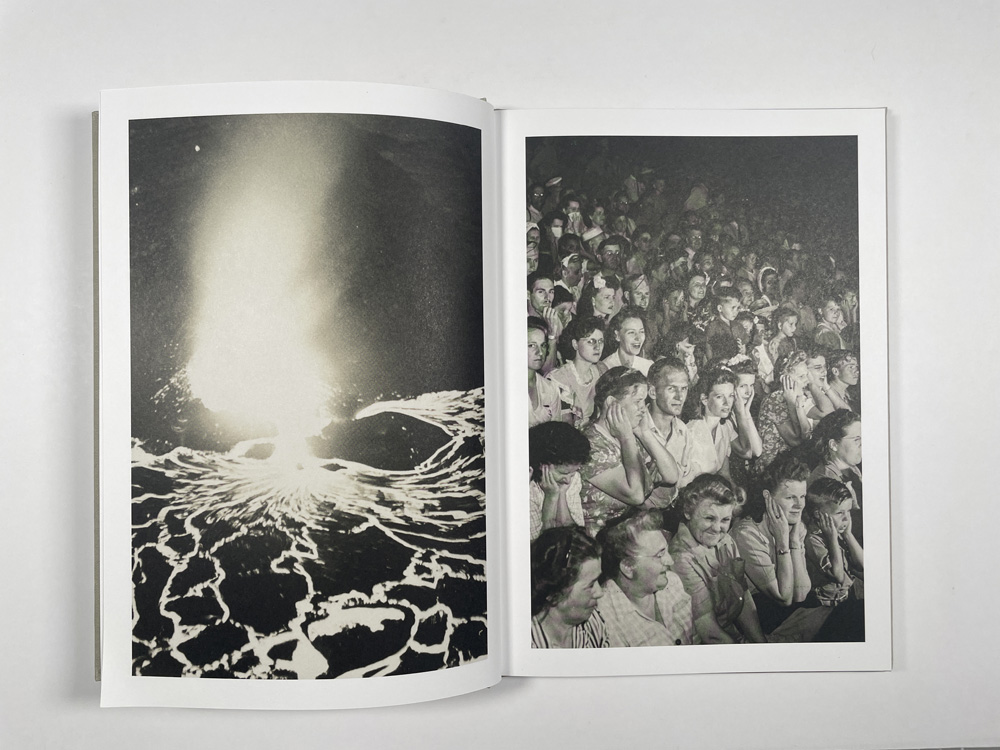

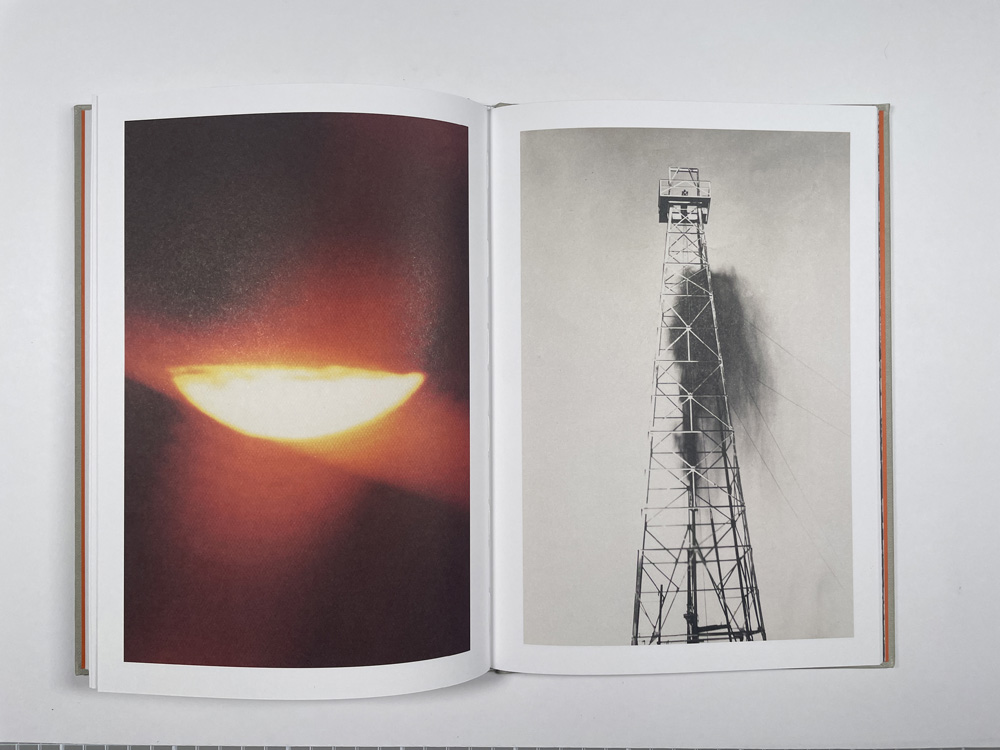

TLC: Indeed there is. And I think we all feel it. There is a low grade anxiety that periodically peaks with these political, cultural, and ecological events. It’s hard not to get doomsday-y. This theme seems to play out in your color palette. Most of the book consists of B&W or muted color imagery and every so often there is a shock of fiery orange or red, a seemingly searing threat of destruction. Can you talk about this editing choice?

MC: These bright red images, for me, feel nuclear, they hint at annihilation. I was born in 1979, the Cold War was a prominent thing. There was so much mixed messaging. Nuclear decimation and yet “the future’s so bright, you gotta wear shades”. Popular culture, movies, and music embodied this booming individualism with this underlying threat of destruction. In the book, I play with that oscillation with color.

TLC: You describe your previous book with Ice Plant, Dive Dark Dream Slow, as the “sleepwalking cousin” of the insomniatic, The Lottery. Was that a conscious direction change or was it more emergent as you went along?

MC: The latter for sure. They could be seen as companion books with a lot of connections that can be made visually and thematically. But there’s a kind of malaise in Dive Dark Dream Slow that is not there in The Lottery. The sequence in Dive Dark feels more lyrical. In a way, The Lottery is anti-lyrical. It’s dissonant and unrelenting.

TLC: Much less white space.

MC: Much less. Every page has an image and every image is pretty much taking up the whole page. It’s continually coming at us. And in the end you are immersed in this full bleed section. No white space at all.

TLC: Can you talk about the similarities and differences in your edit and sequencing for the exhibition versus the book? How does one format inform the other for you? Do you have a preference?

MC: For me, the book feels like my most natural place to work. When I’m sequencing images across pages, I feel like that’s where I’m really orchestrating and expressing what I feel like is the full potential of the work. But that being said, I like the challenge of working with a wall and to experiment with the materiality of the images themselves. There are a lot of opportunities for exploring process and form. I had an exhibition with Lightwork last year that gave me a lot of space to play with installation.

The Lottery is available for sale from The Ice Plant in the US as well as from Witty Books in Europe. The hardcover book is also available in a special edition with accompanying portfolio of risograph prints.

Melissa Catanese (b. 1979, Cleveland) combines her own photographs with archival images into a fluid, sensorial experience that pushes the image beyond its nostalgic surface and challenges ideas of authorship, representation, consumption, and the life cycle of images. She is the author of Dive Dark Dream Slow, Dangerous Women, Hells Hollow Fallen Monarch, and Voyagers. Her work has been included in the Mulhouse Biennial of Photography, NoFound Photo Fair in Paris, and at institutions including Light Work, Pier 24 Photography in San Francisco, Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Aperture Foundation, MoMA Library and ICP Library in New York.

Follow Melissa on Instagram

The Ice Plant is a photography book publisher located in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Ice Plant on Instagram

Witty Books is a photography book publisher located in Torino, Italy.

Follow Witty Books on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026